1. Introduction

The aim of this paper is to show how common property systems in peasant communities in different African contexts not only provided access to vital resources and distributed these via locally devised institutions but that these were also vital for resilience. The paper uses peasant theories in social anthropology and research data from eight case studies in three ecozones, such as drylands (Morocco, Ghana), semi-arid areas (Sierra Leone, Malawi, Tanzania) and wetlands (Cameroon, Kenya, Zambia), to develop and test nine resilience variables. These are further illustrated in exemplary case studies, one case each in drylands (Morocco), semi-arid areas (Sierra Leone) and wetlands (Zambia) in order to show how the link between access to the commons and resilience was structured and embedded in power, economic and religious relations, which were part of common property institutions. The development and maintenance of these structures were put under pressure during colonial times, and extensively so during postcolonial times, but mainly after structural adjustment programs,Footnote 1 which raised the interest in land and reduced the importance of the land-related common-pool resources (pastures, wildlife, fisheries, water, forestry and non-timber forest products).Footnote 2 The issue of resilience is of importance here as the lack of access to, and local governance of, these resources undermine the capacity to recover after economic crisis. This paper shows that communal property rights – and thus collective access rights to resources – are massively reduced when such areas become valuable. In such cases collective ownership of resource areas of peasants and thus their use is contested by state and corporate companies who promise to bring development when removing them from collective owners. The argument of the paper is that there is a lack of understanding of how important peasant subsistence production is for resilience and that this also leads to an underestimation of the externalities of the land grabbing processes. To strengthen the argument, data from longitudinal social anthropological case studies are used and discussed with a historical perspective regarding issues of resilience in four time periods. The first period refers to what is labelled for this paper ‘precolonial’ (fifteenth to nineteenth century). This means that for the African cases discussed here, the European colonial powers only had a marginal impact on local resource governance as these territories were not yet under European territorial control. The development of local common property institutions by which resources were managed falls into this period. The second period is the era of colonial territorial control beginning with the Berlin Conference in 1884 and ending with the independence of these states that was mostly finalised by 1965. During these periods the case study areas were colonialised mainly by the UK and France claiming colonial state property and centralised legal arrangements for all resources and differing in their governance (indirect and more direct rule, respectively).Footnote 3 Thirdly, the period after independence and postcolonial state development, during which new state elites established state rule often based on previous colonial boundaries and legal frameworks (1970s–1990s). The fourth and last period relates to the crisis of state development due to debts and structural adjustments and the adoption of a neo-liberal economic order, including processes of privatisation. This phase reached a peak in 2008, when many of the areas of this study became interesting for external investment in land. The first three periods provide the basis for understanding contemporary changes in the neo-liberal global capitalistic and state policies providing further ground for large-scale land acquisitions (LSLAs) that contribute greatly to land, or more precisely, commons, grabbing, a process that leads to a reduced capacity of peasant groups to be resilient.Footnote 4 These data are then compiled for comparative purposes in Tables 1-3 together with the data of the illustrative cases.

Based on theoretical reflections, nine variables are deduced and explained to qualitatively assess resilience in three ecozones (drylands, semi-arid and wetlands) during the four periods.

The paper is structured as follows. It first gives a short overview of the qualitative methods used in these social anthropology case studies and their relation to historical research, before discussing theory on resource governance and resilience in anthropology. Based on these approaches, the paper shows what variables can be taken to assess resilience in the four periods in the three ecozones (drylands, semi-arid and wetlands). The following section deals with assessing historically important background information on the African context during the first three periods mentioned above (precolonial, colonial, postcolonial periods) before discussing general aspects of the final fourth neo-liberal-LSLA period, showing how land grabbing leads to issues of commons and resilience grabbing. As mentioned above and due to text limitations, only one case of each ecozone is used for more detailed illustration (drylands: Morocco; semi-arid areas: Sierra Leone; and wetlands: Zambia). The results regarding other examples of the respective ecozones (drylands: Ghana; semi-arid areas: Tanzania and Malawi, wetlands: Kenya and Cameroon) and the discussion of the resilience variables are additionally included in Tables 1-3, summarising the three first-time phases related to the case studies. The respective table for the fourth period (neo-liberal), giving an overview of all eight case studies, is then presented in the discussion section of this paper. Finally, the results are discussed, and a conclusion is drawn regarding the question of how commons grabbing is related to resilience grabbing.

Methodologically, this paper is based on a novel approach to combine and systematically compare anthropological case studies, conducted at the institutes of social anthropology in Zurich and Bern over the last 15 years, in the context of different research projects mainly funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF). A social-anthropological, qualitative database was obtained through extensive fieldwork, using participant observation as well as different interview techniques (including open, semi-structured and structured interviews, focus groups and biographies based on oral history). Until now, these case studies have never been compared and systematically analysed to find the root causes of resilience or vulnerability over such a long-time frame. While parts of the anthropological case studies have already been published by individual members of our research groups, thanks to the combination of these qualitative data sets new insights and patterns to understand peasant resilience are deduced and discussed here for the first time. This is done by using a historical approach recognizing four periods (precolonial, colonial, postcolonial and neo-liberal) and discussing path-dependent changes in property rights institutions and resource governance in three different ecozones and cultural landscapes (drylands, semi-arid areas and wetlands). To date, there is no other encompassing work on how to differentiate resilience variables among peasant societies or a discussion, based on a larger set of empirical qualitative case studies, on how these historical changes impact the capability to recover after major economic and environmental crises in a comparative way in three different ecozones.

2. Peasant theories and the issue of resilience in social anthropology

Cancian provides a summary of studies of farming societies in social anthropology.Footnote 5 Within these, groups and local communities only partially embedded in state contexts developed strategies for adapting to natural as well as political environmental constellations often a long time before state control. These refer to a set of specific strategies that are designed to cope with insecurity and political instability and range from intensive (low mobility) to extensive (high mobility). Despite this variability, such peasant communities share a basic strategy as they have to balance between the utility of production for subsistence on the one hand and the drudgery of the workload itself on the other. This model developed by Alexander Chayanov, a Russian agronomist working in the 1920s, showed that peasants only work as much land and produce as many crops as necessary to meet the demands for feeding the family. An overproduction is not rational as it exceeds the work required for the needs.Footnote 6 However, this broad approach that was picked up on by peasant studies in the 1960s needs to be combined with a second model,Footnote 7 which argues that actors in all peasant societies need to include risk in their economic calculations. This means that in the ‘game against nature’, peasants must work more and accept the drudgery to diversify production in order to cope with the risks of poor yields or complete crop failure. Thus, not the best possible yield but the most secure yield is what peasants try to achieve. This so-called ‘minimax strategy’ (maximizing minimal returns or minimizing maximum loss) model is also related to what Sahlins and Meillassoux called the domestic mode of production and can be closely linked to the governance of common-pool resources in common property institutions.Footnote 8 In all eight case studies the common-pool resources (CPRs) were managed by common property institutions. It must be emphasised that this debate on how to reduce risk or to transfer uncertainty into risk assessments has appeared in peasant literature in social anthropology in the past but has rarely been used in actual debates.Footnote 9 Netting was one of the first anthropologists to focus not just on private property in agrarian studies but also on the linking of common property tenure institutions with peasant communities.Footnote 10 In contrast to the idea of the tragedy of the commons, Netting showed that peasants in the Swiss Alps shared common-pool resources in a sustainable way and for that purpose devised institutions to govern high Alpine pastures, forestry and water.Footnote 11 Balancing on an Alp Footnote 12 illustrated that perspective nicely: peasant economics is about balancing subsistence production, not with a profit or gain perspective but with a multifaceted perspective that combines private and communal property. Cooperation is needed to access water, produce fodder for the winter and to cope with the high workload in forestry. Such cooperation and coordination require institutions to reduce transaction costs (information about membership, monitoring and sanctioning) in a way to reduce transaction costs over the long term. This was exactly what interested Elinor Ostrom and was used by her for the development of principles for robust institutions.Footnote 13 These institutions are in fact the ‘holy grail’ for the resilience of peasants as will be shown further. In Netting's Smallholders, Householders he shows how smallholder peasants are vital producers and that they have the capacity to resist shocks.Footnote 14

However, anthropologists later began to take a closer look at issues of power and institutional change: rules and regulations are not developed by everybody but need to incorporate power differences (for example pastoralists, especially in African contexts). The particularly interesting work of Ensminger, later modified by Haller, expands that critique to focus on questions of stability and resilience when institutional settings change, which can lead to the undermining of resilience. Ensminger argues that environmental, demographic and technological change can modify the relative value of an area and this process has an impact on local constellations in relation to the bargaining power of local actors among themselves and between them and others coming from outside the community and further leads to institutional changes. For example, if the value of agricultural land increases due to increasing land prices for innovations or investments, some local actors with high bargaining power might profit but many other actors, being collective owners or users of commonly owned land-related resources (pasture, water, fisheries, wildlife), lose their bargaining power as the land-related common-pool resources no longer have value. Therefore, exclusionary processes take place and lead to a new institutional setting (privatisation of land and later possibly water or other resources as well, sometimes based on state laws and regulations). This institutional choice (also known as ‘institution shopping’) is further legitimised ideologically by using narratives of underdevelopmentFootnote 15 and discourses of development (promises of being able to find jobs, leading a better life, new infrastructure options).Footnote 16

What often remains undebated in this model are two elements that are important for resilience: first, the power to value an area or a resource on the land – mostly common-pool resources ‒ as being of no importance and not of value; and second, that it is ‘pure nature’ (with no owner and user) to be appropriated.Footnote 17 However, these political, discursive and ontological power sources are undermine vital resources for commoners. An approach combining new institutionalism and political ecology, as it has been proposed for commons analysis in the global south,Footnote 18 could help to address issues of the three power sources and their impact on peasant resilience. This combined New Institutional Political Ecology (NIPE) model helps in analysing the transformation. Thus, the question must be asked as to how transformation processes in actual contexts affect the vulnerability and resilience of these commoners' organisations.Footnote 19

The issue is now how resilience unfolds in such contexts: resilience is understood as ‘the capacity of a system to absorb disturbance and reorganise while undergoing change so as to still retain essentially the same function, structure, and feedbacks and therefore identity’.Footnote 20 This means that such local organisations were able to adapt and transform themselves in a way that kept their basic structures and way of acting. This, however, does not exclude the fact that transformations involve shifts in perception and meaning, social network configurations, patterns of interactions among actors including leadership and political and power relations, and associated organisational and institutional arrangements.Footnote 21 Such shifts and new arrangements – as will be shown ‒ were the focus of the research used for this paper and the corresponding results. For this work, resilience is defined as both an outcome, especially when linked to an improved adaptive capacity of communities, and a process linked to dynamic changes over time associated with community learning and the willingness of communities to take responsibility for, and control of, their development pathways. Despite their ability to adapt and transform themselves, collective systems as institutional forms have always been under pressure from the outside and the inside.Footnote 22

Such factors become particularly important when dealing with interlinkages between internal and external actors, especially when it comes to state or investments of transnational companies. There are gender and class power asymmetries in common property systems, even if they might be weaker than in private property systems, in which the most powerful are more able than others to shape the rules of the game. An institutional and political-ecological analysis reflects these processes and their impact on commons and their resilience. Social-ecological resilience would then mean, under a political ecology and new institutionalism perspective, that the more powerful do not have the ability to override the interests of other, less powerful actors and that less powerful actors have a level of bargaining power so that their views and aspirations cannot be overridden. However, within this context of studies on relatively balanced power constellations, several scholars researching peasant communities have indicated that the following strategies to cope with shocks due to climate, seasonal pests and inter-seasonal changes of conditions, as well as the new need for cash, are of importance. It is also clear that being a commoner of a cultural landscape ecosystem with several resources also offers pathways of diversification.

3. Nine resilience variables derived from anthropological approaches and case studies

Nine essential variables for resilience were identified in the previous section. All of these variables include findings from the eight case studies in addition to the theoretical aspects presented above on minimax strategies, commons institutions and power relations. These variables are listed as follows and explained further below:

A. Community membership,

B. Access rights to land-related common-pool resources,

C. Access including pasture,

D. Mobility between pastures,

E. Co-ownership of water,

F. Options for diversification,

G. Rights to other land-related common-pool resources,

H. Reciprocal arrangements,

I. Storage facilities

3.1 Being a member of a community with access to commons and common property institutions

Membership is key to accessing many of the resources that enhance the diversity of options and reducing the risk of food production or access failures in times of crisis. In all the cases in this paper, membership is an important element of shared ownership and access to the commons often via lineage or clan groups. The cases also show that it is not just access, but also the ability to profit from rules made in the past that regulate and coordinate access rights in times of need for members. Membership is also important from a political ecology perspective because it can reduce the bargaining power of more powerful actors to take all the resources and foster a need for a rightful share. There are also non-members who do not have a share (in the African context, so-called ‘latecomers’); however, our research presented here illustrates that even non-members must be included in forms of sharing in times of need and that it is a levelling of power asymmetries that enhances resilience as it demands sharing and reciprocity as well as enhancing social capital, increasing a help-providing network.Footnote 23

3.2 Availability of, and access rights to, land, water and other common-pool resources

Membership includes rules of access to land and resources on the land in a coordinated way. In Morocco, among Berber groups, availability is linked to rights one has as a clan member, while in Sierra Leone and Zambia as belonging to specific groups, which are said to have arrived in the area during different times. Ownership and access to land alone are insufficient for agriculture or gaining access to other diversified land-related common-pool resources such as water, pasture, wildlife, fisheries, forests and non-timber forest products (NTFPs). People also need access to land-related common-pool resources as these often provide access to necessary sources of protein, vitamins and other nutrients as well as products for construction or sale. All three ecozones show such examples of multiple access rights to land and land-related resources based on membership or relations to people having membership: in the dryland areas, the combination of access for local and external groups to land-related resources; in semi-arid areas, the use of seasonal variability in defining access; in the wetlands, access rights related to in- and out-migration rules. The following resilience variables relate to variable B and clarify it.

3.3 Access including pasture

Pastures are also important for peasants as they can either share this with pastoral groups and profit from reciprocal access or goods or, alongside agricultural production, use domesticated animals, which are important for food as well as for crisis buffering reasons. In dryland areas, such as among Berber communities in Morocco, direct access to pastures for fodder production as well as having pastures to give for regulated use to outside groups for various benefits and payments constituted an important income. In wetlands' seasonal pastures, such as in Zambia among agro-pastoral groups, pasture access and seasonal coordination of access were key elements during times of crisis.

3.4 Mobility rights between pastures

Being mobile to adapt to changes between pastures is central and another precondition for resilience, especially in the context of seasonality. The ability to move between areas is a central element in enhancing resilience as a way to adapt to droughts or an overabundance of water, as can be shown among Berber communities in Morocco and in wetland areas, such as among Zambian agro-pastoral groups, where mobility between pastures is a central issue for keeping cattle alive. This is a central feature of pasture use in drylands to access to pastoral areas that are needed in critical times during the dry season and between seasons. Without such mobility in critical times, access to pastures, while being a right, is not possible and that can mean the end of a herd as a crisis buffer strategy.

3.5 The right to co-own water and have access to it

This is an important feature in dryland areas, and sometimes also in semi-arid areas, as sometimes water, not pasture, can be a critical limiting factor for a herd as well as for additional crop production to buffer a crisis via the availability of water. Access rights to water can again be private or communally organised, but communal access to water often buffers the pressure of water scarcity while common property also enables rules to be set to coordinate access and reduce overuse as in open access or private or badly enforced state constellations. Berbers in Morocco coordinate this use in local communities, depending on seasonality, with diversified access rights. In semi-arid areas, such as among the Temne in Sierra Leone, water availability during the dry season is crucial for agricultural production, while in wetlands water can be over- or underabundant and access is flexible but still coordinated within the seasons, providing the parameters for local rule making, as is shown in the case of Zambian agro-pastoralist groups and water use patterns. The next principle is further linked to access rights to water.

3.6 The option to diversify crop production and to keep a variety of animals for food security and for cash income

Water seems to be a key resource for this variety apart from land and pasture rights, to be able to pursue a minimax strategy regarding the variety of crops as well as a diversity of domesticated animals. In dryland and semi-arid areas, such as in Morocco and Sierra Leone, this option is vital for additional crop production during the dry season for irrigation, and in Morocco for keeping a larger variety of animals than just those adapted to the dry climate. Water makes it possible in dry seasons or dry phases to keep a variety of different domesticated animals rather than just having one species (so not only cows but also goats, sheep, donkeys and camels). After a crisis, smaller and faster reproducing growing animals needing less water and fodder can be exchanged for other animals of higher value, such as cows or other domesticated animals. Owning a variety of animals can also be a source of income in case of catastrophic cash expenditures in the household, such as health, funeral and schooling costs. Water rights also enable the possibility of developing small-scale irrigation and watering gardens.

3.7 Rights to other land-related common-pool resources

In addition to access rights, these include specific institutions regulating access to fisheries, wildlife, forests (timber quotas), and various non-timber forest or other veld products, including ‘hunger foods’ (staples used especially in times of hunger) and medicinal plants. Research in Morocco, Sierra Leone and Zambia showed that there are a large variety of seasonally adapted institutions for these and similar resources such as gathering plants for animal fodder in Morocco, non-timber forest products such as palm fruits and fisheries in Sierra Leone, fisheries, wildlife and also veld products in Zambia. These are classic common-pool resources to which peasant households need access rights in order to cover needs for protein, energy, raw material and means for food shortages and cash.

3.8 Reciprocal arrangements

All these goods might not be available during times of stress within the territory of a local group. However, reciprocal arrangements with a neighbouring group might still provide access rights to these resources for a community or members of a community in need. Such rights exist in Morocco with herding communities, in Sierra Leone regarding access to water and land as well as fisheries, and in Zambia fishing, pasture, as well as hunting rights are also given to outside groups based on the option to also use their resources in times of stress. That means that these arrangements are based on the institutions providing the host community with the right to one's own resources in times of need too. Peasant theories indicate that reciprocity might be an important issue, whether during times of household stress or of community stress as a whole, and also requires social capital (good community and friendship relations).

3.9 Storage facilities and strategies

Storage facilities and strategies are important for storing reserve food linked to resilience through the diversity of storable and non-storable crops as well as the granary technologies of the minimax strategy. Such storage facilities are available in several forms in all the case studies presented in this paper. These facilities are more diversified in drylands, such as Morocco and Sierra Leone, than in the wetlands' cases. Again, these do not just provide food but also sources for cash generation, if needed, as is shown in the case of Morocco, where Berbers store food and keep additional animals for sale, and Sierra Leone, where the Temne also store crops for that purpose, while in Zambia cattle provide a kind of storage of cash as they can be sold in times of need.

These are the resilience variables stemming from a combined assessment of peasant studies' approaches, social anthropology approaches and the empirical findings of the case studies. The variables will then be used for comparative purposes for the eight selected case studies to assess the implementation and importance of these nine variables (Tables 1–3 and Table 4 in the discussion section).

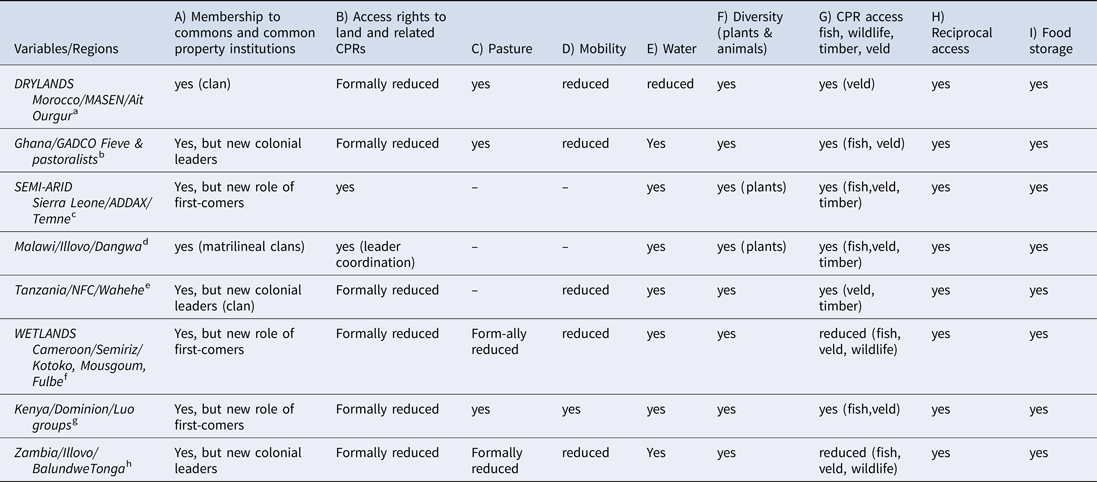

Table 1. Overview variables for precolonial times in main and additional case studies

Sources:

aSarah Ryser, ‘The anti-politics machine of green energy development: the Moroccan solar project in Ouarzazate and its impact on gendered local communities’, Land 8 (2019), 100.

bKristina Lanz, Jean-David Gerber and Tobias Haller, ‘Land grabbing, the state and chiefs: the politics of extending commercial agriculture in Ghana’, Development and Change 49, 6 (2018), 1526–52.

cFranziska Marfurt, Fabian Käser and Samuel Lustenberger, ‘Local perceptions and vertical perspectives of a large scale land acquisition project in northern Sierra Leone’, Homo Oeconomicus 33, 3 (2016), 261–79; Franziska Marfurt, ‘Gendered impacts and coping strategies in the case of a Swiss bioenergy project in Sierra Leone’, in T. Haller et al. eds., The commons in a glocal world: global connections and local responses (London, 2019), 318–35.

dTimothy Adams, Jean-David Gerber, Michèle Amacker and Tobias Haller, ‘Who gains from contract farming? Dependencies, power relations, and institutional change’, The Journal of Peasant Studies 46, 7 (2018), 1435–57.

eD. Gmür, ‘Not affected the same way: gendered outcomes for commons and resilience grabbing by large-scale forest investors in Tanzania’, Land 9, 4 (2020), 122.

gG. Fokou, ‘Tax payments, democracy and rent seeking administrators: common-pool resource management, power relations and conflicts among the Kotoko, Musgum, Fulbe and Arab Choa in the Waza Logone Floodplain (Cameroon)’, in T. Haller ed., Disputing the floodplains: institutional change and the politics of resource management in African floodplains (Leiden, 2010), 121–69; G. Landolt, ‘Lost control, legal pluralism and damming the flood: changing institutions among the Musgum and Kotoko of the village Lahaï in the Waza-Logone floodplain (Cameroon)’, in T. Haller ed., Disputing the floodplains: institutional change and the politics of resource management in African floodplains (Leiden, 2010), 171–93.

hTobias Haller et al., ‘Large-scale land acquisition as commons grabbing: a comparative analysis of six African case studies’, in R. Ludomy Lozny and T. H. McGovern eds., Global perspectives on long term community resource management (New York, 2019), 125–64; T. Haller, The contested floodplain (Lanham, 2013); T. Haller and S. Merten, ‘Crafting our own rules: constitutionality as a bottom-up approach for the development of by-laws in Zambia’, Human Ecology 46, 1 (2018), 3–13.

Tobias Haller, ‘Institution shopping and resilience grabbing: changing scapes and grabbing pastoral commons in African floodplain wetlands’, Conservation and Society 18, 3 (2020), 252–67; Jean-David Gerber and Tobias Haller, ‘The drama of the grabbed commons: anti-politics machine and local responses’, The Journal of Peasant Studies 48, 6 (2021), 1304–27.

Table 2. Overview variables for colonial times in main and additional case studies

Sources:

aRyser, ‘The anti-politics machine of green energy development’.

bLanz, Gerber and Haller, ‘Land grabbing, the state and chiefs’.

cMarfurt, Käser and Lustenberger, ‘Local perceptions and vertical perspectives’; Marfurt, ‘Gendered impacts and coping strategies’.

dAdams, Gerber, Amacker and Haller, ‘Who gains from contract farming?’.

eGmür, ‘Not affected the same way’.

fFokou, ‘Tax payments, democracy and rent seeking administrators’; Landolt, ‘Lost control, legal pluralism and damming the flood’.

gHaller et al., ‘Large-scale land acquisition as commons grabbing’.

hHaller, The contested floodplain; Haller and Merten, ‘Crafting our own rules’.

Further Sources:

Haller, ‘Institution shopping and resilience grabbing’; Gerber and Haller, ‘The drama of the grabbed commons’.

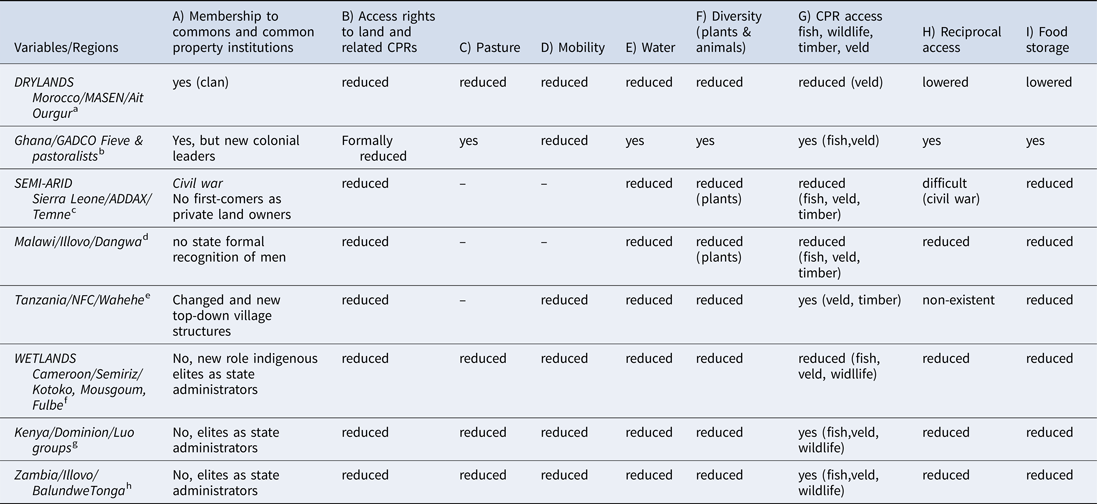

Table 3. Overview variables for postcolonial times in main and additional case studies

Sources:

a Ryser, ‘The anti-politics machine of green energy development’.

b Lanz, Gerber and Haller, ‘Land grabbing, the state and chiefs’.

c Marfurt, Käser and Lustenberger, ‘Local perceptions and vertical perspectives’; Marfurt, ‘Gendered impacts and coping strategies’.

d Adams, Gerber, Amacker and Haller, ‘Who gains from contract farming?’.

e Gmür, ‘Not affected the same way’.

f Fokou, ‘Tax payments, democracy and rent seeking administrators’; Landolt, ‘Lost control, legal pluralism and damming the flood’.

g Haller et al., ‘Large-scale land acquisition as commons grabbing’.

h Haller, The contested floodplain; Haller and Merten, ‘Crafting our own rules’.

Further Sources:

Haller, ‘Institution shopping and resilience grabbing’; Gerber and Haller, ‘The drama of the grabbed commons’.

Table 4. Overview variables for neo-liberal times in main and additional case studies

Sources:

aSarah Ryser, ‘The anti-politics machine of green energy development: the Moroccan solar project in Ouarzazate and its impact on gendered local communities’, Land 8 (2019), 100.

bKristina Lanz, Jean-David Gerber and Tobias Haller, ‘Land grabbing, the state and chiefs: the politics of extending commercial agriculture in Ghana’, Development and Change 49, 6 (2018), 1526–52.

cFranziska Marfurt, Fabian Käser and Samuel Lustenberger, ‘Local perceptions and vertical perspectives of a large scale land acquisition project in northern Sierra Leone’, Homo Oeconomicus 33, 3 (2016), 261–79; Franziska Marfurt, ‘Gendered impacts and coping strategies in the case of a Swiss bioenergy project in Sierra Leone’, in T. Haller et al. eds., The commons in a glocal world: global connections and local responses (London, 2019), 318–35.

dTimothy Adams, Jean-David Gerber, Michèle Amacker and Tobias Haller, ‘Who gains from contract farming? Dependencies, power relations, and institutional change’, The Journal of Peasant Studies 46, 7 (2018), 1435–57.

eD. Gmür, ‘Not affected the same way: gendered outcomes for commons and resilience grabbing by large-scale forest investors in Tanzania’, Land 9, 4 (2020), 122.

fG. Fokou, ‘Tax payments, democracy and rent seeking administrators: common-pool resource management, power relations and conflicts among the Kotoko, Musgum, Fulbe and Arab Choa in the Waza Logone Floodplain (Cameroon)’, in T. Haller ed., Disputing the floodplains: institutional change and the politics of resource management in African floodplains (Leiden, 2010), 121–69; G. Landolt, Lost control, legal pluralism and damming the flood: changing institutions among the Musgum and Kotoko of the village Lahaï in the Waza-Logone floodplain (Cameroon), in T. Haller ed., Disputing the floodplains: institutional change and the politics of resource management in African floodplains (Leiden, 2010), 171–93.

gTobias Haller et al., ‘Large-scale land acquisition as commons grabbing: a comparative analysis of six African case studies’, in R. Ludomy Lozny and T. H. McGovern eds., Global perspectives on long term community resource management (New York, 2019), 125–64.

hT. Haller, The contested floodplain (Lanham, 2013); T. Haller and S. Merten, ‘Crafting our own rules: constitutionality as a bottom-up approach for the development of by-laws in Zambia’, Human Ecology 46, 1 (2018), 3–13.

Further sources: Tobias Haller, ‘Institution shopping and resilience grabbing: changing scapes and grabbing pastoral commons in African floodplain wetlands’, Conservation and Society 18, 3 (2020), 252–67; Jean-David Gerber and Tobias Haller, ‘The drama of the grabbed commons: anti-politics machine and local responses’, The Journal of Peasant Studies 48, 6 (2021), 1304–27.

In the next section, after a short historical introduction that also includes the different local perspectives on environment by local groups and their ontologies, there will be a discussion on how institutional change and commons grabbing through time reduced the availability of these variables for all selected case studies, which then led to resilience grabbing.Footnote 24

4. Shaping the African context of traditional resource governance

Africa has peculiar colonial histories that are also linked to precolonial aspects of Arab and European expansion, which I refer to as the precolonial period, in which European nations did not have territorial control over the areas of the case studies, as indicated in the introduction. These processes are related to slavery and production in the Americas, and transfer of wealth to Europe, fostering industrial innovations and production.Footnote 25 This means that many African subsistence systems adapted not only to ecological features but also to the political environment: many smaller peasant groups had to find the means to defend themselves or find ways to hide to avoid being capture as slaves.Footnote 26 Another issue that has been discussed from religious and other perspectives is what academia and Modern societies call ‘nature’. Many African societies have different forms of pre-Islamic and pre-Christian belief systems in which the main perception is a different ontology and epistemology regarding the environment. Descola stated in general that animist and totemist ontologies are different from the naturalist ontology of capitalist Europe and North America.Footnote 27 This different perception of the environment as containing a spiritual world of souls and ancestral spirits (animism), as well as different hierarchies of spirits and gods (or one god), makes the environment a place full of spiritual actors. Local ontologies can take many forms, as seen in most of the semi-arid and wetlands cases. The common denominator is that spiritual actors have an impact on all things that are important for agrarian production and access to the commons, such as the availability of rain, fertility of soil, crop yields, success in fishing and hunting activities, or mobility to pastoral areas, and also depend on the favour of these spiritual actors. There are many ways of engaging with such spiritual actors that make agricultural production and governance of common-pool resources especially interesting, as outlined in other publications.Footnote 28 The techniques of diversification are broad, as will also be shown later in the examples.

However, if crop yields or success in gaining access to the commons are difficult or weather conditions are extremely poor, many of these local peasant groups see their relationship with the spiritual world as unbalanced. Therefore, seasonal or crisis-specific rituals are needed as well as techniques for consulting oracles to find out which members of the spiritual world local actors are in conflict with, as mainly illustrated in semi-arid and wetland cases. This coherent perception of the spiritual environment as impacting the material world of peasants is also an important element in governing the commons. In many of the groups studied in the following section, institutions also provide access to the commons during seasonal cycles that needs to be coordinated, often using rituals or ritualised activities. As outlined in other works,Footnote 29 ritual activities are helpful for coordination purposes and reduce transaction costs as spiritual punishment can also trigger compliance with local common property institutions for opening and closing the commons, as well as deciding on the inclusion and exclusion of users, and reciprocal resource access arrangements. Most important, such ritualised activities illustrate the fact that from an emic (local) perspective, people perceive their environment as an interlinked cultural landscape ecosystem often related to animist ontologies. It could be summarised as humans not being alone in a local space but related and interconnected with non-human and spiritual beings with which one shares a broader commons than just a human-based one.

The fragmentation of these ontologically various forms of commons management systems by colonial conquest and territorial control (1880–1965) and postcolonial states (1970–1990s), as indicated in the introduction, is key to some of the problems peasants in Africa are facing regarding resilience and is increasingly the case in the context of land and commons grabbing processes. Such grabbing processes are related to path-dependent institutional changes, from systems of common property to state, and later to private property. In state and private property regimes, pasture, fisheries, wildlife and forestry are all managed by separate departments and institutions instead of recognising how these natural resources are mutually dependent and their use needs to be coordinated (considering coherence of laws, regulations, amendments for example). While local institutions in the traditional local systems of common property were inclusive of all resources and their use and were coordinated as having an impact on one another (for instance, fisheries in pastoral areas need to be coordinated with access rules to pastures) as can be shown in all the three ecozones, the new system of fragmented state and private rights is often completely uncoordinated (for example, rules for conservation and fisheries are not compatible and are used incoherently).Footnote 30 Roughly, these can be linked to the following periods indicated above: (a) common property institutions for the governance of common-pool resources evolved in precolonial settings; (b) colonialisation led to institutional change from commons to state property and fragmentation of resource governance; (c) this institutional setting continued under state elites in the postcolonial phases; until (d) the 1990s with state debt crisis and the demand for structural adjustment leading to privatisation processes and the contemporary neo-liberal period Africa is in now. This current period is characterised by private and semi-private investments, leading to an acceleration of commons grabbing processes.Footnote 31

Even more problematic for resilience are two general issues: state property of fisheries, forestry and wildlife as well as pasture often cannot be controlled as state property institutions because the states in charge lack of financial means for monitoring and sanctioning in African contexts – a problem also related to cuts in government budgets due to structural adjustment programmes.Footnote 32 As local common property institutions have also been dismantled, there is a de facto open access from which often external, more powerful actors profit, claiming to be citizens of the state, and therefore – as the state is not present – use a ‘take it all’ mentality, which is then also adopted by local actors (tragedy of open access). This has been called the ‘paradox of the state’, being present and absent at the same time.Footnote 33 Secondly, due to overuse resulting from this paradox, external powerful actors can also try to claim private or conservation rights to these resources (green grabbing for instance), which again excludes local users, especially when protected areas are installed.Footnote 34 But the main issue related to land and commons loss began about 10 to 15 years after the start of the neo-liberal period, in which land was privatised and external and local elites gained access to land legally fragmented from the other land-related common-pool resources. The following section gives a short introduction into the land and commons debate before discussing in more detail different ways of losing the commons and resilience capacity in three selected case studies, with the other cases summarised in Table 4.

5. LSLAs as commons and resilience grabbing in the neo-liberal age

In this section the focus is on the scientific debate on the contemporary period (neo-liberal from 1990s onwards) as it is important to understand the loss of resilience that becomes evident in the case studies: there is wide-ranging literature on what is called the ‘new enclosure’ or the ‘new land rush phenomenon’ as a reaction to the fuel, food and financial crisis since the mid-2000s, as international investors and national elites are acquiring large tracts of land in poorer, mostly African countries.Footnote 35 Following the above-mentioned crises, land represents a safe asset for financial speculators, multinational corporations and local business people alike.Footnote 36 Following cited literature, land grabbing is related to capturing control over land and other resources involving coercion and the power of capitalism. Furthermore, land grabbing is often oriented towards production for the market via forms of extraction.Footnote 37 While there is controversy about the scale of the phenomenon and the issue is very volatile,Footnote 38 data collected by the land matrixFootnote 39 show that commons are involved to a large extent in most of the reported land deals. The colonial period considerably influenced the way large-scale investment takes place today on the African continent because large tracts of land, while being commons before colonial times, were declared to be vacant by colonial governments and placed under the legal authority of the state, meaning they became state property.Footnote 40 Simultaneously, the power of colonially introduced chiefs was strengthened.Footnote 41 Africa's role as a raw material provider also goes back to the colonial period and this is extended in the new discourses on development. Furthermore, as indicated above with reference to Ferguson's Anti-Politics Machine of development related to state institutions (formal laws and regulations for agrarian development and compensations) and ‘new commons’ common-pool initiatives in the form of corporate social responsibility (CSR) programmes.Footnote 42 Furthermore, these strategies are increasingly embedded into neo-liberal ideologies of economic or – since 2015 – green development.Footnote 43 As nicely outlined by Fletcher, this ideology defines development as an economic progress of individual efforts in the market that helps to eradicate poverty based on the institutional selection of private property against other forms of property. Interestingly, the state should be, but is not, absent but creates a well-tuned environment with adapted interferences reducing transaction costs for companies.Footnote 44 Therefore, state actors still profit from these policies, often without involving local actors and actors' groups apart from local elites. State actors and investors promote ideologies of modernity based on discourses of market-oriented economic development including green development based on the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).Footnote 45

One important element of institutional change in the context of commons grabbing is that it profits from previous – and in the age of neo-liberalism ongoing – institutional pluralism. Therefore, commons grabbing processes are also linked to processes of what has been called ‘institution shopping’ by both very powerful and less powerful actors.Footnote 46 Data of several research projects suggest that investments using institutional pluralism related to development not only lead to commons grabbing but also to removing resilience through the grabbing process as compensations are not paid to all members and CSR programmes of corporate social responsibility do not cover the losses.Footnote 47

Drawing from these reflections, this paper now examines African peasants in several contexts during four historical periods outlined above (the precolonial period of the fifteenth to the nineteenth century, the colonial period of 1880–1965, the postcolonial period from 1970–1990, and the neo-liberal period (since the 1990s) and how commons grabbing then leads to the undermining of resilience capacities in the cases compared in this paper. Analysis will then be conducted based on the nine interrelated variables outlined at the beginning of the paper to assess how the investments in the areas of study affect the resilience of African peasants (Tables 1–3).

6. Towards commons grabbing and undermining of resilience

This chapter explains in four subsections related to the four time periods exemplary cases from dryland (Morocco), semi-arid area (Sierra Leone) and wetland (Zambia) institutional and land transformation changes that have an impact on local peasant and pastoral communities during a) precolonial settings in which local common property institutions developed, b) colonialisation and institutional change towards state property, c) postcolonial phases consolidating state property and fragmentation of resources and d) investments and the shaping of commons grabbing in times of neo-liberalism.Footnote 48

6.1 Precolonial period (fifteenth – nineteenth century)

6.1.1 Drylands

In the Atlas dryland mountain region of Ouarzazate in southern Morocco water is scarce and small rivers and adjacent pastures are of central interest to the Berber farming groups. Before colonial times these areas were owned and managed as the common property of clans who regulated access and its timing. Women and poorer groups, including nomadic groups, had access to pasture during the dry season, while people irrigated fields with crops for subsistence in a highly diversified way.Footnote 49

6.1.2 Semi-arid areas

The Temne groups in Sierra Leone are farmers that use common land for rain-fed agriculture and focus on gathering wild fruits, including palm trees, in addition to irrigation of small fields. Access to common-pool resources in commons property is controlled in a clan system of first-comer groups who distribute access to land and water as well as veld products to later-comers. All the groups are organized in male and female secret societies performing monitoring and sanctioning of local rules. Female and male ancestral spirits as well as other different spiritual beings are important for rituals during agricultural production and for access to the commons, which also include reciprocal clan and outside group arrangements.Footnote 50

6.1.3 Wetlands

The Kafue Flats in Zambia are a large floodplain and home to agro-pastoral groups of the Balundwe (Tonga) and Ila as well as fishery groups of the Batwa in the centre of the Kafue floodplain. The area is rich in fish, pasture and wildlife, and local territorial groups organized by ‘big men’ ensure and coordinate access to common-pool resources based on the annual cycle of flood and water receding and common property institutions are adapted to this cycle. By referring to spiritual beings and ancestral spirits the ritual master coordinates access to the commons of fish, pasture and wildlife and this access also includes reciprocal access arrangements between the groups.Footnote 51 Table 1 also shows that for the other cases all the nine elements of resilience are holding with some variations, so that, for example, for semi-arid areas pastures and the issue of mobility related to pasture are not needed or important.

6.2 Colonialisations and institutional change (1880–1965)

During the colonial period, the Spanish and French aimed to control the drylands of Morocco by installing government agents in the common territory used by the Berbers. However, colonial control was not an easy task while the legal notion of state property of land and water was introduced but not fully enforced. But it was a basis on which the postcolonial system of the constitutional monarchy could be built.Footnote 52 Colonialisation in the semi-arid areas was of much greater interest to the colonizers, as were the drylands, as there was more water and fertile land available. In the semi-arid areas of Sierra Leone, communal land rights were legally abandoned and delegated chiefly to local leaders for tax purposes, implying de facto state property, albeit with less enforcement. In the wetlands of Zambia, the British installed new chieftains (replacing the former big men) in the settled areas they were interested in for indirect colonial rule. They further formally fragmented the interrelated cultural landscape and ecosystems into separate uncoordinated systems for the management of land and related common-pool resources (separating the rules for water, fisheries, pastures and wildlife) to exploit local workers. In addition, in this wetland case protected areas were established, which further fragmented access to resources (wildlife, pasture and fisheries) and also reduced mobility between resource areas.Footnote 53 Table 2 summarises the findings of the additional cases and shows that access to many of the resilience-enhancing variables is still operating, although with a reduction in pasture and mobility, and in the last cases in conservation (Zambia and Cameroon as a new case). However, the cultural landscape resources and a formal state ownership are formally separated everywhere with institutional change linked to newly installed leaders or the changing role of leaders as later-owners of the land and common-pool resources.

6.3. Postcolonial period (1970s–1990s)

For all areas the postcolonial period was marked by the transition from the colonial to the new so-called ‘independent state’. While these might look different, it becomes evident that basic structures of the colonial period regarding state structures and governance of resources were often maintained or even strengthened thereafter. Significantly, rights to land and resources continue to be centrally controlled by the state with the tacit support of local elites, as established in the colonial period. The dryland case in Morocco is an example of a constitutional monarchy with a basic centralised state structure following the French model, and control in the Berber areas of Ouarzazate (the Ait Ogour) was shared with a local state official.Footnote 54 The semi-arid area of Sierra Leone was transformed into a capitalist state system and first-comer families became private landowners. However, the country was also heavily affected by civil war, when people could only rely on the commons if they were accessible during these violent and chaotic situations.Footnote 55 In the wetland areas there are cases showing full control over resources by the state in collaboration with local elites stemming from colonial times. In Zambia, governance was delegated to colonially installed chiefs who governed the land and the commons in a neo-traditional style, masking the colonial past.Footnote 56 Wetlands are rich in resources because of higher water availability, and there was ‒ especially in drier periods in the 1970‒1980s – an emerging contestation over water-related common-pool resources, such as rich pastures, fisheries and wildlife. De facto open access to common-pool resources have developed due to weak states without the means to enforce their resource rules, that nevertheless undermined the local rules for coordinated and reciprocal use. These situations then lead to problematic issues of overuse of the commons (water, pastures, wildlife, fisheries and forestry). Combined with the resource demands from people of adjacent drylands, the urban population has increasing interest in monetizing these resources from the hinterlands as there are no jobs and there is a decline in relative prices from the export of products (such as coffee, cotton, mining products) from the countries in the case study. The commodification of common-pool resources increases reducing access for local actors and produces tragedies of open access.Footnote 57 This is the case in all areas studied but is also pertinent in the wetland areas. Also important is that new attempts were made in this period to introduce large-scale development irrigation schemes in Zambia with large dams for the Kafue River.

Table 3 provides the following comparable picture: everywhere the notion of common property (variable A) is leading to de facto control by the elites who received more power since the colonial period (with the exception of Morocco still maintaining clan structures). This does not lead to a full exclusion from the commons but to a reduction, depending on whether these common-pool resources can be commodified and are needed by the elites, a fact that becomes more tangible in the final period of neo-liberal order. However, common-pool resources often face de facto open access constellations due to changes in relative prices and due to weak states that undermined local rules, leading to the paradox of the state being present and absent at the same time and resulting in de facto open access or access for only the most powerful. For a summary of the other cases see Table 3.

6.4. Neo-liberal period with investments and the shaping of commons grabbing (1990s onwards)

As the economic situation did not improve after the 1990s crisis in all of the case area countries, all of them had to face structural adjustment programs. These programs also contributed to the opening of the land market as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) dictated adjustments to cut costs and attract investment based on changes in land rights with privatization of land and/or long-term leasehold titles. These institutional changes towards privatization have unfolded since 2008 but already had roots in earlier state-based investment that become exacerbated as relative prices for land and agricultural products increase and green energy issues arise. This process is further exacerbated by private companies that buy land based on the privatisation of land tenure or in partnerships with the state. Many of these land deals seem to be fair but often are not when examined later. Most deals come with some arrangements forced by the state or are linked to local elites, who sell the commons.

In the dryland areas of Morocco, the parastatal company MASEN bought land from the Berber clan Ait Ougur officially to install one of the biggest solar energy fields in Africa on the clan's commons of 3,000 ha. However, not all clan and village groups have signed the agreement. Moreover, women as well as pastoral groups have been excluded from the deal, due to local government officials profiting from it. The payment is sent to a state-controlled account and local people are told to propose projects, which are, however, not considered when they do so. In addition, corporate social responsibility projects are not adapted to local needs.Footnote 58 In the semi-arid areas of Sierra Leone, the Swiss company ADDAX had invested in sugar cane production for ethanol production. Authorized by the government, ADDAX made deals with the so-called ‘first-comers’ only, who are now labelled as private landowners of the former commons, excluding other groups from the deal, and taking large tracts of land and water. For many groups – first as well as late-comers – this means exclusion from access to land and water (including for irrigation), and veld products gives access to cash. While promising compensation and jobs for everybody, the former common land and its resources are removed from local users while few jobs and no compensations were given to local communities except to a few leaders.Footnote 59 While the company did not survive the Ebola crisis (between 2014 and 2016),Footnote 60 the commons grabbing process continues as ADDAX has now been replaced by a Chinese company.Footnote 61 Regarding the wetlands, in Zambia a sugar cane plantation in the area of Mazabuka was extended into the pastoral land of the Balundwe by the major sugar exporting parastatal company Zambia Sugar. One of the reasons for this extension was the full privatisation of the parastatal company as it was sold to the transnational company Illovo Sugar in 2010. The sugar cane plantation extension was based on the implementation of an outgrower scheme partially funded by the European Union. This scheme was based on dubious deals in which farmers gave away plots on which sugar cane was cultivated by the company and the benefit was paid to the farmers with costs deducted. As Matenga shows,Footnote 62 all households do not profit from these schemes as not everybody has land in the area where agro-industrial production takes place (so called ‘blocks’) and the whole process leads to land concentration within the area in which a so-called ‘collective land rights scheme’ is managed by an association, which faces allegations of corruption. While many are excluded, and women in particular lose most,Footnote 63 many outgrowers complain about the rising cost of the partner company of Illovo running the scheme and the lowering benefits for them.

7. Discussion and conclusion

First, all areas were cultural landscape ecosystems managed by locally different common property regimes, some of them segmentary or more hierarchical politically. Nevertheless, members of clan or ethnic groups had access rights as members of these groups and there were clear and at the same time seasonal and ecosystem-related flexible rules for use of the commons. As in most cases, the colonial state took over the tenure rights via institutional change (from common to state property). Consequently, access to land and with the land interrelated common-pool resources became difficult because, after the investment phase following structural adjustments and privatisation with subsequent investments, large tracks of land and resources were removed from previous commoners.

Table 4 gives an overview of what these changes and related losses of the commons means for peasant resilience. This paper identified variables that are important for African peasant resilience against shocks, such as climate, pests, flood or other disasters. These variables are now listed in the table to show whether the investments affect these elements, meaning reducing the possibility of using these strategies or resources to be resilient in the case of a shock. These are as seen in the table as a loss of common property, based on institutional changes that effected in a much earlier period that are linked to the lack of compensations paid to the majority of commoners. The latter claim might trigger criticisms but the case studies reveal that whether the majority of the common population or only the elites have received compensation needs to be assessed. Table 4 indicates that compensation was only paid to elites or only to men, and not to women or larger and marginal groups, especially not pastoralists related to peasants. With the loss of common property people also lose membership in the community and thus social capital vital for resilience. Furthermore, grabbing the commons leads to loss of access to land for direct cultivation, loss of access to pasture, and are further related to a loss of mobility for some groups, which is important (local people owning livestock and pastoralists). Loss of access to water is also very important as it contributes to a further reduction of the capacity to diversify crop production or to keep more domesticated animals, which again is both essential for storage and cash facility reasons. Furthermore, and very importantly, access to fish, wildlife, forestry, food storage, mobility and reciprocal use of common-pool resources all help to provide access to resources in the case of seasonal or inter-seasonal crisis. If this access is lost, resilience is severely undermined.

The result from the qualitative overview regarding the negative impacts of large-scale land investment-induced commons grabbing on resilience is obvious: there is a loss of resilience capacity regarding all traditional strategy variables that did enhance resilience in the past. Only regarding compensations is there a small benefit for local elites. Differences in the case studies only regard the loss of pastures, which seems to be less problematic in semi-arid areas in our cases as there seem to be fewer pastoral people, while in drylands and wetland areas pastoral groups are important as they use both drylands and wetlands during the dry seasons for their animals while peasants might also profit from trade relations.Footnote 64 Despite these differentiations, this study shows that when detailed resilience variables are considered, there is a great loss of overall resilience for all the eight cases in three ecozones studied, especially during the final neo-liberal period. Although this is a finding not yet extended over a larger set of empirical studies, it indicates that resilience grabbing is not a singular but a structural effect of land grabbing as commons grabbing from peasant communities. Furthermore, it also shows that this process has its roots in a path-dependent historical development since the colonial period.

One could argue that these losses of resilience capacities of the commons in all these cases are replaced by new job development or by benefits from corporate social responsibility (CSR) programs. However, research in all the cases show that it is only elites and not former commoners, and especially not less powerful women, who profit. Often compensation is poor, few people are employed, usually only for the short term, and the programs are not developed with participation of or focus on local interests. Therefore, the loss of the old commons is not replaced by ‘new commons’ providing collective development.Footnote 65 However, this study shows more clearly that while the elites profit from the changes, their gains undermine the resilience of most other local inhabitants as elites can harness gains from the institutional changes and have the power to profit from the new tenure constellations. They then are also not as dependent on the commons as the rest of the local actors.

Furthermore, the commons and therefore resilience grabbing also has led to violent conflicts.Footnote 66 In the three ecozones these range from direct violent clashes between peasants and pastoral groups (Ghana, but also Cameroon) to internal conflicts within groups (Zambia, Sierra Leone, Kenya) or within communities and households (Morocco, Tanzania, Malawi, Kenya).

Finally, how local former commoners react to these grabbing processes is also interesting. Our survey shows that strategies might range from ‘weapons of the weak’ (Morocco, Malawi, Tanzania) to more legal and coordinated actions against local elites (Ghana, Zambia, Sierra Leone) and the state as well as the corporations by also using or threatening to use violence (Ghana, Zambia, Cameroon). Therefore, there is not a tragedy of the grabbed commons and subsequent resilience grabbing, but rather a drama of the grabbed commons, which includes local strategies ranging from weapons of the weak to resistance via mobilisation and legal actions, which could become a potential ‘politics machine’.Footnote 67 However, this paper also shows that when the impact of investments is commons grabbing, then this investment also undermines and often removes the resilience of African peasants in the cases studied. A serious aspect requiring further consideration is the way losing common property also means both processes of local exclusions from access to resources and losing social capital resilience stemming from social networks as peasant households increasingly fall into economic crisis, unable to use resources to reinforce social networks. Losing common property also means losing opportunities to continue being – or newly entering – into reciprocal relations within and between groups, which leads to local emic perceptions of resilience loss causing poverty and hunger.Footnote 68 Furthermore, as new issues of cash needs become vital for all levels of everyday livelihoods, women in particular face an increased reproductive workload with lower returns if they are excluded from the commons and the financial gains that would enable them to stabilise resilience.Footnote 69 The novelty of this paper is that it shows historically how such crisis constellations developed in similar ways despite regional differences and how these unfold in relation to institutional change and loss of resilience.