Sisterhood and slavery: a newly discovered manuscript of the ancient orator Hyperides

Two thousand four hundred years ago, a seven-year-old girl in Athens, whose parents had died, was taken by her legal guardian to the island of Lemnos. Her sister and two brothers were left behind. Years later, she and her sister ended up in the same city. They passed each other in the street, and again at a temple, but didn’t recognise each other. Eventually, one of her brothers took the guardian to court. The allegations probably concerned the children’s inheritance. One of the brother’s friends, speaking in support of his case, told the story of their childhood.

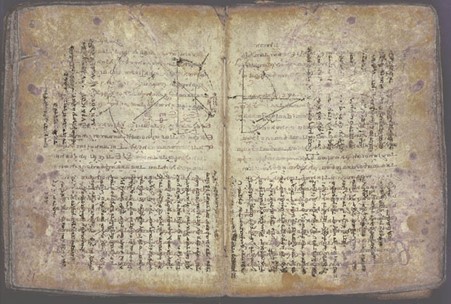

A small part of the prosecution speech, lost for two millennia, was recently rediscovered hidden beneath another text. New analysis of light waves applied to a text written on parchment by thirteenth-century Palestinian monks has enabled scholars to read more of some much older texts written underneath it. Beneath the monks’ writing are copies of lost works by the third-century BC mathematician Archimedes and two speeches by the fourth-century BC speechwriter Hyperides—one of which concerns these children. Most of the speech is missing, leaving us only with glimpses of the story and the argument.

Fifth- and fourth-century Athenians loved stories about sisters. Many popular tragedies from this period explore the dynamics of sisterly relationships. Meanwhile gravestones and legal speeches attest to long-lasting relationships between real sisters who lived and died in classical Athens. One older woman called Melino, who lived around the same time as the girls in the speech, arranged to be buried with her sister. She set up a gravestone inscribed with a poem in which she says that she and her sister, who were rich, valued their affection for each other as much as their wealth. For a legal speech, Hyperides’ text offers us an unusually intimate portrayal of a relationship between sisters—a relationship that never was. Separated in early childhood, the girls never had the chance to develop the kind of closeness Melino shared with her sister.

In stressing the awfulness of this separation and its consequences, the speaker makes a striking argument. He claims that love between family members is not ‘natural’ but comes about through growing up and spending time together. For that reason, he says, family members separated early in life wouldn’t love each other. Among authors of the time, this was an extreme view: Aristotle, for example, argues that love between family members is based on biology, and that parents love children as if they were parts of their own bodies.

Splitting one family member from another is so horrendous, the speaker says, that even slave-dealers and slave-traffickers (bywords for amorality, unsentimentality and unscrupulous profitmaking) sell young siblings or mothers and infants together, rather than splitting them up. Considering the evidence for ancient Greek slaving practices, this claim is misleading at best. Victorious soldiers capturing a community typically destroyed families by killing certain members (men and boys, the elderly, the very young) but may have allowed mothers to keep their babies for as long as they survived if it would make them less resistant.

What is remarkable about the claim are the assumptions behind it. The speaker apparently assumes that the jurors (Athenian juries normally numbered in the hundreds) agreed that enslaved people had meaningful relationships with their family members which ought to be respected. To us, this might sound obvious. But slavery was fundamental to Athenian society and relied on the dehumanisation of the people enslaved. Family memberships between enslaved people were not recognised or protected in law. Perhaps Athenians were not fully convinced by the logic they themselves used to justify slavery. They recognised the humanity of the people they enslaved—but enslaved them all the same.

Katherine Backler’s article SISTERHOOD, AFFECTION AND ENSLAVEMENT IN HYPERIDES’ AGAINST TIMANDRUS is free to access in The Classical Quarterly until 30 June 2023.