Of all the paper ephemera produced in eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Britain, high art engravings have long attracted attention from scholars and collectors.Footnote 1 In a sub-genre of tickets, theatre and elite entertainments predominate.Footnote 2 But when it comes to survivals from the period, both are matched by the humble Methodist ticket, which from 1741 was issued quarterly to members as a testimonial to their religious conduct. This persistence is a reflection of the number produced, in the millions by 1850.Footnote 3 Other types of ticket were also printed in considerable quantities: turnpike tickets, seamen's tickets (a type of pay warrant), and the largest category of all, lottery tickets, but their lower survival rates point to the significance of keeping practices, where Methodist habits were distinctive.

This article explores the origin and spread of tickets primarily within British Methodism, but also noting its trans-oceanic contexts. It highlights the importance of apparently inconsequential objects in shaping experience and knowledge. It traces the processes through which tickets were made, issued, displayed, exchanged, and stored. Ordinary women and men learnt through Methodism the potential for tickets, and paper more generally, to initiate and regulate social relationships. In giving feelings a material form, the ticket embodied aspects of being, self, and belonging; it forged connections and identities. Early use illuminates eighteenth-century religious life and plebeian agency. Simultaneously, Methodist tickets unsettle an established narrative about the broader society in which they emerged, specifically the development of print and urban association.

Patterns of memory and memorialization are the second focus of this article. From the 1740s, Methodists saved and collected tickets. They gathered them into scrap-books, envelopes, and boxes. Historians of the movement then scrambled for complete sets. That urge to preserve finally deposited many of them in archives where tickets now sit alongside more familiar Methodist documentation, including class lists and circuit plans.Footnote 4 Such practices extended the lifecycle of the individual ticket and created the accidents of its survival, giving it new uses as an institutional resource. In recovering the dead, it acquired nostalgic value, but other capacities were lost and forgotten.

The Methodist ticket is a potentially rich historical prospect, in the sense that it falls between and straddles categories; it disappears in interesting ways. Modern Methodist historiography suggests how the ticket might be understood in relation to religious practice and movement-building, but has little to say about it explicitly. Its presence in the American colonies and the Caribbean is even more elusive.Footnote 5 Literature on the material culture of popular religion suggests one approach.Footnote 6 Ephemera studies offer a way of defining the form of the ticket, as insubstantial, short-lived, dispensable, and also persistent. They shed light on the jobbing printers who produced it, on the formation of a distinctive category of ephemeral print in the mid-eighteenth century, and on its subsequent collection.Footnote 7 We shall see how the Methodist case challenges orthodoxies and classifications, here as elsewhere. Methodist antiquarianism has supplied the most significant body of material, often structured as catalogues and authored in some instances by collectors themselves.Footnote 8 But these men's concerns make a poor match with connoisseurship, aesthetics, and enlightenment knowledge: neither their object (the ticket) nor their purpose (a religious history) conforms to an important strand in the literature on collecting. So while the first Methodist tickets emerged in a period that scholars associate with systematic collecting, characteristics of those eighteenth-century practices still define a field that excludes Methodist examples.Footnote 9 As for the habits of those who first saved the paper, they are poorly served by the critical elaboration of ‘collecting’ as a higher-order activity distinct from accumulation.Footnote 10 Studies informed by sociological and ethnographic approaches cover some of the ground discussed in this article, but their present-day examples are not always a good fit.Footnote 11 Psychoanalytic and philosophical approaches emphasize what the set does for the collector, rather than what the collection does to the item contained within it.Footnote 12 Actor-network theory gives the ticket ‘life’ and an agency suited to its capacity to flow and shape, but precisely what does that mean in a religious setting, where memory is suffused with providential thinking?Footnote 13 Memory studies have had relatively little to say about the world before 1800.Footnote 14 Work on eighteenth-century Britain, where the origins of the Methodist ticket lie, sets an interpretative agenda in relation to material objects, mobility, gender, emotion, and sociability, but again is largely oblivious of it.Footnote 15 In short, the Methodist ticket is an invisible presence in major historical and historiographical currents. What happens when it becomes visible?

I

While its history is underexplored, ticket use grew during the early modern period with a proliferation of specialized kinds mostly printed on paper and card, but also fashioned from other materials, including metal and bone. In timing, innovation, and popular exposure, this expansion parallels development of the administrative form.Footnote 16 Urban sociability, commerce, and print made an increasing proportion of the eighteenth-century population familiar with tickets, either through handling them – the pawnbroker's duplicate or ‘ticket’, for instance – or through indirectly knowing about them – such as the more specialized ‘Tyburn ticket’, a judicial reward that exempted the holder from parish office. While newspapers and coffee houses spread knowledge of and distributed tickets, tickets were not simply a metropolitan or urban phenomenon nor were they always monetized. Women and men, aristocrats, middling sort, and labourers, encountered these objects in a range of convivial and institutional settings, learning the conventions that set them to work. Everyday transactions and micro-politics involving tickets expanded earlier practices that expressed obligations and feelings through things, or used seals, certificates, and papers to underwrite identities. Tickets extended opportunities to give access, possession, information, social capital, and even chance a tangible form. In that shape, abstract qualities as well as material benefits could be exchanged, displayed, circulated, or released. Cumulatively over the course of the century, people found ways of using tickets to shape social life, to store information, to organize religious, military, and political organizations, to materialize relationships and trust.Footnote 17

Looking across the eighteenth-century range, from the elite assembly ticket to the beggar's or radical's version, certain patterns emerge. Tickets multiplied in contexts marked by mobility, social fluidity, expansion, and change. They created distinctive ways of relating to and managing other people, and of surviving, whether through legitimate or fraudulent acquisition. Through generations of trial and use, people learnt to associate tickets with relationships of exchange, belonging, and identity, until these habits became instinctive and transparent. At the same time, interactions around tickets could add layers of aesthetic, sensory, and emotional meaning that went beyond monetary or practical value. These responses ensured that some tickets were carefully kept long past their immediate purpose, until all such attributes were spent.Footnote 18

Methodists have a special part in this history. They were the first British religious group to deploy tickets as a central feature in their society, an experiment that gave tickets new properties, power, and movement. John Wesley recognized tickets’ potential in spiritual life, introducing them in 1741 to regulate worshippers in Bristol: ‘to those who were sufficiently recommended, tickets were given’.Footnote 19 From that date onwards, the ticket asserted order and authority.Footnote 20 What began in a moment of crisis in the religiously intense atmosphere of early Methodism was rapidly systematized into a quarterly process of examining and then separating ‘the precious from the vile’:

To each of those, of whose Seriousness and Good Conversation, I found no Reason to doubt, I gave a Testimony under my own Hand, by writing their Name on a Ticket prepared for that Purpose; Every Ticket implying as strong a Recommendation of the Person to whom it was given as if I had wrote at length, ‘I believe the Bearer hereof to be one that fears GOD and works Righteousness.Footnote 21

Methodist preaching was open, but entry into any meeting, including the emotionally charged ‘love-feast’ (a time of fervent prayer and fellowship), required a ticket.Footnote 22 It was a disciplinary device, a ‘quiet and inoffensive Method’ of excluding the ‘disorderly walker’: ‘He has no New Ticket … and hereby it is immediately known, That he is no longer of this Community.’Footnote 23 A means to administer an expanding movement, it was especially valuable in creating certainty and knowledge. For those who physically held a current ticket, it was a guarantee of belonging. It introduced them ‘into fellowship with one another, not only in one place, but in every place where any might happen to come’.Footnote 24 Early Methodists were mobile. The ticket was in motion, leaving a paper trail of geographical range and spiritual reach, opening the comforts of relationship in unfamiliar circumstances, in the American colonies as well as in Britain: ‘where-ever they came, [they] were acknowledg'd by their Bretheren, and received with all Chearfulness’.Footnote 25 Methodism absorbed its members’ particular environments and experiences. By the late eighteenth century, Welsh-language tickets created a distinctive bond; in Scotland, Methodists adopted an additional metal token as a ‘badge of church membership’.Footnote 26 The ticket underwrote identity in both a social and a spiritual sense, in individual and collective settings.Footnote 27 It was a marker of adulthood or independence, not given to young children.Footnote 28 While the device itself was a novel idea, it drew heavily on biblical formulations in separating god-fearing people from the unworthy,Footnote 29 and Wesley explicitly represented his tickets as direct descendants of the ‘Commendatory Letters’ mentioned by St Paul or ‘Tesserae’ (tokens, tallies, and, figuratively, signs and passwords) sanctioned by the Ancients.Footnote 30

Wesley claimed that showing tickets was ‘a thing … never heard of before’,Footnote 31 but exactly where the idea came from is unclear. Tokens had been used since the sixteenth century to monitor and regulate access to communion.Footnote 32 Those Bristol tickets followed shortly from Wesley's engagement with and then break from the Moravians who not only issued tokens allowing individuals to enter particular religious meetings but also conducted church business by drawing lots, another type of eighteenth-century ticket with ancient antecedents and contemporary resonance.Footnote 33 More relevant probably were mainstream tickets of admission, including those produced by numerous eighteenth-century voluntary organizations. These were endorsed with signatures and seals giving admittance to fund-raising church services, performances, and dinners.Footnote 34 On a similar principle, Anglican bishops had already used tickets to manage large-scale confirmations, although it was not until the Methodist ticket was well established that the practice was systematized and became widespread.Footnote 35 In the second half of the century, religious denominations introduced pew ‘tickets’ to fund their buildings. These became an important financial measure for Methodists too, although their dockets for such payments usually referred to pews, sittings, or seats, preserving a special place for their ticket.Footnote 36 From the outset, therefore, Methodist tickets were attuned to contemporary developments, particularly urban patterns of sociability and association.Footnote 37 But none of the contemporary parallels quite prepare the historian for the power of Wesley's particular deployment of the form.

Wesley recognized a potential in the ticket to compress and intensify social processes, especially around membership and order. His account of those first tickets explained that a name written there was equivalent to a recommendation ‘at length’: it underwrote credit and character.Footnote 38 Wesley invested a piece of paper with symbolic authority and incorporated it into a ritual of gaining entrance to meetings and of quarterly examination. Crucially, possession of a ticket gave religious commitment, enthusiasm, experience, and reassurance a solid form. Unlike the admission or lottery ticket, which had life or currency in relation to a single event,Footnote 39 Methodist tickets represented a pervasive force over daily life, a visible reminder of enduring struggles for spiritual improvement. Once issued, the Methodist ticket exerted its power through a material presence and keeping close to the possessor. Early examples were printed on ‘small, thick cards capable of going through the rough wear of a quarter’; many were folded by their owners and perhaps tucked into a pocket book or work of devotion.Footnote 40 It differed from other eighteenth-century tickets that released their primary benefits when let go at the door, for example. The Methodist ticket structured time spent and emotions felt. In restricting access to the love-feast, it heightened expectations and promised religious privacy.Footnote 41 As instruments of practical supervision and certificates of moral behaviour, tickets constituted the society or ‘Connexion’ and its subsequent arrangement into bands and classes with separate tickets for each, as well as a transitional ‘on trial’ version and an occasional ‘Note’ for entry to the love-feast.Footnote 42 In the process, it created a form of human equivalence through which every member, of whatever social status, equalled one ticket. Thomas Taylor, an early Methodist preacher in Cork, let no one, not even the class leader or steward, enter a meeting ‘without producing his ticket; and the work of the Lord prospered on every side … I insisted on poor and rich meeting in class, or not to have any privilege of meeting in society.’Footnote 43 The ticket is therefore the material sign of the new religious phenomenon that was Methodism, capturing distinctive features of the movement and of Wesley himself.Footnote 44

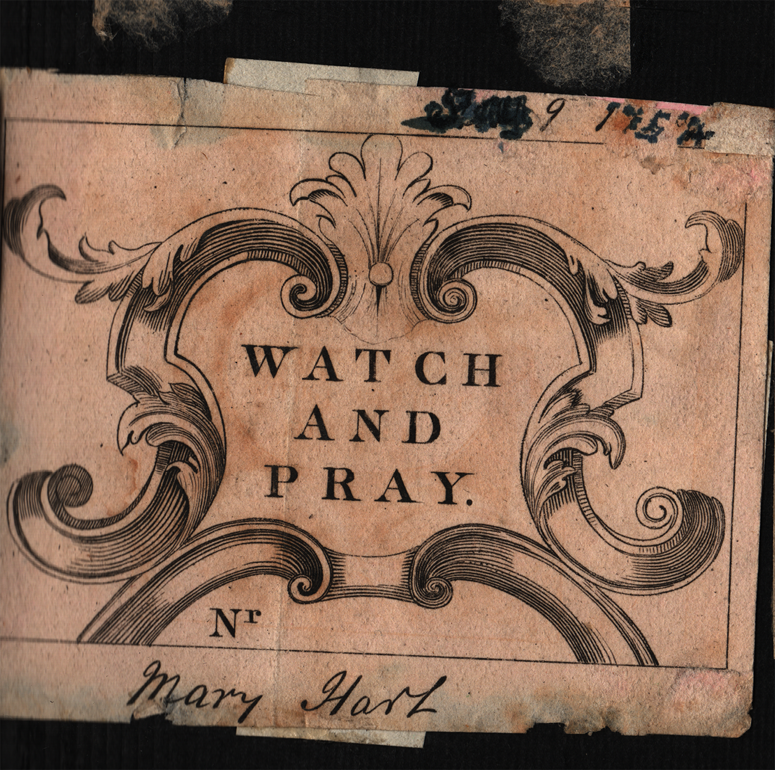

The Bristol tickets of 1741 were almost certainly handwritten slips. None survive. Ornamentation followed swiftly: leafy scrolls, vases, an angel with trumpets, sun, crown, and clouds, all probably taken from printers’ decorative stock. A few designs included general exhortations. For the first decade at least, Methodist tickets had no fixed style or size and were locally determined, with different practices of distinguishing the current quarter (such as by colour).Footnote 45 Emblems featured, some attracting hostile comment: ‘Popish pictures and devices upon them as of the Virgin Mary, a Crucifix, or Lamb’.Footnote 46 Two characteristics differentiated Methodist tickets from the devotional form of the Catholic holy card: a biblical quotation and an initial letter, which denoted the quarter and ran in regular sequence. These appeared in 1749/50 and 1760 respectively.Footnote 47 From the mid-1760s, they were set within a black decorative border and there were no more pictures, although the size and shape of the ticket continued to vary. ‘Watch and Pray’ of 1754 was one of the largest (8.5cm x 7cm) (Figure 1); a ticket cut from a printed sheet in the 1760s was approximately 3.5cm x 6cm. The new pattern of 1822 (8cm x 6cm) was considerably bigger than its immediate predecessor, hinting perhaps at changing practice and purposes.Footnote 48 Across the Atlantic, Americans shared the design of border and text, but by the early 1800s had reorientated their tickets, distinguishing the quarters in their own way.Footnote 49

Fig. 1. Kenworthy Class Ticket Album. From the collections of the Oxford Centre for Methodism and Church History, Oxford Brookes University, Oxford, UK. Used with permission.

Arranged in chronological order, therefore, surviving tickets record a mode of religious kinship; they chart the institutionalization of Methodism and its global realignments. Wesley's writing on a ticket – the recipient's name, a number or a date – transformed an inert, quotidian scrap into an active testimonial. It was also a kind of authorship. But as numbers grew, Wesley could no longer administer the system personally. Assistants now delivered tickets ‘where we cannot do it ourselves’.Footnote 50 Every three months, supporters across the country got the ‘Society Tickets ready’,Footnote 51 cutting them from large sheets and making annotations. Women participated in at least some circumstances.Footnote 52 Each member was questioned on spiritual progress before the preacher wrote the recipient's name on a ticket and then presented it ‘in a very solemn manner’.Footnote 53 Only in the nineteenth century, in Britain and America, did issuers regularly sign or initial the ticket.Footnote 54 From the mid-1760s, the British pattern was sent quarterly ‘from London directly’ marking a process of standardization, generating complexity and activity.Footnote 55 By 1807, class and band tickets were printed centrally at the Methodist Conference Office in London and sent ‘to every town and village in the United Kingdoms which contains a Methodist Society’.Footnote 56 An increasingly elaborate system of letters and dates required a bureaucracy of examiners to check for current marks to regulate access and membership. Tickets required a distinctive form of plebeian literacy, an adequate competency in reading both print and script, and specialized skill in interpreting the information they gave, including the large letters.Footnote 57

William Clowes's 1805 conversion narrative supplies the best contemporary account of Methodist door-keeping and ticket practice. After a rackety youth and several failed attempts at self-reformation, a neighbour invited him to a Methodist preaching. Clowes agreed to go because it was dark, so he would not be seen. But when they heard a love-feast announced at the end of the meeting, his companion offered to go home and leave Clowes with the ticket which he had borrowed from his mother-in-law ‘for the purpose of getting in’:

So, feeling inclined to see this meeting, and my curiosity being thus excited, I took the ticket, and with it directions how to act, in order to gain admission. The person told me, in showing the ticket to the door-keeper, I was to cover the name written upon it with my thumb, and just let him see the alphabetical letter, and thus I should be allowed to pass on into the chapel. Accordingly, we both went up to the chapel door, and my companion, observing that the door-keeper, instead of giving a rapid glance at the presented tickets, took them out of the hands of the individuals, and examined them minutely, said to me. ‘Come, we must go home; I see neither of us can get in.’ But, at the moment, I felt neither any disposition to return, nor to give my friend his ticket back; and, just as I stood in this undecided state, a puff of wind came, and blew the door-keeper's candle out. In a moment, I presented him my ticket; but on taking it into his hand, he called for another light, and just as he was going to read the ticket, another puff came, and away went the light a second time. The man being fluttered and disappointed, hastily pushed back the ticket into my hand, saying, ‘Here, here, move on.’Footnote 58

The ticket had material power; it was a vital agent in a divine drama.

Wesley made extensive use of the press, requiring his followers to become adept readers. Printers played a significant role in Bristol evangelical circles mid-century, and the Methodist ‘Book Room’ was another sign of the movement's confidence and power.Footnote 59 As scholars have noted, Methodist belief worked through text and oral tradition.Footnote 60 Controversy and anti-Methodist sentiments, against which adherents defined and tested themselves, were predominantly expressed in print: in this analysis, public debate shaped Methodist identity to the extent that Methodists’ understanding of their own religious emotions, and of the world in which they lived, was a discursive or rhetorical effect.Footnote 61 Tickets have not featured in this argument, but as printed items they appear to be implicated. They are associated too with another line of interpretation that develops parallels between early Methodism and theatricality, a point that eighteenth-century critics also relished.Footnote 62 But as long as tickets sit on the margin of historical interest, they pass unnoticed to appear only fleetingly in a scholarship focused elsewhere. Yet even these occasional references suggest that the Methodist ticket was a significant marker, albeit one operating differently to more familiar linguistic forms of religious expression. So a letter from 1785 that confirms the importance of print and literacy in framing Methodist identity contains within it a curious acknowledgement of the ticket as a transformative force: ‘I wished I had not got a ticket for I feared they would read me out of the society – who knew the misery I was in but those who have experienced the arrows of the Almighty.’Footnote 63

The problem is this. Wesley's introduction of tickets was one aspect of Methodism's deep engagement with eighteenth-century innovation, including print. But the ticket was a distinctive sort of print. In the sense that it displayed words, it was a text. However, it does not easily fit into scholarly analyses of Methodist discourse: its scant type does little to explain or convey those religious feelings which found more expansive expression in other literary genres. In addition, the tangible presence of the individual ticket could be significant: it did things, like opening the possessor to be ‘read’, giving it a form of life that the reproducible book or pamphlet did not. But unlike the solitary, unique personal letter, the ticket emerged from the press with thousands of identical impressions and was then made unique through the addition of a name by hand, a process that sometimes associated an ordinary worshipper with a notable individual.Footnote 64 The Methodist ticket was a hybrid, both print and script, text and object; at times, it transcended words and text altogether, as we shall see in the foundation of Primitive Methodism.

Recent studies of ephemera emphasize the special characteristics, ubiquity, and influence of cheap print. By looking at numbers produced, the speed with which they circulated, the value attached to them, the uses made, these scholars emphasize an item's ‘capacity’.Footnote 65 Originating in John Wesley's disciplinary authority, tickets became an effective administrative device to count, regulate, and tax an expanding membership: ‘Give no ticket to any that wear calashes, high-heads or enormous bonnets.’ The same applied to those who wore ruffles or consumed smuggled goods, or who failed to attend class meetings.Footnote 66 In 1802, the Irish conference withheld tickets from women who preached.Footnote 67 From the 1740s, the annual conference deliberated on ticketing matters. Regularly minuted decisions developed and refined rules around the practice of showing tickets:

Q.13 [1752]: Shall we permit any to be present at the public meeting of the bands who have not band-tickets?

A: Certainly not. By that means we should make them cheap, and discourage them who are admitted.

Q.14 [1752]: What if one forget his band or society ticket?

A: He may come in once; but not if he forget it two times together.

Q.30 [1781]: Let no stranger be admitted; and let them show their tickets before they come in … Has it been observed in the Birstall circuit?

A: Hardly at all. Let the preacher, stewards, and leaders see this observed for the time to come.Footnote 68

So central was the ticket to the movement that as financial arrangements fell into a regular groove, Wesley's followers used the term ‘ticket money’ to describe the shilling they contributed as a thank-offering every quarter when each new class or ‘Society’ ticket was issued. Although it was not always paid in full, it was a major source of income.Footnote 69 For a critic of Methodism, like the bookseller James Lackington, ‘money seemed to be the principal end of issuing tickets, at least in country places, the members in the community being so well known to each other, that they scarce ever shewed their tickets in order to gain admittance’.Footnote 70 Lackington downplayed the ticket's capacity, its promise of religious intimacy.Footnote 71 However, it projected individual singularity, as expressed in a name, while conveying an intense experience of community. It is a pattern similar to that Bruce Hindmarsh has noted in raw narratives of religious conversion.Footnote 72 An emotional and spiritual force field, which belied the ticket's unassuming appearance, emerges most clearly when tickets played an active role in disputes and in reconciliation following episodes of conflict.Footnote 73

When Wesley purged the Society and ‘many were put away’ in October 1743, the ticket was the sign. A woman stripped of her ticket was ‘a dead thing out of mind!’ to be abandoned by her friends.Footnote 74 The loss of credit and character were palpable. Division between John Wesley and Thomas Maxfield over theology and prophecy in 1763 was acted out before Wesley through the ticket:

Mrs C[oventry], cried out, ‘We will not be browbeaten any longer; we will throw off the mask.’ Accordingly a few days after, she came and, before an hundred persons brought me hers and her husband's tickets and said, ‘Sir, we will have no more to do with you.’Footnote 75

‘More and more persons threw up their tickets every day’ as the breach widened.Footnote 76 Far more dramatic than simply walking away, this gesture suggested what Wesley's critics also suspected, that these objects were at least partially understood as ‘Assurance and Salvation-Tickets’. Wesley denied this as a ‘mixture of Nonsense and Blasphemy’, just as he rejected Thomas Church's allegation that the Society was outside the Anglican Church because ‘you have delivered and given out Tickets to those, whom you thought proper to continue as Members’.Footnote 77 But for Maxfield's intimates, Wesley's tickets had become worthless and meaningless, something to be discarded along with Wesley himself.

Four decades later, tickets marked the ruptures that created Primitive Methodism. William Clowes and his contemporary Hugh Bourne (converted to Methodism in 1799) were inspired by the American camp meeting model to hold large, outdoor revival gatherings in the Staffordshire Moorlands, but these were uneasy political times, stirred by fears of revolution, war, and internal sedition. The national Methodist conference rejected the practice as unsuitable for Britain; local leaders, who had already cautioned Clowes against noisy religion, expelled Bourne in 1808 and Clowes in 1810 through the quarterly meeting and non-renewal of the ticket. Clowes, unlike Mrs. Coventry, recorded the experience: ‘I was told that I was no longer with them; that the matter was settled.’Footnote 78 Both men continued their activities, building networks of supporters, and in May 1811, Hugh Bourne ‘ordered tickets to be printed for the first time’.Footnote 79 Tickets marked the amalgamation of separate groups into one Connexion, constituted their physical separation from the Wesleyan Methodists who had rejected them, reconfigured their relationships, and marked a new ‘corporate life’.Footnote 80 A pithy biblical text reinforced the message: ‘as concerning this sect, we know that every where it is spoken against’.Footnote 81 Subsequent historians took that first ticket as the denomination's ‘certificate of birth’; when the branches reunited in 1932, the ‘last’ ticket summed up the occasion.Footnote 82 Tickets are an essential component of the Primitive Methodists’ origin story, but it is striking that in a biblically saturated culture in which ‘the beginning was the word’, they only named themselves in February 1812: the ticket came before the name, before denominational rules, in marking the break.

Bourne issued those first tickets because his followers wanted them, an expectation established through early Methodism. Although many apparently thought that this would be a one-off event, the series of Primitive Methodist tickets demonstrates the extent to which religious habits could not now be imagined without them. The question initially arose in response to financial need with subsequent discussion focused on the costs of printing. But economic motives were again only part of the story, because Bourne tied this moment into his broader theology: ‘It may seem strange … that quarterly tickets were not sooner introduced’, he noted in his journal, but the explanation was clear. The Connexion had begun ‘in the order of divine providence’ when godly zeal held it together; but that state did not last. It was the ‘wisdom of man’ not the ‘wisdom of God’ that required ‘some visible bond’ between members. In short, the ticket was an ‘inestimable blessing’, a bracing antidote to human weakness, timidity, and inactivity.Footnote 83 Issued and renewed by the preacher, the Primitives’ ticket served as a financial and supervisory instrument, but it revealed the workings of salvation.Footnote 84

Wesley's intellectual genealogy of the ticket had claimed the authority of the apostles and ancient Romans; his followers brought meanings grounded in their own experience.Footnote 85 For all the power of print and literacy, a Methodist folk tradition asserts that members were buried with their tickets. Whether or not this was the case, it is a story about the reach of paper beyond earthly life, a practice beyond Latin or theology, but imbued with subjectivity and value.Footnote 86 Precautions taken against forgery and impersonation reinforced the ticket's latent power.Footnote 87 Joanna Southcott, the millennial prophet, passed through Methodism in the 1780s before issuing her own ‘seals’ or protective guarantee of salvation.Footnote 88 She was no stranger either to the symbolic power of paper in her disputes with Anglican clergy: ‘Then you sent to me to give in my sacrament ticket, to turn me from the altar … I returned to you every demand you had of me, by returning the sacrament tickets.’Footnote 89

When Mrs Coventry rejected Wesley, she not only returned her own and her husband's tickets; she flung back her daughters’ and her servants’ tickets too.Footnote 90 It was a moment that caught the gender and household relationships of eighteenth-century Methodism, where women were numerous, active, and visible participants.Footnote 91 When pressed, one husband answered that his wife was ‘at her own liberty’ to attend meetings.Footnote 92 Women held tickets in their own names: the overwhelming majority were written without any preliminary title; upon marriage only their last name changed. Many would have been familiar with other types of ticket, including two that were important in female plebeian circles: the seaman's pay ticket, which was the centre of financial transactions from the mid-seventeenth century, and the pawnbroker's ticket, introduced in 1757. But Methodism gave specific, quasi-familial characteristics to the social interactions and flow characteristic of the eighteenth-century ticket.Footnote 93 These elements were not fixed in 1741, but developed through use. As the appearance of Wesley's early tickets changed, so pictorial, tactile, and textual literacy accumulated; the balance of skills shifted too with the move towards text. Knowledge of what tickets did and their role in a distinctive religious experience was not solely for Wesley and his itinerant preachers to decide; these matters were settled through long and collective participation. Women were therefore significant in shaping a familiar object that here acquired disciplinary functions. If we need a reminder of the complex boundaries between public and private affairs in the early modern period, Mrs Coventry had an instinctive feel for the possibilities in such interconnections. For women, as well as for men, these scraps of paper were an intimate possession but also political, in the sense that they concerned power within and beyond the household.Footnote 94

As Methodism spread globally, the ticket circulated in other unequal societies, where it created a paper network that intersected with human relationships and bonds. By 1815, over 40,000 black Methodists in the United States and a further 15,000 in the Caribbean islands carried a ticket.Footnote 95 But what did it do for the enslaved woman or man who was denied legal personhood and property rights; how did slavery modify the mobility and meaning implicit in tickets? The evidence is difficult, with some missionaries stressing disciplinary use and conformist effects: ‘I have been obliged to deny tickets to many, on account of their lukewarmness and neglect of the means of grace.’Footnote 96 However patronizing the missionaries, their minds suffused with racial thinking, a hint of equivalence lurked in contemporary ticket practice. In 1799, some of these ticket-holding enslaved Methodists on the Virgin Islands joined a revolt. In response, the planters bent ticketing to their will in demanding that ‘none in future should be admitted into the society, unless they had previously obtained a ticket from their respective owners, signifying their approbation’.Footnote 97 In early nineteenth-century Antigua, the Hart sisters, who created a specific black Methodist identity, saw the ticket as a marker of both beginning and belonging.Footnote 98 Racial discrimination determined some African Americans to organize separately from white worshippers and issue their own tickets.Footnote 99 In negotiating a relationship, the ticket would always be political, but personal meanings could undercut or sharpen formal rules.Footnote 100

Meanings change over time. The introduction of the Methodist ticket was a product of religious fervour and eighteenth-century cultural innovations. As Methodism settled, as the tools of association became increasingly familiar, the ticket slipped into accustomed roles. These were not insignificant, since break-away sections asserted independence and faithfulness to Wesley himself by issuing their own tickets (not only the Primitives in 1811, but the New Connexion in 1797; Bible Christians c. 1823; New York's Stellwellite group in 1821).Footnote 101 The Primitives’ first tickets were very similar in appearance to the contemporary Wesleyan model: until 1829, when the Primitives added their name to the paper, up-to-date knowledge of the biblical text and initial letters currently in use was required to distinguish between Connexions. Printing continued to play a significant role, as it had in Wesley's day.Footnote 102 The Methodist ticket was from its first issue, whether by Wesley or Bourne, a marker of presence and endurance. Later historians and leaders of Methodism foregrounded its administrative value, adapting it to contemporary concerns and priorities. But the dynamics of remembering that made the Methodist ticket an aid to institution-building had other consequences too. The new Primitive Methodism ticket design of 1829, including the provocative words ‘First class formed in March, 1810’, exacerbated a dispute between the movement's founders by asserting precedence for one branch linked to Hugh Bourne.Footnote 103 Another effect of history-making was to eliminate some capacities of the ticket altogether: the puff of wind that extinguished the candle in 1805 and brought Clowes to religion was omitted from subsequent accounts, rendering the ticket incidental and mundane.Footnote 104

Overall, the Methodist ticket increasingly became a ‘ticket of membership’, a phrase the Wesleyans printed on theirs from 1893.Footnote 105 Here, it followed a general social trend in which the multiple meanings of early modern tickets consolidated into a narrower range.Footnote 106 As the Methodist network of chapels expanded, church income depended more on seat rents and congregational collections than on the quarterly ticket.Footnote 107 By the early nineteenth century, some had redeployed it as a begging certificate; one late century commentator complained that relaxation of ticket discipline had gone so far as to diminish spiritual life, although an unfortunate choice of text could still cause a stir.Footnote 108 Evidence of the ticket's continuing relevance is not necessarily found in church documents or authoritative pronouncements, however. It lies instead in practices of saving and collecting. The Encyclopaedia of ephemera missed Methodism altogether and declared the ticket ‘among the most ephemeral of printed matter … rarely preserved deliberately’.Footnote 109 But as numerous surviving Methodist tickets demonstrate, that judgement is misleading. Unusually for ephemera, it is also possible to know something about recipients of the Methodist ticket, these ‘consumers’ of print.

II

What can be said of those Methodist tickets that still exist? The inky trace of a Wesley ensured that some circulated through families, between collectors and archives, long after their immediate use had expired.Footnote 110 More women's tickets survive from eighteenth-century Methodism than men's, roughly on a ratio of two to one, a figure broadly in line with the demography of the movement.Footnote 111 Underlying this pattern are groups of tickets each associated with a single name: over ninety belonging to Margaret Sommerhill of Bristol, including four from 1742, which are the earliest known from Wesley's experiment. She died at a great age during the 1790s, leaving a lifetime of tickets wrapped in her Methodist class paper.Footnote 112 Clearly, Sommerhill's memory and personal history were bound up with the materiality of her tickets, many of which are now rubbed, faded, and torn (Figure 2).Footnote 113 A succession of tickets located individuals within a stream of time, enabling them to orientate themselves within the movement and within god's providence, to see the shape of their lives, to give meaning to time past.Footnote 114 It constituted a type of life history, but was also vulnerable to loss and decay.Footnote 115 In the first instance, therefore, some worshippers put their own tickets on one side at the end of a quarter, perhaps adding them to a small bundle of expired items; it was a habit distinct from (subsequently) collecting them. When tickets outlived their original possessor, it becomes more difficult to establish who kept them and why.

Fig. 2. Four tickets belonging to Margaret Sommerhill, 1742; a fifth has clearly been removed at a later date (JRL, MA1977/720: James Everett Album). Reproduced and published with the permission of the Trustees for Methodist Church Purposes and John Rylands Library, University of Manchester.

Cultural critics usually distinguish between habits of saving or ‘accumulating’, which they locate in everyday life, and the practice of collecting, which they associate with system and pattern. Collecting is the process of ‘gathering together and setting aside selected objects’.Footnote 116 During the eighteenth century, it can be found in well-established customs of news gathering, and a popular antiquarianism around the theatre: both fashioned a type of social history and participated in a lengthy shift from oral to scribal memory.Footnote 117 Collecting expresses desire and subjectivity through creating a series out of singular items; it offers an illusion of return to a particular moment in the sequence.Footnote 118 In playing with time, in recuperating the past, it harbours nostalgic associations.Footnote 119 We have already seen how the Methodist ticket embodied a sense of self: the process of collecting it was to add new layers of subjectivity and memory. Interest began early. The preacher Samuel Tooth (fl. 1770–1820) acquired tickets from the 1750s and 1760s, including one in John Wesley's hand.Footnote 120 Each item was tied to a specific quarter in the year, but gestured to a redemptive state beyond death, beyond time.

The concept of ‘collecting’ is not a neutral one. Defined through the behaviour of a subset of collectors, class and gender assumptions abound: elevating rational system above personal accumulation; prioritizing elements of public display above domestic, ‘private’ concerns; valuing a separation from, not an integration with, the everyday.Footnote 121 Scholarship on eighteenth-century collecting orientates itself around a concept of connoisseurship. Where women are its subject, they are predominantly elite and deeply embedded in fashionable sociability.Footnote 122 But prepositions matter: there are collections of popular material and collecting by non-elite women and men.Footnote 123 Methodist tickets are a perspective on collecting by ordinary people out of the substance of their own lives, and as such are unusual: tickets survived because their meaning and power were never exhausted, because they served new purposes across generations. Methodist collecting had its own imperatives: neither a cabinet of curiosities, nor rigorously taxonomic; not fashionable, but probably sociable; not scientific, experimental, or philosophical.Footnote 124 It shared with other collecting practices a capacity to fix knowledge about the world; it established relationships and got close to people. It materialized patterns of family and spiritual belonging.Footnote 125 Characteristics of the eighteenth-century Methodist ticket therefore challenge models of collecting as a form of consumption and commodification.Footnote 126 Did the ticket lose its religious and social capacities once collected? Did collecting the ticket change its value? In short, how does a history of collecting intersect with the ticket's shifting meanings, and the personal and professional identities of those who collected it?

Tickets survived because there were places to keep them. Decades after they were first saved, tickets were collected and later glued into blank notebooks, printed pocketbooks,Footnote 127 cheap devotional texts, and albums, leaving a distinctive pattern of memorialization, akin to collective biography. By the early nineteenth century, individual Methodists were anthologizing the movement. Their labours continued a long tradition of non-elite record-keeping which registered the passage of time, and events of personal and communal significance.Footnote 128 Over the course of the century, such activity resembled another form of popular literacy, a fashion for scrap-books, which also dealt in pattern and meaning, and were frequently shared by the women and men who crafted them.Footnote 129 It is not always clear who assembled an album, but when its contents reflect a family network, the creator probably had some personal connection with the material. Margaret Hutchison used a handsomely bound edition of Italian poems to create her ‘Society Ticket book’ in the 1830s.Footnote 130 The first ticket is Robert Hutchison's from December 1804, with Margaret's earliest dated December 1819. Her choice of an engraving of Sarah Wesley, Charles Wesley's widow, to obscure the original frontispiece may have been determined by available materials or express a more subjective, matrilineal history. What is striking about many Methodist collections is that they are full of personal and collective, if elusive, meaning.

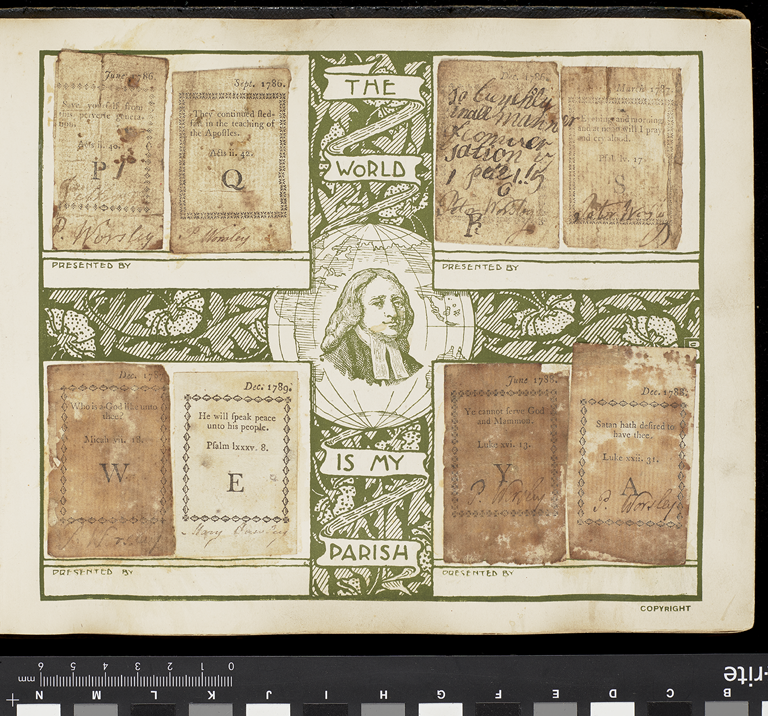

As anthropologists and psychologists observe, people remember (and forget) through things; things evoke thoughts and feelings.Footnote 131 Collective identities can be constructed through material remains; possession creates an experience of belonging that shadows the past and hovers around others’ lives. By the nineteenth century, tickets bridged generations; they offered a physical link with those who once held or folded them.Footnote 132 In some instances, they became a courting record; in most, they constructed a genealogy through Methodism: ‘two class tickets of my great grandmothers [sic] before her marriage’; ‘Mother's sister she died soon after.’Footnote 133 A sequence of tickets reinforced the early significance of personal story in Methodist expression of spiritual experience.Footnote 134 It resembled collaborative practices of life-writing, through which Methodist women created spiritual friendships and memories, establishing a place for themselves in history.Footnote 135 Tickets migrated with families and collectors, a process of global relocation that extended Methodism's paper network and complicated its geographical foundations.Footnote 136 Tickets were handed on: in 1891, H. M. Booth left their grandfathers’ and parents’ tickets to a sister or brother.Footnote 137 Archives reveal people who cannot quite throw tickets out, who post them off in the hope of finding a safe repository, of converting a process of saving and collecting into archiving, preserving, and memorializing.Footnote 138 It is as if tickets embodied the dead and their trust in the living: ‘My Uncle's loving collection of Class Tickets … I hope I am doing the right thing.’Footnote 139 By the early twentieth century, there was sufficient interest for an astute publisher to recognize a commercial opportunity, a variant on the cigarette card collection. George Thompson of Paternoster Row marketed a decorated John Wesley Class Ticket Album with John Wesley's signature in the title and his motto, ‘The World is my Parish’, incorporated into the coloured page designs. Intended to display four tickets of the current shape, owners stuck in older ones, which were smaller or irregularly sized, putting albums and tickets to their own purposes (Figure 3).Footnote 140 In the twenty-first century, tickets can still stand for people: ‘We were sorry to hear about the death of Miss Edith Hargreaves … The above Photocopy of class tickets formed part of a collection handed down from her father. We print them as a token reminder of Edith and her devotion to Methodism and its traditions.’Footnote 141

Fig. 3. Page from the John Wesley Class Ticket Album (JRL, MA 1981/12). Reproduced and published with the permission of the Trustees for Methodist Church Purposes and John Rylands Library, University of Manchester.

An urge to collect beyond immediate personal association accelerated in the second half of the nineteenth century. Where it is possible to identify them, men predominated as comprehensive, systematic collectors; some were professionally committed to the movement which gave them privileged access to materials. They aimed for whole sets, but in valuing the earliest tickets, produced large collections not necessarily representative of the genre as a whole.Footnote 142 As for the difference in collecting styles, we need make no judgement on their relative value.Footnote 143 James Everett (expelled from the Wesleyan Connexion in 1849 and subsequent founder of the United Methodist Free Church) was the acknowledged authority. He acquired Margaret Sommerhill's from the preacher and scholar Adam Clarke (c. 1760–1832), who had first secured ‘the whole of the good old woman's tickets’. Everett sold his extensive two-volume collection to Luke Tyerman, biographer of John Wesley, and Tyerman's son presented it to the Methodist conference for safe custody in 1894.Footnote 144 Everett had to make do with a sketch of Ottiwell Higginbotham's 1752 ticket, however, as Higginbotham's daughter, who asserted that familial collecting tradition, refused to part with it.Footnote 145 He arranged his tickets chronologically, adding handwritten ‘Remarks’ and ‘Events’ to create a history of Methodism. The year he chose to divide the volumes – 1839, the centenary of Methodism – demonstrated a conscious attempt to chart the movement. But Everett had another purpose in mind too: he recommended reading entries regularly through the year to preserve ‘a lively recollection of the History, and dealings of God with the body’.Footnote 146 For men as well as for women, therefore, tickets conveyed a type of family chronicle. Collectors also provided illustrations for works of Methodist history. In the tradition of scrap-booking, a number of early twentieth-century albums hold facsimile tickets, including those of Margaret Sommerhill, cut from published plates and pasted into the sequence to give an impression of origin and completeness.Footnote 147 James Edward Kenworthy of York carefully distinguished his photographic copies from ‘real’ items.Footnote 148 These acts of reproduction, so very different from the initial purpose of the ticket in guaranteeing a worshipper's identity, again change the ticket's meaning and purpose. In a period of standardized tickets, this practice placed value on what was unique or particular about the earliest examples, but it did so through means that multiplied and replicated those very qualities, so that Sommerhill's ticket was no longer unique but existed in many places at once.

In some instances, an immediate link to original items was lost but they found a new place within institutional memory. In 1937, the East Anglian District received some old Wesleyan class tickets belonging to the Hinchcliffe family of Denby Dale. Tickets dating back to 1827 had been stuck into a lined exercise book with an assortment of loose items added, such as a card of ‘old class tickets lent by Miss E Greaves of Tadcaster’. ‘It is of course of no value to me’ wrote W. Heap to the Central Office, but the reply assured him that it would be of use to the Methodist Museum and Heap duly sent the items to London.Footnote 149 On the death of Richard Broad, a Congleton dentist, in 1899, the Museum received his brown notebook on loan. While the names written on some of the tickets suggest that the collection originated in Broad's own family, the cover simply recorded ‘Old Methodist Class Tickets. Valuable.’Footnote 150 From the very beginning, ideas about use and value ensured the survival of an individual ticket. Harking back to the original Methodist Connexion, tickets expressed personal and group identities, all bound up in an elusive trace of memory. But to the extent that these imperatives were shaped by broader cultural currents, they were mutable signs.

Among family memorialists and historians of the movement, acquisitive enthusiasts left their trace in albums stripped of tickets.Footnote 151 Kenworthy signed off his ambition to have one or more examples a year from 1750 to 1949 as follows: ‘on my 79th Birthday … this Collection was completed’. J. H. Verney borrowed it in the hope of locating some of the thirty-five tickets missing from his updated catalogue of tickets. After Kenworthy died in 1954, Verney described their relationship as of ‘friendly rivals’ who both advertised for new additions.Footnote 152 Collecting can generate psychological satisfaction and a sense of communityFootnote 153 but even then, the choice of Methodist subject lends a distinctive character, with access to co-religionists, family, and friends giving an advantage in the dedicated pursuit of rare examples. While it is possible to distinguish Margaret Sommerhill's quarterly habits from Verney's meticulous cataloguing, and perhaps read into the difference a broader shift from household religion to institutional church, this is an over-simplified conclusion. Similarly, gender distinctions do not fully account for practices that crafted either a family story or a formal chronicle from old tickets. Collecting is bound up with the construction and fixing of memory. As a response to human transience, it expressed a need to give life meaning, individually and collectively.Footnote 154 By the nineteenth century, the ticket was a church record, but its fragile link with past generations also made it into a profoundly nostalgic object in suggesting a recovery of what had irrevocably gone. The object itself was material ‘proof of unbroken association with the people of God’.Footnote 155 For one York chronicler, writing of people ‘long since pass'd away’, only a ticket ‘in my Poss[ess]ion’ connected the name of Cooper with Methodism.Footnote 156

III

When James Lackington recorded his youthful adventures in Methodism, he still remembered, over twenty-five years later, the biblical quotations printed on his tickets.Footnote 157 He claimed a prodigious memory, but the feat alerts us to a broader mnemonic practice which, in Lackington's case, runs counter to his own avowal of the item's unimportance. Or perhaps even now he had his tickets to hand? Memories in tangible and intangible form cluster around single items and collections. Tickets carried more than words. They reached back into the past and recalled those now forgotten; they held on a thread what might seem to be of little moment.

Largely forgotten today, the ticket sits obliquely to all historiographies.Footnote 158 So what did it do? It was instrumental in Methodism's development: from John Wesley's first disciplining of the Bristol followers and establishment of the ‘class’, to conversion experiences and episodes of conflict and division. Its psychological and corporate power was such that in 1807, the ticket and quarterly visitations accompanying its distribution were described ‘as among the wisest and most politic institutions in the Methodist economy’.Footnote 159 Tickets raised revenue but their full capacities cannot be contained within a financial frame of reference. Tickets denied access in a moment, even to John Wesley.Footnote 160 They showed Margaret Sommerhill the enduring promise of god in the world. In a profound way, the ticket was the Connexion: it formed a Methodist; it created and expressed a new community. Generic attributes of the eighteenth-century ticket were crucial. Its ability to circulate, to give access, and to manifest transactions and relationships accommodated the lives of Wesley's early followers, who were often mobile, marginal, and seeking refuge from economic uncertainty.Footnote 161 It was this potential that Wesley seized and amplified. Through the ticket, individual souls shared an identity attuned to theological, spiritual, and social moods. It was a distinctly Methodist experiment, albeit one with broader implications. From the outset, the system facilitated patterns of female religiosity, with tickets issued to women in their own names, and women, their friends, and relations collecting them as a distinctive aide memoire. Tickets played a quotidian role in Methodist life and in the administrative elaboration of the church; a silent presence in many accounts, they enabled the pleasures of the love-feast and the confidences of the band meeting.Footnote 162 Tickets were a medium of expression and self-improvement, and instruments of salvation, subjectivity, and self. They could embody people. Far from incidental, therefore, tickets actively shaped Methodism and in the process they exposed new populations to the power of circulating paper, setting expectations of what it might do.

Methodist tickets are historically significant in a second sense too. They reveal aspects of the movement, including female presence and participation beyond preaching and missionary activity. They map Methodism's global dimensions, raising specific questions about the experience of enslaved Methodists, for whom ticket-holding was conditioned by captivity. The scale of Wesley's innovation emerges through understanding the larger contexts in which tickets proliferated in eighteenth-century Britain and attempts to create certainty around knowledge, identity, possession, and belonging. At a micro level, tickets passed through multiple hands, some of which left a mark in ink, stain, or crease. Methodist uses point to the sensibilities and activities of ordinary people, to household relationships and to improvised and at times idiosyncratic forms of history-making and (auto)biography. As material remnants, they illuminate religious practice and the role of memory in belief. Visual elements, print, and script on the paper's surface, manifested immediate bonds between worshipper, god, and community, and later conveyed denominational history.Footnote 163 Institutional contexts came to overlay otherworldly associations, although traces of the latter persisted. Were tickets slipped into coffins, asserting a faith in eternity in the face of loss and oblivion?

To appreciate the ticket's role in Methodism, whether as an active force or as a marker of trends, requires us to notice how contemporaries referred to, used, and understood it. Acts of collecting which create ephemera and preserve what was once dispensable do more. They are a third dimension, exposing characteristics of the objects themselves. Folded paper suggests how Methodists held, used, and saved their tickets; variant borders and irregular edges open production and preparation to view. Annotations on tickets and in albums reveal the workings of memory, but in the first instance survival required a place as well as a desire to keep things. Uneven patterns of survival and memorialization reflect material inequalities; tickets held by black and indigenous Methodists are rarely found in the archive, although unused blanks are there.Footnote 164 Possession, habits of saving and collecting, elements of routine and ritual, indicate how people ordered their worlds. As an object initially held close to the person, the Methodist ticket subsequently became spatially distant and separate, whether it was discarded or put somewhere safe. Over time, surviving tickets assumed new meanings and shed others. Valid for only three months, a succession of tickets constituted a distinct temporal rhythm that was the pulse of religious life. Collecting put them into a new, potentially open-ended timeframe. Nostalgia was one outcome of that later phase, an interaction of human and object that strained or longed to recapture the lifespan that was lost. The ticket sometimes reminded people of a fundamental, unbridgeable temporal gulf. Collecting is therefore integral to the Methodist story from 1741. While denominational and personal memories were significant for collectors, the objects in their collections had their own timescales, mingling spiritual and human life courses. Tickets intervened in history as a tactile form of genealogy, a way of belonging across time and generations; they become a vehicle for re-telling the past in terms institutional and personal, domestic and global, material, and sentimental.

Once visible beyond Methodism itself, Wesley's ticket suggests a fourth set of conclusions. It joins the range of cheap printing that extended far beyond books and prestige engravings.Footnote 165 Situated within broader narratives of social and economic change, of eighteenth-century urban growth and sociability, the Methodist ticket highlights reputation and identity. By underwriting religious standing, it created character and credit. As a pragmatic mechanism for moral endorsement, it responded to the needs of Wesley's early followers.Footnote 166 Plebeian literacy, which this object encouraged, here took some specialized forms. Access to and possession of paper and print were not necessarily commercially acquisitive decisions. Methodist tickets constituted a form of spiritual publicity stretching beyond town, coffee house, and debating arena. As others have already argued, eighteenth-century innovation was not necessarily secular, individualist, ‘modern’, or liberal.Footnote 167 After all, this ticket could serve a providential end; it was an expression of communal life.

A model of collecting based on connoisseurship tends to obscure original uses and misdirect attention away from those collecting practices which preserved religious meanings. Early collectors were distinctly ordinary; they emphasized the diachronic and serial, if only by virtue of saving tickets from successive quarters. Over time, tickets had multiple ‘owners’ or custodians, driving us to look beyond a framework of consumerism.Footnote 168 Across centuries, women and men participated in acts of remembering and forgetting, developing ideas about uniqueness and replication. Contrary to the standard definition of printed ephemera, the ticket was neither transitory nor minor; it was not simply a document.Footnote 169 If ‘ephemera’, literally, is a category situated in the day/everyday, the Methodist ticket is both within calendrical, mundane time and outside it altogether.Footnote 170

The questions that drove this study came from different fields, but no single method or theoretical insight wholly sufficed in reaching these conclusions. They require us to take the ticket seriously in its own right, as an object that people touched, held, studied, and also lost, forgot, and destroyed. For this reason, its capacity or agency matters; put another way, we need to focus on what was possible only because the ticket had a material existence and presence. The ticket, not a narrative about historical change or modernity, is centre stage. But as the literature on collecting indirectly reminds us when it focuses on present-day examples, or deploys psychological and psychoanalytic insight, tickets occurred within historically specific and mutable settings. Twenty-first-century comparisons are not always helpful. So in probing the ticket's capacities, temporal contexts are significant.

The ticket has been hidden in plain sight, both as an idea about how to do things and as a historical phenomenon. This article aims to restore it to Methodism and to the eighteenth century, and in the process to add new knowledge and perspective about the object itself and what it did. If there were no Methodist tickets, we would lose a form of plebeian literacy and organizational life; we would miss changing religious experiences and their incremental absorption, first into denominational expectations and then into nostalgia; we would forgo the challenges which complicate models of a bourgeois public sphere and a commercially acquisitive culture. This approach is one that searches for human existence in small things not major upheavals, and over long periods of time.Footnote 171 Patterns of cause and effect, so integral to the discipline of history, are often difficult to identify on this scale. But as the Methodist ticket demonstrates, apparent trifles can be powerful agents themselves.