Over the past 40 years, second language acquisition (SLA) researchers have paid much attention to how second language (L2) learners can develop their oral abilities according to a set of affecting variables, such as the quantity (Flege, Reference Flege, Piske and Young-Scholten2009) and quality (Jia & Aaronson, Reference Jia and Aaronson2003) of input and interaction, age of acquisition (Abrahamsson & Hyltenstam, Reference Abrahamsson and Hyltenstam2009), language aptitude (Granena, Reference Granena2013), motivation (Moyer, Reference Moyer1999), and willingness to communicate in the L2 (Derwing & Munro, Reference Derwing and Munro2013). Certain researchers (e.g., Llanes & Muñoz, Reference Llanes and Muñoz2013; Muñoz & Llanes, Reference Muñoz and Llanes2014) have recently begun to examine the extent to which the findings from naturalistic settings, where L2 learners are intensively exposed to a target language on a daily basis, are generalizable to foreign language (FL) learning conditions, typically characterized by a few hours of L2 input per week. The current study was designed to examine (a) the extent to which adolescent Japanese learners of EnglishFootnote 1 could enhance the global, segmental, prosodic, and temporal quality of their spontaneous speech solely after receiving 6 years of instruction (Grades 7–12) within FL classrooms; and (b) how the level of proficiency achieved was related to the length and focus of instruction that students had received as well as their language aptitude and motivation profiles.

BACKGROUND

Predictors for successful L2 speech learning

One of the most well-researched topics in SLA is the role of individual differences in determining adolescent and adult L2 learners' speaking ability in naturalistic settings (for a review, see Piske, MacKay, & Flege, Reference Piske, MacKay and Flege2001). For instance, it has been shown that late L2 learners' varied oral proficiency is likely determined by how much L2 input they receive and how they use the L2 to interact with other native and nonnative speakers. Although late L2 learners can choose to mainly use their first language (L1) within the same ethnic community even in an L2 speaking country, those who report high L2 use tend to demonstrate continued improvement in the segmental (e.g., Saito & Brajot, Reference Saito and Brajot2013) and suprasegmental (e.g., Trofimovich & Baker, Reference Trofimovich and Baker2006) aspects of pronunciation as well as listening comprehension skills and proper grammar usage (Flege & Liu, Reference Flege and Liu2001) after an extensive amount of L2 immersion. These studies have provided some evidence that late learners' L2 oral proficiency development can be characterized as a gradual, constant, and extensive process (Flege, Reference Flege, Piske and Young-Scholten2009).

Much research attention has also been directed toward the role of language aptitude in explaining the variability in adolescent and adult L2 speech learning. Language aptitude has been conceptualized as a subset of linguistic abilities, including phonetic coding (i.e., connecting sounds to relevant symbols), grammatical sensitivity (i.e., recognizing the functions of linguistic parts in sentences), and memory capacity (i.e., rote memorization). It has been measured by several tests, including the Modern Language Aptitude Test (Carroll & Sapon, Reference Carroll and Sapon1959), the Pimsleur Language Aptitude Battery (Pimsleur, Reference Pimsleur1966), and the LLAMA Language Aptitude Tests (Meara, Reference Meara2005). L2 language aptitude is essentially innate and independent of other cognitive characteristics of individual learners, such as attitude, motivation, and beliefs about the target language (Skehan, Reference Skehan2002). According to Ortega's (Reference Ortega2009) review, language aptitude scores likely explain 16%–36% (r = .4−.6) of variance in proficiency levels, final course grades, and teachers' ratings under instructed conditions. In addition, language aptitude has been found to predict the extent to which late learners can continue to enhance their L2 general performance and ultimately simulate nativelike performance (Granena, Reference Granena2013).

Finally, another index for late SLA is related to professional and integrative motivation. For example, certain L2 learners with a high degree of motivation to speak an L2 will likely demonstrate advanced L2 oral ability (e.g., Moyer, Reference Moyer1999). Derwing and Munro (Reference Derwing and Munro2013) recently conducted longitudinal research to investigate how late immigrants' English oral ability changed at three different time points across 7 years of residence in Canada. The results showed that while those with high willingness to communicate with other interlocutors in English progressively refined their L2 oral ability as a function of additional immersion, those without such communicative intentions exhibited little improvement over time. L2 learners' concern for pronunciation accuracy has also been shown to contribute to learners' reduced foreign accentedness (Flege, Munro, & MacKay, Reference Flege, Munro and MacKay1995).

In contrast, some empirical evidence exists showing that motivation is unrelated to L2 performance (Oyama, Reference Oyama1976; Thompson, Reference Thompson1991). This discrepancy in the literature suggests that defining what constitutes L2 learners' motivation in L2 speech learning is difficult, because the nature of motivation widely varies in relation to learners' goals, intentions, and self-images as well as their learning contexts (Dörnyei, Reference Dörnyei1994). Future research of this kind needs to precisely examine which aspects of learners' motivation relate to linguistic development, especially by elaborating valid methods for quantifying motivation (Piske et al., Reference Piske, MacKay and Flege2001).

Role of FL education

What has recently attracted an increasing amount of attention in the field of L2 education research is whether and to what degree the findings on L2 speech learning resulting from immersion under naturalistic conditions can be generalized to FL instructional settings. According to Larson-Hall (Reference Larson-Hall2008), the FL instruction involves “minimal input conditions” and typically constitutes “no more than four hours of instruction per week” (p. 36). As Muñoz (Reference Muñoz2008) pointed out, the following conditions typically characterize FL learning: (a) instruction is limited to two to four sessions of approximately 50 min per week; (b) exposure to the target language during these class periods may be limited in source (mainly the teacher), quantity (not all teachers use the target language as the language of communication in the classroom) and quality (there is large variability in teachers' oral fluency and general proficiency); (c) the target language is not the language of communication between peers; and (d) the target language is not spoken outside the classroom (pp. 578–579).

Although it is clear that attaining nativelike L2 performance solely based on such limited L2 experience is extremely difficult or even unrealistic (Derwing & Munro, Reference Derwing and Munro2009; Levis, Reference Levis2005), what remains unclear is the extent to which instruction alone can be facilitative of L2 oral ability development in the FL classroom. Investigating the efficacy of FL instruction is thus of critical pedagogical and theoretical relevance to late SLA for several reasons. First, many adult L2 learners still learn their L2 in such FL classrooms as preparation for future career- and academic-related goals. There has been some suggestion that what and how they learn from FL instruction as predeparture training strongly predicts the degree of positive change in the linguistic and affective dimensions of their SLA processes after they actually start working and studying abroad (e.g., DeKeyser, Reference DeKeyser2007). Second, although child SLA is generally facilitated by an extensive exposure to the target language (e.g., Flege, Reference Flege, Piske and Young-Scholten2009), recent longitudinal investigations have provided some evidence that late SLA greatly benefits from formal instruction (sometimes even more than study-abroad), especially when it comes to short-term improvement (e.g., Llanes & Muñoz, Reference Llanes and Muñoz2013; Muñoz & Llanes, Reference Muñoz and Llanes2014). These studies in turn suggest that further research on the facilitative role of FL instruction in late SLA is an important initiative.

Third, it is important to note that previous L2 education research (e.g., Spada & Tomita, Reference Spada and Tomita2010) has yet to reveal the pure effects of instruction on late SLA, especially from a longitudinal perspective. In response to some researchers' skepticism of any significant impact of formal instruction on acquisition (e.g., Krashen, Reference Krashen2013), many quasi-experimental intervention studies have been conducted in FL classrooms with pre- and posttest designs. The results have revealed that certain kinds of L2 instruction, especially those combining form and meaning in a complementary manner (i.e., focus on form), can facilitate learners' linguistic performance not only at a controlled but also at a spontaneous level (Norris & Ortega, Reference Norris and Ortega2000; Spada & Tomita, Reference Spada and Tomita2010). However, as Norris and Ortega (Reference Norris and Ortega2000) pointed out, these findings need to be interpreted with caution, because most of these instructed SLA studies have corroborated the pedagogical value of a brief amount of instruction. For example, the mean length of instruction of the 41 studies featured in Spada and Tomita (Reference Spada and Tomita2010) was approximately 3 hr, ranging from 20 min to 9 hr. In addition, these studies have documented learners' improvement on only a few targets due to the brevity of instructional treatment. Few studies have ever examined how much L2 learners can continue to improve in various linguistic areas of L2 oral ability after an extensive amount of instruction over a prolonged period of time.

Although much room for research on the role of instruction in late SLA still exists, some researchers have argued that studying a FL in a classroom setting may be unrelated to the development of L2 oral ability in particular. For example, FL classrooms have been criticized as “a restricted setting” (emphasis original, Best & Tyler, Reference Best, Tyler, Bohn and Munro2007, p. 19), because most lack the opportunity for systematic and abundant conversational experience with native speakers, which is thought to be the most important source of L2 speech learning (see also Long, Reference Long2007). This is because learners in many FL settings, such as Japanese students in English as an FL (EFL) classrooms (the focus of the study), learn the L2 for not only communication-oriented but also examination-driven purposes (Kozaki & Ross, 2008). Furthermore, language-focused methods (e.g., grammar-translation teaching) are likely considered the most preferred way of L2 instruction (Yashima, Zenuk-Nishide, & Shimizu, Reference Yashima, Zenuk-Nishide and Shimizu2004). It is important to note that Doughty (Reference Doughty, Long and Doughty2003) emphasized that instruction without much contextualized use of language simply leads to “the accumulation of metalinguistic knowledge about language” (p. 271); thus, what L2 learners learn through FL education may not necessarily be integrated into their interlanguage system (Jiang, Reference Jiang2007). Students who receive focus on form instruction often fail to generalize what they have learned to communicative contexts outside of classrooms (Gatbonton & Segalowitz, Reference Gatbonton and Segalowitz2005), and their improvement pattern for one grammatical target (e.g., progressives) is reported to be short-lived, especially when they move on to different structures (e.g., simple past; Lightbown, Reference Lightbown, Felix and Wode1983).

However, the quality of formal instruction has dramatically changed recently, especially thanks to the increasingly important role of English as an international language of communication in many parts of the world: many L2 learners of English have begun to consider the development of oral proficiency skills as a path to have successful social interaction in English in the context of a global society. For example, many secondary-level school students in Japanese FL classrooms are reported to have different kinds of intrinsic, instrumental, and integrative types of motivation to study English as an L2 (e.g., entrance examinations, cultural exploration, and future business; Kimura, Nakata, & Okumura, Reference Kimura, Nakata and Okumura2001). Since 2003, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology in Japan has introduced a range of educational reforms (i.e., an action plan to cultivate “Japanese with English abilities”) to emphasize the importance of using English as a practical tool for communication. As Yashima et al. (Reference Yashima, Zenuk-Nishide and Shimizu2004) pointed out, the FL context in Japan (and possibly in other East Asian countries) is multidimensional rather than monolithic, such that FL students have begun to study English to pursue not only “a short-term realistic goal related to examinations and grades” but also “a somewhat vague long-term objective related to using English for international/intercultural communication” (p. 121). In light of L2 learners' changing perceptions of the goal of L2 instruction, and the growing awareness of the value of oral communication and conversation activities in many FL classrooms, it is high time to reconsider the pedagogical potential and limitations of FL instruction.

MOTIVATION FOR CURRENT STUDY

Although few in number, some attempts have been made to investigate the effectiveness of extensive FL instruction in late SLA. One such example is Muñoz (Reference Muñoz and Muñoz2006), who conducted a longitudinal investigation on how Spanish–Catalan bilingual learners of English improved in a range of linguistic abilities. In this project, four groups of learners who started learning English at different ages (i.e., 8, 10, 14, and 18+ years) were compared at three different points of time after receiving the same amount of instruction (i.e., 2, 4, and 8 years). The results showed that their speaking performance, elicited via a range of oral tasks (e.g., picture narratives), increased over time regardless of their starting age profiles. Muñoz (Reference Muñoz and Muñoz2006) found similar outcomes in the domains of listening comprehension skills, fluency, and vocabulary. In addition, adolescent and adult learners actually tended to demonstrate earlier and more substantial gains from the same amount of L2 instruction as child learners. Adolescent and adult learners are able to do so by making the best of their cognitive maturity (e.g., advanced logical and deductive reasoning, and memory and processing capacities), literacy knowledge (e.g., larger L1 vocabulary size, and greater phonological and morphological awareness), and accumulated experience at school (e.g., familiarity to learning the L2 under minimal input conditions; see also Muñoz & Singleton, Reference Muñoz and Singleton2011).

The current study aimed to further examine how and to what extent FL instruction alone enables adolescent and adult learners to improve their L2 oral abilities. Specifically, we focused on analyzing the global (foreign accentedness), segmental (consonant and vowel errors), prosodic (word stress and intonation), and temporal (speech rate) quality of the spontaneous speech of 56 Japanese learners of English who had just finished 6 years of FL education in Japan (Grades 7 to 12 at 12–17 years old) without any experience abroad. Their performance was compared to that of 10 experienced late Japanese learners in Canada (+20 years of L2 immersion) who were assumed to represent the final state of SLA. Subsequently, we examined under what conditions such FL efficacy can be increased according to the length and focus of FL instruction that learners received, as well as their motivation and language aptitude profiles. Accordingly, two research questions were formulated as follows:

-

1. To what extent can an extensive amount of FL instruction (6 years) impact the development of adolescent L2 learners' oral ability?

-

2. Which variables (length and focus of instruction, frequent L2 conversation, aptitude, and motivation) predict the outcomes of late SLA in FL classrooms?

METHOD

Participants

FL students

In total, 56 freshman students at a university in Japan voluntarily participated in the study (age range = 18–19 years). Data collection was administered within 1 month after the students had entered the college. Students were recruited via a flyer that specified the necessary conditions for participating in the project:

-

• Participants must be native speakers of Japanese (they must have received language input only in Japanese from their native-speaking Japanese parents from birth).

-

• They had started learning English from secondary school (the fact that these students had not received any English lessons at elementary and/or private language school led us to assume that they had zero knowledge of English at the beginning of Grade 7).Footnote 2

-

• They had never traveled in English-speaking countries for more than 1 month. None had any prior study-abroad experience (this factor ensured that they had studied English only through FL instruction).

Participating students were majoring in either business and marketing, or international relations and liberal studies. According to their language background questionnaire, they received only a few hours of English lessons per week during junior high school and high school. As reported in previous research (e.g., Yashima et al., Reference Yashima, Zenuk-Nishide and Shimizu2004), the content of the FL syllabus in Japanese English education is typically twofold. Whereas teachers and learners focus on memorizing vocabulary and idiomatic expressions, practicing sentence translations and engaging in intensive and extensive reading as a main and short-term goal, they gradually start paying attention to oral communication and conversation activities as a secondary, long-term goal. The details of the length and type of FL instruction that the participants received are provided later.

Experienced Japanese learners

To establish a baseline for the current study (i.e., the upper limit of late L2 learners' oral performance), rather than using native speakers of English, the decision was made to recruit highly experienced Japanese learners of English who had already reached ultimate attainment due to their extensive amount of L2 experience. Many SLA scholars (e.g., Cook, Reference Cook2002; Ortega, Reference Ortega2009) have emphasized that any L2 phenomenon needs to be examined within nonnative speakers themselves rather than in relation to a native speaker model, given that few nonnative speakers can actually achieve perfect nativelike performance, especially when they start learning the L2 after the age of 12 (Abrahamsson & Hytemstam, Reference Abrahamsson and Hyltenstam2009), and that nonnative accents are a normal aspect of L2 speech production (Derwing & Munro, Reference Derwing and Munro2009; Flege et al., Reference Flege, Munro and MacKay1995).

In line with age-related SLA research standards (e.g., DeKeyser, Reference DeKeyser2013), 10 late experienced Japanese learners at the point of ultimate attainment were carefully recruited in Vancouver based on the quantity and quality of their extensive L2 experience. They had all arrived in Canada after the age of 18 (M age of arrival = 24.1 years), resided there for more than 20 years (M length of residence = 24.7 years), and reported that their main language of communication either at home or at work was English. According to their language background questionnaire, they demonstrated highly frequent use of English (M = 5.7 from 1 = very infrequent to 6 = very frequent).Footnote 3 Their performance was thus judged to well reflect the end state of late SLA, the result of much experience and practice, and was considered near nativelike in performance (Abrahamsson & Hyltenstam, Reference Abrahamsson and Hyltenstam2009).

Speaking task

L2 speech has traditionally been elicited via controlled speech tasks, such as paragraph and sentence readings (i.e., repeating audio and written prompts; Piske et al., Reference Piske, MacKay and Flege2001). However, because adult L2 learners can carefully monitor the linguistic forms they use (Jiang, Reference Jiang2007), such highly controlled performance has been criticized for eliciting “language-like behavior” rather than “actual L2 proficiency” (Abrahamsson & Hyltenstam, Reference Abrahamsson and Hyltenstam2009, p. 254). To tap into the present state of L2 learners' interlanguage representations, many SLA researchers have emphasized the importance of adopting spontaneous speech tasks, during which L2 learners are induced to pay equal attention to the phonological domain as well as the temporal, lexical, grammatical, and discoursal domains of language to convey their communicative intentions (Spada & Tomita, Reference Spada and Tomita2010) under time pressure (Ellis, Reference Ellis2005).

Similar to previous L2 pronunciation studies (e.g., Derwing & Munro, Reference Derwing and Munro2009; Trofimovich & Isaacs, Reference Trofimovich and Isaacs2012), participants' spontaneous speech was elicited via a timed picture description task. As conceptualized and validated in Saito, Tro-fimovich, and Isaacs (Reference Saito, Trofimovich and Isaacs2015), the task adopted in the study was carefully designed to elicit a certain length of spontaneous speech data without excessive hesitations and dysfluencies from the participants, who had a wide range of L2 proficiency. First, instead of using a series of thematically linked images (e.g., Derwing & Munro, Reference Derwing and Munro2009), speakers described seven separate pictures, with three keywords printed as hints. Second, to control for speakers' lack of familiarity with the task, the first four pictures were used for practice and the last three were targeted for analyses. Third, to minimize the amount of conscious speech monitoring (see Ellis, Reference Ellis2005), speakers were given only a very small amount of planning time (i.e., only 5 s) before describing each picture.

The three target pictures depicted a table left out in a driveway in heavy rain (keywords: rain, table, driveway), three men playing rock music with one singing a song and the other two playing guitars (keywords: three guys, guitar, rock music), and a long stretch of road under a cloudy blue sky (keywords: blue sky, road, cloud). The keywords were intentionally chosen to push Japanese learners to use problematic segmental and syllable structure features and show their pronunciation abilities. For instance, Japanese speakers have been reported to neutralize the English /r/–/l/ contrast (“rain, rock, brew, crowd” vs. “lane, lock, blue, cloud”) and to insert epenthetic vowels between consecutive consonants (/dəraɪvə/ for “drive,” /θəri/ for “three,” /səkaɪ/ for “sky”) and after word-final consonants (/teɪbələ/ for “table” and /myuzɪkə/ for “music”) in borrowed words (i.e., Katakana; for a comprehensive review, see Saito, Reference Saito2014).

All speech recordings were carried out individually with both the FL students and experienced Japanese learners in university labs using a digital Marantz PMD 660 audio recorder (44.1-kHz sampling rate with 16-bit quantization). To ensure that all speakers understood the procedure, the researcher (a native speaker of Japanese) delivered all instructions in Japanese. The participants then described the 7 pictures, using the first 4 pictures as a practice. The remaining 3 pictures (A, B, C, in that order) were used for the main analysis. In total, the speakers generated 168 picture descriptions (3 pictures by 56 Japanese, and 10 English speakers).

On average, about 5–10 s from the beginning of each description was extracted for each speaker. Three picture descriptions (Pictures A, B, and C) for each speaker were combined and stored in a single audio file, resulting in a total mean length of 25 s for the three picture descriptions combined (18.5–40.3 s). Compared to the 15- to 30-s samples used for rating in similar pronunciation studies (e.g., Derwing & Munro, Reference Derwing and Munro2009), the entire duration of these samples was considered to be sufficient for eliciting elicit listeners' impressionistic ratings of speech. In total, 66 speech samples were created from 56 FL students and 10 experienced Japanese learners.

Global analyses

The global quality of L2 speech was assessed by native speaking raters on the continuum of foreign accentedness. The accentedness index refers to how different an L2 speaker's accent sounds from that of the native-speaker community (e.g., Derwing & Munro, Reference Derwing and Munro2009) and is measured via naive listeners' intuitions without relying on training and background (e.g., Flege et al., Reference Flege, Munro and MacKay1995; Muñoz & Llanes, Reference Muñoz and Llanes2014). This measure has been extensively used in the previous L2 speech literature (e.g., Flege et al., Reference Flege, Munro and MacKay1995) and is reported to reflect various aspects of language, including pronunciation, fluency, vocabulary, and grammar (Trofimovich & Isaacs, Reference Trofimovich and Isaacs2012).

Raters

Following the definition of naive listeners in Isaacs and Thomson (Reference Isaacs and Thomson2013), five native speakers of English (two males, three females) were recruited at an English-speaking university in Montreal. The raters were born and raised in English-speaking homes in Canada (n = 3 in Montreal, 2 in Toronto). All of the raters (M age = 21.6 years) were undergraduate students with nonlinguistic backgrounds (e.g., business or psychology) and reported no previous teaching experience in SL/FL classrooms. They reported relatively low familiarity with Japanese-accented English (M = 1.8 from 1 = not at all to 6 = very much). None of the raters reported any hearing problems.

Procedure

The test was run offline using a custom software, Z-Lab (Yao, Saito, Trofimovich, & Isaacs, Reference Yao, Saito, Trofimvich and Isaacs2013), developed using commercial software package (MATLAB 8.1, MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, 2013). The raters used a free moving slider on a computer screen to assess the foreign accentedness of the speech samples. If the slider was placed at the leftmost end of the continuum, labeled with a frowning face (indicating very negative), it was recorded as 0; if it was placed at the rightmost end of the continuum, labeled with a smiley face (indicating very positive), it was recorded as 1000. The raters received a brief explanation of the construct of foreign accentedness from a trained research assistant. After a practice run, wherein the raters rated three speech samples (not included in the main data set), they listened to 66 speech samples in a randomized order. To tap into the initial intuitions and impressions of foreign accented speech, each sample was played only once for the raters' judgment. The listening test was designed such that the raters were allowed to make foreign accentedness judgments only after listening to the entire sample. The raters were always reminded that the entire speech samples well represented a wide range of Japanese learners of English with various proficiency levels (not only FL students but also experienced Japanese learners), and were thus encouraged to use the entire scale as much as possible. The whole session took approximately 1 hr.

Interrater reliability

Similar to previous research (e.g., Derwing & Munro, Reference Derwing and Munro2009), the five inexperienced raters showed high reliability values among their accentedness ratings (Cronbach α = 0.94). Thus, mean rating scores were calculated by pooling over the five inexperienced raters, and then given to each token produced by the participants.

Pronunciation and fluency analyses

In the study, L2 oral ability was defined not only as a broad concept of global foreign accentedness but also as a specific phonological phenomenon, spanning segmentals, prosody, and fluency (Trofimovich & Isaacs, Reference Trofimovich and Isaacs2012). Such subdomains of L2 speech have typically been measured via objective instruments of acoustic analyses (Piske et al., Reference Piske, MacKay and Flege2001). Because these measures are designed to analyze the segmental and temporal features of L2 speech when the phonetic contexts of the target sounds (e.g., following and preceding vowels, and speech and articulation rate) are strictly controlled, it remains unclear whether they can be appropriately applied to more uncontrolled and conversational speech samples.

In this regard, recent L2 pronunciation studies have also used extensively trained raters' subjective judgments of the pronunciation and fluency aspects of L2 speech. For example, previous research has examined segmentals (Piske, Flege, MacKay, & Meador, Reference Piske, Flege, MacKay, Meador, Wrembel, Kul and Dziubalska-Kołaczyk2011), prosody (Field, Reference Field2005), and temporal fluency (Bosker, Pinget, Quené, Sanders, & de Jong, Reference Bosker, Pinget, Quené, Sanders and De Jong2013; Derwing, Rossiter, Munro, & Thomson, Reference Derwing, Rossiter, Munro and Thomson2004). In these studies, native speaking raters (usually with much pedagogical and linguistic experience) directly assess specific aspects of L2 speech embedded in extemporaneous speech after receiving explicit training on the target sounds being evaluated. The human judgment method has been found to be highly trustworthy, because these raters can selectively attend to the targetlikeness of segmentals, prosody, and fluency by drawing on their own intuitions without being distracted by other nonnativelike use of language (e.g., vocabulary and grammar errors). Thus, the experienced human rating method was adopted in this study, whereby linguistically trained raters assessed pronunciation and fluency aspects of L2 speech using four measures (segmentals, word stress, intonation, and speech rate) developed in the extensive L2 speech research (e.g., Derwing et al., Reference Derwing, Rossiter, Munro and Thomson2004) and validated in a previous project (Saito, Trofimovich, & Isaacs, in press).

Raters

Different from the global analyses, following the definition of experienced raters by Isaacs and Thomson (Reference Isaacs and Thomson2013), five native-speaking raters (three males, two females) were recruited based on their linguistic and pedagogical experience. They were born and raised in English-speaking homes in Canada (three from Montreal, two from Ontario). All of them were graduate students in the Department of English at a university in Montreal. All of them had received training in phonetics and phonology and reported a sufficient amount of teaching experience in SL/FL settings (M = 4.0 years, range = 2–6 years). They reported relatively high familiarity with Japanese-accented English (M = 4.4 from 1 = not at all to 6 = very much). None of the raters reported any hearing problems.

Segmental, prosodic, and temporal measures

The raters listened to 66 samples played in a randomized order via Z-Lab (Yao et al., Reference Yao, Saito, Trofimvich and Isaacs2013). For each audio sample, they used the same moving slider (1000-point scale: 1 = nontargetlike, 1000 = targetlike) to evaluate four segmental, prosodic, and temporal aspects of L2 speech at the same time: (a) segmental errors (substitution, omission, or insertion of individual consonants or vowels); (b) word stress errors (misplaced or missing primary stress); (c) intonation (appropriate, varied versus incorrect and monotonous use of pitch); and (d) speech rate (speed of utterance delivery).

Procedure

The sessions took place in a quiet room on two different days, with the first day for training (about 3 hr), and the second day devoted to evaluating the audio files of the current data set (about 3 hr). For training scripts and onscreen labels for the audio-based measures, see Appendix A.

TRAINING PHASE

The five raters in the current study received thorough instructions from a trained research assistant on the eight different domains of pronunciation and fluency. The definitions and training transcripts were elaborated from previous research focusing on segmentals (Piske et al., Reference Piske, Flege, MacKay, Meador, Wrembel, Kul and Dziubalska-Kołaczyk2011), word stress (Field, Reference Field2005), intonation (Hahn, Reference Hahn2004), and speech rate (Derwing et al., Reference Derwing, Rossiter, Munro and Thomson2004). They then proceeded to practice the judgment procedure using the data set of Trofimovich and Isaacs (Reference Trofimovich and Isaacs2012), which consisted of a total of 40 nonnative speakers' picture narratives.

As separately reported in detail in Saito et al. (in press-b), the validity of their pronunciation and fluency judgments were examined from various angles. In terms of the accuracy of their ability to judge specific phonological features in L2 speech, the raters' pronunciation and fluency judgment scores were compared with the corresponding linguistic properties that Trofimovich and Isaacs (Reference Saito, Trofimovich, Isaacs, Webb, Isaacs and Trofimovich2012) measured via a range of objective instruments (e.g., acoustic analyses). The results identified significant correlations between the pronunciation and fluency ratings and the relevant linguistic dimensions, which are briefly summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Correlations between pronunciation and fluency ratings and coded linguistic variables in the training data set

Note: The results of the correlation analyses were retrieved from Reference Saito, Trofimovich, Isaacs, Webb, Isaacs and TrofimovichSaito et al. (in press).

a α < 0.05.

In addition, the raters not only demonstrated relatively high interrater agreement calculated by the Cronbach α values for segmentals (0.93), word stress (0.93), intonation (0.91), and speech rate (0.94) but also reported a high level of understanding of each category on a 9-point scale (1 = I did not understand this concept at all; 9 = I understand this concept well) for segmentals (M = 8.9), word stress (M = 8.7), intonation (M = 8.7), and speech rate (M = 8.9).

RATING PHASE

On the second day, they first recapped the main points of Day 1 and made preparations for the rating procedure in the main rating sessions. After receiving a review of the instructions on the four pronunciation and fluency categories and familiarizing themselves with the picture prompts and key words for the current data set, the five raters practiced rating five practice samples (i.e., picture descriptions of Japanese learners not included in the main analysis). For each sample, the raters explained their decisions and received feedback on their accuracy based on their understanding of the categories. Subsequently, the raters proceeded to perform audio-based judgments of 66 audio files.

Interrater reliability

Similar to the training phase, high interrater agreement was found among the five experienced raters' linguistic judgment in terms of pronunciation (Cronbach α segmentals = 0.97: α word stress = 0.95, α intonation = 0.94) and fluency (α speech rate = 0.95). The raters' scores were therefore considered sufficiently consistent and were averaged across five experienced raters to derive a single score per rated category for each speaker.

Interrelationships between linguistic scores

Simple correlation analyses were performed to investigate the degree of independence between the audio ratings (see Table 2). A Fisher r to z transformation was also conducted to check the different strengths of the correlation coefficients (p = .008, Bonferroni corrected). For the audio-based measures, the raters' segmental scores were more strongly related to their word stress scores (r = .96) than their speech rate scores (r = .76, p < .001). The speech rate scores were more closely related to intonation (r = .92) than to segmentals (r = .76, p < .001) or word stress (r = .80, p = .006). The results suggested that the four rater-based linguistic categories were considered to tap into three domains of L2 phonological proficiency: correct word pronunciation (segmentals and word stress), prosody (word stress and intonation), and rhythmic fluency (intonation and speech rate).

Table 2. Intercorrelations between the audio ratings

Questionnaire instruments

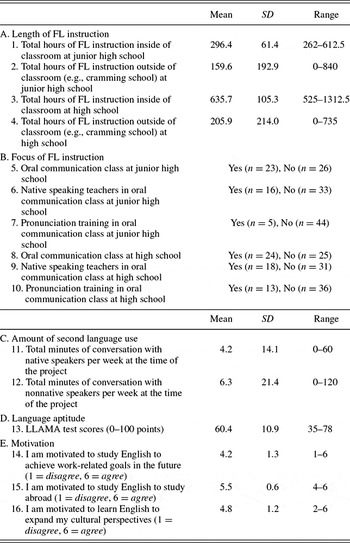

The FL students filled out a questionnaire that consisted of a set of items regarding the length and focus of FL instruction they had received in junior high school and high school as well as the frequency of L2 conversation and their motivation for learning English at the time of the project (see Table 3). Acknowledging that the construct validity of self-reports remains controversial because some students may have difficulty remembering (Piske et al., Reference Piske, MacKay and Flege2001), the participants were guided to report their previous FL learning experience during interactive interviews with the researcher, similar to what was done in Muñoz (Reference Muñoz2014). The items included for the final analysis were grouped into four subcategories:

-

1. Length of instruction: Although previous FL studies do not agree on the significance of age of initial learning on acquisition (Larson-Hall, Reference Larson-Hall2008; vs. Muñoz, Reference Muñoz and Muñoz2006), length of instruction has been found to be a significant predictor of FL success (Muñoz, Reference Muñoz2008, Reference Muñoz and Llanes2014). Following FL research standards, the length of instruction was measured by asking participants to retrospectively self-report the total number of hours of FL instruction inside (e.g., English language arts lessons) and outside (e.g., cram schools) the classroom in junior high school and high school.

-

2. Focus of instruction: It has been documented that Japanese EFL classrooms have begun to increase the amount of speaking activities and the number of native-speaking teachers, despite their continuing strong emphasis on exam preparation through grammar translation teaching methods (e.g., Kozaki & Ross, Reference Kozaki and Ross2011). In addition, certain L2 education researchers have emphasized the key role of pronunciation training as a part of oral communication classes in order to enhance the perceived comprehensibility of students' speech (Derwing & Munro, Reference Derwing and Munro2009). In our study, the presence of not only oral communication classes (taught by native and nonnative teachers) but also any pronunciation training during junior high school and high school was surveyed through the questionnaire.

-

3. Frequency of L2 conversations: Given the significant role of frequent L2 use through conversations with native and nonnative speakers in late SLA in naturalistic (Flege, Reference Flege, Piske and Young-Scholten2009) and classroom (Muñoz, Reference Muñoz and Llanes2014) settings, we also examined if this variable facilitated L2 oral ability development under FL conditions. As in previous research (Flege, Reference Flege, Piske and Young-Scholten2009), the participants were asked to self-report the total number of minutes of conversation with native and nonnative interlocutors per week at the time of the project. Unlike the oral communication classes, which provided teacher-centered speaking activities, this factor was included to reveal to what degree the participating students made an effort to find other native and nonnative speakers of English in Japan, and actually interact with them in English in a meaningful manner.

-

4. Motivation: The L2 motivation questionnaire was carefully tailored to the Japanese EFL context, where FL students likely have “dual orientations for studying English” with an equal focus on test preparation and intercultural communication (Yashima et al., Reference Yashima, Zenuk-Nishide and Shimizu2004, p. 121). FL students were asked to rate the amount of their integrative (e.g., expanding cultural knowledge and perspectives or making English-speaking friends) and instrumental (e.g., studying and working abroad) motivation for learning English on a 6-point scale (1 = disagree, 6 = agree).

Table 3. Descriptive statistics of individual differences among 49 foreign language (FL) students

Language aptitude

The FL students' language aptitude was measured by the LLAMA test (Meara, Reference Meara2005). Building on the Modern Language Aptitude Test (Carroll & Sapon, Reference Carroll and Sapon1959), the LLAMA consists of four subtests focusing on vocabulary learning, grammatical inference, sound–symbol correspondence, and sound recognition. The entire testing session took approximately 30 min. Similar to previous research on the relationship between LLAMA test scores and naturalistic SLA (Granena, Reference Granena2013), the participants' language aptitude was calculated using a composite score derived from their individual performance on each subtest (recorded from 0 to 100).

RESULTS

Individual differences among FL students

The first aim of the statistical analysis was to provide an overview of the individual differences among the 56 FL students. Because 7 participants did not complete all of the items on the questionnaire for various individual reasons, the descriptive results reported here were based on the questionnaires of 49 students (see Table 3). Over 6 years of secondary school education in Japan, the participants received an average of 932.1 hr of FL instruction (range = 875–1662) and 365.5 hr of extra FL activities, such as assignments and cram school instruction (range = 0–1155). At the time of the project, the students reported very limited opportunities to speak in the L2 with native speakers and nonnative speakers outside of the classroom, spending approximately only 5 min per week. Based on the above, it can be said that the learning environment of the participants in this study concurs with the preexisting definition of FL classrooms (Larson-Hall, Reference Larson-Hall2008; Muñoz, Reference Muñoz2008).

With respect to the focus of FL instruction, about a half of the students reported that their syllabus included oral communication that was primarily taught by either Japanese English teachers or native-speaking teachers. Despite the importance of pronunciation instruction in L2 speech learning as noted by many experts (e.g., Derwing & Munro, Reference Derwing and Munro2009), only a small portion of the students reported receiving pronunciation-focused training (n = 5 for junior high school, n = 13 for high school). The results of the LLAMA test indicated that the students had very diverse language aptitude profiles (35–78 out of 100 points). Finally, although the students were equally motivated to learn English to study abroad in the near future, the levels of their professional (job related) and integrative (expanding cultural perspectives) motivation varied greatly.

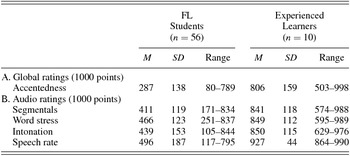

Effects of FL instruction

The second aim of the statistical analysis was to closely examine and compare the L2 oral ability of Japanese FL students and experienced Japanese immigrants in Canada. As summarized in Table 4, the students' speaking performance was positively evaluated, with mean linguistic scores of 500 out of 1000 in all of the global and phonological domains. Because none of the participants were rated as 0, the results indicated that 6 years of FL instruction did make some tangible impact on the Japanese students' pronunciation and fluency abilities as well as their overall foreign accentedness. At the same time, their performance was subject to a great deal of individual variability (i.e., their linguistic scores widely ranged from 100 to 800).

Table 4. Means and standard deviations for rated global, segmental, prosodic, and temporal qualities of foreign language (FL) students and experienced Japanese learners' picture descriptions

Note: A 1000-point scale was used: 1 = nontargetlike production, 1000 = targetlike production.

A set of independent-samples t tests showed that their performance was significantly different from that of the experienced Japanese learners with large effects for foreign accentedness (t = −10.69, p < .001, d = 3.48), segmentals (t = −10.53, p < .001, d = 3.62), word stress (t = −9.97, p < .001, d = 3.25), intonation (t = −7.79, p < .001, d = 3.03), and speech rate (t = −7.16, p < .001, d = 3.17). In addition, we also examined how many FL students could reach the range of these experienced Japanese learners' performance. Following the research literature on nativelikeness (see DeKeyser, Reference DeKeyser2013), we calculated the means and standard deviations of the baseline group for each speech measure, and then counted how many FL students' oral performance fell within 2 SD of the baseline mean values. Out of the 56 FL students, very few reached this nativelike performance for accentedness (n = 4), segmentals (n = 2), word stress (n = 3), and intonation (n = 7). Furthermore, none of them showed such high proficiency in terms of speech rate.

Predictors for successful FL learning

The third aim of the statistical analysis was to identify which variables (length and focus of instruction, L2 conversation, language aptitude, and motivation) influenced the individual differences among the FL students' oral ability. To this end, we report here whether the 16 variables were significantly related to the FL students' global and phonological aspects of L2 speech using Spearman rho correlation analyses, and how these variables differentially interact to predict the students' oral ability using factor and regression analyses.

Correlation analyses

As seen in Table 3, some items on the questionnaire had very large standard deviations (e.g., Q2, Q4, Q11, and Q12). Thus, a set of Spearman rho correlation analyses (appropriate for nonparametric data) was conducted to check for the presence of any significant link between the 16 questionnaire variables and 5 proficiency scores. According to the results (Table 5), four significant predictors were identified including: (a) the total amount of instruction outside of high school (for accentedness, segmentals, and word stress); (b) pronunciation training in high school (for segmentals); (c) the frequency of conversations with nonnative speakers at the time of the project (for all measures); and (d) aptitude (for segmentals, word stress, and speech rate).

Table 5. Correlations between 16 questionnaire variables and five speech measures

*p < .05. Denotes statistical significance.

Factor and regression analyses

While the correlation analyses found a general pattern that the FL students' oral ability significantly varied according to the aforementioned affecting variables, it was important to further pursue the relative predictive power of these variables for the impact of FL instruction on L2 speech learning. To avoid multicollinearity problems, we examined the set of 16 predictors in Table 3 to see if it could be reduced by combining the predictors into factors. The raw questionnaire scores were submitted to a principal component analysis (PCA) with Varimax rotation and the Kaiser criterion eigenvalue set at 1. The factorability of the entire data set was examined and validated via two tests: Bartlett's test of sphericity (χ2 = 295.35, p < .001) and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy (0.361).

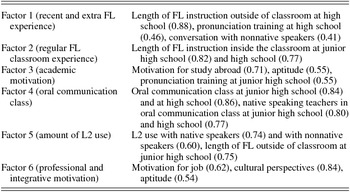

As summarized in Table 6, the PCA revealed six factors accounting for 69.1% of the total variance in the original data set. The resulting six PCA factors were then used as predictor variables in separate stepwise multiple regression analyses to examine their contribution to the global, segmental, prosodic, and temporal qualities of the FL students' oral ability, respectively.

Table 6. Summary of a six-factor solution based on a principal component analysis of the 16 predictors

Note: All eigenvalues > 1. FL, Foreign language; L2, second language.

To determine the appropriateness of conducting a set of multiple regression analyses with a relatively small sample size (N = 49), several necessary conditions were carefully checked. First, as explained above, the 16 predictors originally included in the questionnaire were reduced to 6 predictors by way of PCA. Second, the normality of each dependent variable (the global, segmental, prosodic, and temporal scores) was confirmed by Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests (p > .05). Third, it was determined that the power to find a medium effect size in a multiple regression with 49 participants was 0.58, which has been considered a minimum requirement (>0.50) in the field of SLA research (Larson-Hall, Reference Larson-Hall2010).

According to the results of the multiple regression analyses, Factor 1 significantly explained variance in foreign accentedness (14.7%), segmentals (16.3%), and word stress (16.4%); the other factors did not reach statistical significance as predictors for the FL students' L2 oral ability (see Table 7). Factor 1 consisted of three variables (length of FL instruction outside of the classroom during high school, pronunciation training in high school, and conversation with nonnative speakers at the time of the study), and was labeled “recent and extra FL experience.” This is because the variables clustered in this factor concerned the degree to which the students maximized their FL experience beyond the regular syllabus at school via cram schools, pronunciation training, and conversation with nonnative speakers, especially in the latter part of FL education (Grades 10–12).

Table 7. Significant results of multiple regression analyses using the foreign language (FL) factors as predictors of second language oral ability

Table 8. Correlation coefficients between foreign accentedness and four rated linguistic categories

*p < .003. Denotes statistical significance.

Linguistic correlates of foreign accentedness

The fourth aim of the statistical analysis was to examine how the global construct of L2 oral ability (foreign accentedness) was related to the four linguistic categories (segmentals, word stress, intonation, and speech rate) that tapped into three domains of L2 phonological proficiency: correct word pronunciation (segmentals and word stress), prosody (word stress and intonation), and rhythmic fluency (intonation and speech rate). The results of the simple correlation analyses (α = 0.003, Bonferroni corrected) showed that foreign accentedness was significantly correlated with all linguistic categories (segmentals, word stress, intonation, and speech rate), and its relationship with correct pronunciation of words (segmentals and word stress) was particularly strong (r > .70).

DISCUSSION

In light of the growing body of empirical evidence showing that older and more cognitively mature learners can achieve greater gains at a faster rate compared to younger learners when the amount of L2 input and interaction is extremely limited in FL settings (e.g., Muñoz & Singleton, Reference Muñoz and Singleton2011), the main purpose of the current study was to further scrutinize the complex mechanisms underlying the facilitative role of FL instruction in late L2 oral ability learning. To this end, we analyzed the global, phonological, and temporal qualities of the spontaneous speech of Japanese freshman college students with a history of FL instruction from Grades 7 to 12, and no experience abroad.

Our first research question asked to what extent extensive FL instruction impacted the development of adolescent learners' oral abilities. Compared to when they started learning English (Grade 7, with no knowledge of the target language), the students demonstrated intermediate-level linguistic scores (300–500 out of 1000 points) for their L2 speaking performance in terms of foreign accentedness as well as pronunciation and fluency abilities at the time of the project (when they had completed 6 years of FL learning). Their performance as a whole (n = 56) was significantly different from a baseline group of experienced Japanese learners in Canada who had reached the final state of naturalistic SLA after 20 years of L2 immersion. Very few of our participants reached the range of the baseline group's performance solely based on FL instruction. In response to the debate on the role of FL instruction (which is likely decontextualized in nature and void of ample opportunities for conversation) in late SLA (Norris & Ortega, Reference Norris and Ortega2000; vs. Spada & Tomita, Reference Spada and Tomita2010), these results provided some indication regarding its potentials (i.e., some positive change in all domains of learners' linguistic competence) and limitations (i.e., much room for improvement compared to ultimate attainment in naturalistic settings).

As for our second research question, which examined the variables predicting successful late SLA in FL classrooms, it is important to emphasize here that these FL students' oral ability varied greatly, and that some of the FL students reached the proficiency range of experienced Japanese learners. Why did certain FL students show such high-level oral ability? In line with previous research, the results of the correlation analyses demonstrated that their L2 oral ability levels were significantly related to the length of instruction (Muñoz, Reference Muñoz and Muñoz2006), pronunciation training (Saito, Reference Saito2012), current frequency of L2 conversation opportunities (Muñoz, Reference Muñoz and Llanes2014), and language aptitude (Ortega, Reference Ortega2009).

It is interesting that the results of multiple regression analyses further revealed how these predictors interacted to determine the FL students' widely diverse speaking performance (global foreign accentedness, segmentals, and word stress), which was particularly explained by a composite factor consisting of three variables related to “recent and extra FL experience.” That is, to make the best of FL instruction under restricted input conditions, what is important seems to be (a) how much the students practiced English outside of classrooms during high school; (b) whether they received pronunciation training during their high school oral communication classes; and (c) how often they used the L2 in oral communication, especially with nonnative speakers, at the time of the project. To summarize, whereas 6 years of FL instruction itself (>875 hr) led to tangible gains in all linguistic domains of L2 speech, regardless of students' various language aptitude and motivation profiles, certain students with greater amounts of extra FL activities tended to demonstrate better pronunciation abilities, and to speak with less perceived foreign accentedness.

Our results here concur with those of Muñoz's (Reference Muñoz and Llanes2014) FL study that found a range of extracurricular practice activities (e.g., watching TV, writing letters/emails, reading books, and conversations with native and nonnative speakers) to be significant predictors of the fluency aspects of students' oral performance. To date, the advantages of pronunciation training (e.g., Saito, Reference Saito2012) and social interaction (e.g., Flege, Reference Flege, Piske and Young-Scholten2009) for adolescent and adult SLA has been extensively documented in the previous literature. However, it is uncertain why the amount of practice in cram schools outside of high school (range = 612–1332 hr) was strongly related to successful FL learning in this study. Given that the chief goal of cram schools is to prepare Japanese high school students for entrance exams, it is reasonable to assume that these exams reflect what is studied in cram schools. The content of entrance exams consists mainly of reading (50% for School of International Liberal Studies, 100% for School of Commerce) and listening (30% for School of International Liberal Studies) comprehension questions; the exams are essentially designed to measure students' abilities to comprehend (but not necessarily produce) written and oral texts within time limits.

The content of the exams mentioned above leads us to speculate about two broad patterns regarding the nature of FL activities that many FL students, at least our participating students, typically experience during high school. At first, students may initially start with decontextualized activities, such as rote vocabulary memorization and discrete grammar exercises. Yet, they may ultimately be pushed toward a great deal of comprehension practice, such as intensive and extensive reading and listening activities, especially in cram schools, where they invest extra money and time with the view of attaining high scores in the entrance exams. According to comprehension-based teaching proposals, exposing L2 learners to large amounts of oral and written input may be one of the most beneficial ways to lead to successful learning, not only in comprehension, but also in the production, especially for beginner L2 learners with emerging L2 knowledge (e.g., Asher, Reference Asher1969, for total physical response; Krashen, Reference Krashen2013, for the natural approach; VanPatten, Reference VanPatten2004, for processing instruction).

Taken together, the results of this study suggest that certain L2 students can attain relatively advanced oral proficiency under FL conditions, especially when they have extra opportunities to improve not only their production performance via pronunciation training and conversation with nonnative speakers but also their comprehension skills via a great deal of reading/listening practice beyond the regular FL syllabus. At the same time, it is also important to remember that most of such successful FL learners substantially failed to reach the upper limits of naturalistic SLA: the high-level L2 speaking performance represented by the experienced Japanese learners in Canada. Thus, the FL-only approach may not always be ideal for adequately proficient L2 learners, because their speaking performance levels off somewhat after extensive amounts of FL instruction (e.g., Trofimovich, Lightbown, Halter, & Song, Reference Trofimovich, Lightbown, Halter and Song2009). At this point, it is suggested that students need to be pushed to engage in intensive exposure to L2 input and interaction, especially via study-abroad programs, and further refine the accuracy and fluency of their output abilities (DeKeyser, Reference DeKeyser2007).

The last factor for discussion relates to the optimal timing of receiving L2 input. It is important to reiterate that the above-mentioned significant predictors for successful FL learning included what the participating students had done in Grades 10 to 12 (high school), not in Grades 7 to 9 (junior high school). Our results are consistent with previous research, which shows that successful L2 learning in FL settings can be linked to the amount of L2 input received (i.e., how much students studied the target language inside and outside of FL classrooms; Munoz, Reference Muñoz and Llanes2014). In addition, our study contributes to the field by demonstrating that such FL efficacy may be strongly related to the type (what kinds of pedagogical activities students were involved with) and timing (how recently students received and experienced such instructional treatment) of L2 input. Although much discussion has been directed toward the quality and quantity of L2 input in late SLA, few studies have explored how the L2 experiences that learners have at different points of time affect SLA processes (e.g., Flege, Reference Flege, Piske and Young-Scholten2009). This is possibly because it is methodologically difficult to measure and define L2 experience by keeping track of the amount, type, and timing of the target language exposure of certain L2 learners via longitudinal research designs (cf. Ranta & Meckelborg, Reference Ranta and Meckelborg2013).

Usage-based theoretical accounts of SLA have emphasized that humans learn language as “optimal word processors” (Ellis, Reference Ellis2006, p. 8). As such, L2 learners are adaptively sensitive to not only how often (i.e., frequency) but also how recently (i.e., immediacy) certain linguistic items are used in particular discourse situations (i.e., contexts). As experience with the L2 increases, therefore, learners can attain increasingly robust associative representations by which to quickly and accurately predict and use the most relevant linguistic constructions in response to any linguistic and contextual cues. Extending this line of thought, the results of the study suggest that it is not only how much and in what way but also when FL students practice the target language that relates to successful FL learning. Whereas some researchers have debated the role of early English education in FL contexts, arguably because it provides FL learners with a larger amount of instruction and practice (Larson-Hall, Reference Larson-Hall2008; vs. Muñoz, Reference Muñoz and Muñoz2006), our findings add that the nature and timing of FL instruction need to be taken into account for the purposes of designing optimal FL syllabi.

Conclusion and future directions

To our knowledge, the current study was one of the first attempts to provide a comprehensive picture of the impact of FL instruction on L2 oral ability learning under restricted input conditions. In the context of Japanese EFL students, the results provide three broad findings: first, the participants' oral performance widely varied in relation to the length and focus of FL instruction, the frequency of their conversations in the L2, and aptitude; second, their diverse proficiency was particularly predicted by the amount of extra FL activities inside (i.e., pronunciation training) and outside (i.e., cram school) of high school (but not junior high) classrooms; and third, very few reached the proficiency range of the baseline group's near-nativelike performance solely based on FL instruction. The results in turn suggest that whereas extensive FL instruction (>875 hr) itself does make some difference in L2 oral ability learning, its pedagogical potential can be increased by how students optimize their most immediate FL experience beyond the regular syllabus.

Given the exploratory nature of the project, several directions need to be addressed for future FL studies of this kind. First, it is crucial to acknowledge that the sample size of the study was relatively small, as evidenced by the small to medium power (cf. Larson-Hall, Reference Larson-Hall2010). The findings are based on participants with widely varying proficiency levels and heterogeneous FL profiles, and thus should be considered as tentative. Therefore, the results of the study need to be replicated with different methodologies in the context of a larger number of FL learners with various L1/L2 backgrounds. For example, although the current study exclusively concerned foreign accentedness, some L2 speech researchers (e.g., Derwing & Munro, Reference Derwing and Munro2009) have argued that L2 learners' oral ability should be measured based on ease of understanding (i.e., comprehensibility) and speech intelligibility, given that even heavily accented speech can be highly comprehensible and intelligible to interlocutors (Levis, Reference Levis2005). Furthermore, given that the language aptitude variable (measured via the LLAMA test) was identified as a significant predictor of the effectiveness of FL instruction, it would be intriguing to test the generalizability of the findings together with other major language aptitude tests used in the field of SLA (see Ortega, Reference Ortega2009). Future FL studies also need to further examine other affecting variables not included in the current investigation, such as language and cognitive skills (De Jong, Steinel, Florijn, Schoonen, & Hulstijn, Reference De Jong, Steinel, Florijn, Schoonen and Hulstijn2012).

Second, it is worth noting that the results of the study were exclusively based on spontaneous speech elicited from the timed picture description task. The generalizability of the findings should be tested with different task modalities, because native speakers tend to perceive the same L2 learners' oral abilities in a significantly different manner according to how their speech is elicited. Derwing et al. (Reference Derwing, Rossiter, Munro and Thomson2004) showed that L2 learners' comprehensibility and fluency scores were rated more positively in monologue- and dialogue-based tasks than in a picture–narrative task (see also Crowther, Trofimovich, Isaacs, & Saito, Reference Crowther, Trofimovich, Isaacs and Saito2015). According to the task-based SLA literature, in tasks requiring online planning, L2 learners tend to use more appropriate lexical items with correct grammar (Yuan & Ellis, Reference Yuan and Ellis2003), and appear to produce more complex but less speech in tasks requiring some form of decision and subjective opinions (Skehan, Reference Skehan2009).

Third, another promising direction for future research is exploring the impact of listener characteristics. The Japanese students' overall proficiency (i.e., foreign accentedness) was judged by native speakers of English who reported little familiarity with Japanese-accented English. Future research may recruit various raters, both native and nonnative speakers (Derwing & Munro, Reference Derwing and Munro2013), with and without familiarity with foreign accented speech in the target language (Winke, Gass, & Myford, Reference Winke, Gass and Myford2013), and with varying degrees of linguistic and pedagogical experience (Saito, Trofimovich, Isaacs, & Webb, in press).

APPENDIX A

Training materials and onscreen labels for pronunciation and fluency judgment

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to the reviewers and Associate Editor Patricia Cleave for their constructive feedback on earlier versions of the manuscript. We also acknowledge George Smith and Ze Shen Yao for their help for data collection and analyses. The project was funded by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research 26770202 in Japan and Sanken Research Grant 2014-01 (to K.S.) and Grant-in-Aid for JSPS Fellow 244722 (to K.H.).