Prosthetic joint infection (PJI) following total joint arthroplasty (TJA) remains a devastating complication after an otherwise predictable and well-tolerated procedure with significant implications on personal health and socioeconomic cost. Treatment of these infections are costly to both patient and system, requiring tremendous resource mobilization to provide the necessary multidisciplinary approach.

Outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT) has become a mainstay of treatment for the postoperative management of PJI following total hip arthroplasty (THA) or total knee arthroplasty (TKA). In addition to surgical management, Osmon et al Reference Osmon, Berbari and Berendt1 recommend that postoperative therapy should include initial intravenous antibiotics for up to 6 weeks followed by varying duration of oral suppression. In most cases, OPAT is delivered to PJI patients by way of peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs), which are managed by both the patient and delegates from home healthcare services. This delivery system allows a safe and effective means of antibiotic delivery while minimizing the time spent in healthcare facilities and resources utilized. PICC lines, however, are not without unique complication profiles that often prompt emergency department (ED) visits, unplanned readmissions, and frequent clinic visits, and that occasionally require premature removal of catheters and incomplete therapy. These complications have the potential to further increase costs of PJI encounters and place even more burden on an already strained healthcare system.

Very little information is available on rates of readmissions, unplanned ED visits, and complication profiles of patients who are undergoing OPAT after PJI. This information would be useful for providing patient-specific preemptive guidance on the relative incidence of potential postoperative complications. Thus, the purpose of this study was to characterize and categorize PICC complications in patients with PJI at our institution. The goal was to identify potentially modifiable patient factors and complications in a large cohort of PJI patients with the hope of findings areas of prevention and cost containment. We sought to answer the following questions: When do patients present to the ED with complaints related to their PICC and how long are their PICC lines maintained? What specific PICC complications are most common within the PJI cohort?

Methods

After receiving institutional review board approval, an institutional electronic health record (EHR) database was retrospectively queried from January of 2015 through December of 2020 for patients that developed a PJI after THA or TKA and required PICC placement as part of their multidisciplinary treatment. Overall, 889 patients were included in the study. The group’s previous index operations included 435 THAs and 454 TKAs that went on to be revised for PJI and required PICC placement (Table 1). In this study, infection was defined by the presence of a PJI diagnosis code alongside a revision procedure current procedural terminology (CPT) code. Codes were utilized according to the CDC NHSN recommended diagnosis and procedure codes for THA and TKA. Inclusion criteria included those who received a PICC line for administration of parenteral antibiotic therapy within 21 days of their secondary procedure, and only patients with PJI in the setting of THAs and TKAs. PJI secondary to all other instrumentation and prostheses were excluded. Additionally, PJI patients treated with isolated enteral antibiotics were excluded from this study.

Table 1. Demographics and Univariate Regression

Note. IQR, interquartile range; ED, emergency department; PICC, peripherally inserted central catheter.

Patients who received a PICC line at our institution are automatically enrolled in a robust OPAT management program to optimize outcomes. PICC lines are placed by a dedicated vascular access team (VAT) and antibiotic regimen is determined by a fellowship-trained musculoskeletal infectious disease attending in concert with a pharmacist and fellowship-trained orthopaedic surgeon. Dedicated OPAT pharmacists monitor weekly (or more frequently, if needed) outpatient labs and field questions from patients regarding medications and basic PICC line maintenance. Urgent orthopaedic questions are transferred to a 24/7 resident-run urgent care hotline. Patients are also able to directly communicate with their care team via the electronic health record messaging system. Finally, outpatient follow-up is performed at an infectious disease–orthopaedic surgery combined clinic, which is staffed with a dedicated PICC team to manage basic needs such as dressing changes and answering infusion questions.

Demographics, including age, sex, comorbidities, Elixhauser comorbidity score, and substance use (smoking and alcohol abuse) were collected. Additionally, with the discharge date of the PICC insertion encounter as the index, 90-day readmission and 90-day ED visits were reviewed. Although the standard OPAT treatment duration was 4–6 weeks, some patients encountered delays in PICC line placement or removal or required extended treatment. Therefore, a 90-day window was chosen to include the full duration of PICC lines and capture all relevant PICC-related ED visits. Additionally, as healthcare transitions to value-based care models, the 90-day window represents the global period for bundled payments and is critical in identifying outcomes that influence healthcare system reimbursement. Readmissions and ED visits were categorized based on primary diagnosis for ED or readmission utilizing the following categories: musculoskeletal or MSK (ie, superficial surgical site or musculoskeletal concerns), infection (ie, bacteremia, sepsis, or other nonoperative wound postoperative infection), PICC (ie, PICC-line–related issues, including malposition, occlusion, infection, thrombosis, removal, cellulitis, and hematoma), cardiopulmonary (ie, cardiopulmonary related issues, including any cardiac complication or any pulmonary dysfunction [including embolic events]), gastrointestinal or genitourinary or GI/GU (ie, chief complaints related to gastrointestinal or genitourinary problems), neurological (ie, any neurological or psychiatric complaint), and other (ie, constitutional, medication-related, pain, or dermatological). If a patient had multiple chief complaints upon presentation to the ED or readmission, only the final primary diagnosis from the billing record was included. Secondary diagnosis codes were reviewed to confirm that sequela of secondary diagnoses were not confounding primary diagnosis codes. Detailed manual chart review was further performed to categorize PICC ED reasons into malposition or readjustment, occlusion, infection, thrombosis, removal, cellulitis, and hematoma.

Descriptive statistics were completed on the entire cohort, the THA cohort, and the TKA cohort after patients were stratified into 3 groups: patients with no ED visit, patients with a non-PICC ED visit, and patients with a PICC ED visit. Age, as a continuous variable, is presented as mean (standard deviation) and analyzed with regression. Categorical variables (sex, race, comorbidities, substance use, Elixhauser comorbidity score, ED visits, readmissions) are presented as counts with percentages. We used χ Reference Li, Rombach and Zambellas2 analysis for categorical variables. For post hoc pairwise testing, P values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni method.

A multivariable regression controlling for age, sex, race, illicit drug use, and Elixhauser comorbidity score was completed to assess 90-day ED visits that were PICC-related (versus non–PICC-related and patients with no ED visits) and is presented as odds ratios (95% confidence intervals). Variable selection for multivariable logistic regression was performed by including variables that were significant in the univariate analysis to control for differences that may influence odds ratios in the multivariable model. A predetermined P value < .05 denotes statistical significance and both JMP Pro (Cary, NC) and R Studio (Boston, MA) were used for statistical analysis.

Results

Reasons for presentation and types of PICC complication

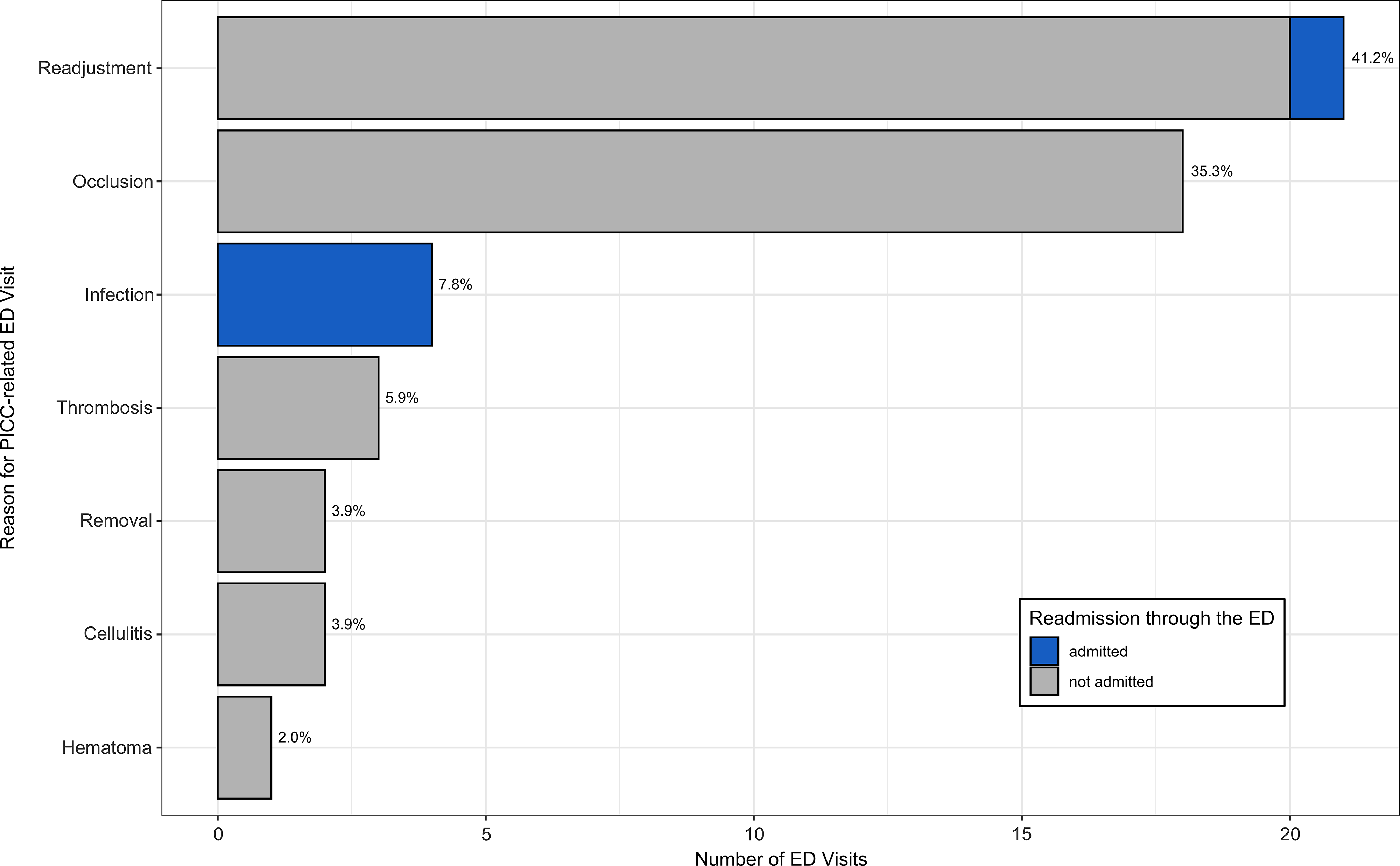

Demographic data are available in Table 1. The patients were 48.3% female and had a mean age of 64.6 years (range, 18.7–95.2). The cohort had 275 90-day ED visits (30.9%) and 51 (18.5%) were PICC related (Table 1). The median time from discharge to any ED visit was 20.2 days (range, 7.8–40.3) and the median time from discharge to PICC ED visit was 16.4 days (range, 10.8–30.4). Of the 275 overall ED visits, the primary chief complaints in decreasing order of frequency were MSK (n =116, 42.2%), PICC (n =51, 18.5%), cardiopulmonary (n = 35, 12.7%), other (n = 30, 10.9%), GI/GU (n = 23, 8.4%), neurological (n = 13, 4.7%), and infection (n = 7, 2.5%) (Fig. 1). When examining only the subcohort of 51 PICC-related ED visits, the most common PICC-specific complications were: malposition/readjustment (n = 21, 41.2%), occlusion (n = 18, 35.3%), infection (n = 4, 7.8%), thrombosis (n = 3, 5.9%), removal (n = 2, 3.9%), cellulitis (n = 2, 3.9%), and hematoma (n = 1, 2.0%) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1. Primary reasons for 90-day ED visits after PICC-line placement: This figure shows the distribution of reasons for ED presentation in the 90-day postoperative period and the breakdown of those ED visits that led to readmissions. Note. ED, emergency department; PICC, peripherally inserted central catheter; MSK, musculoskeletal; GI/GU, gastrointestinal/genitourinary.

Fig. 2. PICC-related reasons for 90-day ED visits. This figure shows the distribution of specific PICC-related complications leading to 90-day ED visits. Note. PICC, peripherally inserted central catheter; ED, emergency department.

Overall, there were 284 (31.9%) readmissions and only 5 were PICC related. The primary categories for readmission in descending order were MSK (n = 166, 58.5%), cardiopulmonary (n = 30, 10.6%), other (n = 28, 9.9%), GI/GU (n = 21, 7.4%), PICC (n = 19, 6.7%), neurological (n = 13, 4.6%), and infection (n = 7, 2.5%). An additional analysis of readmissions specifically originating from the 275 90-day ED visits identified 152 readmissions (55.3%). The primary categories for readmission originating from an ED visit in decreasing order of frequency were MSK (n = 77, 66.4%), cardiopulmonary (n = 25, 71.4%), GI/GU (n = 15, 65.2%), other (n = 14, 46.7%), neurological (n = 9, 69.2%), infection (n = 7, 100.0%), and PICC (n = 5, 9.8%) (Fig. 1).

A multivariable logistic regression model controlling for age, sex, race, drug use, and Elixhauser comorbidity score, demonstrated that younger age (odds ratio [OR], 0.98; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.95–1.00; P = .035) and non-White race (OR, 2.24; 95% CI, 1.24–4.04; P = .007) were associated with PICC-related ED visits (Table 2). Another multivariate regression controlling for all Elixhauser comorbidities found that no specific comorbidity predicted PICC-related ED visit.

Table 2. Multivariate Regression for PICC-related ED visits a

Note. PICC, peripherally inserted central catheter; ED, emergency department; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

a Multivariate logistic regression controlling for age, sex, race, drug use, and Elixhauser comorbidity score to explore factors predictive of PICC-related ED visits.

Discussion

Our data show that PICC complications within a PJI cohort required ED utilization at a rate of 18.5% in the 90-day postoperative window and were the second most common reason for ED presentation. Despite high ED utilization, PICC-related issues were the least common reason for readmission after ED visit, with only 9.8% of PICC-related ED visits requiring readmission. Median time from discharge to PICC ED presentation was 16.4 days. Subgroup analysis demonstrated PICC malposition/readjustment and occlusion to be the most common reasons for PICC ED presentation. This increased and early rate of presentation to the ED warrants consideration of patient optimization prior to PICC placement in addition to further research on OPAT duration and complication management.

Given the paucity of available data regarding PICC complications, it is difficult to contextualize our institution’s PICC-related complication rates. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to address postoperative ED utilization for PICC complications in the setting of PJI. The OVIVA trial, which compared oral versus intravenous antibiotics for all-cause bone and joint infection, did record PICC-line complications as a secondary end point. Reference Li, Rombach and Zambellas2 They reported a lower PICC complication rate of 9.4%; however, they did not include mechanical complications leading to catheter removal in that proportion. After including the patients who had difficulty with IV access or antibiotic administration, the rate of intravenous catheter complications is ∼17%, comparable to our reported 18.5%. Another study by Underwood et al Reference Underwood, Marks, Collins, Logan and Pollara3 quantified adverse effects in patients who receive intravenous antimicrobial therapy for any indication. Despite having a relatively limited subcohort, this study noted a complication rate of 21.9% in their PICC patients. None of the previous studies performed subanalyses quantifying PICC-specific complications. However, Leroyer et al Reference Leroyer, Lashéras and Marie4 similarly found obstruction and accidental removal to be common complications, but they reported a higher rate of infection in a general PICC population at their institution. Moreover, Grau et al Reference Grau, Clarivet, Lotthe, Bommart and Parer5 and Jumani et al Reference Jumani, Advani, Reich, Gosey and Milstone6 identified complications requiring repositioning to be common PICC-line complications in the general population.

In an analysis of predictors for PICC-related ED visits, multivariate regression identified younger age and non-White race as significant predictors. Previous studies examining the effect of age on PICC complications have yielded mixed results. When analyzing pediatric patients with all-cause PICC lines in the outpatient setting, Kovacich et al Reference Kovacich, Tamma and Advani7 identified younger age as predictive of all-cause PICC complications. In contrast, Valbousquet-Schneider et al Reference Valbousquet Schneider, Duron and Arnaud8 reported that age >70 years was significantly associated with PICC-related complications in orthopaedic inpatients with bone infections. Reference Valbousquet Schneider, Duron and Arnaud8 Our findings are unique in that we studied reasons for ED visits in the outpatient OPAT PJI patient population. Future studies will need to explore this association further, but it is possible that younger patients in the outpatient setting are more active and more likely to dislodge or otherwise malposition their PICC line while performing activities of daily living. Non-White race was another predictor of PICC-related ED visits. Although this is the first study to identify race as a predictor of 90-day ED visit after PICC line placement, Plate et al Reference Plate, Ryan and Bergen9 recently identified Black race as a predictor of 90-day ED visit after total joint arthroplasty. Reference Plate, Ryan and Bergen9 Similarly, Wiley et al Reference Wiley, Carreon and Djurasovic10 identified Black race as a predictor of 90-day ED visits after lumbar spine surgery. Taken together, this data implies that age and race are important sociodemographic predictors of ED utilization after PICC-line placement. Given the difference between the high rate of ED utilization for PICC complications and the relatively low readmission rate for PICC complications, these data offer a unique perspective on a potential area for improvement to minimize excess healthcare resource utilization. That is, quality improvement programs can potentially identify these higher-risk patients for more thorough education and planning for PICC-line management in the outpatient setting prior to discharge.

Regarding the PICC-related ED visits in our study, the median time from discharge to PICC ED visit was 16.4 days. With the increasing push to prescribe shorter intravenous antibiotic durations (eg, 2 weeks) with a planned transition to early oral antibiotics, Reference Bocle, Lavigne and Cellier11 this is an important consideration in potentially improving healthcare utilization. If our patients could have been treated with more expedient intravenous regimens, a number of PICC complications as well as the ensuing ED visits may have been avoided. As the body of literature surrounding OPAT therapy in PJI increases, it will become even more vital to study the utility of decreased duration of intravenous therapy and possible impact on PICC-associated complications.

This study had several limitations. Although 90-day postoperative windows were studied to maximize our ability to capture all PICC-related visits as well as its relevance to current reimbursement models, a more granular review of 30-day and 60-day windows may offer different insights. All patients in this study sought care at a single, academic, tertiary-care referral center. Therefore, the data and interpretation may have the greatest utility at similar institutions. Additionally, most of our patients are discharged home under the care or home health agencies or to nursing homes, which may lead to differences in ED transfer patterns based on agency confidence in management of PICC lines. Our data repository does not capture home health agency or nursing home company, so we were not able to explore differences in utilization by home health agency or nursing home. However, we do aim to alleviate this concern with multiple means of contacting our team for guidance, with pharmacists and other clinicians available to triage PICC concerns at all times of day. Another potential limitation was that patients may have visited local emergency rooms that were not captured in our system. We have mitigated this risk in multiple ways. Patients are specifically instructed to utilize our healthcare system for any problems arising from their PICC line or PJI care. Additionally, pharmacists check in with patients on a weekly to identify issues with care and to direct patients to providers as needed. Additionally, we screen for utilization of outside healthcare system emergency rooms via our EHR interinstitutional data sharing. It is also possible that other socioeconomic factors, including primary language, insurance status, and education level, have an impact on ED utilization or other complications. Our data set did not include these variables and should be explored in future analyses. Furthermore, this cohort was primarily created using billing and coding data, with manual validation for patients who experienced complications. As such, it is inherently limited by the accuracy of the codes used. Last, though the findings in this study were significant, the numbers are limited and assessment of a larger population of patients with PICC complications will be important.

In conclusion, PJI patients in this study demonstrated an 18.5% rate of ED utilization for PICC complications in the 90-day postoperative window. Presentation for these complications occurred at a median of 16.4 days after discharge. The frequent and early presentation for PICC complications demonstrates a need for further investigation on OPAT duration and PICC complication management. Last, if future research predicts that these complications will continue despite all efforts for workflow improvement, it would be reasonable to investigate not only risk factors but also risk adjustment modifiers for this patient population.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript was prepared independent of financial support from third parties.

Financial support

No financial support was provided relevant to this article.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no direct conflicts of interest in the preparation of this manuscript.