Childhood adversities such as parental divorce, witnessing intimate partner violence (IPV), parental mental illness, and maltreatment (e.g., sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional abuse, or neglect) occur quite frequently and are increasingly being recognized as detrimental to both physical and mental health (Bright, Knapp, Hinojosa, Alford, & Bonner, Reference Bright, Knapp, Hinojosa, Alford and Bonner2016; Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Bellis, Hardcastle, Sethi, Butchart, Mikton and Dunne2017; Kalmakis & Chandler, Reference Kalmakis and Chandler2015; Merrick et al., Reference Merrick, Ports, Ford, Afifi, Gershoff and Grogan-Kaylor2017). Data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey indicate that 61% of adults report experiencing at least one childhood adversity and 14% report four or more adversities (Merrick, Ford, Ports, & Guinn, Reference Merrick, Ford, Ports and Guinn2018). Especially concerning is the evidence that has shown consistent links between childhood adversities and mental health symptoms of depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Cougle, Timpano, Sachs-Ericsson, Keough, & Riccardi, Reference Cougle, Timpano, Sachs-Ericsson, Keough and Riccardi2010; Edwards, Holden, Felitti, & Anda, Reference Edwards, Holden, Felitti and Anda2003; Goodwin & Stein, Reference Goodwin and Stein2004; Kitzmann, Gaylord, Holt, & Kenny, Reference Kitzmann, Gaylord, Holt and Kenny2003; Sachs-Ericsson, Kendall-Tackett, & Hernandez, Reference Sachs-Ericsson, Kendall-Tackett and Hernandez2007; Wolfe, Crooks, Lee, McIntyre-Smith, & Jaffe, Reference Wolfe, Crooks, Lee, McIntyre-Smith and Jaffe2003). Many studies have taken a cumulative score approach to examining adversities and have found a dose-response effect of the number of adversities on mental health outcomes (Chapman et al., Reference Chapman, Whitfield, Felitti, Dube, Edwards and Anda2004; Merrick et al., Reference Merrick, Ports, Ford, Afifi, Gershoff and Grogan-Kaylor2017). Other studies have examined the individual contributions of different types of adversity and showed that maltreatment adversities were stronger predictors of outcomes than were family dysfunction adversities (Atzl, Narayan, Rivera, & Lieberman, Reference Atzl, Narayan, Rivera and Lieberman2019; Narayan et al., Reference Narayan, Kalstabakken, Labella, Nerenberg, Monn and Masten2017; Ryan, Kilmer, Cauce, Watanabe, & Hoyt, Reference Ryan, Kilmer, Cauce, Watanabe and Hoyt2000). However, in a global study of 21 countries, parental mental illness, child abuse, and neglect were the strongest predictors of psychiatric disorders in adulthood (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, McLaughlin, Green, Gruber, Sampson, Zaslavsky and Angermeyer2010). Some evidence also suggests that maltreatment may be more important for internalizing symptoms and family dysfunction for externalizing problems (Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, Kilmer, Cauce, Watanabe and Hoyt2000).

A potential explanation for discordance in the prior findings may be an individual's perception of the adversity, as similar events may not necessarily be perceived as similarly traumatic by different individuals (Dulmus & Hilarski, Reference Dulmus and Hilarski2003). The developmental timing of the adversity may also lend to different effects, as there are particular sensitive periods for the development of mental health symptoms (Kwong et al., Reference Kwong, Manley, Timpson, Pearson, Heron, Sallis and Leckie2019; Steinberg, Reference Steinberg2013). Multivictimization has also been found to be particularly detrimental (Finkelhor, Ormrod, & Turner, Reference Finkelhor, Ormrod and Turner2007; Turner, Shattuck, Finkelhor, & Hamby, Reference Turner, Shattuck, Finkelhor and Hamby2017), suggesting that those with more adversities are more vulnerable to developing health symptoms. However, there is still uncertainty as to whether particular patterns of co-occurring adversity increase risk for mental health symptoms or the total number of adverse experiences is more critical. The current study sought to clarify the individual contributions of different types of adversity to symptoms of mental health in late adolescence by investigating characteristics such as the perception of the event, age at first occurrence, and the co-occurrence of adversities.

Conceptualization of Childhood Adversity

Recent research on childhood adversities has largely been driven by the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) studies (Felitti et al., Reference Felitti, Anda, Nordenberg, Williamson, Spitz, Edwards and Marks1998; Merrick et al., Reference Merrick, Ford, Ports and Guinn2018). This work conceptualized childhood adversity into domains of household dysfunction (divorce, parental health illness, parental substance use, witnessing intimate partner violence) and maltreatment (sexual abuse, physical abuse, physical neglect, emotional neglect, emotional abuse). However, the ACEs studies were not the first to provide evidence that early trauma affects physical and mental health, as child maltreatment researchers have been documenting these effects for decades (Aber, Allen, Carlson, & Cicchetti, Reference Aber, Allen, Carlson, Cicchetti, Cicchetti and Carlson1989; Erickson, Egeland, & Pianta, Reference Erickson, Egeland, Pianta, Cicchetti and Carlson1989; Kaufman & Cicchetti, Reference Kaufman and Cicchetti1989; Toro, Reference Toro1982). Additionally, some researchers contend that the domains included on the original ACEs questionnaire are incomplete and suggest the addition of other important adverse experiences such as community violence, bullying, discrimination, foster placement, and parental death, among others (Cronholm et al., Reference Cronholm, Forke, Wade, Bair-Merritt, Davis, Harkins-Schwarz and Fein2015; Finkelhor, Shattuck, Turner, & Hamby, Reference Finkelhor, Shattuck, Turner and Hamby2015). The inclusion of these additional adversities and their associations with mental health outcomes suggests that the original conceptualization of ACEs was too constrained and may not be capturing the full spectrum of important adversities. Furthermore, grouping various adversities into domains (i.e., household dysfunction versus maltreatment) creates artificial distinctions that may or may not be relevant to the measurement of adversity or prediction of mental health. Other conceptualizations of adversity such as the dimensional model of adversity and psychopathology are based on the physiological and neurobiological effects of specific experiences (i.e., threat versus deprivation; McLaughlin & Sheridan, Reference McLaughlin and Sheridan2016). Additionally, although exposure in these two domains may co-occur, the downstream consequences of threat versus deprivation are distinct. The dimensional model of adversity and psychopathology also suggests that cumulative risk scores discount the importance of co-occurring adversities and the variability in severity for different adverse experiences. Nonetheless, any dimensional approach has limitations. While no dimensional model can perfectly capture the variety of potential adverse experiences, it is clear that a cumulative score approach limits our understanding of the influence of specific adversities on the development of psychopathology.

Age at Onset

The age at which an adversity occurred is an important factor that affects the degree to which subsequent symptoms manifest. Most of the work in this area has focused on maltreatment, and overall, the findings show that occurrence at an earlier age is more detrimental (Dunn, McLaughlin, Slopen, Rosand, & Smoller, Reference Dunn, McLaughlin, Slopen, Rosand and Smoller2013; Kaplow & Widom, Reference Kaplow and Widom2007; Keiley, Howe, Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, Reference Keiley, Howe, Dodge, Bates and Pettit2001). This is consistent with the theoretical understanding that children need warm, consistent, safe environments to develop secure attachments, which set the stage for critical developmental skills such as emotion regulation (Cicchetti, Reference Cicchetti, Cicchetti and Carlson1989). Supporting this theory, in a longitudinal study from childhood to adulthood, younger age at maltreatment onset (0–5 years) predicted more symptoms of anxiety and depression in adulthood than maltreatment occurring between 6 and 11 years old (Kaplow & Widom, Reference Kaplow and Widom2007). Similarly, in a large sample of children that were assessed from kindergarten through eighth grade, physical abuse that occurred prior to age 5 was associated with more negative effects than if the abuse occurred at later ages (Keiley et al., Reference Keiley, Howe, Dodge, Bates and Pettit2001). On the other hand, several studies have found no age effects. Among youth who were involved with child welfare, there was no effect of the developmental period during which the maltreatment occurred on outcomes (Jaffee & Maikovich-Fong, Reference Jaffee and Maikovich-Fong2011). In addition, in a sample of pregnant women, age at maltreatment was not associated with depressive symptoms (Atzl et al., Reference Atzl, Narayan, Rivera and Lieberman2019). Only one study has examined age of onset for multiple adversities, and the results showed that among psychiatric inpatients, physical and emotional neglect at age 4–5 were associated with increased dissociation, whereas emotional neglect at age 8–9 increased depressive symptoms (Schalinski et al., Reference Schalinski, Teicher, Nischk, Hinderer, Muller and Rockstroh2016). Overall this evidence supports exposure to maltreatment prior to age 5 as particularly critical. However, other types of adversity that may influence the parent–child bond (e.g., parental substance abuse, parental mental illness, divorce) have not been examined, leaving a gap in our understanding regarding the variety of experiences that may affect child mental health outcomes.

Perception of Adverse Experiences

The perception of early adverse experiences also likely contributes to their effects on mental health. That is, whether an individual interprets an event or experience as being upsetting may be more useful to our understanding of the etiology of psychopathology than just asking whether an adversity occurred. While highly stressful or traumatic events have documented effects on the physiological stress system (McEwen, Reference McEwen2000), the correspondence between the perception of stress and the effect on the body is higher when the stressor is perceived as novel, unpredictable, threatening, or involves loss of control (Lupien et al., Reference Lupien, Ouellet-Morin, Hupback, Walker, Tu, Buss, Cicchetti and Cohen2006). For example, in studies of trauma exposure, the perception of fear or helplessness but not the characteristics of the event itself was associated with PTSD symptoms (Boals & Schuettler, Reference Boals and Schuettler2009). The distinction between types of stressors that may be subject to individual differences in perception have been conceptualized by Lupien et al. (Reference Lupien, Maheu, Tu, Fiocco and Schramek2007) as “relative stressors.” In contrast to absolute stressors, which are linked with a universal physiological response due to their life-threatening nature, relative stressors are dependent on the cognitive interpretation of the stressor and do not necessarily elicit a physiological response. Thus, the perception of an event becomes more a more critical influence on responses to these types of stressors. Importantly, the effects of early adversity are also affected by the stress hormones that are linked with the physiological stress response. These hormones have the ability to cross the blood–brain barrier where they affect the brain in ways that impair learning and memory and increase vulnerability to mental health problems (Lupien et al., Reference Lupien, Maheu, Tu, Fiocco and Schramek2007). Thus, the perception of an event as being stressful or upsetting may be integral to understanding the variability in outcomes that is related to adverse experiences. In a study of bereavement among adolescents, the perception of the loss was critical to the influence of the event on depressive symptoms (Harrison & Harrington, Reference Harrison and Harrington2001). Among soldiers, the perception of the combat experience as being traumatic was associated with increased risk for alcohol problems (Vest, Homish, Hoopsick, & Homish, Reference Vest, Homish, Hoopsick and Homish2018). Overall, the evidence demonstrates that not everyone who experiences trauma or adversity develops mental health symptoms (Ozer, Best, Lipsey, & Weiss, Reference Ozer, Best, Lipsey and Weiss2003). Therefore the individual's perception of the event as being upsetting may be important for delineating those who are most vulnerable.

Person-Centered Classification of Co-occurring Adversity

Co-occurrence has often been addressed by using a sum score of the total number of adversities. However, this approach discounts the individual characteristics of each adversity, assumes similar severity across adversities, and has inherent limitations (Barboza, Reference Barboza2018). Another approach has been to include all the individual adversities in one model (i.e., “unpacking”), which can enhance our understanding of the relative strength of associations between adversities and mental health but does not address co-occurrence. Data show that experiencing just one adversity is rare (Finkelhor, Ormrod, Turner, & Hamby, Reference Finkelhor, Ormrod, Turner and Hamby2005; Finkelhor et al., Reference Finkelhor, Ormrod and Turner2007; Shin, McDonald, & Conley, Reference Shin, McDonald and Conley2018), and particularly among maltreated youth co-occurrence is more the rule than the exception (Brown, Rienks, McCrae, & Watamura, Reference Brown, Rienks, McCrae and Watamura2019; Kim, Mennen, & Trickett, Reference Kim, Mennen and Trickett2017). Thus, more attention should be placed on assessing the co-occurrence of adversities.

A number of recent analyses have used latent class analysis (LCA) to categorize individuals based on similar patterns of co-occurring adversities. In a sample of adolescents who were investigated for maltreatment, three classes were found, all indicating multivictimization (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Rienks, McCrae and Watamura2019). In the National Survey of Children's Health, seven classes were indicated, with the majority (76%) being classified into the 0–1-ACE class (Lanier, Maguire-Jack, Lombardi, Frey, & Rose, Reference Lanier, Maguire-Jack, Lombardi, Frey and Rose2018). The other six classes were comprised of different constellations of co-occurring adversities with 2% in the high-ACE class. A sample of first graders who were followed until young adulthood demonstrated a six-class solution, with 57% being classified into the two low-ACE classes (Menard, Bandeen-Roche, & Chilcoat, Reference Menard, Bandeen-Roche and Chilcoat2004). An analysis of juvenile-justice-involved youth showed six classes, again with the majority being assigned to the low-adversity class (40%) and the other five characterized by different combinations of adversity, including a high-adversity class (8%; Logan-Greene, Kim, & Nurius, Reference Logan-Greene, Kim and Nurius2016). This variation in results demonstrates one of the fundamental limitations of LCA, it is specific to the study population and difficult to replicate across samples. The specific characteristics of the samples and differences in the adversities that have been entered into the analyses likely explain the different numbers of classes that have been found across studies. However, despite limited generalizability, these studies demonstrate a variety of patterns of co-occurring adversity and this heterogeneity in experiences would have been missed with a sum score approach.

Although a number of studies have used LCA to examine patterns of co-occurring adversities, only a few have tested the links between class membership and mental health. In a sample of adults from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey, five latent classes were determined to be the best fit for the data and indicated patterns of low/normative adversity (56% of the sample), co-occurring emotional abuse and parental alcohol abuse (30% of the sample), co-occurring emotional abuse, alcohol abuse, and witnessing IPV (6%), sexual abuse (4%), and multiple co-occurring adversities (3%; Barboza, Reference Barboza2018). The high-adversity class reported higher levels of depressive symptoms than all of the other classes did, and the normative class reported the lowest levels. In a sample of undergraduate students who completed the College Student Health Survey, four classes were selected: low ACEs (61%), emotional and physical abuse (13%), nonviolent household dysfunction (17%), and high ACEs (9%; Merians, Baker, Frazier, & Lust, Reference Merians, Baker, Frazier and Lust2019). Again, differences in mental health were primarily between the high- and low-ACEs classes. Among a community of young adults, four classes were indicated, with 46% in the low-ACEs class and 16% in the high- and multiple-ACEs classes (Shin et al., Reference Shin, McDonald and Conley2018). Those in the three multiple-ACEs classes reported more psychological symptoms than did those in the low-ACEs class. An advantage of the LCA approach is the specification of different patterns of co-occurring adversities as well as the adversities that are most highly associated with membership in that class. This can allow for a more nuanced understanding of the relative influence of co-occurrence on the development of mental health symptoms. However, at least one study raises questions about the utility of the LCA approach for assessing associations between co-occurring adversity and mental health. A comparison of LCA versus the cumulative score approach showed that both accounted for a similar amount of variance in outcomes, leaving some uncertainty as to the need for the LCA approach (Merians et al., Reference Merians, Baker, Frazier and Lust2019). Further work is needed to assess the utility of person-centered profiles of adversity for predicting mental health in adolescence.

The Current Study

A number of studies have shown that adversity is linked with increased mental health symptoms by using a cumulative score approach, an individual adversity approach, or a person-centered approach. However, very few have included the perception of the event or the age at occurrence to clarify the importance of specific adversities to the development of mental health symptoms. To address these gaps in the literature, the purpose of the present study was to examine whether the perception, age, or co-occurrence of adverse childhood experiences provided additional information regarding the prediction of mental health symptoms above the simple endorsement (yes/no) of each particular adversity or the cumulative score. To achieve these objectives, we tested: (a) the individual contribution of 11 adverse experiences to mental health symptoms in late adolescence, (b) the perception of how upsetting each adversity was to the participant, (c) the age at first occurrence of each adversity, (d) the total number of items endorsed, and (e) the cumulative upset rating as predictors of mental health symptoms in late adolescence. Our goal was to illuminate the importance of individual adverse experiences to the development of mental health problems and to demonstrate whether the assessment of the perception of the event as upsetting or age of occurrence enhanced the predictive power. Lastly, to assess co-occurrence we used a person-centered approach to delineate heterogeneous classes of youth with similar clusters of adversities and associations with mental health symptoms. This approach enhances an understanding of multiple co-occurring adversities within a sample of high-risk youth. These questions were examined in a sample of child-welfare-involved and community youth. Our assessment of adversity was enhanced by the use of a child welfare sample while allowing more generalizability by the inclusion of community youth who may have experienced adversity but were not referred to child welfare.

Method

Participants

The data were from the fourth assessment (M = 7.2 years after baseline) of an ongoing longitudinal study for examining the effects of maltreatment on adolescent development. The enrolled sample consisted of 454 adolescents aged 9–13 years (241 males and 213 females). Of the original sample, 78% had completed the Time 4 assessment (N = 352). The baseline assessment took place between 2002 and 2005, and the Time 4 assessment took place between 2009 and 2012. At Time 4 the participants were a mean age of 18.24 years (SD = 1.47), approximately evenly split between males and females, and primarily African American (43%) or Latino (34%). The sample demographics can be viewed in Table 1. Attrition analyses (including demographics such as race, gender, age, and maltreatment status) indicated that participants who were not seen at Time 4 were more likely to be male, OR = 1.86, p < .01.

Table 1. Sample characteristics for Time 4

Recruitment

The maltreatment group (n = 303) was recruited from active cases in the Children and Family Services (CFS) agency of a large West Coast city. The inclusion criteria were (a) a new substantiated referral to CFS during the preceding month for any type of maltreatment (e.g., neglect, physical abuse, sexual abuse, or emotional abuse); (b) age of 9–12 years (some turned 13 between scheduling and actual study visit); (c) identified as Latino, African American, or Caucasian (non-Latino); and (d) residing in 1 of 10 Zip codes in a designated county at the time of referral to CFS. With the approval of CFS and the Institutional Review Board of the affiliated university, potential participants were contacted and asked to indicate their willingness to participate.

The comparison group (n = 151) was recruited by using names from school lists of children who were aged 9–12 years and were residing in the same 10 Zip codes as were those in the maltreated sample. The caretakers of potential participants were contacted and asked to indicate their interest in participating. To ensure the fidelity of the comparison sample, the caretakers were asked about their involvement with CFS and none indicated prior or current contact with CFS.

Procedure

The assessments were conducted at an urban research university. After assent and consent were obtained from the adolescent and caretaker, respectively, the adolescent completed questionnaires and tasks during a 4-hr protocol. The measures that were used in the analyses represent a subset of the questionnaires that were administered during the protocol. Both the children and caretakers were paid for their participation according to the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health standard compensation for healthy volunteers.

Measures

Self-reported childhood adversities

The Comprehensive Trauma Interview (CTI; Noll, Horowitz, Bonnano, Trickett, & Putnam, Reference Noll, Horowitz, Bonnano, Trickett and Putnam2003) was used at Time 4 to assess self-reported lifetime adversities as conceptualized in the expanded ACEs questionnaires and polyvictimization literature by Finkelhor (Finkelhor et al., Reference Finkelhor, Shattuck, Turner and Hamby2015) and others (Cronholm et al., Reference Cronholm, Forke, Wade, Bair-Merritt, Davis, Harkins-Schwarz and Fein2015). The CTI assesses 19 different adverse experiences including parental divorce, parental incarceration, witnessing IPV, household substance use, death of parent, foster care placement or other parental separation, sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional abuse, emotional neglect, and physical neglect. Other items such as self-harm, being left alone to care for children, and being left with someone who scared you were not included because they did not map onto the original or expanded ACEs constructs. The CTI was administered via interview by a trained research assistant. Other studies have shown test-retest reliability ranging from .45 to .76 depending on the maltreatment type (Barnes, Noll, Putnam, & Trickett, Reference Barnes, Noll, Putnam and Trickett2009; Fergusson, Horwood, & Woodward, Reference Fergusson, Horwood and Woodward2000). Each stem question was answered yes/no, and if an item was answered affirmatively further follow-up questions were asked including age at event(s), upset rating, and a description of what happened. To ascertain divorce and parental incarceration, answers to the question “Has anyone ever moved away from you” were reviewed and manually coded. Witnessing IPV was obtained from the question “Have there been times when you have seen or heard adults that take care of you say mean, insulting, or threatening things to each other; hit each other; or hurt each other physically?” Household member substance use was obtained from the question “Have the people who take/took care of you had problems with drugs or alcohol?” Death of a parent was manually coded based on the text answer to “Was there ever a time when someone close to you was very sick or died?” (coded only if the response indicated a parent's death). Foster care or separation from parent was manually coded from the question “Have you ever had to go live with someone else because of what was happening in your family?” (coded if they indicated that they were separated from a parent either by choice or not). Childhood sexual abuse was obtained from one item that asked, “Has anyone ever done something, or tried to do something sexual to you that you didn't want?” Physical abuse was also one item that asked, “Have you ever been hit or beaten or physically mistreated by any adults?” Physical neglect was coded as the presence of any one of four items: (1) “Have there been times when you did not have enough to eat, did not have clothes, medicine, or medical attention, or didn't have a place to sleep?”; (2) “Have there been times when the person(s) who was supposed to be taking care of you couldn't do it very well because of the problems they were having?”; (3) “Have there been times when the place you were living has been without running water or electricity or other things that made it hard to live there?”; and (4) “Were there times when you didn't have a place to live and had to stay in a car or in a shelter?” Emotional neglect was one item that asked, “Have there been times when you felt rejected by your family?” Finally, emotional abuse was one item that asked, “Have there been times in your life when the adults that take care of you said mean or insulting things to you, put you down, or told you that you were no good?”

Dichotomous scoring

Each item was endorsed as yes/no. These were summed to create a total score for the number of ACEs that each participant had experienced.

Upset rating

For any item that the participant endorsed, a number of follow-up questions were asked. This included a rating of “How upsetting was this for you?” on a scale of 1 (not at all upsetting) to 5 (extremely upsetting). The upset rating was created in two ways: (a) including all of the participants and coding the upset rating as zero for those who did not endorse a particular item and (b) only including the upset rating for those who endorsed the item. For the present analyses we used the item-level upset rating as well as a cumulative score of the upset rating of all 11 items. The upset rating cumulative score ranged from 0 to 40 in the current sample (those who did not endorse the event were coded zero).

Age at first occurrence

One of the follow-up questions on the CTI asked how old the participant was when the event occurred. For maltreatment experiences that are less discrete and may occur over time, such as physical or emotional neglect, we used the age at the first occurrence.

Depressive symptoms

Adolescents completed the 27-item Children's Depression Inventory. (Kovacs, Reference Kovacs1981, Reference Kovacs1992) They rated statements such as “I am sad all the time” and “I feel like crying every day,” on a 3-point scale (range of possible scores = 0 to 54). Cronbach alpha for T4 was .89. It has been shown to have good internal consistency ranging from .80 to .94, and test–retest reliability scores have been shown to range from .76 to .82 (Saylor, Finch, Spirito, & Bennett, Reference Saylor, Finch, Spirito and Bennett1984; Smucker, Craighead, Craighead, & Green, Reference Smucker, Craighead, Craighead and Green1986).

Posttraumatic stress disorder

Symptoms of PTSD occurring in the past couple of months were assessed by using the Youth Symptom Survey Checklist (Margolin, Reference Margolin2000). This is a 17-item self-report measure of symptoms from the diagnostic criteria for PTSD that are listed in the DSM IV-TR such as hyperarousal, avoidance/numbness, and re-experiencing. Whereas most PTSD measures ask about symptoms that are related to a specific event, this questionnaire is not anchored to any specific traumatic event. Answer options range from 1 = not at all to 4 = almost always. The total score was used for this analysis (17 items; α = .88) and can range from 17 to 68.

Anxiety

The 39-item Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (March, Parker, Sullivan, Stallings, & Conners, Reference March, Parker, Sullivan, Stallings and Conners1997) was used to measure anxiety symptoms. It has been found to have good internal consistency (range for the subscales is .70 to .89), good test-retest reliability, invariant factor structure across gender and age, and discriminant validity (March et al., Reference March, Parker, Sullivan, Stallings and Conners1997). The nine items on the separation anxiety subscale (e.g., “I get scared when my parents go away”) were removed from the scale at T4 due to developmental inappropriateness. Items such as “I feel tense or uptight” were rated from 0 to 3 (never true about me to often true about me) yielding a possible total score that ranged from 0 to 30. Internal consistency reliability was .89 at T4.

Externalizing problems

The Youth Self Report was used to measure externalizing behavior (Achenbach & Rescorla, Reference Achenbach and Rescorla2001). This widely used child report measure is a companion to the parent report and has substantial evidence of reliability and validity in various populations (Achenbach & Rescorla, Reference Achenbach and Rescorla2001). The externalizing subscale is composed of aggression (17 items) and rule-breaking/delinquency (12 items). Each item is rated from 0 to 2 (not at all to a lot) with a possible range of 0 to 58. Cronbach alpha for this measure was .89 at T4.

Data Analysis

First, in Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén2006) we used a path model to examine the individual main effects of all 11 ACEs items (i.e., divorce, parental incarceration, witnessing IPV, household member substance use, death of a parent, foster care or separation from parent, sexual abuse, physical abuse, physical neglect, emotional neglect, and emotional abuse) on the four mental health outcomes (depressive symptoms, PTSD symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and externalizing behavior). All of the exposure variables were allowed to correlate and all of the outcome variables were allowed to correlate. The model was fully saturated and controlled for maltreatment group status, gender, race (minority vs. White), and T4 age on the outcomes. Path modeling allows the inclusion of all of the variables in the same model, reducing the need for multiple tests and the reduction of familywise error. It also allows covariance within predictors and outcomes, which results in a more accurate representation of the individual parameter estimates.

Next, using the same path modeling framework, we examined the upset rating of each item as a predictor of the four mental health outcomes. We then tested a third model, with the age at the first occurrence of each item as predictors of mental health. Finally, in two separate models we examined the main effects of the cumulative upset rating (sum of all of the upset ratings) versus the sum of the 11 dichotomous items (coded yes/no) on mental health. In all of the models we controlled for maltreatment group status, gender, race, and T4 age on the outcomes.

Finally, we used LCA in Mplus to examine heterogeneous subgroups of participants with similar patterns of adverse experiences. We fit models from 1- to k-class solutions, adding classes until the fit statistics did not improve. We then compared the fit statistics of the various class solutions to determine the best-fitting model that suited our substantive interpretation. Smaller values of the -2 log likelihood, Akaike Information Criteria, Bayesian Information Criteria, and the sample-size-adjusted Bayesian Information Criteria all indicate better model fit. In addition, we tested the significance of a k-1 model fit by using the Vuong–Lo–Mendell–Rubin likelihood ratio test (VLMR), Lo–Mendell–Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test (LMR), and the bootstrapped likelihood ratio test (BLRT). A nonsignificant value for any of these indices indicates that the fewer-class solution is a better fit to the data. In addition, we used the criteria of class homogeneity and separation, which allows for a meaningful interpretation of the classes. Specifically, we used only items with high (>.70) or low (<.30) probability of endorsement to describe class characteristics. Additionally, class separation was assessed by items with high (>5.0) or low (<0.20) odds of endorsing a particular item. All of the model fit criteria were assessed in conjunction to determine the final class solution. We then used the 3-step BCH procedure to test for differences between the classes for demographic characteristics and mean levels of ACEs. This method was also used to test the mean differences in the four mental health outcomes by class membership, including the same set of covariates as in the other models. This approach involved estimating the LCA model, assigning participants to classes, and estimating the differences between the classes on the specified auxiliary variables (Vermunt, Reference Vermunt2010). Most importantly, this technique accounts for uncertainty in class assignment when calculating the mean differences between the classes.

Due to skewness of some of the adversity variables, univariate and multivariate nonnormality was addressed by using the maximum likelihood robust estimator in Mplus. Full-information maximum likelihood estimation (Arbuckle, Reference Arbuckle, Marcoulides and Schumacker1996) in Mplus was used to address missing data and incorporate the incompleteness of data in parameter estimates. The use of full-information maximum likelihood estimation results in unbiased parameter estimates when data are missing at random or missing completely at random. Even when the assumptions regarding missing data are not fully met, full-information maximum likelihood produces more valid estimates than does listwise deletion (Little, Reference Little2002).

Results

Descriptives

Table 2 shows the frequency with which each item was endorsed. Among the total sample, the most prevalent adversity was emotional neglect (40%), followed closely by physical neglect (39%) and witnessing IPV (38%). Within the maltreated group, the highest prevalence was for physical neglect (53%), followed by emotional neglect (45%) and witnessing IPV (43%). For the comparison group, the items with the most endorsement were witnessing IPV (30%) and emotional neglect (30%). Including only those cases with an upset rating of 3 or higher (moderately upsetting to extremely upsetting) did not reduce the number of endorsements by more than 5%. The most reduction was seen for physical neglect, which decreased from 39% to 32%, when taking into account only those who reported that the experience was moderately upsetting to extremely upsetting.

Table 2. Frequency of childhood adversity items

Note: Frequency (n) and percentage are shown for individual items, and mean and standard deviation (SD) are shown for the total scores. aindicates significant group differences for age at 1st occurrence at p < 05. Upset rating: 1–2 = not at all, a little upsetting; 3–5 = moderately, very, extremely upsetting. The upset rating for only those endorsing the item excluded those with no score. The upset rating with all participants recoded those with no score into zero. Analysis of covariance was used to compare mean upset rating and age at 1st incident between maltreated and comparison groups, controlling for age, race, and gender.

The mean age between the groups was tested for the age of the first occurrence of each item. The result of the analysis of covariance showed that self-reported separation from parents occurred at a significantly younger age for the maltreated (M = 8.90, SD = 3.78) versus the comparison youth (M = 14.00, SD = 3.11), F (1, 48) = 13.36, p < .01. In addition, the age at first occurrence of sexual abuse, F (1, 66) = 5.10, p < .05, and emotional neglect, F (1, 138) = 8.86, p < .01, was significantly lower for the maltreated group (see Table 2 for means).

Individual Adversity Experiences

Dichotomous coding

As shown in Table 3, there were a number of significant main effects for each item (scored yes/no) on the four mental health outcomes after controlling for the effects of the other adversities. However, it should be noted there were more nonsignificant parameters than significant ones. Specifically, parental incarceration was associated with anxiety symptoms, β = 0.08, p < .05; sexual abuse was associated with depressive symptoms, β = 0.15, p < .05; emotional neglect was associated with depressive symptoms, β = 0.34, p < .01, PTSD symptoms, β = 0.23, p < .01, and anxiety symptoms, β = 0.14, p < .05; and emotional abuse was associated with externalizing behavior, β = 0.16, p < .05. For all of the main effects, the direction of the coefficients indicated that endorsing the item was associated with higher levels of mental health symptoms. The R 2 for depressive symptoms = .14, for PTSD symptoms = .14, for anxiety symptoms = .10, and for externalizing behavior = .09.

Table 3. Standardized regression coefficients from path models for testing the main effects of ACES variables (dichotomous coding, upset rating, age) on mental health

Upset rating

As mentioned, we used the upset rating coded as zero for those who did not endorse the item. There was a significant effect of the upset rating for parental incarceration, on anxiety symptoms, β = 0.08, p < .05. For maltreatment items there was a significant effect of the upset rating for sexual abuse on depressive symptoms, β = 0.15, p < .05, and externalizing behavior, β = 0.12, p < .05. There was also a significant effect of the upset rating for emotional neglect on depressive symptoms, β = 0.34, p < .01, PTSD symptoms, β = 0.23, p < .01, anxiety symptoms, β = 0.14, p < .05, and externalizing behavior, β = 0.15, p < .05. Overall, the pattern of significant main effects was very similar for the dichotomous versus the upset rating. The R 2 for depressive symptoms = .23, for PTSD symptoms = .18, for anxiety symptoms = .13, and for externalizing behavior = .11.

We also tested the upset rating only for those participants who endorsed the item (removing those who did not endorse). We had to remove four items: divorce, parental death, parental incarceration, and separation from parent due to low covariance coverage. The results showed that none of the adversity items was significantly associated with the outcomes.

Age at first occurrence

Due to low frequency of age for some adversities, we could not examine all of the age variables. Specifically, divorce, parental death, and parental incarceration, and separation from parent were dropped for the model due to low covariance coverage. Therefore, we examined one model with the remaining seven items. The results showed that a younger age at household member substance use was associated with higher anxiety symptoms, β = -0.35, p < .05. Younger age at first emotional neglect was associated with higher PTSD symptoms, β = -0.30, p < .01. Older age at first occurrence of physical neglect was associated with higher PTSD symptoms, β = 0.27, p < .05, and externalizing behavior, β = 0.24, p < .01. Finally, older age at first emotional abuse occurrence predicted PTSD symptoms, β = 0.32, p < .01. The R 2 for depressive symptoms = .07, for PTSD symptoms = .09, for anxiety symptoms = .17, and for externalizing behavior = .12.

Cumulative Upset Rating Versus Sum Score of Items

The results from the two models with (a) a cumulative upset rating and (b) a sum score of the dichotomous items were nearly identical. This is not surprising given that the correlation between the ACEs total score and the cumulative upset rating was r = .96, p < .01. The cumulative upset rating was associated with depressive symptoms, β = 0.30, p < .01; R 2 = .11, PTSD symptoms, β = 0.38, p < .01; R 2 = .14, anxiety symptoms, β = 0.21, p < .01; R 2 = .10, and externalizing behavior, β = 0.23, p < .01; R 2 = .06. All of the coefficients indicated that the higher the cumulative score the more symptoms. The sum score showed the same pattern of results, with main effects on depressive symptoms, β = 0.32, p < .01; R 2 = .13, PTSD symptoms, β = 0.39, p < .01, R 2 = .14, anxiety symptoms, β = 0.23, p < .01, R 2 = .11, and externalizing behavior, β = 0.28, p < .01; R 2 = .09.

Latent Class Analysis

The model fit indices are shown Table 4. Although the Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin test and the Lo–Mendell-Rubin tests indicated that the 2-class solution was the best fit, the Bootstrapped log-likelihood ratio test indicated that the 3-class solution was a better fit. In addition, the information criteria such as the -2 log likelihood, Akaike information criterion, and the sample size adjusted Bayesian information criterion all indicated that the 3-class solution was preferable. We graphed the conditional probability of endorsing each item in Figure 1. Using the class homogeneity criteria specified previously, Class 1 was labeled “high family violence, substance use, and physical neglect,” Class 2 was labeled “high emotional abuse and emotional neglect,” and Class 3 was named “low adversity.” The class separation between Classes 1 and 2 was primarily on household substance use, between Classes 1 and 3 on emotional neglect, and between Classes 2 and 3 on witnessing IPV and emotional neglect. The associations with demographic variables (Table 5) showed that those in the maltreated group were more likely than the comparison youth to be in Class 1 (high family violence, substance use, and physical neglect) than in Class 2 (high emotional abuse and emotional neglect) or Class 3 (low adversity). However, maltreated youth were not more likely than were those in the comparison group to be in Class 2 than in Class 3, demonstrating that a substantial proportion of our comparison youth had been experiencing multiple adversities (mainly in the form of witnessing IPV, emotional abuse, and emotional neglect) and that over half of the maltreated group had reported few adversities. The total sum score of the adversity items was significantly different between each of the three classes, χ2 = 975.89, p < .01, with Class 1 reporting the most adversities (M = 6.11, SE = 0.14; Class 1 versus Class 2: χ2 = 70.20, p < .01; Class 1 versus 3: χ2 = 687.71, p < .01), followed by Class 2 (M = 4.12, SE = 0.12; Class 2 versus Class 3: χ2 = 379.72, p < .01), and Class 3 (M = 1.04, SE = 0.08).

Figure 1. Item-level probabilities for the adversity variables. The results indicted a 3-class solution: Class 1: high family violence, substance use, and physical neglect; Class 2: high emotional abuse & emotional neglect; and Class 3: low adversity.

Table 4. Model fit indices for latent class analysis

Note: -2LL = negative 2 × log likelihood; AIC = Akaike Information Criteria; BIC = Bayesian Information Criteria; aBIC = sample size adjusted Bayesian Information Criteria; VLMR=Vuong–Lo–Mendell–Rubin test; LMR = Lo–Mendell–Rubin test; BLRT = Bootstrapped log-likelihood ratio test.

Table 5. Class membership and demographic variables

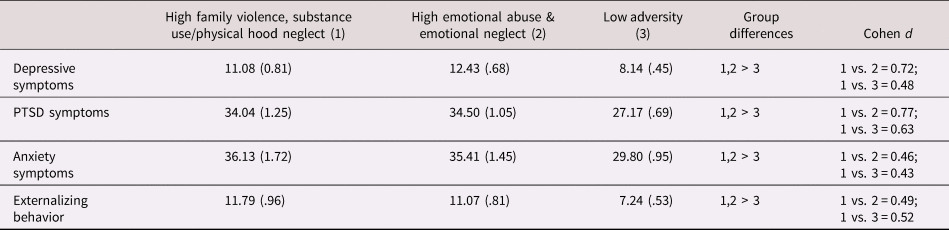

The results of the mean differences tests showed significant effects of class membership on all four of the mental health outcomes (overall Chi-square: depressive symptoms: χ2 = 32.70, p < .01; PTSD symptoms: χ2 = 41.82, p < .01; anxiety symptoms: χ2 = 16.22, p < .01; externalizing: χ2 = 20.48, p < .01). As seen in Table 6, individuals in Class 1 and 2 (high-adversity classes) reported significantly more depressive symptoms than did those in Class 3 (low adversity) (1 vs. 3: χ2 = 7.76, p < .01; 2 vs. 3: χ2 = 27.07, p < .01). Similar differences were found for PTSD symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and externalizing behavior, with individuals in Classes 1 and 2 reporting more problems than did those Class 3 (PTSD symptoms 1 vs. 3: χ2 = 14.01, p < .01; 2 vs. 3: χ2 = 32.21, p < .01; externalizing 1 vs. 3: χ2 = 10.34, p < .01; 2 vs. 3: χ2 = 12.48, p < .01; anxiety symptoms 1 vs. 3: χ2 = 7.25, p < .01; 2 vs. 3: χ2 = 11.70, p < .01). The two high-adversity classes (Class 1 and 2) were not different from each other on any of the outcomes. The mean scores on each outcome by class membership and Cohen d effect sizes for the pairwise comparisons can be found in Table 6. The R 2 for depressive symptoms = .13, for PTSD symptoms = .13, for anxiety symptoms = .11, and for externalizing behavior = .09.

Table 6. Mean levels of mental health symptoms for each latent class

Note: The values are expressed as M (SD) for the three classes, and mean differences were tested by using the 3-step BCH method in Mplus.

Discussion

The current study extended our knowledge regarding the individual contribution of different adverse experiences to mental health symptoms in late adolescence by including the perception of how upsetting each experience was to the adolescent and the age at the first occurrence. We also sought to move beyond simple sum scores of adverse experiences by using a person-centered approach to classifying individuals with similar co-occurrence of adversities. Overall, the results showed that the use of an upset rating may enhance the prediction of some mental health outcomes and that the age of occurrence seems to be most critical for physical neglect and emotional abuse. Our findings also indicate that although the adversity sum score was a potent predictor of all mental health outcomes, the sum score obscures information about the importance of individual adversities. Finally, the LCA provided unique information about the patterns of co-occurring adversity in this sample and that membership in either of the multiple-adversity classes was associated with higher levels of mental health symptoms.

Dichotomous Coding Versus Upset Rating

When we used the upset ratings (including those who did not endorse) in the model, the results were fairly similar to the model with the dichotomous items, with a few exceptions. Our results using the dichotomous items showed that emotional neglect had a strong effect on depressive, PTSD, and anxiety symptoms and emotional abuse had a strong association with externalizing behavior. These effects were mostly the same for the upset rating model. The inclusion of the upset rating in the model also indicated a significant effect of emotional neglect on externalizing behavior. This main effect was not present in the dichotomous model, though the parameter estimates were quite similar in the two models (and reached statistical significance only in the upset rating model). The main effects of emotional abuse and emotional neglect on mental health are consistent with the results from a nationally representative study in the US, which showed that all forms of emotional maltreatment were associated with mood, anxiety, and PTSD diagnoses (Taillieu, Brownridge, Sareen, & Afifi, Reference Taillieu, Brownridge, Sareen and Afifi2016). Another notable difference between the dichotomous and upset rating models was that the dichotomous sexual abuse variable was only associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms, whereas the upset rating was associated with both depressive symptoms and externalizing behavior. Although a range of mental health symptoms have been linked with childhood sexual abuse, a systematic review indicates that among adults depressive symptoms is the most well-supported psychological outcome (Putnam, Reference Putnam2003). In the present study, other types of maltreatment (physical abuse and physical neglect) were not associated with any of the outcomes after controlling for the effects of the other adversities. This is surprising given evidence from numerous studies that these types of maltreatment have effects on at least one of these mental health outcomes (Norman et al., Reference Norman, Byambaa, De, Butchart, Scott and Vos2012). Perhaps the difference emerged because we controlled for the other adversities and maltreatment types in the model; it may be that physical abuse and physical neglect co-occur with multiple other adversities and do not explain additional variance. Other studies that have “unpacked” the individual effects of ACEs items have found an absence of effects of physical neglect on depression after controlling for the other adversities (Merrick et al., Reference Merrick, Ports, Ford, Afifi, Gershoff and Grogan-Kaylor2017) as well as an absence of an effect of physical abuse on both internalizing and externalizing problems (Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, Kilmer, Cauce, Watanabe and Hoyt2000). Lastly, household member substance use was associated with lower depressive symptoms only for the dichotomous coding. This may be because adolescents with depression often self-medicate with substances (Bolton, Robinson, & Sareen, Reference Bolton, Robinson and Sareen2009; Wilkinson, Halpern, & Herring, Reference Wilkinson, Halpern and Herring2016), which may be more available and permissible in a household with substance-using members (Chuang, Ennett, Bauman, & Foshee, Reference Chuang, Ennett, Bauman and Foshee2009; McLaughlin, Campbell, & McColgan, Reference McLaughlin, Campbell and McColgan2016). The high correlation between the dichotomous coding and upset rating variables indicates that we were not capturing much more unique variance with the use of the upset rating, and it may also reflect the highly traumatic types of experiences that were being queried on the CTI. When we used the upset rating of only those participants who endorsed each particular item, there were no significant effects on any of the outcomes. These results indicate that adding an upset rating may not contribute much added information above a dichotomous coding, as most of the events were rating as severely upsetting. These findings have implications for ACEs screening in clinical settings where the dichotomous scoring is the standard. However, the results also suggest that summing the items may not be the best indication of which treatment may be most effective, given that there were different associations with the mental health outcomes based on the type of adversity.

Age at First Occurrence

The age at first occurrence did lead to some additional nuances to our prediction of mental health symptoms. Younger age at first occurrence of emotional neglect predicted PTSD symptoms and younger age of household member substance use predicted anxiety symptoms. These findings echo those showing that earlier age at maltreatment is more detrimental (Kaplow & Widom, Reference Kaplow and Widom2007; Keiley et al., Reference Keiley, Howe, Dodge, Bates and Pettit2001). However, older age at first occurrence of physical neglect was associated with PTSD symptoms and externalizing symptoms. Older age at first occurrence of emotional abuse also predicted PTSD symptoms. Interestingly, PTSD symptoms is an outcome that is not typically associated with nontrauma experience such as neglect, although our LCA showed that physical neglect was clustered with other adversities that are more strongly linked with PTSD symptoms (witnessing IPV, physical abuse). The mixed findings regarding age are somewhat surprising, but few prior studies have examined age by the individual types of adversity. The finding of younger age of emotional neglect on PTSD symptoms as opposed to older age for physical neglect and emotional abuse suggests that, consistent with attachment theory, a warm, caring, stable caring environment is necessary early in development to develop resilience against trauma (Cicchetti & Toth, Reference Cicchetti and Toth1995).

Person-Centered Adversity Profiles

The results of the LCA indicated three classes: (1) high family violence, substance use, and physical neglect, (2) high emotional abuse and emotional neglect, and (3) low adversity. Interestingly, other studies that have used a person-centered approach to understanding the clustering of adversities have also found that parental substance use clustered with emotional abuse, as was found in in our study (Barboza, Reference Barboza2018; Rebbe, Nurius, Ahrens, & Courtney, Reference Rebbe, Nurius, Ahrens and Courtney2017). However, most other studies have found a higher number of class solutions than we did in our sample (Barboza, Reference Barboza2018; Lanier et al., Reference Lanier, Maguire-Jack, Lombardi, Frey and Rose2018; Logan-Greene et al., Reference Logan-Greene, Kim and Nurius2016; Merians et al., Reference Merians, Baker, Frazier and Lust2019; Shin et al., Reference Shin, McDonald and Conley2018). Despite the variation in number of classes, a similar feature across these studies is that the class with highest adversity was always characterized by the presence of emotional abuse, as we also observed (Lanier et al., Reference Lanier, Maguire-Jack, Lombardi, Frey and Rose2018; Merians et al., Reference Merians, Baker, Frazier and Lust2019; Rebbe et al., Reference Rebbe, Nurius, Ahrens and Courtney2017). The use of LCA illuminates more nuances of the multiple co-occurring adversities that these youth had experienced. For example, the high-adversity class was characterized primarily by household substance use, witnessing IPV, physical neglect, and emotional abuse. This seems to describe a home life where there may be caretakers with substance abuse who engage in IPV, emotionally berate their child, or fail to provide for their basic needs. This paints the picture of a dysfunctional household where the child is not necessarily being harmed physically but is still being exposed to a psychologically toxic environment.

Not surprisingly, more maltreated than comparison youth were assigned to the high-adversity class, which was characterized by witnessing IPV, household substance use, physical neglect, emotional neglect, and emotional abuse. However, an almost equal number of maltreated and comparison youth were assigned to the middle-adversity class (characterized by emotional neglect and emotional abuse) and the low-adversity class. These findings indicate that while the majority of maltreated youth experienced multiple adversities and victimization experiences, a substantial number also reported few adversities. This is commensurate with a study of youth aging out of foster care, where the authors found that over half of the participants had experienced a low number of adversities (Rebbe et al., Reference Rebbe, Nurius, Ahrens and Courtney2017). On the other hand, this finding contradicts that of another study of children who were investigated for maltreatment, where no low-adversity class was indicated (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Rienks, McCrae and Watamura2019). The possibility of a class of youth with low adversity suggests that not all youth who have contact with child welfare necessarily experience high adversity and poor mental health outcomes. This may be due to a subset of resilient youth in the child welfare group, which has significant implications for intervention.

There were significant differences between the low-adversity class and the two high-adversity classes for all four mental health outcomes. Notably, while the use of LCA did lead to important distinctions in the clustering of adverse experiences, it did not distinguish between the outcomes of youth with high co-occurrence of adversity. Classes 1 and 2 did have many overlapping adversities and were not as well separated as Class 3 was, which may have resulted in the similarity in outcomes. In other studies that have used person-centered approaches, the low-adversity class was always less symptomatic than the other classes were and different combinations of adversities did indicate differences in mental health (Barboza, Reference Barboza2018; Merians et al., Reference Merians, Baker, Frazier and Lust2019; Shin et al., Reference Shin, McDonald and Conley2018).

Limitations

There are some limitations to this study that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, due to the way the CTI was constructed, the upset rating had very little variability, resulting in a high correlation between the cumulative upset rating score and the sum score of the dichotomous items. Therefore, very little unique information was obtained from the cumulative upset ratings. This is likely because the items on the CTI were designed to ask about traumatic/upsetting events, so most participants scored them as highly upsetting. We also had very low frequency for some of the adversity items, which limits their variance and decreases power to detect significant effects. It should also be noted that previous studies have shown low test-retest reliability for some types of maltreatment for the CTI, which may account for the absence of main effects for some of the adversities. Second, LCA is a sample-specific technique and cannot be generalized to other populations. It is, however, a more appropriate tool for accounting for co-occurring adversities than sum scores are. We decided to combine the maltreated and comparison groups to address self-reported adversities for both groups. While we controlled for maltreatment group status in our models, the higher prevalence of adversities in the maltreatment group may be driving the effects with the outcomes. Third, we were not able to include other adversities that have been found to be important for predicting functioning such as bullying, exposure to community violence, or discrimination. The lack of significant associations with age for some of the adversities may be due to the chronicity of the experience, making the age at first occurrence less relevant. We also had to drop four of the items because there was low variance for the age and upset rating variable. This leaves us without information regarding those types of adversities. Although the retrospective self-report of adversities has been widely used, there is inherent bias in self-report, which contributes to the possible underestimation (due to stress-induced blocking out of events) or overestimation (due to perception of minor events as stressful) of the prevalence of adversities in this sample. Lastly, the perception of how upsetting past events were may be confounded with current distress, leading to the significant associations with current mental health.

Conclusions

The use of sum scores for childhood adversities has been used as a method for simplifying co-occurrence (Dong et al., Reference Dong, Anda, Felitti, Dube, Williamson, Thompson and Giles2004; Dube et al., Reference Dube, Felitti, Dong, Chapman, Giles and Anda2003; Dube et al., Reference Dube, Miller, Brown, Giles, Felitti, Dong and Anda2006). However, the findings from this study and others (Atzl et al., Reference Atzl, Narayan, Rivera and Lieberman2019; Narayan et al., Reference Narayan, Kalstabakken, Labella, Nerenberg, Monn and Masten2017; Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, Kilmer, Cauce, Watanabe and Hoyt2000) demonstrate that some adverse experiences, maltreatment experiences in particular, may be more critical to the development of mental health problems. By using a sum score where all types of adversity are weighted similarly, the relative importance of different types of adverse experiences is negated. In addition, the implications for treatment for these youth are difficult to address when there is no indication of which adversities they had experienced. Commensurate with other studies, our work suggests that maltreatment experiences are more influential than are other types of adversities when assessing mental health in adolescence. Our findings also indicate that addressing the nuances of these experiences such as the perception or the age of occurrence may enhance the detection of mental health problems. Lastly, our results support the groundswell of studies that have used a person-centered approach to capture the nuances of co-occurring adversities. It is clear from this and other studies that have used person-centered approaches that co-occurrence is common and latent class approaches may yield more useful information regarding the patterns of co-occurring adversities than sum score approaches do. However, the utility in these classes for predicting outcomes is still equivocal. Further work is necessary to determine whether tailored approaches to addressing childhood adversities should be implemented in order to effectively reduce their effects on mental health in adolescence.

Financial Support

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health Grants R01HD39129, R01DA024569 (to P. K. Trickett, Principal Investigator).