Anger is a common symptom among adults seeking outpatient mental health treatment. Anger, because it is often associated with substantial hostility and aggression,Reference Smith 1 may be clinically significant. In one study including 1300 adults presenting for outpatient psychiatric treatment, approximately half reported experiencing a moderate to severe level of anger, and about one-quarter reported extreme anger leading to aggressive behavior.Reference Posternak and Zimmerman 2 In extreme or dysfunctional forms, anger may also lead to adverse health consequencesReference Frasure-Smith and Lespérance 3 and may trigger maladaptive behaviors, including workplace hostility,Reference Kassinove and Sukhodolsky 4 domestic violence,Reference Maneta, Cohen, Schulz and Waldinger 5 and criminal behavior.Reference Swogger, Walsh, Homaifar, Caine and Conner 6

In clinical samples, anger has been associated with a wide range of psychiatric disorders. Anger is common among patients with depression and anxiety,Reference Posternak and Zimmerman 2 , Reference Dougherty, Rauch and Deckersbach 7 and correlates with the severity of depressive episodes.Reference Fraguas, Papakostas and Mischoulon 8 Anger is also a frequent problem in individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).Reference Chemtob, Novaco, Hamada, Gross and Smith 9 , Reference Feeny, Zoellner and Foa 10 The prevalence of anger is also elevated among individuals with panic disorder, agoraphobia, and cluster B and C personality disorders,Reference Gould, Ball and Kaspi 11 and among individuals who use tobacco, alcohol, or illegal substances.Reference Litt, Cooney and Morse 12 – Reference Patterson, Kerrin, Wileyto and Lerman 14

Anger has also been linked to several sociodemographic characteristics. Inverse associations exist between age, socioeconomic status, and anger.Reference Schieman 15 Aggression, which might be triggered by anger,Reference Alia-Klein, Goldstein and Tomasi 16 appears to be more common among younger individuals, who are more likely to be perpetrators and victims of violence than other age groups.Reference Truman and Rand 17 Whether a similar pattern exists for anger in the general population is not known. A greater understanding of the epidemiology of anger might help inform public health education and clinical efforts aimed at reducing or preventing poorly controlled anger. In the following analysis of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) survey results, a nationally representative sample of the adult population of the United States, we assess the prevalence, as well as the sociodemographic and clinical correlates of anger, in the general population and characterize adults that report inappropriate, intense, or poorly controlled anger.

Methods

Sample

Study subjects were drawn from Wave 2 of the NESARC (2004–2005), which has been described in detail elsewhere.Reference Grant, Kaplan and Stinson 18 The target population of the NESARC was the civilian non-institutionalized population 18 years and older residing in households and group quarters. Blacks, Hispanics, and adults 18–24 were oversampled, with data adjusted for oversampling, household-, and person-level nonresponse.Reference Grant, Hasin and Stinson 19 The fieldwork for this survey was completed under the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism's (NIAAA) direction by trained U.S. Census Bureau Field Representatives. Data were collected through computer-assisted personal interviews (CAPI) in face-to-face household settings. All potential NESARC respondents were informed in writing about the nature of the survey, the statistical uses of the survey data, the voluntary aspect of their participation, and the federal laws that rigorously provide for the confidentiality of identifiable survey information. Participants who completed the survey were given $80. 20 The sample in Wave 1 included 43,093 respondents ages 18 and older, representing the civilian, noninstitutionalized, adult population in the United States, including all 50 states and the District of Columbia. Excluding respondents ineligible for the Wave 2 interview (eg, deceased), the Wave 2 response rate was 86.7%, resulting in 34,653 completed interviews.

Assessment

All NESARC participants were asked three questions related to anger in Wave 2 of the NESARC. These questions were as follows:

-

1. Have even little things made you angry or have you had difficulty controlling your anger?

-

2. Have you often had temper outbursts or gotten so angry that you lose control?

-

3. Have you hit people or thrown things when you got angry?

Cronbach's alpha for the items was 0.74, indicating good internal consistency.

Following each question, subjects were asked about the impact of their anger on their lives. Only individuals who answered affirmatively to the follow-up question “Did this ever trouble you or cause problems at work or school, or with your family or other people?” were defined in this study as having inappropriate, intense, or poorly controlled anger. We also examined the association between each anger question and psychiatric disorders. Furthermore, to examine the severity of this type of anger, respondents were grouped into those who answered positively to 1 of the questions, those who answered positively to 2 questions, and those who answered positively to all 3 questions.

Sociodemographic measures included sex, race/ethnicity, nativity, age, education, marital status, and place of residence. Socioeconomic measures included employment status, and personal and family income measured as categorical variables. Using Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV) criteria, the presence of Axis I conditions was assessed by means of the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-DSM-IV Version (AUDADIS-IV).Reference Grant, Dawson and Stinson 21 This structured interview was designed for experienced lay interviewers. Extensive AUDADIS-IV questions covered DSM-IV criteria for alcohol- and drug-specific abuse and dependence for 10 classes of substances. Mood disorders included DSM-IV primary major depressive disorder (MDD), bipolar I, and bipolar II disorder. Anxiety disorders included DSM-IV primary panic disorder (with and without agoraphobia), social anxiety disorder and specific phobias, and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). Diagnoses of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) were also assessed in Wave 2. Conduct disorder and personality disorders were assessed on a lifetime basis at Wave 1, and were described in detail elsewhere.Reference Ruan, Goldstein and Chou 22 The latter included avoidant, dependent, obsessive-compulsive, paranoid, schizoid, histrionic, and antisocial personality disorders. Borderline, schizotypal, and narcissistic personality disorders were measured at Wave 2.Reference Ruan, Goldstein and Chou 22

Test–retest reliabilities for AUDADIS-IV mood, anxiety, personality disorders, and ADHD diagnoses in the general population and clinical settings were fair to good (κ=0.40–0.77). Test–retest reliabilities of AUDADIS-IV personality disorders compare favorably with those obtained in patient samples using semistructured personality interviews. Convergent validity was good to excellent for all affective, anxiety, and personality disorder diagnoses, and selected diagnoses showed good agreement (κ=0.64–0.68) with psychiatrist reappraisals.Reference Cottler, Grant and Blaine 23

Nondiagnostic variables were also included in the analysis. The presence of a psychotic disorder was assessed by asking the respondent if a doctor or other health professional had told the respondent in the last 12 months he/she had schizophrenia or a psychotic disorder. We also included variables measuring any substance use, any alcohol use, and any tobacco use during the last 12 months. The reliability of the alcohol consumption and drug use measures has been documented to range from good to excellent.Reference Grant, Dawson and Stinson 21 , Reference Hasin, Carpenter, McCloud, Smith and Grant 24

Life events and risk markers

The study further included life events and other variables that have been hypothesized to correlate with anger.Reference Dong, Giles and Felitti 25 , Reference Midei, Matthews and Bromberger 26 These variables included adverse childhood events such as physical neglect, verbal and physical abuse, emotional neglect, and sexual abuse. All questions about adverse childhood events referred to the respondents’ first 17 years of life. Questions were adapted from the Adverse Childhood Events studyReference Dube, Felitti and Dong 27 and derived from the Conflict Tactics ScaleReference Straus 28 and the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire.Reference Bernstein, Fink and Handelsman 29

Respondents were also queried about parental factors, including parental history of mood, substance, and alcohol use disorders, and antisocial personality disorder. Additionally, respondents were also queried on whether they had ever been sexually assaulted, molested, or raped; physically attacked or badly beaten up by their spouse or romantic partner or by somebody else; or if they had ever been married or lived with a person with alcoholism or problem drinking. Since these questions contained information on age at first occurrence and most recent occurrences, information was available for these events after age 18.

Other measures

Psychosocial functioning in the past month was assessed using subscales from the Short Form-12v2 (SF-12),Reference Ware, Kosinski, Turner-Bowker and Gandek 30 a reliable and valid measure of disability used in population surveys that includes the physical component summary and mental component summary. The SF-12 assesses respondents’ abilities in performing tasks or the degree to which physical or mental factors limit their activities. Each SF-12 disability scale yields a norm-based score with a mean of 50, a standardized range of 0–100, and a standard deviation (SD) of 10 for the U.S. general population. Individual results above or below 50 indicate scores higher or lower than those of the general population, respectively. The reliability and validity of the SF-12 has been well documented in a wide range of samples including medical settings (eg, myocardial infarction, chronic pain) and in the general population.Reference Ware, Kosinski, Turner-Bowker and Gandek 30

Statistical analyses

Weighted percentages, means, and odds ratios (ORs) were computed to derive sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of respondents with and without a history of anger. Standard errors and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for all analyses were estimated with SUDAAN, 31 to adjust for the design effects of complex sample surveys such as the NESARC. Because the combined SE of 2 means (or percents) is always equal to or less than the sum of the standard errors of those 2 means, we conservatively consider that 2 CIs that do not overlap are significantly different from one another.Reference Agresti 32 We consider significant odds ratios those whose CI does not include 1. Two sets of logistic regressions examined associations between anger and lifetime comorbid psychiatric disorders while adjusting for potential confounders. The first set adjusted only for sociodemographic characteristics that differed between individuals with and without a lifetime history of anger. The second set further adjusted for the presence of other comorbid psychiatric disorders to identify common and unique factors underlying the associations of comorbid disorders with anger.

Because only minor differences were found between the model that adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics, and the model also adjusted for other comorbid disorders, results are shown for the unadjusted models and the model that adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics and comorbid psychiatric disorders. Results of the set that adjusted only for sociodemographic characteristics are available from the authors upon request.

Findings

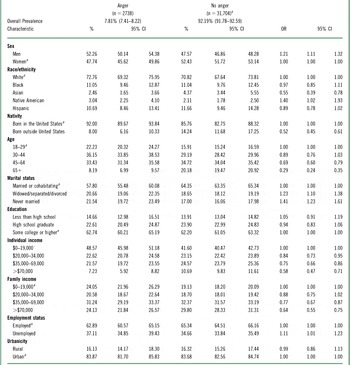

Sociodemographic and socioeconomic characteristics

The overall lifetime prevalence of anger in the general population was estimated to be 7.81%. The odds of anger were significantly higher in men than in women. The odds of anger were significantly lower in Asians than in Whites. On the other hand, Native Americans had higher odds of anger than Whites. The odds of anger were lower for individuals who were foreign-born, older than 45 years, or had individual or family incomes greater than $20,000 and $35,000, respectively. The odds of anger were significantly higher in individuals who were widowed, separated, divorced, or never married, as well as those who were unemployed (Table 1).

Table 1 Sociodemographic characteristics of individuals with and without anger in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions

a Reference group.

OR = odds ratio, CI = confidence interval.

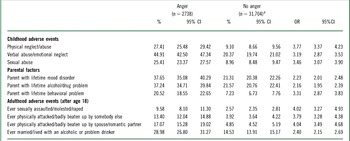

Life events and risk markers

The odds of all childhood adverse events, parental factors, and adulthood adverse events were significantly higher among individuals with anger. Physical abuse and neglect, having a parental history of behavioral problems, and having been physically attacked or badly beaten by a spouse or romantic partner after age 18 were correlated with the greater odds of anger (Table 2).

Table 2 Life events and risk markers of individuals with and without anger

a Reference group.

OR = odds ratio, CI = confidence interval.

Psychiatric disorders and psychosocial functioning

A significantly larger percentage of individuals with (87.16%) than without (39.55%) anger met criteria for at least one psychiatric disorder in the past 12 months. The odds of all Axis I disorders were significantly higher in individuals with anger than in individuals without anger (Table 3).

Table 3 Past 12-month psychiatric comorbidity, overall health, substance use, and level of disability for individuals with or without anger

a Reference group.

b Adjusted by sociodemographic characteristics and Axis I and II comorbidity. Additional odds ratios (OR) estimated in logistic regressions adjusting only for sociodemographic characteristics are available on request (see text in Methods section).

c Assessed on a lifetime basis.

d Assessed during the last month.

OR = odds ratio, AOR = adjusted odds ratio, CI = confidence interval, SF-12 = Short Form 12v2.

Among Axis I disorders, the highest ORs were for bipolar disorder, drug dependence, and psychotic disorder. The odds of all personality disorders were also significantly higher in individuals with anger. Among personality disorders, the highest ORs were for borderline, schizotypal, narcissistic, and dependent personality disorder. Individuals with anger were significantly more likely than individuals without anger to use drugs, alcohol, and tobacco.

Anger was significantly associated with lower mental and physical component summary scores in the SF-12.

Logistic regressions adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics and Axis I and II disorders

After adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics and the presence of comorbid Axis I and II disorders, the odds of Axis I disorders among individuals with anger remained significant, except for nicotine dependence, alcohol abuse, drug use disorders, dysthymia, panic disorder, and social anxiety disorder, which no longer significantly differed between the groups. The odds of having schizotypal, narcissistic, borderline, and histrionic personality disorder remained significantly higher, while dependent and schizoid personality disorders became significantly lower in individuals with anger. The odds of using tobacco in the past 12 months also became significantly lower in individuals without anger.

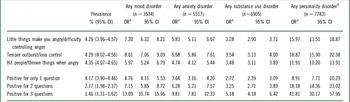

Prevalence of psychiatric disorders by question and anger severity

The prevalence of “anger that was difficult to control/brought up by little things” was 4.26%, the prevalence for “temper outburst/anger loss control” was 4.29%, and for “hitting people/throwing things when angry” was 4.35%. Across all respondents, 4.17% answered positively to 1 anger question, 2.17% to 2 anger questions, and 1.46% to all 3 questions.

Answering positively to any of the 3 questions was significantly associated with personality, mood, anxiety, or substance use disorders (Table 4). Responding positively to the question on temper outbursts and loss of control was associated with the greatest odds of having any mood, anxiety, and personality disorder. There was a dose-response relationship, with the odds for any of the psychiatric disorders increasing with the number of positively answered anger questions. The highest odds when answering positively to the 3 questions was for personality disorders followed by mood and anxiety disorders.

Table 4 Twelve-month prevalence of psychiatric disorders by anger severity

a Unadjusted ORs.

b Assessed on a lifetime basis.

OR = odds ratio, CI = confidence interval.

Discussion

A history of inappropriate, intense, or poorly controlled anger that interferes with work, school, or social relations is found in roughly 1 in 13 U.S. adults. This type of anger was especially common among men and younger adults, and was associated with high rates of childhood adverse events, a wide range of current psychiatric disorders, and diminished psychosocial functioning.

Men were more likely than women to report anger. Our findings on higher rates of anger in men parallel those of studies showing gender differences in aggression in the community.Reference Eaton, Kann and Kinchen 33 Higher social permissiveness toward aggressive behavior in men may also contribute to increased rates of expression of anger in men.Reference Potegal and Archer 34 Studies on gender differences in emotion expression suggest that males tend to express more externalizing emotions such as anger, and that the modulation of these expressions during childhood facilitates the development of assertiveness, persistence, and self-efficacy.Reference Chaplin and Aldao 35 At the same time, however, a greater tendency to express externalizing emotions instead of other emotions such as fear might contribute to males’ greater risk for conduct problems.Reference Chaplin and Aldao 35 Our study also found ethnic differences in the prevalence of anger. This is consistent with a meta-analysis that found cultural differences in anger recognition,Reference Elfenbein and Ambady 36 suggesting that although emotions are likely universal, the process of learning to control both their expression and perception is highly dependent on cultural factors and specific values about emotion and emotion control.Reference Mauss, Butler, Roberts and Chu 37

Anger was inversely related to age. With age, adults consistently report less negative affective emotions.Reference Charles, Reynolds and Gatz 38 Older adults are less likely to experience anger, and, when they do so, it is usually experienced with a lower intensity.Reference Schieman 39 Older adults may be more effective at regulating emotions and therefore experience fewer and less enduring negative emotions, as they manage and focus on their emotions better than young adults and adolescents.Reference Brassen, Gamer, Peters, Gluth and Büchel 40 Older adults can draw on accumulated experiences and use a larger repertoire of strategies when encountering emotionally charged problems. In relation to younger adults, older adults may more commonly rely on passive emotion–focused strategies such as avoidance and passive-dependence, which may help maintain less activated levels of arousal.Reference Blanchard-Fields, Mienaltowski and Seay 41

Anger was strongly associated with a broad range of life events, especially a history of childhood physical abuse and neglect. Childhood traumatic events that pose an actual or perceived threat can activate extreme stress responses.Reference Ouellet-Morin, Danese and Bowes 42 , Reference Heim, Newport and Heit 43 Brief increases in cortisol during stress initially increase alertness, activity levels, and feelings of well-being. However, prolonged elevations stimulate withdrawal, dysphoria, and feelings of tiredness. Persistent activation of stress-response systems, greater intensity, and prolonged traumatic events appear to induce changes in arousal systems and to be linked to the release endogenous opioids and the predisposition to emotional dysregulation.Reference Kennedy, Koeppe, Young and Zubieta 44 The widely documented association between psychiatric disorders and childhood trauma may also help explain the high rates of anger in these individuals.Reference Dong, Giles and Felitti 25 , Reference Herrenkohl, Klika, Herrenkohl, Russo and Dee 45 – Reference Pérez-Fuentes, Olfson and Villegas 48 In addition to links between adverse childhood events and anger, adulthood adversities such as having been married to or having lived with a partner with an alcohol use disorder were also strongly associated with inappropriate, intense, or poorly controlled anger.

Inappropriate, intense, or poorly controlled anger was associated with a wide range of psychiatric disorders. Borderline personality disorder, with its characteristic and persistent disturbance in impulse control, affect regulation, and interpersonal relations, was the most strongly associated with anger. Anger was also strongly related to all other assessed personality disorders. It was also highly prevalent among individuals with bipolar disorder, a disorder that is marked by affective instability, impulsivity, and interpersonal problems.

Considering the cross-sectional design and retrospective nature of studies of this kind, this assessment does not permit causal inferences. It is, therefore, also possible that individuals with psychiatric disorders experience several adverse psychosocial consequences that predispose them to inappropriate, intense, or poorly controlled anger. Adults with psychiatric disorders are often socially isolated due to personal attributes, such as fear of victimization, odd behavior, and underdeveloped social skills. Larger societal forces including stigma and negative stereotyping may compound social isolationReference Ware, Hopper, Tugenberg, Dickey and Fisher 49 and prompt anger. Lack of social skills, higher rates of unemployment, and other disadvantages may further reduce opportunities of individuals with psychiatric disorders to engage in reciprocal social activities. Hostility may sometimes be a response from negative interpersonal experiences, but can also lead to negative responses in future social interactions. Hostile cognitions can lead individuals to experience and generate interpersonal stressors with self-perpetuating cycles in which hostile thoughts are confirmed and reinforced through ongoing negative interpersonal interactions.

Inappropriate, intense, or poorly controlled anger could also be a consequence of the neurobiologic abnormalities underpinning particular disorders. This type of anger may serve as an indicator or the expression of frontolimbic dysfunction commonly found in several psychiatric disorders.Reference Tromp, Grupe and Oathes 50 , Reference Minzenberg, Fan, New, Tang and Siever 51 Developmental alterations in prefrontal-subcortical circuitry as well as neuromodulator abnormalities may play an etiologic role. Imbalances between limbic impulses and prefrontal control mechanisms appear to be important in a range of psychiatric pathology provoked by negative stimulation, including externally directed aggression as well as withdrawal behaviors associated with borderline personality disorders, antisocial subjects, PTSD, and mood disorders.Reference Matsuo, Glahn and Peluso 52 – Reference Hazlett, New and Newmark 54

A dose-response relationship appears to exist between extent of anger and risk for a broad range of psychopathology. Whereas mild forms may present in larger segments of the population, more severe forms of anger appear to be especially strongly associated with psychiatric disorders. Alternatively, higher levels of anger may represent a marker of risk for these disorders. A small proportion of individuals with anger problems receive treatment specifically for their anger.Reference Vecchio and O'Leary 55 As evidenced by our study, the vast majority of individuals with anger have a current psychiatric disorder, which could increase the complexity of cases presenting to treatment. Although anger appears to be more common than many psychiatric symptoms commonly explored by clinicians, it might often go undetected. By assessing anger problems, clinicians may be able to increase recognition and treatment of psychiatric disorders and to improve their protracted course and management. Meta-analysis supports the implementation of cognitive therapies to target anger specifically,Reference Vecchio and O'Leary 55 and other studies show that early improvement in symptoms of anger predicts response and remission in individuals with major depression, suggesting that monitoring of anger symptoms could help guide treatment.Reference Farabaugh, Sonawalla and Johnson 56 For example, in a recent study of 676 veterans who served in Iraq and Afghanistan, difficulties managing anger were associated with post-deployment PTSD hyperarousal symptoms.Reference Elbogen, Wagner and Fuller 57 These results suggested that assessment of risk factors for anger in veterans may identify those at risk of problematic post-deployment adjustment.

Our study has several limitations. First, information on anger was based on self-report and not confirmed by collateral informants, leading to possible misclassification. Second, because the NESARC sample only included persons in civilian households and those in group quarters who were 18 years and older, information was unavailable on adolescents or individuals in prison who may have a higher prevalence of anger. The unique issues and needs of these groups might differ from those of general population adults. Given the importance of this problem, this calls for appropriate investigations of these excluded groups in other studies. Third, to minimize subject burden, the assessment of anger was based on 3 questions from the AUDADIS-IV, rather than using longer, more clinically based scales or better validated psychological assessments of anger.Reference Novaco 58 , Reference Spielberger 59

Nonetheless, the 3 items showed good internal consistency. Even with this broad definition, the results of the study suggest that anger that was reported as “troubling or causing them problems at work or school, with their family or other people” is strongly associated with high rates of psychopathology, supporting not only its face validity but its clinical relevance. Fourth, participants may have underreported anger, due to concerns of social desirability. However, previous studies with the NESARC have reported even higher rates of other socially undesirable attributes such as shopliftingReference Blanco, Grant and Petry 60 or firesetting,Reference Blanco, Alegria and Petry 61 domestic violence, and commission of illegal acts,Reference Alegria, Blanco and Petry 62 – Reference Goldstein and Grant 64 suggesting that underreporting of anger, if present, is unlikely to be substantial. Despite these limitations, the NESARC provides detailed, nationally representative survey data on anger and its correlates.

Conclusions

Anger is relatively common and is associated with high rates of psychopathology, lifetime history of traumatic events, and psychosocial impairment. As we move to a better scientific understanding of its prevalence and distribution in the population, the development of effective screening tools and early intervention strategies for individuals with anger may benefit a large segment of the general population, especially young adults.

Disclosures

Mayumi Okuda does not have anything to disclose. Julia Picazo does not have anything to disclose. Mark Olfson has the following disclosure: Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality, Grant U18 HS021112, research support. Deborah Hasin has the following disclosures: NIAAA, Grant (K05 AA014223), grant recipient; NIAAA, Grant (U01 AA018111), grant recipient; New York State Psychiatric Institute, employee, salary. Shang-Min Liu does not have anything to disclose. Silvia Bernardi has the following disclosure: NIMH, Grant R25:MH086466, grant recipient. Carlos Blanco has the following disclosures: NIH, Grant MH82773, grant recipient; NIH, Grant MH076051, grant recipient; NIDA, Grant DA019606, grant recipient; NIDA, Grant DA023200, grant recipient; National Cancer Institute, Grant CA133050, grant recipient; NYSPI, employee, salary.