Exposure to early adversity such as maltreatment or poverty increases risk for the development of childhood externalizing behaviors such as rule breaking and noncompliance (Chang, Schwartz, Dodge, & McBride-Change, Reference Chang, Schwartz, Dodge and McBride-Chang2003; Cullerton-Sen et al., Reference Cullerton-Sen, Cassidy, Murray-Close, Cicchetti, Crick and Rogosch2008; Deater-Deckard, Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, Reference Deater-Deckard, Dodge, Bates and Pettit1998; Hicks, South, DiRago, Iacono, & McGue, Reference Hicks, South, DiRago, Iacono and McGue2009; Katz & Gottman, Reference Katz and Gottman1993; Keiley, Howe, Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, Reference Keiley, Howe, Dodge, Bates and Pettit2001; McLeod & Nonnemaker, Reference McLeod and Nonnemaker2000; Slopen, Fitzmaurice, Williams, & Gilman, Reference Slopen, Fitzmaurice, Williams and Gilman2010). However, not all children who experience early adversity develop externalizing behaviors (Criss, Pettit, Bates, Dodge, & Lapp, Reference Criss, Pettit, Bates, Dodge and Lapp2002; Fergusson & Horwood, Reference Fergusson, Horwood and Luthar2003). Biobehavioral theories propose that physiological reactivity and regulation interact with early experiences to increase risk for the development of externalizing problems (e.g., Scarpa & Raine, Reference Scarpa and Raine2004). In the current study, we investigated this idea using two samples of school-aged children who varied in exposure to early adversity: (a) a group of children who had been referred to Child Protective Services (CPS) in infancy due to risk for maltreatment and (b) a group of children without CPS involvement, matched to the CPS-referred sample on age and gender. Specifically, we tested the hypothesis that the association between early CPS involvement (i.e., risk for maltreatment) and externalizing problems in middle childhood depends on children's parasympathetic nervous system regulation, as measured by respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA).

Adversity and the Development of Externalizing Behaviors

Externalizing problems are behaviors that are impulsive, disruptive, aggressive, or antisocial (see Achenbach & Edelbrock, Reference Achenbach and Edelbrock1978, for a review). Typically, externalizing problems are most common during toddlerhood and then decrease over the course of development (e.g., Fanti & Heinrich, Reference Fanti and Henrich2010; Mesman et al., Reference Mesman, Stoel, Bakermans-Kranenburg, van IJzendoorn, Juffer, Koot and Alink2009). However, for some youth, externalizing behaviors persist throughout development and lead to problematic outcomes, such as peer rejection, poor academic achievement, and more severe psychopathology (e.g., Scarpa & Raine, Reference Scarpa and Raine2004). A robust literature indicates that exposure to early adversity is a primary risk factor for the development of externalizing problems (Chang et al., Reference Chang, Schwartz, Dodge and McBride-Chang2003; Cullerton-Sen et al., Reference Cullerton-Sen, Cassidy, Murray-Close, Cicchetti, Crick and Rogosch2008; Deater-Deckard et al., Reference Deater-Deckard, Dodge, Bates and Pettit1998; Hicks et al., Reference Hicks, South, DiRago, Iacono and McGue2009; Katz & Gottman, Reference Katz and Gottman1993; Keiley et al., Reference Keiley, Howe, Dodge, Bates and Pettit2001; McLeod & Nonnemaker, Reference McLeod and Nonnemaker2000; McLoyd, Reference McLoyd1998; Slopen et al., Reference Slopen, Fitzmaurice, Williams and Gilman2010). Experiencing maltreatment, defined as parental behaviors that are abusive or neglectful, is a particularly potent risk factor for externalizing problems (Cicchetti & Carlson, Reference Cicchetti and Carlson1989) and is qualitatively distinct from other forms of early adversity such as poverty. Maltreatment in early childhood is associated with elevated rates of aggressive behavior and externalizing disorders in later childhood (Bolger & Patterson, Reference Bolger and Patterson2001; Shields & Cicchetti, Reference Shields and Cicchetti1998; Van Zomeren-Dohm, Xu, Thibodeau, & Cicchetti, Reference Van Zomeren-Dohm, Xu, Thibodeau and Cicchetti2015) and adulthood (Bland, Lambie, & Best, Reference Bland, Lambie and Best2018).

Interactional Model of Risk for Externalizing Behavior

Externalizing disorders are characterized by emotional and behavioral impulsivity in the absence of effective regulation (Beauchaine, Gatze-Kopp, & Meade, Reference Beauchaine, Gatzke-Kopp and Mead2007). For this reason, maltreated children who exhibit difficulties regulating their emotions may be particularly vulnerable to later externalizing problems (Halligan et al., Reference Halligan, Cooper, Fearon, Wheeler, Crosby and Murray2013; Shields & Cicchetti, Reference Shields and Cicchetti1998). In contrast, maltreated children who are more effective at regulating their emotions may be protected from such outcomes. RSA, a measure of parasympathetic nervous system activity, has been proposed as a physiological indicator of emotion regulation capabilities when measured at rest and in response to emotion evocation (Beauchaine, Reference Beauchaine2015). RSA is an index of parasympathetic nervous system activity, an important component of the stress response system, and is derived from the ebb and flow of heart rate over the course of respiration (Porges, Reference Porges2007). Generally, a profile of high RSA levels while at rest and a modest withdrawal of RSA in response to acute challenge or stress (i.e., RSA reactivity) suggests a capacity to react to environmental demands flexibly (e.g., El-Sheikh & Erath, Reference El-Sheikh and Erath2011; Porges, Reference Porges2007, Reference Porges2011).

Accordingly, high resting RSA and modest RSA reactivity are thought to protect individuals against the effects of early adversity (El-Sheikh & Hinnant, Reference El-Sheikh and Hinnant2011; Porges, Reference Porges2007). However, several findings are at odds with this idea, suggesting a more complex picture. For example, Conradt, Measelle, and Ablow (Reference Conradt, Measelle and Ablow2013) reported that high resting RSA was associated with elevated behavior problems for infants who had experienced high levels of adversity, but high resting RSA was associated with low levels of behavior problems for infants reared in supportive environments. In addition, high resting RSA has been associated with shorter delay of gratification among children living in poverty but has been associated with longer delay of gratification among children of middle-class families (Sturge-Apple et al., Reference Sturge-Apple, Suor, Davies, Cicchetti, Skibo and Rogosch2016). As a result, developmental theorists posit that an interactional model of risk, including biological and environmental factors, may be most appropriate for understanding the development of externalizing problems within the context of early adversity.

One such theory, the diathesis-stress model, suggests that individuals reared in adverse environmental conditions will exhibit poorer functioning than individuals reared in low-risk settings only if the individuals also have a biological vulnerability (e.g., Sameroff, Reference Sameroff and Mussen1983). Differential susceptibility theories such as biological sensitivity to context theory and the adaptive calibration model (ACM) suggest that some children exhibit particular sensitivity to both adverse environmental conditions and resource-rich environments (e.g., Belsky & Pluess, Reference Belsky and Pluess2009; Boyce & Ellis, Reference Boyce and Ellis2005; Del Guidice, Ellis, & Shirtcliff, Reference Del Giudice, Ellis and Shirtcliff2011; Ellis & Boyce, Reference Ellis and Boyce2008; Ellis, Boyce, Belsky, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & van IJzendoorn, Reference Ellis, Boyce, Belsky, Bakermans-Kranenburg and van IJzendoorn2011). The ACM further proposes that the quality and nature of the environment shapes the stress response system in ways that promote adaptation to specific environmental conditions (Del Guidice et al., Reference Del Giudice, Ellis and Shirtcliff2011). In this theoretical framework, safe rearing environments and dangerous rearing environments are thought to lead to highly reactive stress response systems. In safe and supportive environments, greater reactivity may promote social learning and engagement. In contrast, in dangerous and unpredictable contexts, greater reactivity may promote defensive behaviors (i.e., “fight or flight”). Thus, a highly responsive system may index a child's sensitivity to environmental input “for better and for worse,” leading to negative outcomes only in adverse contexts but promoting positive outcomes in enriching contexts.

Of particular relevance to the present study, ACM researchers propose that severe or traumatic experiences such as maltreatment may lead to low stress reactivity (but perhaps only for males; Del Guidice et al., Reference Del Giudice, Ellis and Shirtcliff2011; Ellis, Oldehinkel, & Nederhof, Reference Ellis, Oldehinkel and Nederhof2017). In initial empirical evaluations of the ACM, negative family relationships and high levels of psychosocial stress predicted both high and low reactivity patterns (“vigilant” and “unemotional” profiles; Del Giudice, Hinnant, Ellis, & El-Sheikh, Reference Del Giudice, Hinnant, Ellis and El-Sheikh2012; Ellis et al., Reference Ellis, Oldehinkel and Nederhof2017), highlighting a need for further research to determine the impact of specific early adverse experiences on the developing stress response system. There is currently limited empirical data available to evaluate these models in the context of maltreatment.

In particular, research examining interactions between children's RSA activity and exposure to child maltreatment is sparse, and the findings are mixed. Gordis, Feres, Olezeski, Rabkin, and Trickett (Reference Gordis, Feres, Olezeski, Rabkin and Trickett2010) reported that maltreatment was associated with elevated aggression among adolescent boys with higher resting RSA (but not higher RSA reactivity to watching conflict video clips). These researchers did not find a main effect of maltreatment on children's RSA at rest or in response to the video clips. A separate study identified RSA reactivity, rather than resting RSA, as a moderator of maltreatment among preschoolers (Skowron, Cipriano-Essel, Gatzke-Kopp, Teti, & Ammerman, Reference Skowron, Cipriano-Essel, Gatzke-Kopp, Teti and Ammerman2014). In this study, maltreatment was associated with poor inhibitory control among preschoolers with high RSA reactivity to a parent–child challenge task (i.e., low task RSA). Again, a main effect of maltreatment on children's RSA was not detected. Cipriano, Skowron, and Gatzke-Kopp (Reference Cipriano, Skowron and Gatzke-Kopp2011) reported that neither RSA at rest nor RSA reactivity to a variety of emotional, cognitive, and social challenge tasks moderated the impact of living in high-violence households for emotional problems among preschoolers. Although living in a high-violence household is not necessarily a form of maltreatment, it may approximate the effects of maltreatment through repeated exposure to threat or fear in the home. Consistent with the other studies reviewed here, violence exposure was not significantly related to children's RSA in this study. In summary, there is some evidence that RSA activity may moderate the effects of maltreatment on the development of externalizing problems, but evidence for a main effect of maltreatment on children's RSA is lacking.

Several limitations in the current literature make it difficult to determine whether RSA at rest and RSA reactivity to emotionally challenging situations interact with maltreatment to predict externalizing behaviors. First, very few studies have examined RSA activity as a moderator of the effects of maltreatment specifically on externalizing behavior. Ellis et al. (Reference Ellis, Boyce, Belsky, Bakermans-Kranenburg and van IJzendoorn2011) argued that research with samples that vary in risk exposure, including children exposed to more extreme forms of adversity such as maltreatment, are greatly needed. Second, the available research findings are mixed. Although one possible explanation for this is that a true effect does not exist, another possibility is that the effects systematically vary as a result of the different types of tasks. Researchers have measured RSA reactivity to a variety of different tasks, and RSA reactivity is thought to be task specific (Beauchaine, Reference Beauchaine2015). Measuring RSA reactivity to an emotionally evocative task is consistent with current methodological recommendations for developmental psychopathological research (Beauchaine, Reference Beauchaine2015).

It is also important to note that although previous studies have included maltreated samples in early childhood and adolescence, it is unclear how these relations may unfold for a maltreated sample during middle childhood. Middle childhood is an important developmental period in which to study the effects of early adversity on externalizing behavior for three primary reasons. First, clinically significant externalizing behaviors (e.g., oppositional defiant disorder and aggression) peak during the middle childhood period (e.g., Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Jin, Merikangas and Walters2005). Second, middle childhood is characterized by rapid growth in self-regulation (Best & Miller, Reference Best and Miller2010), which may be reflected in physiological indicators of regulation and how they relate to behavior problems. Third, children's stress response systems may shift during the middle childhood period as children focus on peers, learning, and self-regulation, making middle childhood an important developmental “switch point” in prominent theoretical work (Del Guidice et al., Reference Del Giudice, Ellis and Shirtcliff2011).

Current Study

The primary goal of the current study was to examine RSA in middle childhood as a moderator of the association between early risk for maltreatment and later externalizing problems among school-age children. Analyses included two samples of children matched on age and gender but who differed with respect to environmental risk: a sample recruited by referral from CPS due to risk of maltreatment and a comparison sample recruited from local community centers. A measure of cumulative environmental risk was included in the analyses to attempt to isolate the effect of CPS involvement from other environmental risk factors. Although we expected that cumulative risk would be positively related to externalizing problems in middle childhood, we hypothesized that CPS involvement would uniquely relate to externalizing behavior problems above and beyond the effect of cumulative risk.

Our hypotheses were informed by diathesis-stress and differential susceptibility models, although our data are insufficient to formally evaluate these models (e.g., our data do not capture the full possible range of environmental quality; see Roisman et al., Reference Roisman, Newman, Fraley, Haltigan, Groh and Haydon2012). Based on these theoretical frameworks as well as other evidence suggesting that high RSA at rest and high RSA reactivity may be associated with increased externalizing problems for maltreated children and adolescents (Gordis et al., Reference Gordis, Feres, Olezeski, Rabkin and Trickett2010; Skowron et al., Reference Skowron, Cipriano-Essel, Gatzke-Kopp, Teti and Ammerman2014), we hypothesized that a history of CPS involvement would be associated with elevated externalizing problems for children exhibiting high RSA at rest and high levels of RSA withdrawal in response to frustration (which both diathesis-stress and differential susceptibility models would predict). Given the lack of evidence that maltreatment has a main effect on children's RSA, we did not hypothesize that we would observe a main effect of maltreatment, but we planned to explore potential associations between maltreatment and RSA in descriptive analyses.

Method

Participants

Participants were drawn from the middle childhood wave of a longitudinal study assessing the efficacy of a parenting intervention delivered in infancy, Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-up (ABC; Dozier & Bernard, Reference Dozier and Bernard2019). The full sample included 174 children. Children were not included in the current analyses if their physiological data were not available (n = 39) or if information about children's externalizing behavior problems were not collected (n = 12). As a result, the sample size for this study was 123.

Of the included children, about two-thirds (n = 75) were recruited in infancy by referral from CPS due to risk for maltreatment and were randomly assigned to receive either the ABC intervention in infancy (n = 31) or a control intervention (n = 44). Of these 75 children, 6 children completed the 9-year-old assessment with caregivers other than those who received the original intervention. Of those 6 children, 2 children completed the 9-year-old assessment with their biological fathers, 2 children completed the assessment with their aunts, 1 completed the assessment with her maternal grandmother, and 1 completed the visit with a biologically unrelated legal guardian. A non-CPS-referred comparison sample was recruited in middle childhood, and children were matched to the CPS-referred sample on age, race, and gender (although race matching was not preserved in the current subsample, as described below). Parents confirmed that their children did not have any CPS involvement through self-report. In the present study, 48 children were in the comparison sample. When children were about 9 years old (M = 9.46, SD = 0.34), parents reported on children's behavior problems, and children's autonomic nervous system data were recorded while children were at rest and during a frustration task. All procedures were approved by the institutional review board.

Based on parent report, most children were African American (60.2%) or multiracial (13.8%), and 13.0% were White. In addition, about one-fifth (21.1%) of the children were Latino. In this subsample, there was a significantly greater proportion of White children in the comparison sample than in the CPS-referred sample, χ2 (1, N = 123) = 7.17, p = .01, Φ = .24. The groups did not significantly differ by proportion of Latino children, χ2 (1, N = 123) = 0.27, p = .60. Φ = .05, or by gender, χ2 (1, N = 123) = 0.00, p = .99, Φ = .001.

Parents also reported on their educational attainment and socioeconomic status at the time of the 9-year-old assessment. Approximately one-third (35.6%) of the CPS-referred parents had not completed high school or received their GED, relative to only 2% of parents from the comparison sample, χ2 (1, N = 119) = 17.99, p < .001, Φ = .39. In addition, about three-quarters (75.3%) of the CPS-referred parents reported receiving financial support from government programs, compared to 8.8% of parents from the comparison sample, χ2 (1, N = 118) = 49.18, p < .001, Φ = .65.

Procedures

Externalizing problems

Parents reported on children's behavior problems using the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL/6-18; Achenbach & Rescorla, Reference Achenbach and Rescorla2001). Parents were asked to rate the extent to which their children engaged in 111 emotional and behavior problems on a 3-point scale from 0 (not true) to 2 (very true or often true); 2 items related to self-harm and suicidality were removed from questionnaires. For the present study, the externalizing subscale was calculated by taking the sum of the rule-breaking items (17 items) and the aggressive behavior items (18 items). Internal reliability for the externalizing subscale was excellent (α = .91). Of the 135 children with usable RSA data, 12 were missing CBCL data, but the proportion of children missing CBCL data was similar in the CPS-referred group and the comparison group, χ2 (1, N = 135) = 2.34, p = .13, Φ = .13.

Frustration task

Children completed a frustration task while autonomic nervous system data were continuously recorded. The frustration task was adapted from the Impossibly Perfect Circles task (Goldsmith, Reilly, Lemery, Longley, & Prescott, Reference Goldsmith, Reilly, Lemery, Longley and Prescott1999). Children first completed a 2-min resting baseline during which they viewed a nature image while listening to peaceful sounds. After this baseline, the frustration task formally began. In this task, children were given one small paper maze at a time, and a research assistant asked children to complete it perfectly. After each maze, the research assistant provided a critique in a neutral tone (e.g., “That one is too crooked. Try another one.”). After 3.5 min, the research assistant made an excuse to leave the room and left a stack of mazes so that the children could continue trying to complete the perfect maze while the research assistant was out of the room. After 1 min, a second research assistant entered the room to conduct a brief interview about the children's feelings during the critique. The interview lasted about 1 min. Altogether, the various elements of this task required that the child persist in completing a perfect maze with and without an adult present. The child was not released from these task demands until the completion of the interview. At that time, the child was asked to complete one final maze, and the first research assistant returned to provide praise for this maze.

About one-third of the children were asked to complete perfect circles instead of perfect mazes. The task was changed from circles to mazes because the circle protocol was administered at the previous lab visit, and some children indicated that they remembered the task. In addition, these same children completed a portion of an additional emotion regulation task (the Disappointing Gift; Cole, Reference Cole1986) between the baseline and the frustration task. Because the task was only completed with a small subsample of participants, those data were not included in the analyses. As described below, task version was considered as a covariate because it was significantly associated with RSA during the challenge (see Table 1 for correlations), and because the proportion of CPS-referred children who completed the perfect circles task (23 of 75) was larger than the proportion of the non-CPS-referred children who had this task (2 of 48), χ2 (1, N = 123) = 12.69, p < .001, Φ = .32.

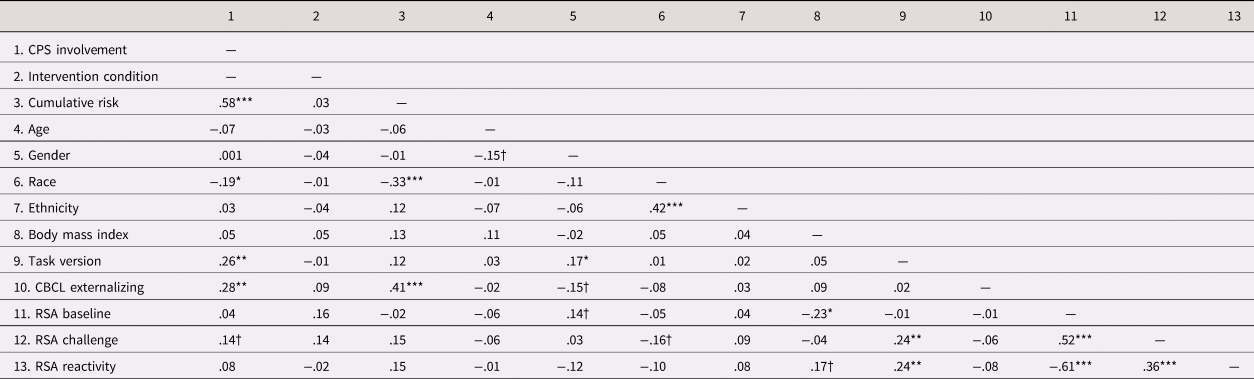

Table 1. Correlations of study variables and covariates

Note: For the CPS involvement variable, the CPS-referred group was dummy coded as “1” and the comparison group was dummy coded as “0.” For the intervention condition variable, the Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-up group was dummy coded as “1” and the control group was dummy coded as “0.” For the gender variable, male participants were dummy coded as “0” and female participants were dummy coded as “1.” For the race variable, Caucasian participants were dummy coded as “1” and all other participants were coded as “0.” For the ethnicity variable, Hispanic participants were dummy coded as “1” and non-Hispanic participants were dummy coded as “0.” For the task version variable, the perfect circles task was dummy coded as “1” and the perfect mazes task was dummy coded as “0.” CPS = Child Protective Services. CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist. RSA = Respiratory sinus arrhythmia. †p < .10. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Autonomic nervous system data collection, cleaning, and reduction

Software and hardware from the James Long Company were used for data acquisition, cleaning, and processing (James Long Company, Caroga Lake, NY, USA). RSA was calculated from heart rate and respiration data. Heart rate data were collected using two disposable electrocardiography electrodes placed on the rib cage (one on the left and one on the right) and one grounding electrode placed on the chest (a bipolar configuration). Respiration data were collected using a pneumatic bellows belt fastened around the midsection.

Data were collected at a sampling rate of 1,000 readings per second, using James Long equipment for amplification and digitization. The software algorithm identified heartbeats, calculated interbeat intervals (IBIs) as the difference in milliseconds between the beats, and identified IBIs with unusual values for visual verification or correction. Misidentified heartbeats were manually corrected. Consistent with previous work with children in middle childhood (Woody, Feurer, Sosoo, Hastings, & Gibb, Reference Woody, Feurer, Sosoo, Hastings and Gibb2016), nine children's electrocardiography data were excluded from analyses because 10% or more of the heart beats required manual correction. The data for seven additional children were excluded due to missing respiration data, and the data for six other children were missing due to experimenter error. Data were missing for eight children because they completed a home visit instead of a lab visit, and data were missing for nine children due to a fire that occurred in the lab building, which destroyed the physiological equipment before data collection was completed. Children who were missing RSA data did not differ by sample, χ2(1, N = 174) = 0.20, p = .65, Φ = .03.

RSA was estimated using the peak-to-valley method, which quantifies the difference in IBIs during respiratory inspiration and expiration. Average RSA was calculated for each segment of the frustration task, abbreviated as RSAbaseline, RSAcritique, RSAalone, and RSAinterview. The skewness values for these four epochs were within or near acceptable limits (between 0.66 and 2.13). RSA values during the three challenge epochs were significantly correlated both in bivariate correlations (rs between .63 and .79; ps < .001) and in partial correlations controlling for baseline RSA (rs between .67 and .77; ps < .001). Due to the high statistical overlap between the epochs as well as the overlap in task demands between the epochs, these epochs were averaged to create a single composite score, RSAchallenge. The skewness of this variable was within acceptable limits (skewness statistic = 1.33). Finally, RSAreactivity was calculated by subtracting RSAbaseline from RSAchallenge. When calculated this way, negative values of RSAreactivity indicate RSA withdrawal from baseline to the challenge, and positive values indicate RSA augmentation.

Cumulative risk

A cumulative risk score was created to isolate the effect of early CPS involvement from other cumulative environmental risks. Five variables were included based on previous work with this sample (Bernard, Simons, & Dozier, Reference Bernard, Simons and Dozier2015): child racial/ethnic minority status (non-White), parental education (less than GED), family financial security (receiving financial support from government program), parental depression (1 SD above the mean on the Brief Symptom Inventory depression subscale; Derogatis & Spencer, Reference Derogatis and Spencer1982), and adolescent parenthood (under age 18 at the time of the child's birth). All indicators were collected by parent report at the 9-year-old laboratory visit. Each indicator was dichotomized, with a score of 1 indicating the presence of that risk factor and a score of 0 indicating the absence of that risk factor and summed to create the cumulative risk score. Although cumulative risk scores had a possible range of 0 to 5, the range in the current sample was 0 to 4 (M = 1.79, SD = 1.01).

Plan of analysis

Hierarchical regression models were used to test RSAbaseline, RSAreactivity, and CPS involvement as predictors of children's externalizing problems. In addition, the interaction between each RSA variable and CPS involvement was tested to assess whether the relation between CPS involvement (a proxy for risk of maltreatment) and externalizing problems depended on RSA. Finally, in order to determine whether effects of CPS involvement were due to cumulative risk more generally rather than maltreatment in particular, the analyses were rerun to include cumulative risk score as an additional covariate.

Results

Preliminary analyses

Descriptive statistics

Zero-order correlations and descriptive statistics of study variables are presented in Tables 1 and 2. CPS involvement was associated with race (there were significantly more White children in the comparison group than in the CPS-referred group), and with task version (CPS-referred children were more likely to have completed the perfect circles version due to the timing of recruitment of the comparison sample). In addition, CPS involvement was positively associated with externalizing problems, and girls had marginally fewer externalizing problems than boys in the full sample. CPS-referred children had significantly higher cumulative risk scores than comparison children, t (140.09) = 8.98, p < .001. In the full sample, externalizing problems were not significantly related to any of the RSA variables. Finally, the CPS-referred group and the comparison group did not significantly differ on RSAbaseline, t (133) = 0.49, p = .62, or RSAreactivity, t (133) = 0.87, p = .87, and cumulative risk was not significantly correlated with RSAbaseline (r = –.02, p = .87) or RSAreactivity (r = .15, p = .10).

Table 2. Means and standard deviations of study variables by sample

Note: CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist. RSA = Respiratory sinus arrhythmia.

Paired samples t tests indicated that children experienced a significant RSA decrease from baseline to the challenge, t (135) = 5.11, p < .001, suggesting that the frustration task effectively elicited an RSA response from children. Descriptively, although most children exhibited a decrease in RSA (69.9%; negative RSAreactivity score), a minority of children showed no observable change in RSA (12.2%; RSAreactivity score of 0) or exhibited an increase in RSA from baseline to challenge (i.e., RSA augmentation, or positive RSAreactivity score; 17.9%).

Covariates

Based on zero-order correlations between study variables as well as previous research findings (e.g., El-Sheikh et al., Reference El-Sheikh, Kouros, Erath, Cummings, Keller and Staton2009), the following variables were considered as covariates: intervention condition, age, gender, body mass index, and task version. Of note, there were no significant zero-order correlations between any of these potential covariates and externalizing problems in this sample. In addition, potential interactive effects between these covariates and primary study variables were explored. However, none of the potential covariates produced significant interactive effects. Models exploring covariates are presented in the online-only supplemental material. Further, three-group models were conducted in order to explore potential intervention effects, but significant main or interactive effects of intervention on externalizing problems were not detected. Thus, focal models are presented below without covariates.

Testing moderation

Resting RSA

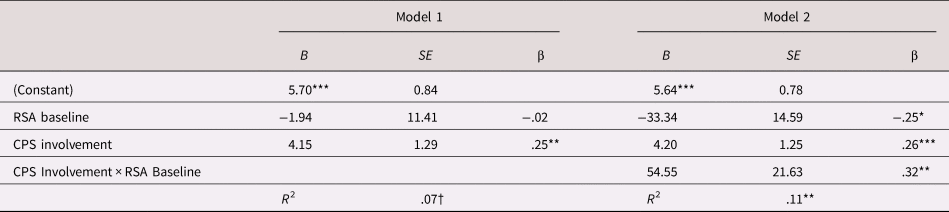

To test whether resting RSA moderated the association between CPS involvement and externalizing problems, hierarchical multiple regression was conducted (see Table 3). RSAbaseline was mean-centered prior to analyses to aid interpretation of results. CPS involvement was a significant predictor of externalizing problems in Step 1 (β = .25, p = .001) and in Step 2 (β = .26, p < .001; i.e., after the addition of the interaction term). RSAbaseline was not a significant predictor of externalizing problems in Step 1 (β = –.02, p = .87), but it was a significant predictor in Step 2 (β = –.25, p = .02), such that higher resting RSA was associated with fewer externalizing problems. Finally, the interaction of RSAbaseline and CPS involvement was significant (β = .32, p = .009).

Table 3. Predicting externalizing problems from resting RSA and CPS involvement

Note: For the CPS Involvement variable, the CPS-referred group was dummy coded as “1” and the comparison group was dummy coded as “0.” CPS = Child Protective Services. †p < .1. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

In order to interpret the interaction between RSAbaseline and CPS involvement, simple slopes were calculated. Figure 1 depicts these results. Simple slopes indicated that for children who exhibited average or above average resting RSA, CPS involvement was associated with elevated levels of externalizing problems (mean: B = 4.20, p = .001; 1 SD above the mean: B = 7.65, p < .001). For children who exhibited low resting RSA (1 SD below the mean), CPS involvement was not significantly associated with externalizing problems (B = 0.74, p = .71). These simple slopes were consistent across analyses testing the impact of potential covariates. Scatterplots of externalizing problems by CPS involvement and RSA are included in the online-only supplemental material. Additional simple slope analyses (not pictured) indicated that the associations between resting RSA and externalizing problems were significant and positive for both groups (CPS-referred B = 58.74, p = .01; comparison B = 4.20, p = .001). However, the pattern of simple slopes by sample group was not consistent across models with other covariates, and so caution may be warranted in interpreting these results.

Figure 1. Simple slopes of the association between CPS involvement and externalizing problems as a function of resting RSA levels. High resting RSA is defined as 1 SD above the mean, average RSA reactivity is defined as the mean, and low RSA reactivity is defined as 1 SD below the mean. ns p > .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

RSA reactivity

A separate model was run to test whether RSA reactivity interacted with CPS involvement to predict externalizing problems (see Table 4). This approach was chosen rather than combining the two interactions into one larger model due to collinearity of RSAbaseline and RSAreactivity. However, RSAbaseline was still included as a covariate. RSAreactivity was mean-centered prior to analyses. In the first step of the model, RSAbaseline was entered as a control variable, but it was not as significant predictor of externalizing problems (β = –.01, p = .92). In the second step, CPS involvement and RSAreactivity were entered as predictors. In this model, only CPS involvement (β = .28, p < .001) was a significant predictor; neither RSAreactivity (β = –.18, p = .20) nor RSAbaseline (β = –.14, p = .24) were significant. In the final step, the interaction term of CPS involvement and RSAreactivity was entered. The interaction term was a significant predictor of externalizing problems (β = –.41, p = .02). CPS involvement remained a significant predictor (β = .26, p = .001), and RSAbaseline and RSAreactivity remained nonsignificant.

Table 4. Predicting externalizing problems from RSA reactivity and CPS involvement

Note: For the CPS involvement variable, the CPS-referred group was dummy coded as “1” and the comparison group was dummy coded as “0.” CPS = Child Protective Services. †p < .1. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Again, in order to interpret the significant interaction between CPS involvement and RSAreactivity, simple slopes were calculated and plotted (see Figure 2). Simple slopes were first calculated to estimate the association between CPS involvement on externalizing problems at high, average, and low levels of RSA reactivity. For children who exhibited average or greater than average RSA withdrawal (i.e., RSA decrease from baseline to challenge), CPS involvement was associated with elevated levels of externalizing problems (average B = 4.24, p = .001; high B = 7.93, p < .001). For children who exhibited low RSA reactivity or RSA increase, CPS involvement was not significantly associated with externalizing problems (B = 0.55, p = .82). This pattern of results was consistent across analyses testing potential covariates. Scatterplots of externalizing problems by CPS involvement and RSA are included in the online-only supplemental material.

Figure 2. Simple slopes of the association between CPS involvement and externalizing problems as a function of RSA reactivity. High RSA reactivity is defined as 1 SD below the mean (i.e., greater withdrawal, or decrease from baseline, than average), average RSA reactivity is defined as mean withdrawal, and low RSA reactivity is 1 SD above the mean (i.e., less withdrawal than average, or RSA increase from baseline to challenge). ns p > .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Due to concerns that task version may be a confound resulting from significant differences in task version across groups, exploratory analyses were conducted excluding the children who received the perfect circles task (adjusted n = 98). Although the interaction term of this model was not significant (B = –0.21, p = .12), likely due to reduced power, the simple slopes for this subsample revealed that the slope remained steepest for children with high RSA reactivity. Simple slope values were similar to those for the full sample for children (low B = 2.96, p = .18; average B = 5.57, p < .001; high B = 8.18, p < .001).

Additional simple slope analyses (not pictured) were calculated to test whether the association between RSA reactivity on externalizing problems differed by group. Associations between RSA reactivity and externalizing problems were in the opposite direction for each group (CPS-referred B = –63.10, p = .03; comparison B = 4.24, p = .001). Again, the estimates and significance level for simple slopes by sample were inconsistent across models examining potential covariates, and so caution is warranted when interpreting these results.

Cumulative risk

Additional models were run to test whether the inclusion of the cumulative risk score in the models changed the pattern of results, and to investigate whether similar effects would be observed when CPS involvement was replaced with the cumulative risk score. Overall, cumulative risk seemed to capture much of the main effect of CPS involvement on externalizing problems but did not explain the interaction between CPS involvement and the RSA variables in predicting externalizing problems. Following primary analyses, as a robustness check, exploratory analyses were conducted excluding CPS-referred children who had cumulative risk scores beyond the range observed in the non-CPS-referred group. As the pattern of results did not change, we present analyses with the full sample here.

The model testing RSAbaseline as a moderator was run again with cumulative risk and an interaction term between cumulative risk and RSAbaseline included as additional predictors. In this model, risk was a significant predictor of externalizing problems (β = .33, p < .001), but the main effect of CPS involvement on externalizing problems was no longer significant (β = .07, p = .41). The interaction of RSAbaseline and CPS involvement remained significant (β = .36, p = .001). In contrast, cumulative risk did not interact with RSAbaseline to significantly predict externalizing problems (β = –.14, p = .34).

Next, the model testing RSAreactivity as a moderator was run again with the addition of cumulative risk and an interaction term between cumulative risk and RSAreactivity as predictors. In this model, cumulative risk was again a significant predictor of externalizing problems (β = .36, p < .001), whereas CPS involvement was not (β = .06, p = .52). However, the interaction between CPS involvement and RSAreactivity remained significant (β = –.50, p = .004). In contrast, cumulative risk did not interact with RSAreactivity to significantly predict externalizing problems (β = .23, p = .21).

Discussion

In the present study, we found that the longitudinal association between CPS involvement during infancy and externalizing behavior problems during middle childhood was conditional on children's RSA levels while at rest and in response to a frustration task. Specifically, CPS involvement predicted elevated externalizing problems for children who had average to high RSA at rest and/or average to high RSA withdrawal to a frustration task. For children who had low resting RSA or low RSA withdrawal (or RSA increase) to the frustration task, CPS involvement was not significantly related to externalizing problems. Similar to previous work (e.g., Gordis et al., Reference Gordis, Feres, Olezeski, Rabkin and Trickett2010; Skowron et al., Reference Skowron, Cipriano-Essel, Gatzke-Kopp, Teti and Ammerman2014), we did not detect a significant main effect of CPS involvement on children's baseline RSA levels or RSA responses to the frustration task.

These results are consistent with recent theory that posits that excessive RSA reactivity to negative emotion evocation indexes emotion dysregulation and is associated with elevated risk for various psychopathologies, especially among children with a history of early adversity (Beauchaine, Reference Beauchaine2015). Our results mirror those reported by Skowron et al. (Reference Skowron, Cipriano-Essel, Gatzke-Kopp, Teti and Ammerman2014), which showed that maltreatment was associated with poor inhibitory control among preschoolers with high RSA reactivity. With regard to resting RSA, the present study demonstrated that high resting RSA exacerbated the effect of CPS involvement on externalizing problems, consistent with some previous research (Gordis et al., Reference Gordis, Feres, Olezeski, Rabkin and Trickett2010). Of note, our findings diverge from other research and theory, which suggest that high RSA reactivity and high RSA at rest in particular may reduce the risk that youth develop externalizing behaviors (El-Sheikh, Harger, & Whitson, Reference El-Sheikh, Harger and Whitson2001; El-Sheikh & Whitson, Reference El-Sheikh and Whitson2006; Porges Reference Porges2007, Reference Porges2011).

Both diathesis-stress and differential susceptibility models predict that, in the context of environmental stress, children who exhibit biological vulnerability or susceptibility (here, high RSA at rest and high RSA reactivity) will exhibit less competent behavioral outcomes than children who do not have this biological vulnerability. However, these models diverge with regard to children exposed to highly supportive and well-resourced rearing environments. The present study is limited in its capacity to disentangle whether risk for externalizing behavior is best characterized by diathesis-stress or differential susceptibility (biological sensitivity to context or ACM) models for several reasons. In order to fully compare these theoretical models, it is important that the sample spans the full range of environmental quality (Roisman et al., Reference Roisman, Newman, Fraley, Haltigan, Groh and Haydon2012). The present study likely only captured part of this range, from extreme adversity to average quality. Further, limited information is available about the nature of these children's early caregiving experiences, particularly for the non-CPS-referred sample. Such information is likely necessary to determine whether children in our sample may fit into the profiles predicted by the ACM.

Although RSA activity shows moderate stability over time (e.g., El-Sheikh, Reference El-Sheikh2005), evidence suggests that early caregiving experiences influence children's developing autonomic nervous systems (Del Giudice et al., Reference Del Giudice, Hinnant, Ellis and El-Sheikh2012; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Deardorff, Davis, Martinez, Eskenazi and Alkon2017; Tabachnick, Raby, Goldstein, Zajac, & Dozier, Reference Tabachnick, Raby, Goldstein, Zajac and Dozier2019). However, consistent with several previous studies examining effects of maltreatment (Gordis et al., Reference Gordis, Feres, Olezeski, Rabkin and Trickett2010; Skowron et al., Reference Skowron, Cipriano-Essel, Gatzke-Kopp, Teti and Ammerman2014), we did not detect an association between CPS involvement and children's RSA. One reason for this may be due to the heterogeneity within this sample, with some children likely experiencing “dangerous/unpredictable environments” and others experiencing “severe/traumatic stress.” Because the ACM predicts that these two types of environmental exposures would have opposite effects on the developing stress response system (Del Giudice, Reference Del Giudice, Ellis and Shirtcliff2011), collapsing these children into one group may obscure effects. We are further limited because we did not measure children's RSA prior to middle childhood. As a result, it was not possible to evaluate whether children experienced different developmental trajectories of RSA immediately after their early experiences or whether RSA at different ages may also moderate the consequences of early maltreatment for later externalizing behavior problems. Thus, future studies should strive for comprehensive and prospective measurement of children's early caregiving environment and RSA activity to adequately unpack trajectories of RSA activity and externalizing behavior in relation to a wide range of early caregiving experiences.

General Discussion

Experiencing maltreatment in infancy may be qualitatively different from other forms of environmental stress because maltreatment represents fundamentally inadequate caregiving at a time of life when children are entirely dependent on parental care. In the present study, the significant interaction between CPS involvement and RSA activity was robust to the inclusion of cumulative risk as a covariate. Further, the interaction of cumulative risk and RSA activity was not significant. Thus, there appears to be a unique association between CPS involvement and externalizing problems that is not explained by overall high risk for exhibiting externalizing symptoms. Findings reinforce the importance of testing biobehavioral theories of the origins of externalizing behavior problems among children exposed to maltreatment, which may have unique effects beyond cumulative risk.

The present study has significant strengths. One major strength is the inclusion of two samples that vary with respect to CPS involvement and cumulative risk. Including the two samples allowed for analyses disentangling the effects of risk for maltreatment specifically and general cumulative risk. In addition, the present study applied rigorous physiological methodology by measuring RSA reactivity in response to a negative emotional task (Beauchaine, Reference Beauchaine2015). Finally, the present study extends previous research on RSA as a moderator of early adversity by focusing on children in middle childhood.

There are also several important limitations of the current study that suggest directions for future research. The current study assessed RSA activity at one point in time (middle childhood) and in response to one emotional situation. Further, although several indicators of early adversity were available for the current study, there are limitations to these data. Detailed CPS records were unfortunately not available, so the present study cannot determine whether effects may also depend on reason for CPS involvement. Maltreatment subtype may be important in describing the development of externalizing problems (Manly, Kim, Rogosch, & Cicchetti, Reference Manly, Kim, Rogosch and Cicchetti2001), and future studies should include this information if possible. A further limitation is the use of parent-reported behavior problems as our outcome. Parents may have reporting biases, and parents from different populations may interpret survey items differently. Given that the CPS-referred group exhibited a greater range of scores on the CBCL than the non-CPS-referred group in the present study, it is possible that there is measurement noninvariance between the groups in the current study. Although the CBCL is widely used and has been validated across cultures (Gross et al., Reference Gross, Fogg, Young, Ridge, Cowell, Richardson and Sivan2006; Ivanova et al., Reference Ivanova, Achenbach, Dumenci, Rescorla, Almqvist, Weintraub and Döpfner2007; Rescorla et al., Reference Rescorla, Achenbach, Ivanova, Dumenci, Almqvist, Bilenberg and Erol2007), the use of observational measures of behavior problems in addition to parent-reported problems would strengthen future studies. Further, the relatively small sample size limited our statistical power to comprehensively test additional sociodemographic moderators.

An additional limitation is the alteration of the frustration paradigm in the middle of the study, which resulted in the CPS-referred group disproportionately performing the perfect circles task. Of note, although it is potentially informative that including task version as a covariate did not change the pattern of results, it is difficult to statistically control for the effects of task version due to the low incidence of the perfect circles task in the non-CPS-referred group. In addition, task version was correlated with our RSA reactivity variable, indicating that the potential role of task version in analyses deserves careful consideration. Although it is reassuring that the pattern of results of RSA reactivity analyses converge with those of resting RSA analyses (which were not affected by the alteration of the frustration paradigm), caution is warranted in interpreting our findings regarding RSA reactivity in particular. Due to the correlation between RSA at rest and RSA in response to challenge, it is difficult to determine whether both variables are unique moderators.

Finally, effects of the ABC intervention on children's RSA were not observed in the present study. However, ABC intervention effects have been observed for children's RSA during a paced breathing baseline with their parents and during a challenging parent–child discussion activity (Tabachnick et al., Reference Tabachnick, Raby, Goldstein, Zajac and Dozier2019). One likely explanation for the differences in findings is the differences in task demands. Specifically, the parent–child interactions involved discussing an emotionally sensitive topic with an attachment figure, whereas the frustration task involved regulating feelings of anger while interacting with a stranger. This pattern of results across tasks highlights the importance of careful task selection. In future studies, researchers may wish to record autonomic functioning during a variety of tasks to determine the boundary conditions of a given effect.

In sum, the present study demonstrated that RSA at rest and in response to frustration moderate the association between CPS involvement in infancy and externalizing problems in middle childhood. Findings indicate that maltreatment is associated with increased risk for behavior problems but only among children who exhibit average to high resting RSA at rest and average to high RSA withdrawal in response to frustration. In other words, it seems that there are children for whom experiencing early maltreatment may not confer significant risk for the development of behavior problems. These findings highlight the importance of biological regulation for understanding relations between early adversity and the development of externalizing behavior problems.

Supplementary Material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579420000152.

Financial support

This work was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grant R01MH074374.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.