Introduction

The act of modifying the human body is a widespread practice, with a deep history in human cultures around the world. Modifications to soft tissue, including tattooing, present a temporal paradox as they are simultaneously permanent over the lifetime of the marked individual, yet transitory from an archaeological perspective. The scant material record of tattooing dates back at least 5300 years (Deter-Wolf et al. Reference Deter-Wolf, Robitaille, Krutak and Galliot2016), although the practice may extend much further into the human past (Renaut Reference Renaut, Krutak and Deter-Wolf2017). Pigments embedded within the canvas of human skin may serve as expressions of personal beliefs, cultural traditions and social affiliations today and ethnohistorically (e.g. Krutak Reference Krutak2007, Reference Krutak2012, Reference Krutak2014, Reference Krutak2024), but the interpretation of tattoos in prehistoric contexts necessarily remains speculative and may never reach the intricate richness of meaning with which the images and practices were originally associated.

Direct evidence of ancient tattooing is scarce and the frequency of this practice is likely underestimated, particularly in regions where organic remains are rarely preserved. Recently, a shift away from purely stylistic interpretation has occurred in the study of ancient tattoos, and a more varied methodological toolset has been established through collaborations between archaeologists, professional tattooists and indigenous practitioners (e.g. Deter-Wolf et al. Reference Deter-Wolf, Riday and Sialuk Jacobsen2022, Reference Deter-Wolf, Robitaille, Riday, Burlot and Sialuk Jacobsen2023a, Reference Deter-Wolf, Robitaille, Fromme, Gerst and Riday2024a). This merging of expertise across fields has facilitated new approaches in the investigation and interpretation of ancient tattoos, bringing us a step closer to unravelling the cultural significance and potential societal roles tattooed images played in their sociohistorical contexts.

The elaborate figural tattoos that adorn the human bodies preserved for more than two thousand years in the Altai Mountains are among the most iconic archaeological finds of Inner Asia (Brilot Reference Brilot2000; Bonora Reference Bonora2018). The Pazyryk culture, characterised by distinct horse gear, weaponry and decorative style, was part of the so-called ‘Scythian World’ (Rolle Reference Rolle1989; Yablonsky Reference Yablonsky, Davis Kimball, Murphy, Koryakova and Yablonsky2000). This umbrella term refers to the plethora of Early Iron Age pastoralist peoples across the Eurasian steppe, a vast ecoregion stretching from Northern China to Eastern Europe (Cunliffe Reference Cunliffe2019). These cultures crafted elaborate artefacts in the Scytho-Siberian animal style, which finds its reflection in the preserved body decorations that are often in the form of animal fighting scenes and fantastical composite animals (Simpson & Pankova Reference Simpson and Pankova2017; Linduff & Rubinson Reference Linduff and Rubinson2021; Pankova & Simpson Reference Pankova and Simpson2021).

Early scientific expeditions to the Altai were conducted by V. Radlov in the nineteenth century (Radlov Reference Radlov1895). Although Radlov discovered the first frozen tombs, modern archaeological knowledge of the mounded monuments with subterranean burial chambers only began to emerge with the excavations conducted by M. Gryaznov and S. Rudenko in the 1920s and 1940s (Rudenko Reference Rudenko1970). Rudenko found that the deep burial chambers were lined with log cabin-like constructions. Some of these tombs were encased within a permafrost lens, leading to the preservation of a rich assemblage of organic artefacts made from wood, leather, felt and textiles, as well as mummified human bodies. Research into the frozen tombs of the Russian Altai Mountains continued in the 1990s with excavations on the Ukok Plateau (Polosmak & Francfort Reference Polosmak and Francfort1991; Polosmak & Seifert Reference Polosmak and Seifert1996; Molodin & Polosmak Reference Molodin and Polosmak2000), and international projects have revealed frozen tombs in the Kazakh (Samashev et al. Reference Samashev, Bazarbaeva, Zhumabekova and Francfort2000) and Mongolian parts of the mountain range (Molodin et al. Reference Molodín, Parzinger, Ceveemdorz, Garkusa and Grisin2008). Research on both new and known frozen sites in the Altai and beyond has continued over the last decade (Caspari et al. Reference Caspari, Sadykov, Blochin and Hajdas2018; Konstantinov et al. Reference Konstantinov, Slyusarenko, Mylnikov, Stepanova and Vasilieva2022). Due to a warming climate and thawing permafrost, these rare monuments are now under threat of destruction (Bourgeois et al. Reference Bourgeois, De Wulf, Goossens and Gheyle2007; UNESCO 2008; Clark et al. Reference Clark, Bayarsaikhan, Ventresca Miller, Vanderwarf, Hart, Caspari and Taylor2021).

Seven tattooed individuals are preserved from the Early Iron Age of southern Siberia (ninth–second centuries BC) (see Table 1). We exclude here the mummy from the Oglakhty burial ground in the Minusinsk region, which also features tattoos but dates to a much later period in the third or fourth century AD and thus belongs to a different cultural context (Pankova Reference Pankova, Della Casa and Witt2013). Preserved tattoos were first documented in southern Siberia in the 1940s as visible marks on the body of the male from Pazyryk tomb 2 (Rudenko Reference Rudenko1970). No tattoos were visible at that time on the female buried in the same tomb, nor on the male and female individuals recovered from tomb 5 at the same site. Decades later, infrared imaging of the bodies from the Pazyryk site at the Hermitage Laboratory for Scientific and Technical Expert Evaluation led to the discovery of previously undocumented tattoos on all four individuals (Barkova & Pankova Reference Barkova and Pankova2005; Pankova Reference Pankova, Krutak and Deter-Wolf2017). Preserved Pazyryk tattoos have also been noted on the bodies of a female from tomb 1 at Ak-Alakha-3 (Polosmak Reference Polosmak1994), a young male from Verkh-Kaldzhin-2 (Polosmak Reference Polosmak2000) and an older male from Olon-Kurin-Gol-10 tomb 1 (Molodin et al. Reference Molodín, Parzinger, Ceveemdorz, Garkusa and Grisin2008). Thus, well-preserved human remains from Pazyryk cultural contexts generally exhibit tattoos. Given the rarity of the preservation conditions under which tattoos can be identified, it can be assumed that tattooing was a widespread practice across social strata at this time and in this region.

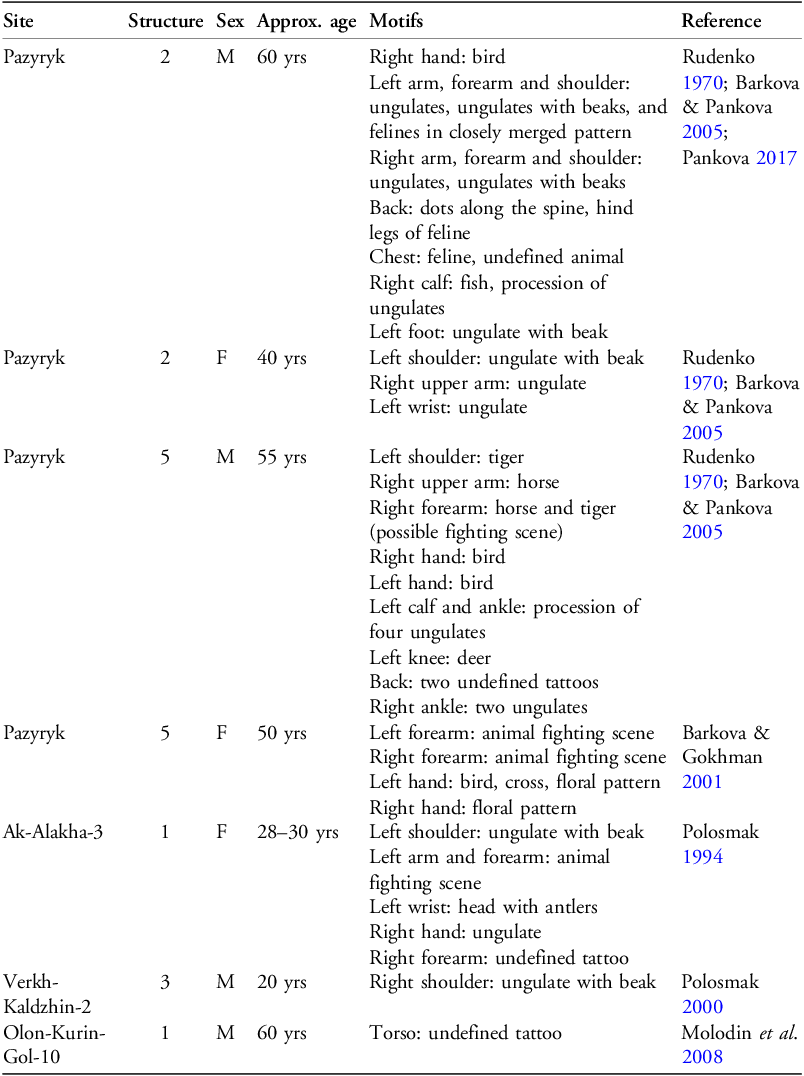

Table 1. Mummified remains from the Early Iron Age Altai Mountains.

Detailed studies of Pazyryk tattooing techniques and evaluation of the role of individual tattoo artists have not previously been possible, in part due to a lack of data from high-resolution images. The Pazyryk tattoos are typically published as monochrome drawings, obscuring fine details and leaving doubts as to how the original forms may have been (re)interpreted during the conversion into drawings. With newly available sub-millimetre resolution near-infrared digital photography and three-dimensional derivatives, we reinvestigate the tattoos of the female individual from Pazyryk tomb 5 and compare the results with new experimental data and archaeological findings.

Methods

A three-dimensional digitisation of the female mummy from Pazyryk tomb 5 was carried out at the State Hermitage Museum using digital photogrammetry, including data in both the visible and near-infrared range. A modified Nikon D3100 camera with a dismantled hot mirror was used for near-infrared photography. Floodlights with a wavelength of 850nm were installed around the mummy during the shoot. The Agisoft Metashape software was used for photogrammetric processing, resulting in a 3D polygonal model of the mummy with two textures (Figure 1). The model is publicly accessible on Sketchfab, courtesy of the Laboratory for Interdisciplinary Research in Archaeology (‘Artefact’) of the National Research Tomsk State University (https://skfb.ly/oVoEt).

Figure 1. Photogrammetrically created 3D model of the female mummy from Pazyryk tomb 5, showing: A) texture derived from visible-spectrum photographs; and B) texture derived from near-infrared photography (figure by M. Vavulin).

The new digital imagery was compared with data from a recent experimental study examining the physical characteristics of tattoos created using different pre-electric techniques and tools (Deter-Wolf et al. Reference Deter-Wolf, Riday and Sialuk Jacobsen2022). In that investigation, a series of tattooing tools were created based on archaeological, historical and ethnohistorical data and used by one researcher (D. Riday) to tattoo their own leg with eight identical patterns. Each tattoo was created using a separate tool and/or technique and included both lines and filled areas. By monitoring and documenting these tattoos as they healed, investigators were able to distinguish specific physical differences between the marks, correlating to tool type and/or technique. The results of this experiment have subsequently been applied to the evaluation of tattooing techniques used on the Chalcolithic Iceman from the Tyrolean Alps, and on mummified bodies from the Andes in South America (Deter-Wolf et al. Reference Deter-Wolf, Robitaille, Riday, Burlot and Sialuk Jacobsen2023a, Reference Deter-Wolf, Robitaille, Fromme, Gerst and Riday2024a & Reference Deter-Wolf, Auten, Robitaille, Riday, Manni and d’Erricob).

In a recent survey of global patterns of pre-electric tattooing technologies, Robitaille and colleagues (Reference Robitaille, Deter-Wolf, Sialuk Jacobsen, Manni and d’Errico2024) describe a diversity of techniques used to insert pigments beneath human skin. Those are classified within two principal categories: puncture tattooing and tattooing by incision. Puncture tattooing takes place when the skin is pierced with a pointed implement that conveys pigment into the epidermis. Specific technologies within this category include both hafted and unhafted implements featuring one or more points. When applied directly to the skin by hand, these tools fall into the subcategory of ‘hand poking’. This technique is the most prevalent pre-electric tattooing method and appears historically on all continents except Australia and Antarctica (Robitaille et al. Reference Robitaille, Deter-Wolf, Sialuk Jacobsen, Manni and d’Errico2024). A separate subcategory of puncture tattooing involves tools with one or more points that are hafted at an angle to the handle, which are struck into the skin with a secondary implement. This technique, today known as ‘hand tapping’, appears historically limited to Oceania, and portions of insular Southeast Asia, mainland Southeast Asia and the Himalayan slope (Robitaille Reference Robitaille, Gates St-Pierre and Walker2007; Robitaille et al. Reference Robitaille, Deter-Wolf, Sialuk Jacobsen, Manni and d’Errico2024). The final subcategory of puncture tattooing is subdermal tattooing, in which an eyed needle or awl is pushed horizontally through pinched skin to create adjacent wounds. Pigment is introduced into the opened channel on pulled thread or sinew, or on the tip of a second implement (Deter-Wolf et al. Reference Deter-Wolf, Riday and Sialuk Jacobsen2022). Subdermal tattooing appears primarily among circumpolar cultures, as well as along North America’s Northwest coast, in Brazil and southern South America (Robitaille et al. Reference Robitaille, Deter-Wolf, Sialuk Jacobsen, Manni and d’Errico2024). Tattooing by incision involves slicing the skin with a sharp implement such as a metal blade or lithic tool. Pigment is then introduced to the wound by rubbing in from the surface. Incision tattooing is historically documented on all continents except Antarctica and Australia, but as a global practice is much rarer than puncture tattooing (Robitaille et al. Reference Robitaille, Deter-Wolf, Sialuk Jacobsen, Manni and d’Errico2024).

Results

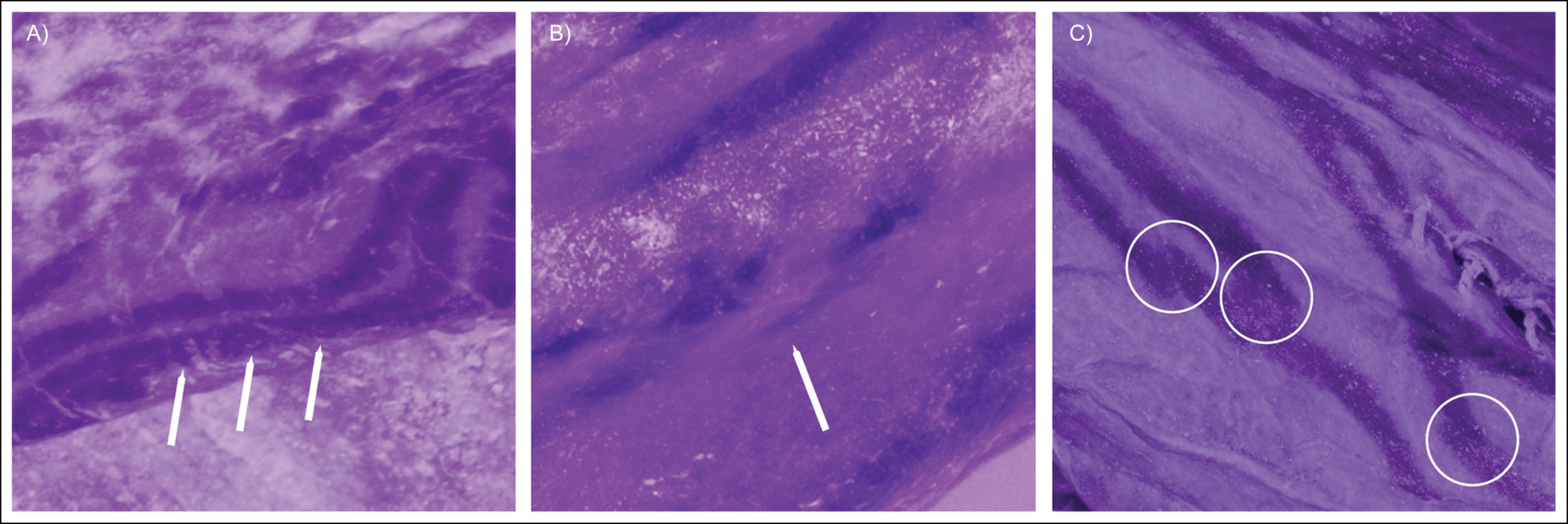

Analysis of the near-infrared photographs reveals that tattooed lines on the forearms of the female individual from tomb 5 are generally of uniform thickness. Irregular line margins are likely the result of postmortem taphonomic processes affecting the skin surface. There is no evidence of fine stippling or extraneous small marks along the edges such as would result from using a single-point tattooing tool to gradually build up line thickness. Rather, the regular margins and density found on most figure outlines suggests those marks were created using a multi-point tool with a total apical diameter equal to the line thickness (Figure 2A). However, our analysis suggests that the Pazyryk tattooist employed more than one tool in creating the marks. Although most of the outlines and dotwork in the forearm tattoos is relatively uniform in size, pointed designs such as those found at the tips of the ungulate’s antlers are much narrower (Figures 2B, 3 & 4). These elements indicate that the design was finished with a separate, finer tool, likely consisting of a single point. A similar small tool was also used to tattoo motifs on the back of the hands (Figure 5). Visible overlapping of line ends in some locations (Figure 2C) shows where the tattooist began and ended individual efforts, perhaps corresponding with a change in position or the need to reapply pigment to the tool tip. There is no physical evidence that Pazyryk tattoos were created by either subdermal techniques or through incision (cf. Deter-Wolf et al. Reference Deter-Wolf, Riday and Sialuk Jacobsen2022, see also Deter-Wolf et al. Reference Deter-Wolf, Riday and Sialuk Jacobsen2023b).

Figure 2. Details of the technical execution of the tattoos: A) roughly equal line widths indicating the use of a multi-point tool; B) thin-line finish indicating the use of a single-point tool; C) overlapping lines indicating pauses in the workflow (figure by G. Caspari & M. Vavulin).

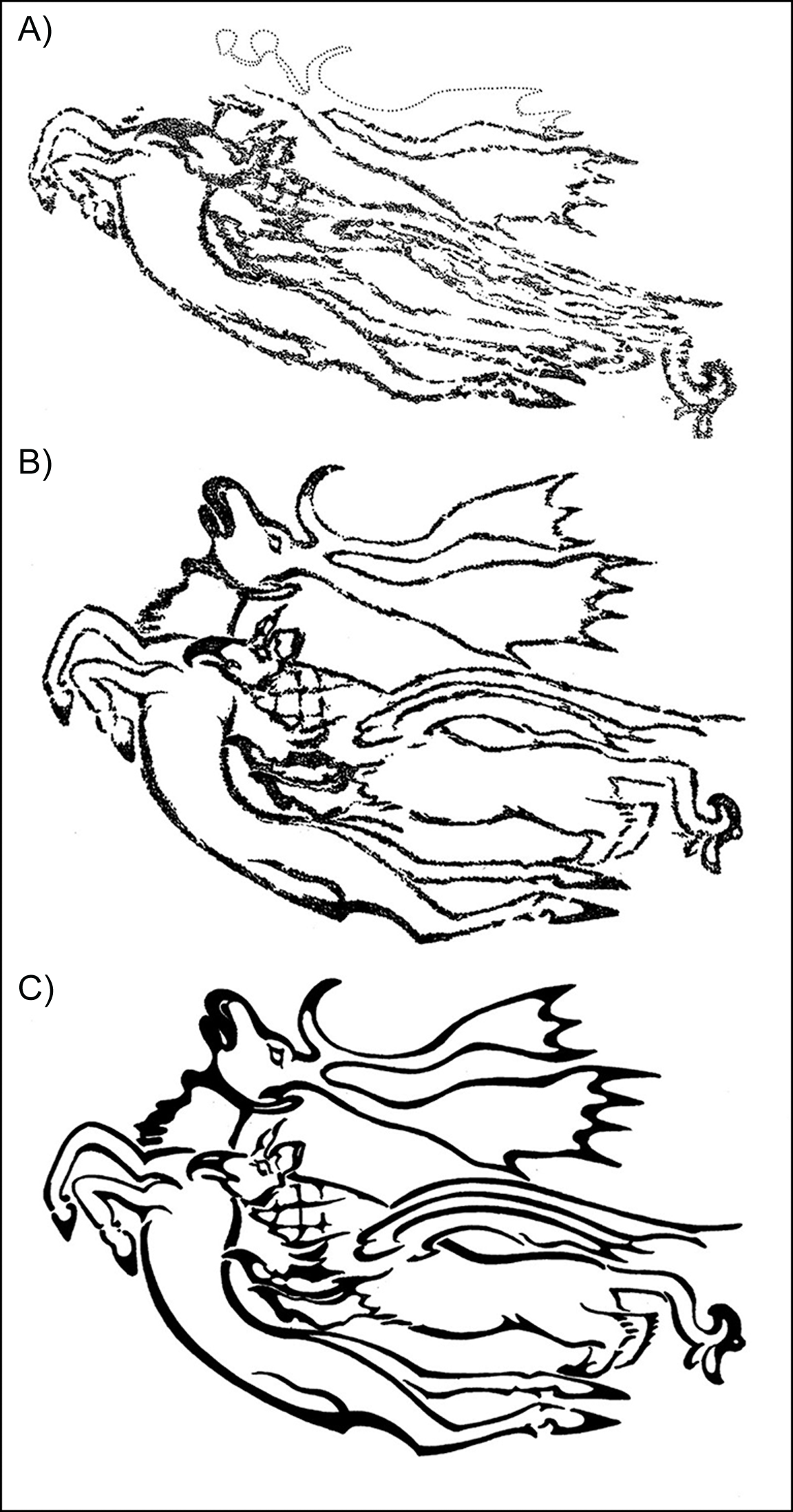

Figure 3. Left forearm tattoo: A) current state; B) deskewed, evening out skin folds and compensating for the desiccation process, and with the ungulate head recreated based on Pazyryk animal fighting scenes; C) idealised artistic rendering (illustrations by D. Riday).

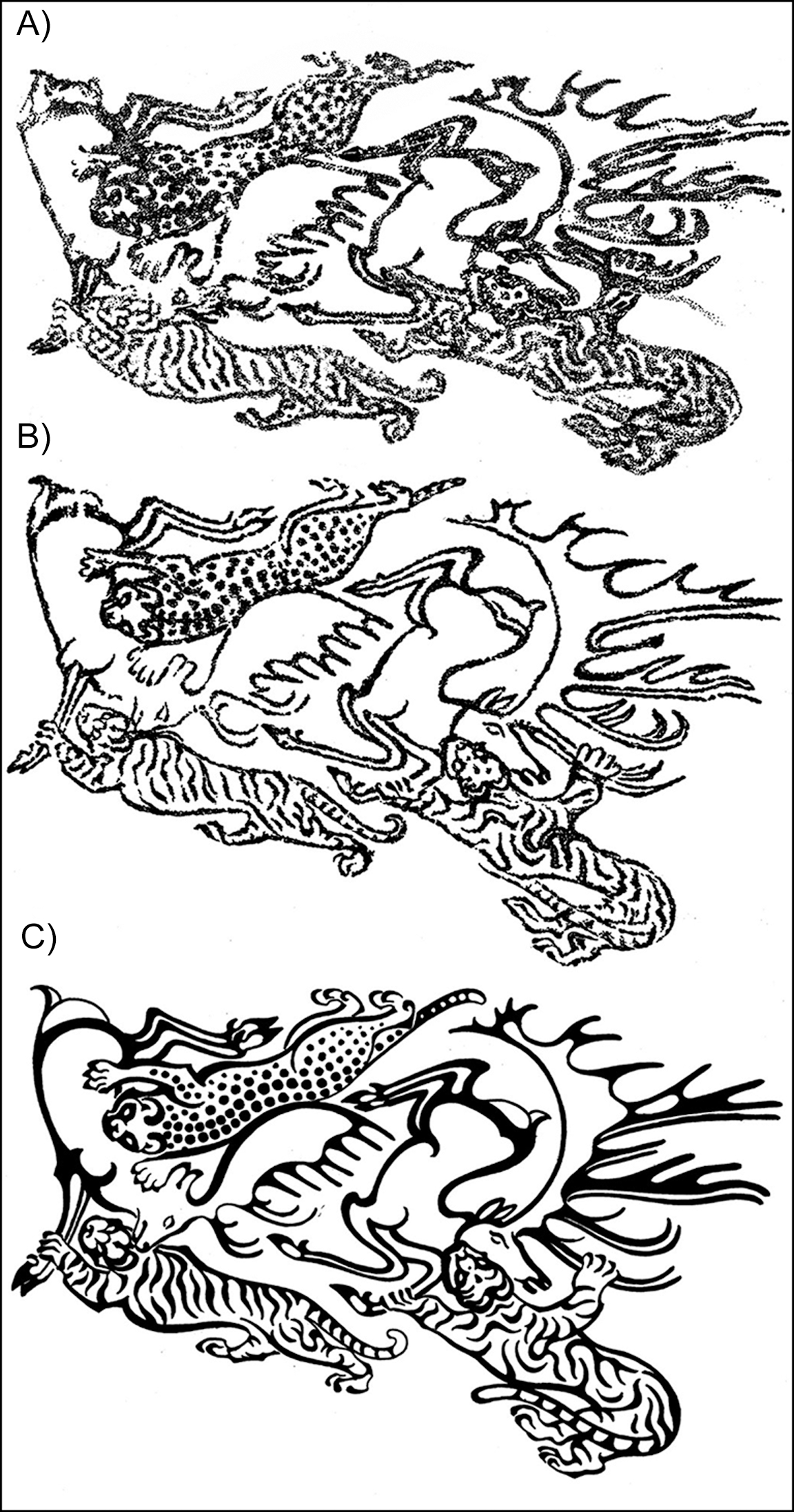

Figure 4. Right forearm tattoo (left side oriented toward the wrist): A) current state; B) deskewed, evening out skin folds and compensating for the desiccation process; C) idealised artistic rendering (illustrations by D. Riday).

Figure 5. Tattoos placed on the hands; the bird, cross, and fish-like ornament are on the left hand, the floral ornament is on the right hand: A) current state; B) deskewed, evening out skin folds and compensating for the desiccation process; C) idealised artistic rendering (illustrations by D. Riday).

Discussion

The tattoos on the body of the female individual from Pazyryk tomb 5 broadly cluster into four regions: left hand, left forearm, right hand and right forearm (Figures 3, 4 & 5). No tattoos are present in places that are otherwise typical for most of the Pazyryk mummies, including the shoulder areas (Barkova & Pankova Reference Barkova and Pankova2005). While the images on the hands are mostly simple designs, the most elaborate of which is a rooster on the left thumb (Figure 5), the forearms display some of the most complex Pazyryk tattoos currently identified.

Stylistically, the tattoos on both forearms exhibit many of the same characteristics. However, the right forearm (Figure 4) includes key elements that set it apart; a finer attention to detail and a greater array of visual techniques in the right-forearm tattoos compared with those on the left forearm (Figure 3), suggest a more experienced and skilful tattooist. The right-forearm tattoo likely required at least two sessions to complete, beginning with the ungulate positioned at the wrist. This clever placement utilises the contours of the wrist to enhance the ungulate’s form, allowing the tattoo to flow across the arm. This decision showcases the artist’s expertise while also establishing the central feline as the main focal point of the design. The use of focal points and directional flow is executed on the right forearm where the vertical alignment of the abdomen and antlers of the two ungulates establish the axis of the composition. The tattooist skilfully applied and expanded upon rules of perspective, depicting the heads of the leopard and upper tiger turned to face the viewer. This frontal presentation is rare in classical Pazyryk tattooing and uncommon in traditional Scythian animal-style art, indicating a departure from convention. The other tattoos, however, adhere to the overall Pazyryk variety of animal style.

The right-forearm tattoo also features techniques that are challenging from the tattooist’s perspective. The use of clear parallel lines with negative space, along with the finer details in the hooves, stripes, paws and antler tips, likely required at least two different tool arrangements. The linework is clear and consistent, with nearly double the amount of outlining present on the left forearm. Achieving such crisp and uniform results, especially with hand-poked methods, would be a challenge even for contemporary tattooists using modern equipment. The hypothesis that the right-forearm tattoo was created over at least two sessions is supported by the lack of interaction between the first set of animals (the lower ungulate and two felines) and the subsequent addition of the upper ungulate and the tiger. These latter animals appear to be fitted into the open space left by the first set of animals, suggesting a phased approach to the tattooing process. The complexity of the design and the precision required further support the notion of a multi-session creation.

The tattoo on the left forearm demonstrates less fine detail compared with the more sophisticated design on the right forearm (Figure 3). This difference suggests that the artist responsible for the left forearm tattoo may have either lacked the time or skill to fully develop the composition. Unlike the right-forearm composition, which is carefully placed to flow with the natural forms of the human body, the design on the left does not exhibit such intentional placement. The left-forearm tattoo avoids more mobile parts of the body, choosing instead simpler areas that pose less risk in terms of visibility. The head of the ungulate wraps around to the inside of the forearm, requiring the wearer to turn their arm outward to fully display the motif. The left-forearm tattoo also does not utilise the engagement with perspective seen on the right arm. Both front legs of the stag protrude from the near side of the animal, ignoring the rules of perspective that would otherwise give depth to the depiction. Anatomical accuracy of the limbs and hooves in the left-forearm tattoo are further lacking when compared to the deer on the right forearm, and the limbs of both creatures on the left are oversimplified in comparison. Taken as a whole, this evidence suggests that the left forearm tattoo was created by an artist with less experience or skill.

With the high resolution afforded by near-infrared imaging, the sharp contrast is apparent between the lack of fine detail, intentional placement, perspective and anatomical accuracy in the tattoo applied to the left forearm and the more advanced visual techniques observed on the right forearm of the female from Pazyryk tomb 5. This highlights the varied skill levels among ancient tattooists and allows us to posit a hypothesis that these images were made by two different people or perhaps represent earlier and later stages of experience in one artist’s development. The qualitative differences between these two compositions not visible in earlier black-and-white reconstructions, show the importance of gathering high-resolution near-infrared data for the study of archaeological tattoos.

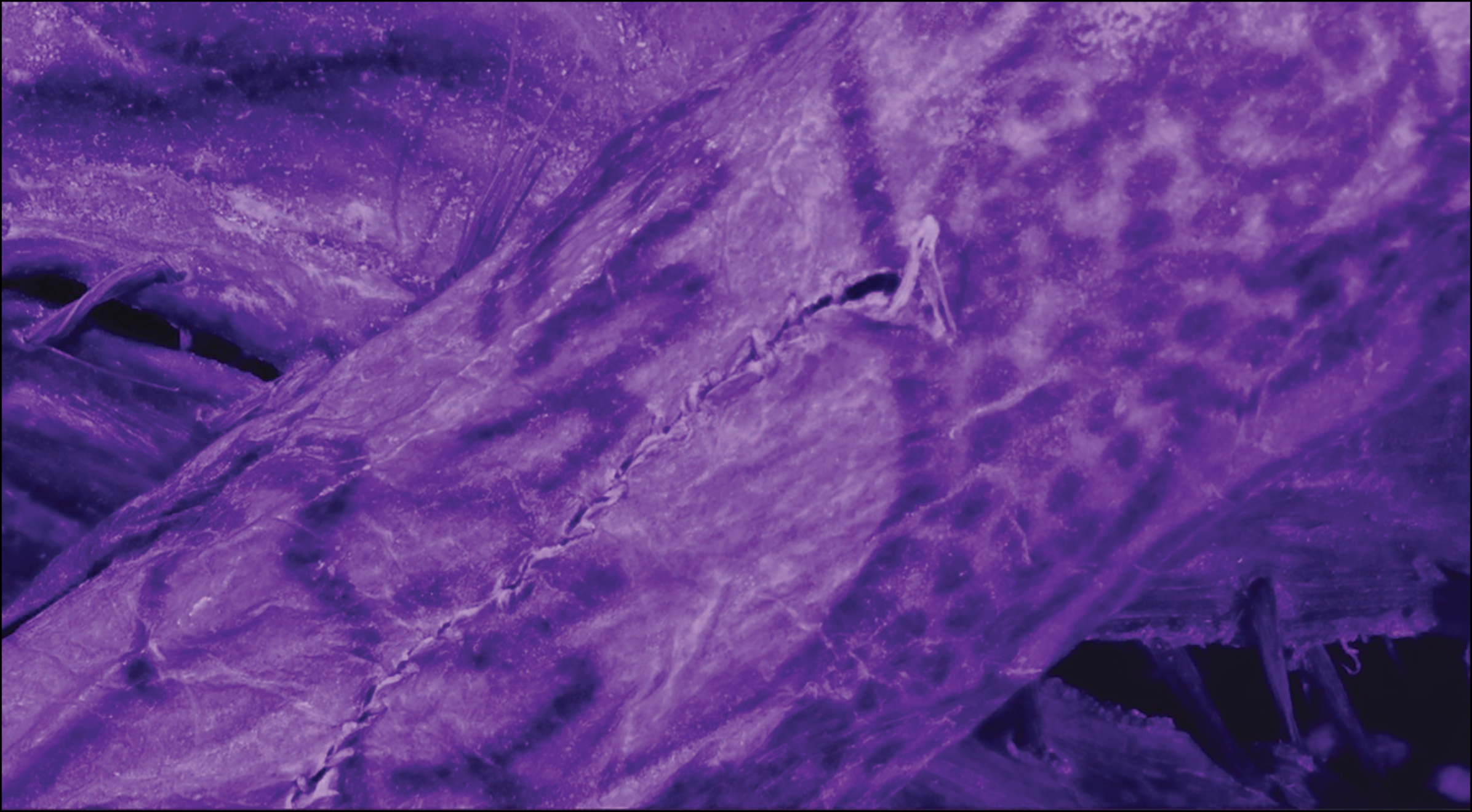

The new imagery also allows a first assessment of the relationship between Pazyryk tattoos and the sutured skin cuts associated with preparing the body for burial (Slepchenko et al. Reference Slepchenko, Shin and Bianucci2021). Those post-mortem cuts run across the forearm tattoos of the female from Pazyryk tomb 5 (Figure 6). The global cross-cultural sample of indigenous and historic tattooing traditions includes multiple examples of belief systems wherein the presence of intact tattoos was critical in the spiritual transition to the afterlife (e.g. Hose & Shelford Reference Hose and Shelford1906; Forde Reference Forde1931; Gifford Reference Gifford1933; Drucker Reference Drucker1941; Sachdeva & Rani Reference Sachdeva and Rani2023). The apparent disregard for preserving tattoo designs during Pazyryk burial preparation suggests that the social or spiritual function of the marks ended with the death of the individual. We thus posit that the tattoos of the Pazyryk people were intricately tied to the world of the living and had limited relevance in a burial context. Intentional destruction of some of the images is possible, though unlikely.

Figure 6. Post-mortem sutured skin cuts through the images indicate that the tattoos did not play a specific role in funerary ritual and possibly lost their meaning when the individual died (figure by G. Caspari & M. Vavulin).

Direct analyses of skin from Ak-Alakha-3 and Oglakhty have revealed the use of carbonised plant material or soot as tattoo pigment (Polosmak Reference Polosmak2001; Pankova Reference Pankova, Della Casa and Witt2013). The use of a carbon base for pigment matches trends in global historical tattooing practices, wherein black ink was derived predominantly from charcoal, ash or soot (Krutak Reference Krutak2007). A similar pigment could be imagined for the black tattoos of Pazyryk tomb 5. The tools used by Pazyryk tattoo artists, however, are more difficult to identify. In the artefact assemblage from the fourth century BC Sarmatian site of Filippovka 1, Yablonsky (Reference Yablonsky2015, Reference Yablonsky, Krutak and Deter-Wolf2017) identified a set of six gold needles as tattooing tools. Those mortuary inclusions were associated with artefacts used for pigment mixing, storage and application. Although these tools have not been subject to direct microwear analysis, the Filippovka 1 burial assemblage meets associative criteria for identifying potential tattooing implements (Deter-Wolf Reference Deter-Wolf2013; Deter-Wolf & Gillreath-Brown Reference Deter-Wolf, Gillreath-Brown, Manni and d’Errico2023). Unfortunately, the environmental conditions in the Urals preclude the possibility of mummies surviving, so it is not currently known whether tattooing was practised in the region, and the identification of the Filippovka artefacts as tattooing tools remains speculative (Maresca Reference Maresca2019).

Three of the gold tools from Filippovka 1 have twisted handles, while the other three have eyed ends, leading to suggested variations in function. Initially Yablonsky (Reference Yablonsky2015) hypothesised that the tools with twisted handles were used to cut the skin, while those with eyed ends were used for injecting dye and suturing cuts. In subsequent analysis, it was suggested that these artefacts were used for direct puncture or subdermal tattooing, depending on tool morphology (Yablonsky Reference Yablonsky, Krutak and Deter-Wolf2017). The suggestion of subdermal tattooing draws entirely on Rudenko (Reference Rudenko1970: 112), who earlier proposed that Pazyryk tattoos were created using a soot-based pigment inserted beneath the skin by “stitching or pricking”. Direct examination of the subcutaneous distribution of pigment in tattoos on the male from Pazyryk tomb 2 led Rudenko to subsequently conclude that the images were likely created by puncture rather than subdermal methods. X-ray spectral microprobe analysis of the Ak-Alakha-3 mummy revealed dotted areas about 20μm in diameter which also suggest puncture techniques (Polosmak Reference Polosmak2001). No physical or historical data to date supports the presence of subdermal or incision tattooing in the Iron Age Altai.

The single-point tools from Filippovka 1 or similar artefacts might have been used for hand poking thin lines, but our analysis demonstrates that Pazyryk tattoos were likely made with an array of different implements (see also Deter-Wolf et al. Reference Deter-Wolf, Riday and Sialuk Jacobsen2023b), including a multi-point tool, which is (to our knowledge) still missing from the archaeological record of the region. We did not find any evidence for the use of subdermal or incision tattooing techniques.

Our approach demonstrates that the documentation of tattoos on mummified bodies using high-resolution near-infrared photography and photogrammetry contributes crucial information regarding the creation of those marks and their original composition. Aspects, including the uniformity of lines, saturation of pigment, irregularities at the margins of individual features, and taphonomic impacts, cannot be recognised in the black-and-white recreation drawings that have traditionally been the format of choice for presenting preserved tattoos from the archaeological record. As our study reveals, the information loss that occurs in the presentation of these flattened, high-contrast drawings can oversimplify or misrepresent the actual tattoo motifs, thereby limiting or omitting informed discussion as to methods of application and potentially associated tools from the archaeological record.

Conclusion

The use of high-resolution near-infrared images and photogrammetry to examine tattoos from the Iron Age Altai offers substantial advantages over the black-and-white drawings traditionally used for documentation and dissemination. In providing a more accurate rendering, near-infrared imaging further reveals tattooing methods, helping to identify differences in authorship and skill and taphonomic changes to the tattoos. The specialisation revealed in the tattooing methods and technique highlights the sophistication of Pazyryk tattooing practices. Without the information offered by near-infrared photography, subtle details such as overlaps at the end of lines where the tattooist needed to adjust position or reapply pigment to the tools would be invisible, and the associated insights into workflow would remain hidden. Ultimately, this approach to documentation allows differentiation of tattooing methods and tools, leading to a more accurate understanding of the prehistory of this important cultural practice. Our findings therefore expand our understanding of these images beyond their treatment as an expression of a large-scale art historical phenomenon.

The absence of overlapping images or compositions in the corpus of preserved examples suggests that the construction of tattooed bodies in Pazyryk culture was approached in a structured and deliberate manner throughout an individual’s lifetime. This implies both planning and intentionality in tattoo placement and design. The confirmed use of multiple tools and stylistic variations on a single body also reveals that tattooing in Pazyryk culture was associated with a high degree of craft specialisation and was probably performed by multiple individuals. In this regard, the collaboration between modern tattooists and archaeological researchers has been invaluable in not only illuminating the techniques used by ancient tattooists but also in fostering a deeper appreciation for their artistry and skills, enriching our understanding of past societies and their intricate relationship with body modification.

High-resolution documentation of ancient tattooing methods is crucial for advancing our knowledge of past tattooing traditions. By eschewing a functional analysis of Scythian tattooing and instead narrowly focusing on the possible method of tattoo creation, we hope to have better explained the authorship of these images. While the individual in prehistory has been a topic of research for quite some time (e.g. Hill & Gunn Reference Hill and Gunn1977) these debates are largely missing from the archaeology of the Eurasian steppes. The detailed study of ancient tattoos provides an ideal opportunity to redress this, allowing us to further the post-processual goal of putting the prehistoric individual back in the picture.

Acknowledgements

We thank the curator of the Pazyryk collection of the State Hermitage Museum, Elena Stepanova, for her help in the organisation of the documentation process.

Funding statement

The work on the 3D digitisation of the mummy was funded by Staatliches Museum für Archäologie Chemnitz (Landesamt für Archäologie Sachsen).

Data availability

All data are contained within the manuscript.