To a large extent, the prevailing image of interwar Oxford is shaped by Evelyn Waugh's classic novel Brideshead Revisited and the 1981 television adaptation and 2008 film. Although first published in 1945, the book reflects in part Waugh's undergraduate experiences at Oxford (Hertford College, 1922–1924), not least his involvement with the rich, privileged, and incontrovertibly queer young aesthetes—Harold Acton (Christ Church, 1922–1926) and Brian Howard (Christ Church, 1923–1924) chief among them—in whose company he reveled. The set established Oxford as the epicenter of a new brand of modernist aestheticism, queer chic, which expanded beyond their close-knit clique into a notorious local fad adopted by many Oxford undergraduates who were not, technically, queer.Footnote 1

Literary critics have long struggled to come to grips with the complex homoerotics of Brideshead. Until relatively recently, commentators largely sought to ignore, downplay, or dismiss the novel's queer tropes, deploying some remarkable rhetorical distortions in the process. Harvey Curtis Webster's bewildering statement that “Ryder's long journey to faith starts when he meets and falls in love (not homosexually) with . . . Lord Sebastian” is emblematic of the genre.Footnote 2 More recently, progressive literary scholars such as Peter G. Christensen, David Leon Higdon, and Gregory Woods have sought to rescue Brideshead's homoerotic tropes from critical oblivion, crediting Waugh with creating characters who defy an overly dichotomous division between “heterosexual” and “homosexual” and thus represent the multifarious expressions of human sexuality that Waugh experienced at Oxford and beyond.Footnote 3 Such an approach is by no means straightforward and must negotiate Waugh's complex mindset and the often submerged queer sensibilities of his age.

Comparable issues of interpretation pervade the homoerotics of Oxford University, its dons, and students during the interwar period and, by default, those of Cambridge. Still largely playgrounds for affluent and otherwise advantaged young people to occupy themselves as they pleased, both universities existed as collections of cloistered communities that revered intimate same-sex (overwhelmingly male) bonding as a superior means of elite social organization and mode of nurturing a lifelong tribal identity. Notwithstanding the inextricable Oxbridge association with British establishment culture, it is too little appreciated that these multidimensional same-sex environments, simultaneously geographical, institutional, and ideological spaces, long provided a haven for many men and, increasingly through the twentieth century, women, whose gender identities and sexualities countered prescribed categories of expression. These extraordinary circumstances were responsible for releasing profound social and intellectual currents that had enormous impact on the course of British queer history. Many scholars will be familiar with the towering figure of Maurice Bowra (New College, 1916–17, 1920–1922; fellow of Wadham College from 1922), the indomitable warden of Wadham College (1938–1970), whose homosexual exploits, bawdy poetry, and stupefying quips (such as “Buggery was invented to fill that awkward hour between evensong and cocktails”) are now the stuff of Oxford legend.Footnote 4 For the most part, however, Britain's historic university cities have yet to be situated within a now vibrant and rapidly developing historiographical field; largely founded on pioneering work on London's queer history by Matt Cook, Matt Houlbrook, and others, this body of scholarship seeks to map shifting sexual and gender identities and behaviors, and the vicissitudes of modern British queer history, onto the complexities of spatial dynamics. Recently, insightful projects by Historic England and the National Trust have focused attention on the often-surprising queer histories of remote heritage locations, expanding the scope of scholarship beyond a primary focus on the development of gay “scenes” in urban conurbations to embrace diverse modes of queer living and loving in modern Britain.Footnote 5

To date, only Ryan Linkof has directly implicated interwar Oxford in this scenario, usefully discussing the impact of homosexual or bisexual male graduates such as Patrick Balfour (Balliol College, 1922–1925), Tom Driberg (Christ Church, 1924–1927), and Beverley Nichols (Balliol College, 1917–1921) on London's popular print culture.Footnote 6 Linkof establishes an important association between the queer aestheticism of “Brideshead” Oxford with the broader patterns of British queer history through the 1920s, an inspired approach that has much wider application. The emergence of modern gender and sexual identities in Britain during the critical interwar period and into the postwar era was spearheaded, to a significant extent, by educated queer men and women who had the privileges and opportunities to articulate new, modernist queer subjectivities on a relatively broad cultural canvas. A more concerted historical analysis of the circumstances of their education, a major undertaking that necessitates scrutiny not just of the queer dynamics of universities but also Britain's public schools, is therefore desirable.

Reaching toward this objective, in this article I seek to expand awareness of interwar Oxford as an important focal point of queer modernism by exploring how romantic and sexual relationships between Oxford's male undergraduates were experienced during the 1930s.Footnote 7 The decade has already been identified as critical in the way that gender and sexual variance was perceived and represented in British society, standing in many ways in sharp contrast to the relative freedom of the 1920s and laying much of the groundwork for the dramatic postwar scene. Houlbrook, for example, discusses the rise of “pansy cases” in London's courts during the 1930s, while Alison Oram has charted the emergence of the “sex change” story in Britain's tabloid newspapers through the decade.Footnote 8

I begin by charting the shifting spatial, institutional, and conceptual dynamics that increasingly through the 1930s robbed Oxford's aesthetes of the kudos they had enjoyed through the 1920s but nonetheless maintained Oxford as an extraordinary queer locality both in terms of expression and repression of queer lives and loves. In doing so, I draw on autobiographies, biographies, and obituaries of Oxford's renowned male alumni, as well as relevant articles in the university's several student publications (mainly the Cherwell and Isis), books about Oxford (a popular genre through the interwar period), and archival sources. Narratives relating to Oxford's queer aesthetes, so plentiful for the “Brideshead” era, became sparser through the 1930s as erotic relationships between male undergraduates were driven ever further behind closed doors amid a darkening economic and political climate. Along with a palpable regression in forms of expression, a changing rhetoric is also apparent, with the impact of pernicious medical concepts of sexuality conspiring to align the university's aesthetes more strictly within a modernist hetero-homo binary.

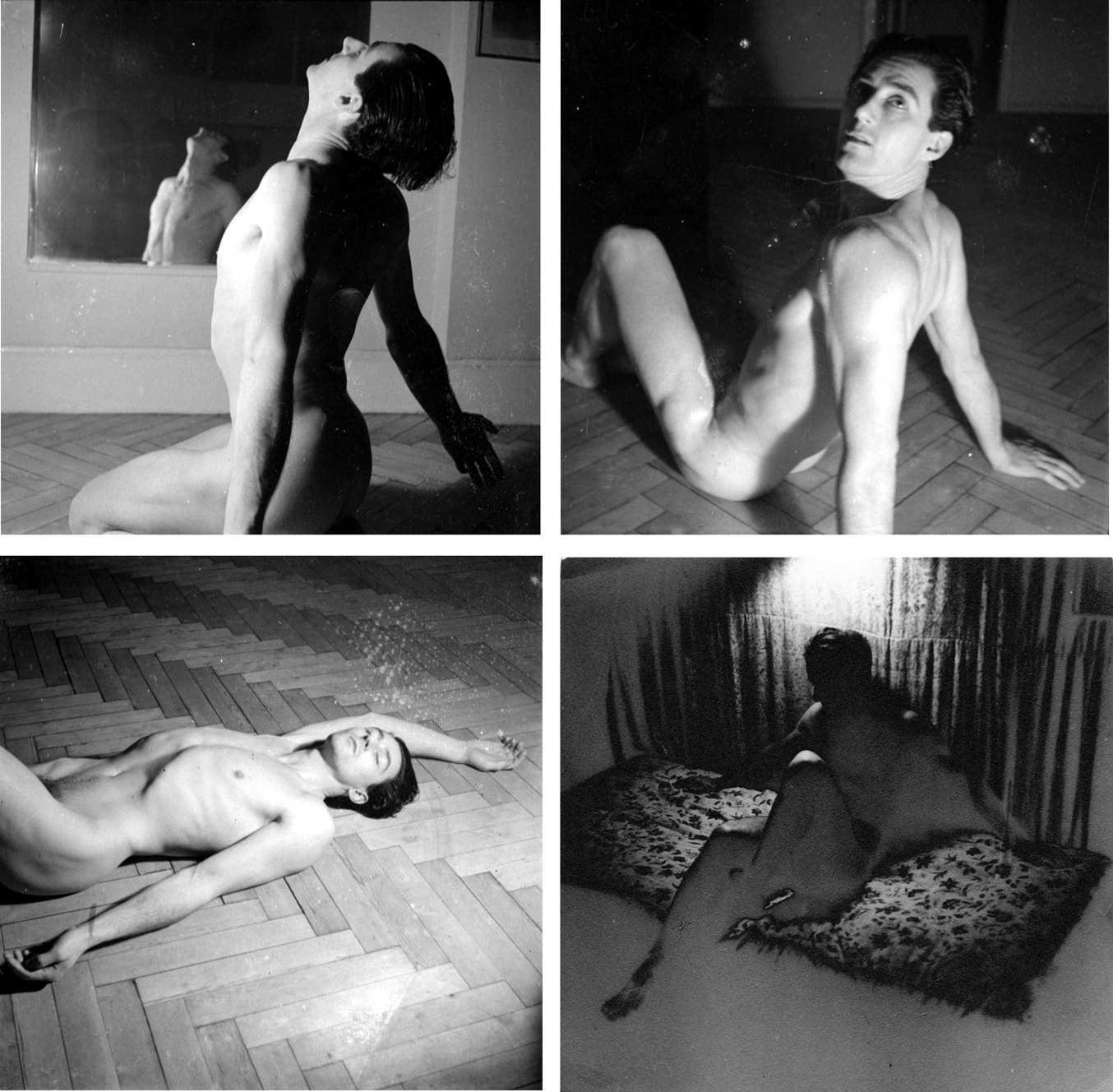

In the second part of the article, I seek to counter the decline of written sources relating to queer lives at Oxford through the 1930s by introducing to scholarship the resplendently homoerotic photographs of the Russian émigré photographer Cyril Arapoff. Resident in Oxford between 1933 and 1939, Arapoff photographed many and varied subjects during his time in the city and although he is now best remembered for his documentary images of London's slums, his studies of nude and seminude young men demonstrate a queer modernist sensibility unique in early and mid-twentieth-century photography. In conjunction with such textual evidence that exists for the period, the photographs offer a springboard for further exploration of aspects of Oxford's queer 1930s history—specifically, the dynamic associations between Oxford's vibrant dance and drama scene and that of London, and the recognition of Oxford's various bathing spots as centers for “homosexual rendezvous” (to borrow a term used by Houlbrook) and moral reprobation.Footnote 9 Arapoff's images evidence the continued, if subdued, integration of queer lives at Oxford through a period when such lives were rarely articulated in writing, either at the time or retrospectively.

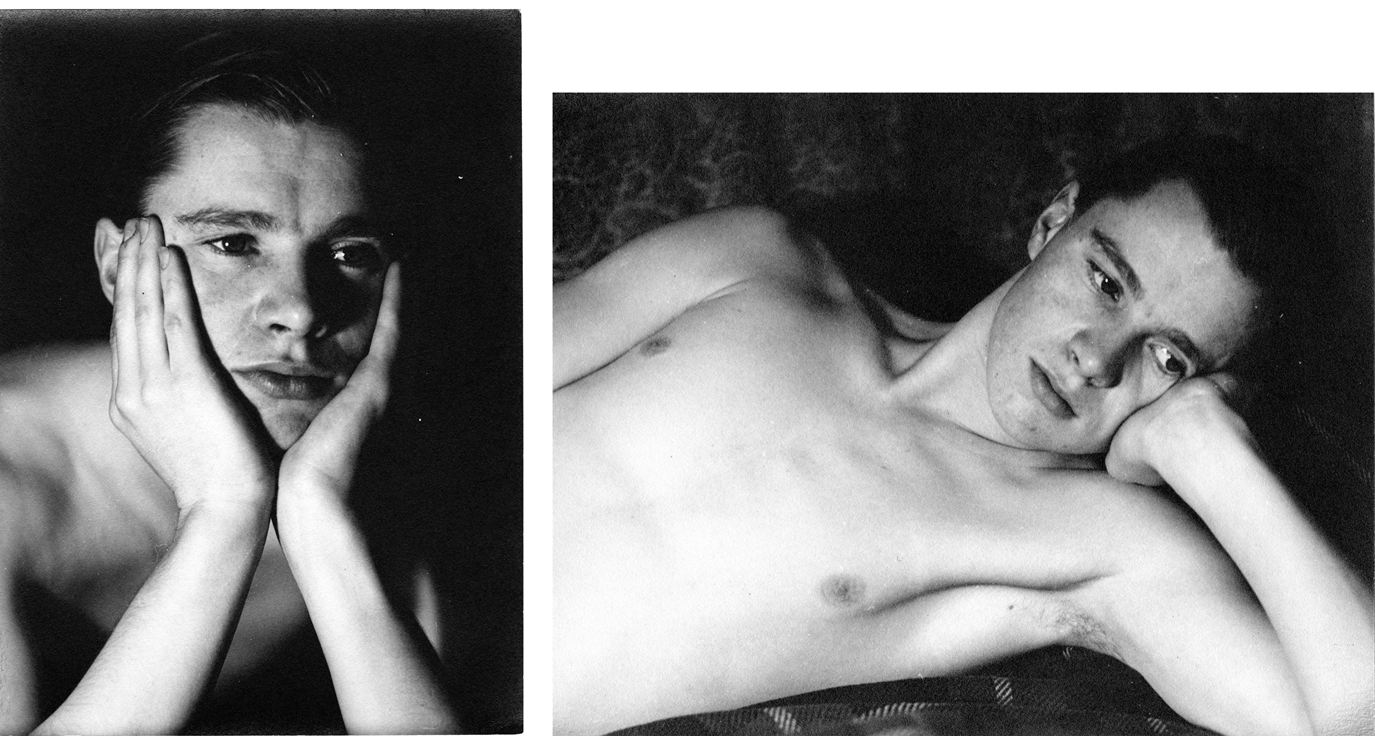

Figure 1 Young man photographed by Cyril Arapoff. © Images & Voices, Oxfordshire County Council.

Notably in 1930s Oxford, expressions of queer lives sometimes involved other queer localities (especially London) and transportation routes. This situation underscores the need for more comprehensive queer histories of modern Britain (and beyond), and it is hoped that this article will help the process of inclusion of many more queer localities in British queer history in the near future.

From “Romanticism” to “Homosexuality”

Oxford as a small city (“town”) was transforming through the 1930s. Vibrant car manufacturing and publishing industries largely protected local people from the Depression, but the rapid expansion of the city and the increasing presence of cars and motorcycles on Oxford's roads underscored that modernity was at last catching up with a historic university culture. Oxford as a university (“gown”) is an especially complex matrix of environments with its own histories, traditions, rituals, vocabulary, economics, spaces, identities, hierarchies, and systems of authority and policing—in Jan Morris's words, “a whole manner of thought, an outlook, almost a civilization”—often bemusing to outsiders and warranting particular attention by historians.Footnote 10 From the late 1920s (the General Strike of 1926 can usefully be taken as a moment of change), members of the university faced a torrent of media-driven indictments about the supposed “degeneracy” of standards and undergraduates. Amid such changing times, Oxford's long-standing traditions of queer aestheticism and private same-sex romances between male undergraduates increasingly became objects of critical scrutiny and thereby deeply enmeshed with Oxford's gradual modernization.Footnote 11

In 1930, Degenerate Oxford? A Critical Study of Modern University Life, by the author and actor Terence Greenidge (Hertford College, 1920–1924), a friend of Evelyn Waugh, proffered a lengthy and unprecedented assessment of homoeroticism among Oxford's male undergraduates. Terming this phenomenon “Romanticism,” Greenidge supplied interesting nuances to how such relationships were pursued. For example, although his narrative on Romanticism features in a chapter on aesthetes, he well understood that romantic affections transgressed the traditional division of Oxford's male undergraduates between the aesthete (“arty”) and athlete (“hearty”) and, indeed, ensured that this traditional dichotomy functioned within sustainable boundaries. The chief objects of hearties’ attentions, he wrote, were the waitresses at Oxford's popular George Restaurant and the girls they had left at home, but amid the hearty “blind” (drunken party), “even in Athletic Magdalen” College and among the torpid rowing crews, the most unlikely people dabbled in Romanticism, “as it were by accident and scarcely conscious of what they were doing.”Footnote 12 Greenidge had himself, while at Hertford College, been an admirer of a hearty, giving up smoking and keeping fit to impress his beloved. Still, judging by Greenidge's remarks, the rules of the game appear to have varied across the aesthete/athlete dichotomy. Having first declared that the same-sex romances of Oxford's manly rowers were confided to him only in the “unrestrained atmosphere of a Wardour Street café” (that is, in London), Greenidge subsequently stated that affections between male undergraduates were openly discussed (“as a matter of course and quite above board”) in the smoking rooms of respectable varsity institutions; he cited the Oxford University Dramatic Society clubroom on George Street.Footnote 13 The two assertions are not necessarily incompatible; in enduring Oxbridge fashion, the unwritten rules for discussing (or not discussing) the homoeroticism of athletes were different from those governing discussion of the homoeroticism of aesthetes.

After mounting a defense of Romanticism, Greenidge assessed its pitfalls, finally asserting that romantic attachments between male undergraduates could be remedied by fully inclusive coeducation. Ostensibly, his lengthy appraisal of Romanticism responded to popular (media) criticisms of Oxford's aesthetes as “degenerate, decadent and in the main unhealthy.”Footnote 14 His narrative evidences awareness that increasingly prominent public debates about “homosexuality” and its nature and significance in medicine, law, and society were encroaching on cherished Oxford traditions and affecting the university's reputation. As such, he presented same-sex romances between male students for the first time as an object of analysis within a wider debate about undergraduate life and Oxford's place in a rapidly changing world.

Degenerate Oxford? was reviewed in Oxford and nationally, opinions varying widely.Footnote 15 A repeated view was that the work was outdated, relating to Greenidge's time at Oxford during the early 1920s rather than Oxford in 1930. It simply did not reflect significant changes in the university's cultural life after Greenidge and the rest of the “Brideshead” generation moved on. Although Oxford was not hit hard by the Depression relative to other localities in Britain, national economic instability, rising unemployment, and the growing threats posed by Hitler and Mussolini rendered the university's monastic existence ever more archaic and impractical to modern British public life. As Dave Renton has discussed, fascists were making their violent presence felt in the city by the late 1920s, a situation that Oxford's socialists, communists, and other antifascists met with resistance.Footnote 16 As the twentieth century finally caught up with Oxford, socialism and communism displaced the queer chic of the 1920s, and in this heavier, politicized atmosphere there was little room for lazy, self-indulgent, and vice-ridden aesthetes, as they were largely perceived and represented.

The hegemony of politics in Oxford's cultural life was accentuated by the notorious debate “that this House will in no circumstances fight for its King and Country” at the Oxford Union on 9 February 1933. The motion was carried by 275 to 153 votes, to the outrage of the national press.Footnote 17 With Oxford's queer aesthetes already enmeshed in public debates about the supposed degeneracy of the university, the sensational coverage suggested they were at least partly to blame for the encroachment of leftist politics at one of the country's elite institutions. The Daily Express (13 February 1933) asserted, “There is no question but that the woozy-minded Communists, the practical jokers, and the sexual indeterminates of Oxford have scored a great success in the publicity that has followed this victory at the Oxford Union . . . Even the plea of immaturity or the irresistible passion of the undergraduate for posing cannot excuse such a contemptible and indecent action as the passing of that resolution.”Footnote 18 Joseph Banister, the venomously anti-Semitic author of England under the Jews (1901), proffered the view from his London home to the Isis (23 February 1933) that, while he did not know much about the Oxford Union, judging from the vote, it “consists chiefly of aliens and perverts.” He ended his letter, “It is a pity that the sweet creatures’ names are not published. The police would find them useful.”Footnote 19

Such rhetoric (“sexual indeterminates”; “perverts”) aped pernicious, medico-scientific concepts of sexuality—sexology—which, by the 1930s, found many expressions. Freudian and pseudo-Freudian precepts alleged homosexuals were immature; psychiatric precepts maintained psychological instability; physiological approaches were taken to indicate a hidden genetic or endocrinological intersexuality. However, such ideas had little apparent impact at Oxford prior to the 1930s; in the pages of the Cherwell and Isis, the names of Freud and Jung were little more than jokes.Footnote 20 In Degenerate Oxford?, Greenidge took pains to distance Romanticism both from the specter of sodomy and the degenerate connotations of “homosexuality,” although he nonetheless echoed modernist sexological precepts. He did not like the term “homosexuality”: “It sounds very sinister, and also denotes more than I really intend”; he also rejected “romantic friendship” as “being rather a mouthful.”Footnote 21 Romanticism at Oxford, he insisted, was different, “a special perquisite of the Æsthete,” and romances between male undergraduates were not generally pursued “to lengths which would engender conflicts with our criminal code.”Footnote 22 One of his recurring arguments is that Romanticism was an affectation of Oxford's young men as they passed through a transitional stage of development. They were therefore “immature” enough to find satisfaction in Platonic affection, although, Greenidge admitted, “Queer deeds may occasionally get done among those who come from over-emancipated Public Schools.”Footnote 23 Although Britain's leading sexologist, Havelock Ellis, had taught many to view sex “coldly and clearly,” Greenidge maintained that the majority of Oxford romances were platonic and could be likened “to a warm, misty July morning.”Footnote 24 He therefore sought to distance Romanticism from the morbid connotations of the medicalized category of “homosexuality,” delineating a bespoke typology of homoeroticism and homoerotically inclined young men and thereby demarcating same-sex affections at Oxford from those types of sexual perversion upon which sexologists such as Ellis waxed lyrical.

Nobody else echoed Greenidge's distinctions. Reflecting the harsher cultural climate, subsequent published appraisals of homoeroticism at Oxford through the 1930s are discernibly more clinical, statistical, and simplistic, generally preferring to discuss “homosexuality” or “perversion” in medicalized rhetoric without the subtleties Greenidge had been at pains to delineate. John Connell (pseudonym of John Henry Robertson) (Balliol College, 1928–1931), who became a prolific journalist and author after leaving Oxford, penned a remarkable piece, “Purveyors of Sex-Bunk” for Red Rags: Essays of Hate from Oxford (1933), a collection of provocative essays that sought to give Oxford's undergraduates and recent graduates more of a voice, and a platform for some tit-for-tat whining, in the public debates raging about the alleged degeneracy of the university and its students.Footnote 25 Connell's contribution has an interesting backstory. Just after leaving Oxford, he had complained in the pages of the Week-End Review (21 November 1931) about the conviction of Augustine Joseph Hull, a twenty-one-year-old man from St. Helens, Merseyside, for inciting another man to commit an act of gross indecency. Connell questioned that justice was meted out at the trial: “The pathetic, puzzled victim of an abnormality which he cannot control is treated as a reasonable moral being, and has to suffer for transgressing a code he cannot recognise. That this unfortunate being was someone desperately in need of help seems to have occurred to nobody at all in that court of justice.”Footnote 26 Following Connell's letter, a campaign to defend Hull, spearheaded by the Week-End Review, led to his transfer to a prison near London, where he received medical treatment. Naively, Connell thought that this action by the home secretary negated the harshness of the original conviction.

Despite helping to produce what he thought was a better outcome for Hull, Connell found his experience of complaining so publicly about the conviction demoralizing. His essay in Red Rags describes how he had become “the unwilling and sullenly infuriated recipient of every kind of outrageous bosh about sex.”Footnote 27 His tabloid-journalistic style of writing about sex is a stark contrast to Greenidge's formal narrative in Degenerate Oxford? (Between penning his letter to the Week-End Review and his essay for Red Rags, Connell joined the staff of the Evening News, remaining with the newspaper for his whole career.) Connell slammed the “bunk purveyors” and “sex sillies” who petitioned him, both “the raging ‘antis’” and “the slobbery ‘pros.’”Footnote 28 He reiterated his view that Hull was “a case of grave psychical disorder” who required medical treatment in the same way “as a person after a bad car accident, or with an unpleasant skin disease, is treated.”Footnote 29 He fervently maintained that the only people who were qualified to talk about sex were “medical men and jurists who have made a properly scientific study of the whole matter” (he subsequently included priests).Footnote 30 What came across as a bold, impassioned plea for clemency in the Week-End Review becomes in Red Rags a self-pitying rant and an escalation of the argument that individuals such as Hull were profoundly pathological.

Following Red Rags, other Oxford-related publications similarly discussed sex in a colloquial student-speak that may well have been in common usage verbally but was new to Oxford's print culture. In a chapter entitled “OxSex” in his book Letter to Oxford (1933), Tom Harrisson (a Cambridge graduate) echoed the blasé tone of Connell's Red Rags essay (which he referenced), thereby establishing a pejorative, homophobic rhetoric as the new norm for discussing homoeroticism at Oxford in print. “Ox is full of perverts—I guess twenty per cent at least,” he wrote. “This naturally excludes masturbators, who are the british [sic] norm. Some of the flashest perverts in the world learnt their stuff at Ox.” He also asserted, “Pervert parties are a University feature. Details are unprintable and I hope to publish them shortly.”Footnote 31 The rhetoric of “perversion”—a far cry from Greenidge's Romanticism—took the discussion of homoeroticism at Oxford further from older traditions of queer aestheticism and passionate friendships between arties and hearties that characterized the “Brideshead” generation.

Given the increasing disapprobation in attitudes toward aesthetes and homoeroticism expressed through the 1930s, it is unsurprising that accounts relating to lived queer experiences at Oxford became more sparse. Intimate same-sex relationships clearly flourished in certain undergraduate circles through the decade, much as they had through the 1920s, but for the most part they were conducted (to borrow a phrase from Brideshead) “so much in the shadows,” providing problems of evidence for the historian.Footnote 32 Glimpses of queer lives at Oxford in autobiographies and biographies (including obituaries), such that exist, are invaluable and reveal much about the spatial, institutional, and psychological dynamics as untold numbers of young men negotiated their gender and sexual identities amid changing times. Richard (“Dick”) Crossman (New College, 1926–1930), in an early diary entry, described an Easter holiday with another young poet who “kept me in a little white-washed room for a fortnight because his mouth was against mine and we were completely together.”Footnote 33 Not much is known about Peter Watson's experiences at Oxford (St. John's College, 1927–1929 or 1930) except for his lack of academic achievement (he appears to have spent much of his time enjoying the gay delights of Munich). Despite immense wealth, he was sent down (expelled) after repeated failure. Still, a postcard sent to his friend Cyril Connolly (Balliol College, 1922–1925) in 1945 is suggestive; above a drawing of a little house that he identified as “Οξφόρδη” (Oxford), he wrote (also in Greek), “In this house I was born.”Footnote 34

James Lees-Milne (Magdalen, 1928–1931) engaged in “orgies of a fairly harmless kind” and “casual romps,” according to Michael Bloch, including sex with Alan Lennox-Boyd (Christ Church, 1923–1927) and George Lennox-Boyd (Christ Church, 1928–1930).Footnote 35 During 1931, a more serious romance briefly blossomed between Lees-Milne and the actor John Gielgud. “For six weeks I was infatuated with him,” Lees-Milne recalled in his diary. “Then it passed like a cloud.”Footnote 36 Although Gielgud (never a member of the university) was already a major star on the London stage and in films, he retained strong professional and personal links with Oxford where his career had taken off with J. B. Fagan's repertory company, based at the Playhouse on Woodstock Road in 1924. The six-week affair was largely conducted in the relative safety of the lavish Spread Eagle Hotel in Thame, an upmarket town about thirteen miles from Oxford and a favorite hangout of Oxford aesthetes.

Gielgud's queering influence among Oxford undergraduates is also evident through his close involvement with both of Oxford's theaters (Playhouse and New Theatre) and the Oxford University Dramatic Society, with which Gielgud made his directorial debut with a production of Romeo and Juliet in February 1932. Notably, most of Oxford's known queer alumni of the 1930s involved themselves with the society or college theatrical productions, a significant shift from what had gone before.Footnote 37 Scholars have long recognized historical associations between the entertainment professions and queer sexualities and gender variance. For the modern era, Matt Cook writes of the notorious reputations of London's West End theaters, both as establishments where gender and sexual diversity were represented on stage and as places where men-loving men met.Footnote 38 Matt Houlbrook picks up the trail for the mid-twentieth century, describing how London's cinemas, music halls, and theaters provided gay men with meeting and cruising spaces that were relatively safer and less conspicuous than outdoor sites.Footnote 39 Elsewhere, attention (largely biographical) has focused on individual actors and singers such as Noël Coward, Ivor Novello, and Gielgud and drag artists such as Douglas Byng. There is scope for a more integrated approach; individual biographies often relate a broader geographical span to the queer lives of actors and other performers beyond London, indicating that Britain's entertainment professions provided a useful modus operandi for the countrywide development and transmission of significant aspects of modern British queer culture. Gielgud is a prime example. His contribution to queer history is often reduced to his conviction (in London) for “importuning male persons for immoral purposes” in October 1953, yet he traversed an extensive international cultural and geographical landscape, professionally and privately. Oxford, with its vibrant culture of student and professional drama, was one of his favorite queer localities.

In his biography of Gielgud, Sheridan Morley described the Oxford University Dramatic Society as “a distinctly homosexual society with some very good-looking young men.”Footnote 40 Lamenting how he felt ostracized as a heterosexual poet at Oxford, Louis MacNeice (Merton College, 1926–1930) claimed that in order to get on in the society, “it still helped if one were or pretended to be homosexual,” a situation, he wrote, that prevented him from joining the company.Footnote 41 With a nosedive in general attitudes toward Oxford's Wildean aesthetes, the society's flourishing culture of drama increasingly accommodated queer male undergraduates through the 1930s. Student theater at Oxford was potentially a springboard for a career in the entertainment professions and thus attracted aspiring young “theatrical types” to the university. Leading actors and directors of the day were invited to work with Oxford's young thespians on major productions of the society, which were attended by London's foremost critics. High-profile actresses (among them Peggy Ashcroft, Edith Evans, Vivian Leigh, Margaret Rawlings, and Jessica Tandy) were imported to play female roles. Still, through the 1930s, the society was a haven—the last outpost—for Oxford's bespoke brand of queer chic. Theater culture's relative tolerance of camp and homo-smutty humor, drag, queer identities, and gay sex provided Oxford's student actors with sufficiently delineated space and ideological protection for some of the twentieth-century's most eminent queer playwrights, directors, and actors to establish themselves within the profession, even through the darkest days of legal and sociopolitical repression of homosexuality and homosexuals.

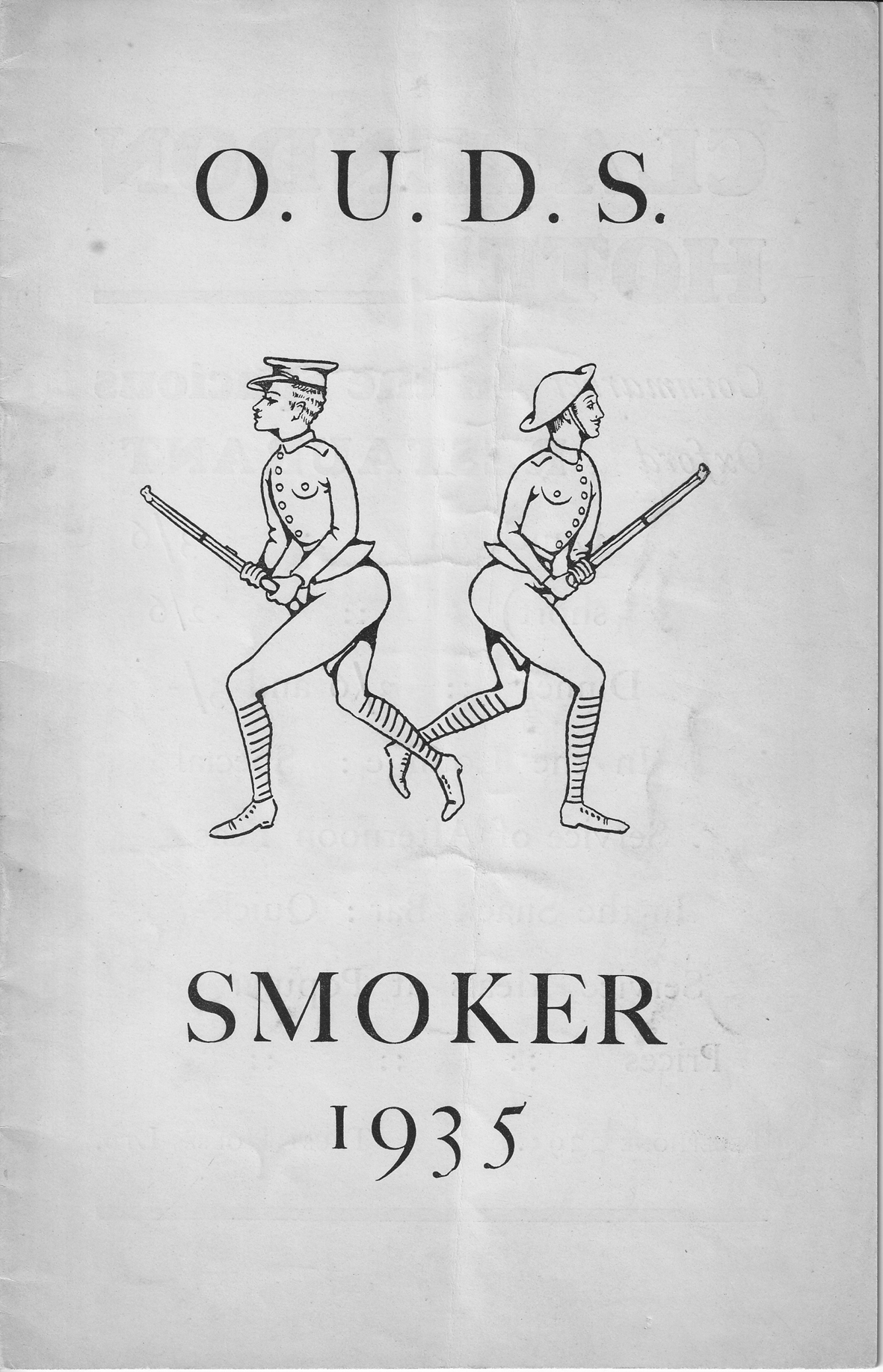

Terence Rattigan read history at Trinity College between 1930 and 1933, leaving without taking his degree following the overnight success of his first play, First Episode, a collaboration with Philip Heimann.Footnote 42 Although he appeared in a number of minor roles in productions of the Oxford University Dramatic Society, Rattigan established himself with the company largely through “Smokers” (figure 2)—annual in-house revues, notoriously camp and risqué, performed for society members and their guests.Footnote 43 He delighted the crowd with turns as Lady Diana Cootigan (a play on the phrase “as queer as a coot”), aping the drag act of Douglas Byng.Footnote 44 He also fell in with Gielgud (whom he idolized) and John Perry, Gielgud's partner, regularly attending lively weekend parties at their secluded residence near Henley-on-Thames in Oxfordshire. Notwithstanding, while acknowledging that Rattigan freely engaged in same-sex affairs throughout his time as a student, Michael Darlow, Rattigan's most recent biographer, has cautioned that the parameters within which Rattigan could engage in such relationships were circumscribed. Like so many of his generation, Rattigan was torn about his sexuality; only his most intimate circle of friends at Oxford knew he slept with other men.

Figure 2 Program from the March 1935 Oxford University Dramatic Society Smoker (titled “Her Privates We”). The figure on the left has painted eyelashes and rouged lips. © Images & Voices, Oxfordshire County Council

Other society members through the 1930s went on to achieve considerable success in film, television, and theater and played significant roles in modern British queer history. These include Frith Banbury, who came up to Hertford College to study modern languages in 1930 but spent his time acting and socializing (he left in 1931 to attend drama school); Richard Buckle (Balliol College, 1934–1935); Paul Dehn (Brasenose College, 1931–1934); Peter Glenville (Christ Church, 1932–1935); and Dennis Price (Worcester College, 1933–1936). Another star turn at Smokers was Angus Wilson (Merton College, 1932–1935). Wilson's biographer, Margaret Drabble, relates how, in a novel interpretation of the seven deadly sins, he portrayed Buggery in flame-colored pajamas, holding a madonna lily, to an audience that included Ivor Novello (who, incidentally, had been a chorister at Magdalen College School) and Gladys Cooper, both stars of the day. Other of Wilson's acts included an imitation of the celebrated 1933 Debutante of the Year, Primrose Salt (who appeared as Helen of Troy in the Oxford University Dramatic Society's production of Dr. Faustus in February 1934), and a skit as a comic charlady singing “I've got a boy in India, so I won't be kissed on the lips.” Drabble succinctly captures Wilson's affinity for such turns: “He was a natural in drag.”Footnote 45 In a piece written for a 1977 compilation of reminiscences, My Oxford, Wilson suggests that the queer antics of Oxford's young male thespians did not necessarily result in unrestrained gay orgies, or, if they did, they were selective affairs: “As to the aura of wickedness that still hung round the OUDS from the ’twenties, it never seemed to me to go further than ‘daring’ talk and camp flirtation. From my background of London promiscuity, I thought it all rather absurd. But now I'm inclined to wonder. Despite my gay chatter, I did carry a governessy aura around with me at Oxford and, for all I know, as soon as I left the parties everyone may have relaxed and started to have it off.”Footnote 46 Wilson was likely not missing out on much by way of orgies. Autobiographical and biographical materials relating to queer experiences at Oxford through the 1930s, such that exists, relate few stories of sexual debauch (even of the “harmless” variety attributed to Lees-Milne) such as were stirred up in the popular imagination by Oxford's mythologizers and the national media.

There is some evidence that young men sold gay sex in Oxford, propositioning wealthy students and dons on the streets. In her biography of Wilson (who had a penchant for young working-class men), Drabble recovered a deleted section from his 1977 reflective essay in My Oxford: “I remember only twice when I made pick ups in Oxford's streets (both times what I think would now be called hustlers) and in each case I rapidly withdrew with the sense that this was a London or French holiday activity not to be pursued in Oxford.”Footnote 47 Wilson's reluctance to indulge on home territory indicates that such trade was limited. Feasibly, however, some young male townsfolk may have sought gay sex and some extra cash, or possibly some savvy hustlers traveled from London (or were banished following convictions) in search of rich pickings.

Other factors regulated the degree to which Oxford's male undergraduates could pursue same-sex sexual relationships within the tight-knit university environment through the 1930s. Several sources suggest that homophobia, and internalized homophobia, were increasingly rife. Wilson arrived at Oxford in a state of fear and had a miserable first term listening to blood-curdling screams outside his rooms at Merton as hearties administered “roastings and defenestrations” to their victims.Footnote 48 While by no means acting out the flamboyant aesthete stereotype, Wilson was naturally effeminate; in his own words, “I was very ‘pansy’ in manner and I was very conscious of it.”Footnote 49 Alarmed by fellow students throwing bread at each other at dinner and fearing it was a prelude to something worse, he avoided eating in halls for the entirety of his course (he also disliked the food) and took to taking long, lonely afternoon walks in the countryside lest he be labeled a swot or an aesthete for staying in his rooms. He appears to have avoided being attacked and found friends, not least with the Oxford University Dramatic Society set where his “camp carry-on” found a natural home.Footnote 50 Some Oxonians, especially the dons, evidently took an instant dislike to him. A contemporary, Sylvain Mangeot, recalled, “His appearance was odd; his hair was indescribable and he had an extraordinary camp way of talking which put many people off.”Footnote 51 One of the most prominent dons at Merton, H. W. Garrod, confided to Idris Deane Jones, Wilson's history tutor, that he disliked Wilson's “sissy voice.”Footnote 52

Frith Banbury also recalled that Oxford's arties lived in constant fear of a drubbing by hearties. One of his acquaintances was thrown into the Cherwell for growing his hair too long.Footnote 53 Such attacks were, arguably, part of the ongoing antagonisms between arties and hearties between the wars. Banbury, like Wilson, appears to have escaped attack; nonetheless, accounts of assaults become more common from the late 1920s. John Brown, a student at Ruskin College (1932–1934), an independent college offering education to adults mainly from working-class backgrounds, described one such incident in an article for his local newspaper. Oxford, Brown wrote, “has always been a fertile ground for the hothouse seeds of aestheticism.” He continued: “The aesthetes are easily recognisable by their languid air and effeminate manners. The post-war pre-occupation with sex is manifested by them in various ways, chiefly in imitation of the acknowledged best writers on the subject; imitations which endeavour to make up for their deficiencies in style by their outspokenness. One of the aesthetes, who made himself too objectionable to his fellows, was chased around Tom Quad recently by students armed with whips and blowing hunting horns.”Footnote 54 Given these circumstances, it is perhaps unsurprising that published autobiographical and biographical accounts of same-sex affairs relating to alumni at Oxford through the 1930s become increasingly sparse as the decade progresses. For even the most flamboyant of Oxford's aesthetes, same-sex relationships became too risky and retreated ever further into deeply cloistered spatial and psychological territory.

An exception was the irrepressible Neil Munro (“Bunny”) Roger, who matriculated from Balliol College in 1929, subsequently transferring to the Ruskin School of Drawing (now Ruskin School of Art), then part of the Ashmolean Museum. Oxford lore holds Roger to be one of the great beauties of his generation. It was his habit to attend parties dressed as one of his favorite female movie stars (such as Gloria Swanson or Pola Negri) and seduce other male students. Legend (most likely Roger) held that Swanson saw a picture of him dressed as Norma Desmond and graciously conceded that he was far more beautiful than she. Roger's obituaries maintain that he was sent down from Oxford for “corrupting homosexual practices,” an assertion (also possibly emanating from Roger) echoed elsewhere.Footnote 55 This would be historically interesting if it were so, but records at Balliol College and the university archives tell a more complex story. College meeting minutes show that by June 1930, authorities at Balliol were questioning Roger's academic progress, resolving that he would be sent down if he failed his first-year exams. There is no indication that he was sent down; he is still on the college's books the following year but made the shift to the Ruskin that autumn.Footnote 56 He evidently got into trouble at the Ruskin; a sole surviving index card relating to his time there is marked, “Has talent but unstable character: does not work”; it records that he was eventually ousted in 1932 following “Proctoral difficulties.”Footnote 57 While the comments suggest that Roger's flamboyant homosexuality was wearing the patience of the authorities thin, his apparent failure to work at either Balliol or the Ruskin compounds the situation. He would certainly not be the first (or last) to edit his unsuccessful student history, supplying a reason with a more satisfyingly notorious ring than academic idleness. “Corrupting homosexual practices” is a perfect fit for one of the twentieth century's best-dressed dandies.

Roger's exit from Oxford is representative of the general decline in queer mores. A valuable barometer of the impact of the escalation of a repressively homophobic culture on male undergraduates can be found in Little Victims, a student novel by Richard Rumbold (Christ Church, 1931–1934), president of the Oxford University English Club. Published at precisely the moment when debates about Oxford's place in British national life, and the place of “homosexuals” at Oxford, were raging,Footnote 58 the work has little literary merit but is nonetheless remarkable on several counts. It is an early gay-themed publication of the Fortune Press, the London-based publishing house of Reginald Ashley Caton, distinctive for publishing several novels with queer characters and tropes through the 1930s and beyond.Footnote 59 Despite a disclaimer stating that all its characters were fictitious, Little Victims is largely autobiographical (evidenced by his later memoir and published diary), relating Rumbold's unhappiness, loneliness, and deteriorating mental health as he passes through public school and then Oxford.Footnote 60 As such, the book is a unique, subjective psychological study of the lived experiences of a young, queer male undergraduate (“Christopher Harmsworth”) at Oxford during the early 1930s, its structural and literary flaws emblematic of Rumbold's loneliness and anger.

Little Victims makes depressing reading, less a discourse on the nature of “homosexuality,” as gay-themed novels (including Brideshead) tend to be viewed, and more a study of the crippling effects of homophobic abuses. “Christopher” is deeply wounded by the sexualized culture of his school, ostracized for making queer friends at Oxford, and lumbered with an overly friendly tutor who keeps sex books behind a row of academic books in his rooms. Christopher's own rooms are ransacked by rugby-playing hearties who throw him in a pool of ice-cold water. (This was assuredly a case of art reflecting life; Rumbold's rooms at Christ Church were likewise ransacked, and he was thrown into a fountain.Footnote 61) Along the way Christopher loses his Catholic faith after a priest fobs him off with a meaningless absolution. He does have a bit of fun with his queer friends; an account of a drunken late-night party is one of the highlights of the book. Still, Rumbold paints a bleak picture of queer student life. Ever on the brink of leaving Oxford, Christopher is painfully lonely and deeply resentful toward his family, school, university, and church. Reflecting the eugenic ideology of the era, he laments that his parents did not use contraception and prevent his birth; ultimately he commits suicide.

Inevitably, the publication of Little Victims caused what Montague Summers (who was resident in Oxford during the early 1930s and knew Rumbold) called “the silliest storm in a teacup.”Footnote 62 The work fell into the hands of the bishop of Birmingham, Thomas Leighton Williams, who communicated his displeasure at Rumbold's “foul and offensive” book to Oxford's Roman Catholic chaplain, Ronald Knox, who without warning refused Rumbold the sacrament at Christ Church.Footnote 63 The scandal was a national cause célèbre for a short time during June 1933. The book was duly banned. Soon after, Rumbold was diagnosed with tuberculosis and left Oxford in 1934 without taking his degree. Several sources suggest that Little Victims and the sensation surrounding it caused no small amount of amusement among Oxford's undergraduates. The Cherwell, in particular, was pitiless in its ridicule of Rumbold and his novel.Footnote 64 Nobody protested the banning of the book. Still, Little Victims, and the story of its author, provide rare glimpses of changing sexual mores at Oxford. Such a valuable document of the nosedive in attitudes toward queer students and homoeroticism shifts attention away from the flamboyant antics of the “Brideshead” generation and focuses attention on the production of modernist effeminophobia, homophobia, and their internalized counterparts, which continued to be a characteristic feature of the homoerotics at Oxford through the 1930s and beyond.

The Homoerotic Photographs of Cyril Arapoff

Writing in the Cherwell (26 October 1935) under the title “Is Oxford Degenerate?”, editor Peter Dwyer (Keble College, 1933–1936) proffered an extraordinary defense of the (unspecified) transient sexual relationships of Oxford's undergraduates: “Ours is essentially a tragic generation. Born in the turmoil and bloodshed, the suicidal folly and the bestiality of a great war, passing our lives in the midst of the social and economic upheaval which resulted, we are likely to die prematurely in another and yet more violent conflict.” Little wonder, then, that theirs was “a degenerate and an embittered generation”:

It is perhaps the freedom of our attitude towards sex which has most earned us the title of degenerates. The older generation were able to build up for themselves a conception of a long and enduring love, by reason of the apparently secure conditions under which they lived; and those who were prevented by the war from realizing this ideal were cut off too suddenly for it to affect fundamentally their attitude. But to us, faced with the prospect of sudden death, love is something to be found and taken quickly, enjoyed while it is possible. And because of this inevitable approach to sex, because we go to it fearing to find something that cannot last, it has lost for us its permanency. Every new emotion, every new experience we feel may be our last.

If Oxford's undergraduates were degenerate, Dwyer ended, then they were so by necessity, not choice: “Pride and respectability, permanency in love, glory and renown are not for the people that walk in darkness.”Footnote 65

Dwyer's editorial was a spirited, emotive defense of the romances of Oxford's undergraduates, whatever form they took, but it was also the last of its kind to appear in the student press for years. Discourse about the role of Oxford's sexual mores in bringing about the supposed degeneracy of the university continued to feature in Oxford's undergraduate journals, but from the mid-1930s it was essentially a one-sided conversation that perpetuated a pernicious sexological rhetoric and maintained that “homosexuality” or “perversion” was less prevalent at Oxford than it had been a decade before. In Oxford Limited (1937), for example, Keith Briant (Merton College, 1931–1936) estimated the number of “homosexuals” at Oxford at 10 percent—half what it used to be, he wrote, “when homosexuality was fashionable and homosexual parties a not uncommon feature of University life.”Footnote 66 Whatever (certainly limited) credence can by be given to such statistical assertions, it is indubitably the case that it was no longer chic to be queer at Oxford, a situation that undoubtedly fueled a regression of queer identities and sexualities into deeply cloistered psychological and spatial territory and a common perception that there were fewer queer people and fewer same-sex affairs through the period.

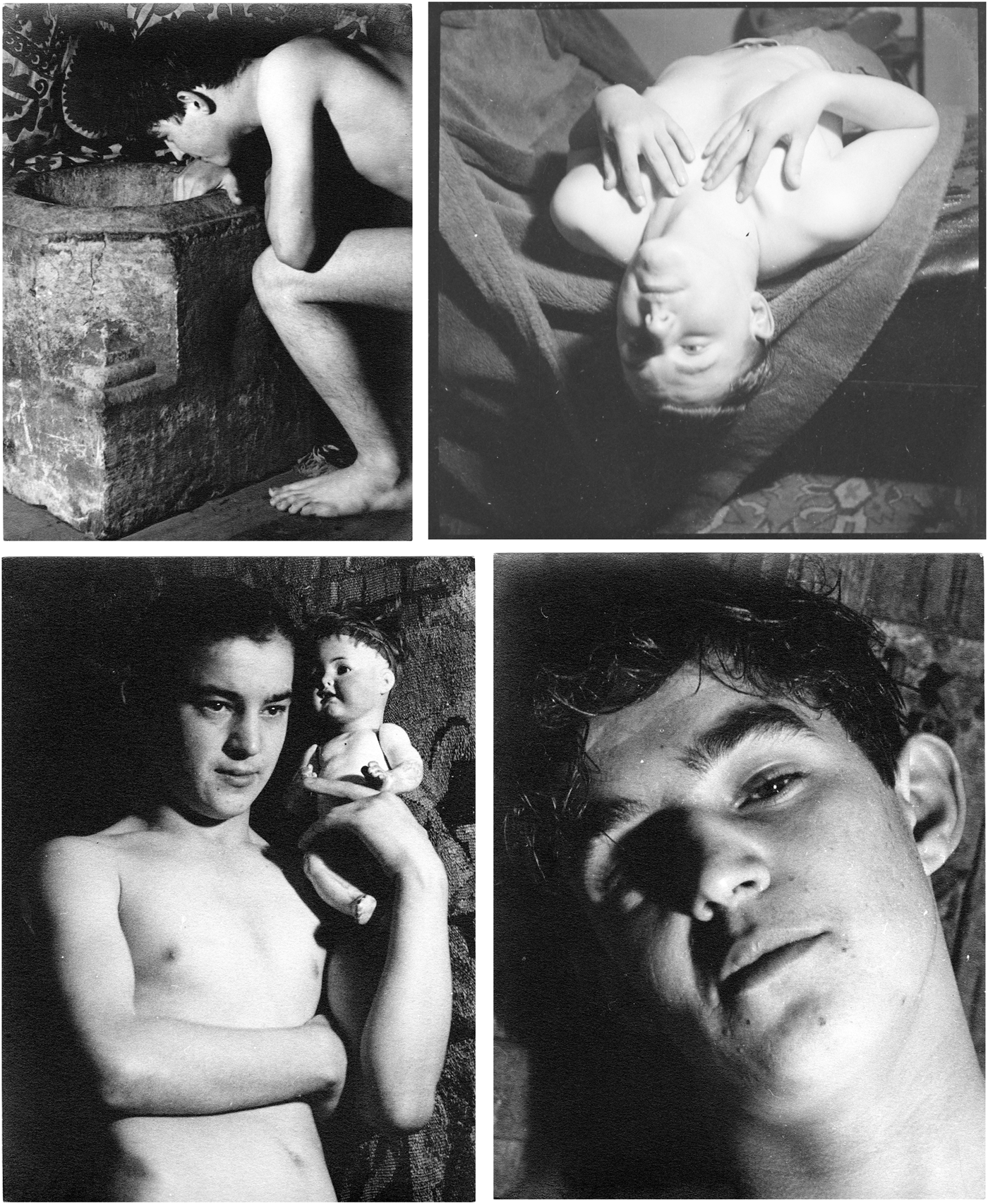

Given this steady regression of attitudes to aesthetes and homoeroticism, the discovery of several nude and seminude studies of young men by the Russian émigré photographer Cyril Arapoff is especially valuable. The images depict a variety of subjects and settings and convey a homoerotic subjectivity that ventures beyond the simple fact that young men are posing in intimate ways for a male gaze. Although other photographers produced homoerotic photographs of young men through the interwar period in Britain and elsewhere (discussed below), the documentary style and queer motifs of Arapoff's images make them unique for the period. Yet the photographs are often perplexing. Arapoff was clearly a man of images, not letters, and there is little supporting textual evidence to help interpret these extraordinary pictures. Cursory annotations, including names, on some of the prints are often puzzling, possibly referring to individuals who ordered the prints rather than the subjects. What is going on in these photographs? Historians of visual culture will undoubtedly be able to offer insights based on the images’ composition, the beguiling interplay of light and shadow, as well as the purposeful use of props and scenery, placing these images among Arapoff's finest work. Much, however, can be learned by situating the photographs in the context of his life in Oxford between 1933 and 1939. This endeavor illuminates further aspects of how the city's vibrant university culture facilitated expressions of queer identities and behaviors even as the darkening international socio-political situation and pathologized concepts of “homosexuality” were driving Oxford's gay students ever further into the shadows.

Born Kyril Semeonovitch Arapov in Warsaw on 21 October 1898, Arapoff, his mother, and his brother Peter fled Russia in 1919, the family having Tsarist connections.Footnote 67 Peter returned to Russia, where he championed the Eurasian movement (he was killed by the Bolsheviks in 1938). After a period in Paris, where he mixed with Jean Cocteau's coterie, Cyril (he anglicized his name when resident in Britain) moved to Germany, where he studied photography at the Dortmund studio of the renowned portrait photographer Annelise Kretschmer, one of the few female photographers to have her own studio at the time.Footnote 68

Figure 3 Images from the Arapoff collection. © Images & Voices, Oxfordshire County Council

Kretschmer's work is situated within Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity), a modernist art movement intimately associated with Weimar Germany, eschewing the romantic idealism of expressionism and seeking instead a practical engagement with the world in the here-and-now.Footnote 69 A number of artists associated with New Objectivity (including the Austrian theater and film director Georg Wilhelm Pebst) embraced pertinent social issues such as prostitution and homosexuality, representing such themes in a realistic, forthright manner without apologetics or overt emotionalism. The New Objectivity movement brought a down-to-earth, documentary quality to photographic portraits; Kretschmer's modernist portraits of women helped create the image of the neue Frau (New Woman) in Weimar Germany. At this time, Arapoff also knew Albert Renger-Patzsch, another leading proponent of New Objectivity in photography.Footnote 70

In 1933, Arapoff and his mother moved to 3 Church Street (now St. Andrew's Road) in the Oxford suburb of Headington. This was the home of fellow Russian émigrés Captain Vadim Narishkin, lecturer in French at Brasenose College, and his family. Arapoff's mother was governess to the Narishkin children. Arapoff, fluent in several languages, may initially have tutored, but his considerable talent with a camera quickly earned him a reputation as Oxford's leading portrait photographer. He moved to larger premises in Headington, establishing a studio at 19 Manor Road (now 41 Osler Road), where he worked fulfilling local commissions and providing images for national publications, including Geographical Magazine and major photography journals of the day, work that took him across the country and abroad. Today, Arapoff is best remembered for his pioneering documentary photography, especially of London's slums in the 1930s. At some point, he established a studio with photographer Elizabeth Frank in Oxford's city center at 119 High Street, until September 1941. He regularly exhibited in Oxford and London, earning critical acclaim. His distinctive style and range made him especially popular among Oxford's undergraduates, one commentator for the Cherwell (1 June 1935) stating that Arapoff's photographs “are rightly regarded as the most artistic camera work seen in Oxford of recent years.”Footnote 71

At the outbreak of war, Arapoff joined the Strand Film Company, first as a photographer, then as an assistant cameraman. With the shift to documentary film, he moved to London. In 1942, he joined the Crown Film Unit and made several important wartime documentaries. After the war, he worked on many films for leading documentary filmmakers of the postwar era, including Paul Rotha, Films of Fact, and Group 3. In 1961, he joined the National Coal Board Film Unit, until his sudden death on 14 October 1976. He is buried in an unmarked grave in London's Hampstead Cemetery. Arapoff never married or had children, and there are no textual sources, other than his photographs, that give any indication of his sexuality. However, Mike Seaborne, who, in his capacity as assistant keeper of the photographic collections at the Museum of London, wrote a short biography of Arapoff for the British Journal of Photography in 1980 and another for the introduction to Cyril Arapoff: London in the Thirties (1988), has related to me that Arapoff was homosexual and that this was known to those around him.Footnote 72

An insightful piece penned by Arapoff for the photography annual Modern Photography for 1935–36 testifies to his creative spirit, his willingness to work counter to the crowd, and his desire to change “the taste and understanding of the public.” He wrote, “My aims from the very beginning were to express the chief characteristic of a scene (whatever it was) or to render the real character of a person in [the] case of a portrait (which is so seldom done). Photography interests me only as a means of artistic expression, without which it sinks to a level of purely commercial and topical records.”Footnote 73 Arapoff's crusading social agenda for his art form is apparent across the broad range of his work. Although he took many photographs for commercial purposes, it is his images of the everyday life of social outcasts and their physical environment—London's slums, street markets, refugees—that are now recognized as his greatest contribution to photography. To this end, his use of the Rolleiflex 4 x 4cm, unusual at the time for a professional photographer, is significant, given his grounding in the principles of New Objectivity. The camera is portable and quick to use, enabling Arapoff to capture subjects swiftly, often unawares, minimizing the psychological trappings of formal posing.

Collections of Arapoff's photographs can be found in multiple archives, including the Museum of London, the Canal and River Trust, and Glasgow University. A private collection is also held in London by the eminent Russian Galitzine family, members of which Arapoff knew. A collection of portraits deposited at the National Portrait Gallery, produced during his residency in Oxford, depict leading actors of the day, all involved with the Oxford University Dramatic Society.Footnote 74 Notably, most of the male subjects are known to have been homosexual or bisexual. They include John Gielgud, Peter Glenville, and Glen Byam Shaw. There are portraits of the literary scholar Nevill Coghill, a major force behind the society from the mid-1930s, and the leading stars of the Markova-Dolin Ballet, Anton Dolin (the stage name of Patrick Kay) and Alicia Markova. There are also shots of Vivian Leigh, who appeared in the society's 1936 production of Richard II (co-directed by Gielgud and Byam Shaw), and Margaret Rawlings, who began her acting career while studying at Lady Margaret Hall (prior to this, she attended Oxford High School) and played Lady Macbeth with the society in 1937.

By far the largest collection of Arapoff's images, more than four thousand photographic prints and negatives, is housed at Oxfordshire History Centre.Footnote 75 The images depict a wide range of subjects, reflecting Arapoff's diverse interests and professional activities in Oxford through the 1930s. There are numerous portraits, particularly of children. Some sets constitute commissions for Oxford University Press and the Turl Street tailors Walters of Oxford. College scenes, ever popular, may have been produced for commercial purposes. A set marked “Sunday in Oxford” demonstrates Arapoff's exceptional talent for documenting everyday life. A particularly arresting series of images depicts Basque children, around four thousand of whom came to live at St. Joseph's, now Westfield House, in Aston, near Bampton in 1937 as refugees during the Spanish Civil War. Other sets depict theatrical productions at Oxford. Although most of these images relate to the productions, some are more intimate portraits of actors of the Oxford University Dramatic Society, possibly taken for use as publicity shots. Two images depict an unidentified young man in a suit, recognizable as Dennis Price, posing on a staircase (figure 4). Price came to Oxford with the stated aim of being ordained, but after becoming a member of the Buskins (Worcester College's drama society) and the society, he had a change of heart and decided to pursue an acting career. He left Oxford without taking a degree and enrolled at a London drama school. Correspondence concerning Price's exit from Worcester is preserved in the college's archives, the head of the college, Provost F. J. Lys, expressing regret (but not surprise) at Price's change of plans. Price left owing a significant debt to the college, and much of the correspondence concerns this. It was eventually settled by his father in 1938.

Figure 4 Young man, probably Dennis Price, photographed by Cyril Arapoff. © Images & Voices, Oxfordshire County Council.

Despite the diversity of subjects, no one viewing the large collection of Arapoff's Oxford photographs can fail to be struck by his images of handsome young men, some nude and seminude. While by no means pornographic, subjects pose for his camera in intimate and inviting postures. Sexual surrender and “visions of queer martyrdom” (to borrow Dominic Janes's phrase) pervade the images.Footnote 76 There are no comparable images of female subjects among Arapoff's extensive and diverse production; indeed, a gender skew is noticeable in his portraits generally. Images of male subjects (reflecting the male dominance of Oxford University, at least in part) predominate, and where female subjects are pictured, there is usually an absence of that intimate connection between photographer and subject that comes across so strikingly in many of Arapoff's portraits of male subjects.Footnote 77 Even his portraits of Vivien Leigh, well composed though they are, lack the intensity and eroticism of his portraits of young men. Arapoff himself betrays a gender bias in an insightful commentary in The Amateur Photographer and Cinematographer in June 1935. Outlining steps to producing a picture for exhibition, he wrote, “The most difficult subjects are of course grown-ups of a certain social standing, especially women, who in most cases remain self-conscious.”Footnote 78

Arapoff's images of nude and seminude young men most closely resonate with the amateur photographs of the architect Montague Glover, whose images of lissome young men provide a rare photographic document of a wealthy man's gay life in Britain through the middle decades of the twentieth century.Footnote 79 Harmonious with his other portraits, Arapoff's images differ in intent and composition from those of Glover. For example, Glover foregrounds the whole body of his subjects while, with some exceptions, few of Arapoff's subjects are depicted below the waist. There is an open and pulsating sexuality in Glover's images (ironically, all produced for private pleasure) that largely emanates from Glover himself; the homoeroticism of Arapoff's images (some of which may have been produced for one of his annual public exhibitions in Oxford) rests more intuitively, suggested sometimes by the positions of the subjects in relation to his camera but more often by their engagement with props—drapes, masks, a doll, spiritual iconography—indicating a subjective identification absent with Glover's young men.

The most striking and enlightening of Arapoff's studies of young men depicts a naked youth, head in arms, holding the base of an icon of Saint Sebastian (figure 5). By the 1930s, Saint Sebastian had long been appropriated as a representation of queer martyrdom.Footnote 80 Oscar Wilde used the name (“Sebastian Melmoth”) while in exile in Paris following his release from Reading Gaol in 1897. Many twentieth-century artists, writers, and poets—not least Waugh in Brideshead—utilized Sebastian's name, image, and story to convey the martyrdom of gay sexualities through eras of repression and persecution. Contemporaneously with Arapoff and Waugh, in 1934, the French modernist painter Albert Courmes produced a gay Sebastian partially attired in a French sailor's uniform; the American painter Marsden Hartley produced another in 1939.Footnote 81

Figure 5 Arapoff study of naked youth, head in arms, with an icon of Saint Sebastian. © Images & Voices, Oxfordshire County Council.

In the absence of substantial supplementary sources directly relating to the images, the identities of many of Arapoff's young male subjects are unknown. Feasibly, some are working-class youths whom Arapoff paid to pose for his camera. Such a scenario would not be beyond the bounds of possibility for the period, but it fails to account for the expressively queer content of the images and does not fit with Arapoff's bohemian and matter-of-fact documentary approach to photography. It is likely that some, if not most, of his homoerotic images feature young student actors of the Oxford University Dramatic Society. The heavy presence of student drama productions and the society's actors elsewhere in the Oxfordshire History Centre's collection of Arapoff's images, as well as in the National Portrait Gallery photographs, suggests as much. Moreover, some of the subjects interact dramatically with masks and other icons, conceivably theatrical props and scenery gleaned from university productions.

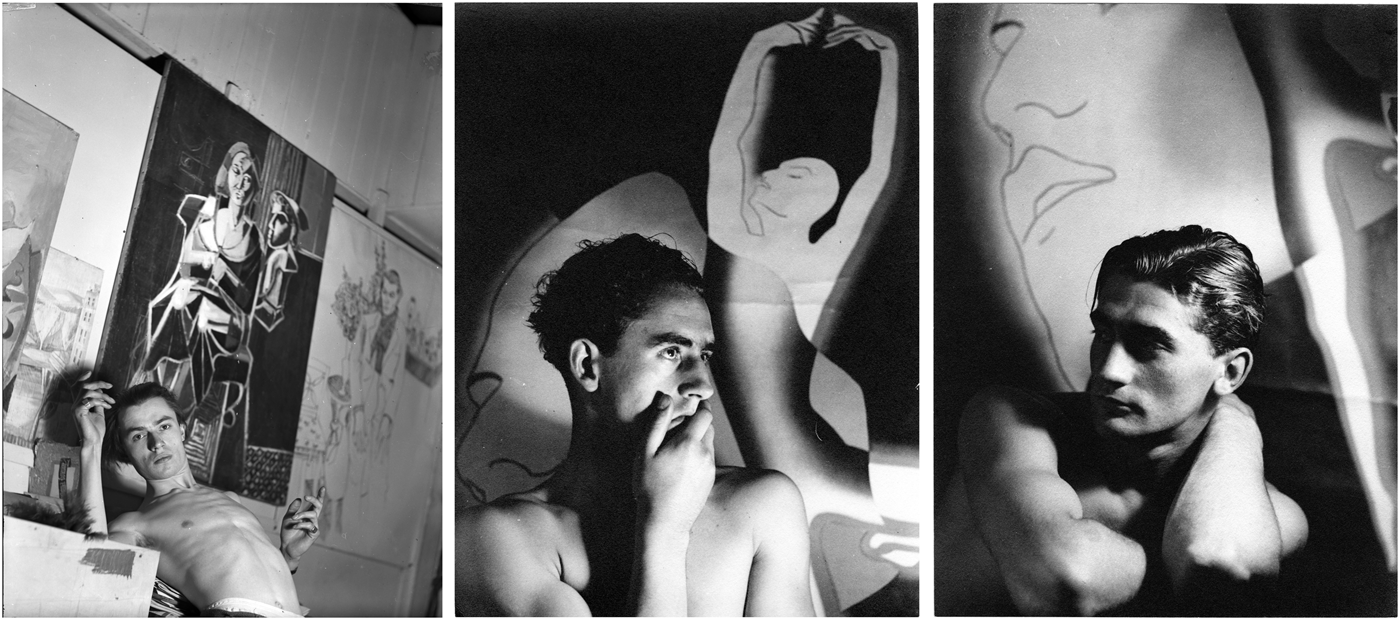

The intimate circle of young student actors and their acquaintances (such as Gielgud) was not the only source of creative inspiration, and responsive subjects, that Arapoff was able to engage with during his time in Oxford. His photographs and some supporting textual evidence demonstrate a comparable affinity for ballet and (mainly male) ballet dancers. Oxford was a major center in Britain's interwar dance scene, and the pages of the Isis and the Cherwell evidence the enthusiasm with which ballet productions and dancers were received in the city. Arapoff took numerous photographs of dancers. The Arapoff collection at Oxfordshire History Centre contains images of Ballets Russes and the Schwezoff School of Dancing (including a portrait of the eminent Russian dancer and choreographer Igor Schwezoff). Two more images show men posing in front of a famous poster, originally produced in 1935, by the French artist Paul Colin and featuring Serge Lifar, one of the twentieth century's greatest ballet dancers. Another image, depicting a shirtless young man leaning back in a provocatively inviting pose, his arms and hands bordering the picture hanging above him, has a similar dance aesthetic. Annotations suggest that this photograph and (by association) the previous two were taken for Picture Post but never published; perhaps Arapoff underestimated the conservatism of the British press. The subjects in these three images (figure 6) are older than the youths in other of Arapoff's nude and seminude studies and have discernibly greater muscle definition. They are likely professional dancers.

Figure 6 Photographs by Cyril Arapoff. © Images & Voices, Oxfordshire County Council

A sizable scholarship now penetrates the complex homoerotics of twentieth-century ballet.Footnote 82 The gay affairs of the great impresario Sergei Diaghilev, for example, are relatively well documented. In a remarkable series of nude studies, Arapoff captures something of the queer offstage life and artistry of Anton Dolin, proffering a very different aspect of Dolin's life than that portrayed in the formal portraits of Dolin and Markova now housed in the National Portrait Gallery. Annotations indicate that the photographs were taken at Dolin's London studio. The shots display an unmistakable dance aesthetic, but also a queer aesthetic that is produced in several ways. Not only is Dolin naked, and posing for a male photographer who was taking images with a queer sensibility elsewhere around the same time, but Dolin's graceful postures, posed pliantly on the studio floor and on a sofa, suggest sexual receptivity, or at least a sexual awareness, that eschews the classical balletic masculinity he performed on stage. (Dolin, who was Diaghilev's lover for a short time and a close friend of Vaslav Nijinsky, was a staunch defender of the onstage heteronormative gender conventions of classical ballet as an art form.Footnote 83) In one shot, he looks up from an exposed position on the floor, not at the camera or photographer but in a manner suggesting the presence of a dominant partner. Another highly suggestive image, apparently depicting Dolin (certainly demonstrating a similar dance aesthetic) moving his legs apart (figure 7), is solarized, a technique many photographers of the day used to create special effects. Arapoff appears to be using the technique (which involves briefly exposing the developing negative to light) to push the parameters of explicitness. Factoring in what is known of Dolin's sexuality, and that these photographs can only have been willingly produced for private use for personal and creative reasons, the images are an extraordinary record of the queer offstage life of Dolin's artistic world, documented by Arapoff with aplomb.

Figure 7 Anton Dolin photographed by Cyril Arapoff. © Images & Voices, Oxfordshire County Council.

Although the images of Dolin were taken in London, the close association of Oxford with Dolin's private life, and thereby the broad reach of queer artistic circles across localities in interwar Britain already indicated by Gielgud's involvement with the Oxford University Dramatic Society, is suggested by published remarks made by the ballet critic Richard Buckle, who referred to Arapoff on several occasions in his various memoirs. Buckle's comments offer rare insights into Arapoff's character, his life in Oxford, and his passion for the arts. In The Adventures of a Ballet Critic (1953), Buckle wrote that they met when Arapoff was photographing the society's 1935 production of Hamlet, directed by Nevill Coghill and featuring Peter Glenville in the title role. Buckle, then an undergraduate at Balliol College, designed the scenery and costumes. Arapoff and Buckle became friends, each sharing a genuine interest in the art of the other. Buckle wrote, “It was he who taught me something about tones, composition and cutting.”Footnote 84 Buckle used a number of Arapoff's photographs in early issues of his magazine Ballet, founded in 1939. Despite this fellow feeling, Buckle wrote of Arapoff that “dancing was too ready-made a subject for his independent spirit” and that he was “happier taking children, street-scenes and mountain landscapes.”Footnote 85 Still, in a later autobiographical volume, In the Wake of Diaghilev (1982), Buckle indicates that Arapoff was on intimate terms with the ballet crowd, introducing Buckle to Dolin and entertaining both at the Narishkin home.Footnote 86 Buckle's comments, all too brief in the context of his memoir, offer insight into Arapoff's life in Oxford and the circle of gay artists with whom he mixed and are worth reproducing in full:

After my first term at Balliol (during winter 1934–5) I was spending the vacation with my grandparents at Iffley outside Oxford. It was then that I met my first dancer. Living in Oxford was a White Russian photographer, Cyril Arapoff, whom I had run into and made friends with at an exhibition of his work at Ryman's gallery in the High. He was the first real “bohemian” I ever got to know. He had no sense of money or time, was often drunk and often in despair: but Cyril was a true artist. He taught me to look at photography with a more discerning eye and we got on like a house on fire. It was he who told me that Anton Dolin, whom Diaghilev had loved briefly and made his principal dancer in 1924, was appearing in a revue called King Folly at the New Theatre, and he took me round in the interval to meet him. Pat Dolin was glad to have an enthusiastic young undergraduate to talk to and I was thrilled by his rendering of a dance to Ravel's nightmare “Bolero”—an endurance test at least. He was returning to London that night—in a huge cream-coloured car borrowed from Lillian Harvey, star of the film Congress Dances—and we went first to drink coffee with the Narishkines at Headington. Then, instead of dropping me at my grandparents’ house at Iffley, as had been planned, Dolin swept me up to London, where I was obliged to stay the night at the slightly raffish Mount Royal hotel, since demolished, near Marble Arch. On my return to Oxford by train next morning, I found my grandmother in a terrible state, and my grandfather, who had informed the police of my disappearance, standing angrily on the doorstep.Footnote 87

An earlier rendering of the story (in The Adventures of a Ballet Critic) is shorter but adds that after their night together, Dolin (“my kidnapper”) gave Buckle, who had no money on him, five bob to make his own way back to Oxford.Footnote 88 The anecdote underscores the ease with which an older man (albeit, as with Gielgud, a celebrity) could pick up an enthusiastic young male Oxford undergraduate and, conversely, the ease with which a queer young Oxford student could visit London, by car or train, for some fun.Footnote 89

Other Arapoff images show a young man diving naked into a river from a high platform; one particularly impressive shot is taken from atop the board looking down on the diver captured in mid-air (see figure 8). A suggestive scenario is depicted in another set of shots showing a young man (possibly the diver) swimming in the river, climbing the bathing ladder, and pausing to peruse the scene on the grass bank; in another shot, the man, fully clothed, is pictured punting on the river. The location is readily identifiable from the wooden structures and landscape as Oxford's infamous Parson's Pleasure, an area on the bank of the Cherwell to the southeast corner of University Parks, cordoned off for male nude bathing at least since the nineteenth century. The young man is pictured apparently perusing—cruising—other naked men at the enclosed facility.

Figure 8 Photographs taken at Parson's Pleasure by Cyril Arapoff. © Images & Voices, Oxfordshire County Council.

Arapoff's images of nude male diving and bathing at the location, which he presumably took while naked himself, are typical of his down-to-earth, documentary approach to photography and resonate with other images by diverse artists who created erotically charged depictions of naked young men at bathing spots. Through the later decades of the nineteenth century and for much of the twentieth when homosexual acts between males were criminalized in Britain, male nudity and open-air bathing were closely associated with modernist notions of classical beauty and afforded opportunities for gay and bisexual men to meet, or simply look at male bodies, in a moderately safe environment. In London, as Houlbrook has described, indoor baths and outdoor bathing spots (such as the Serpentine, Hampstead Ponds, and Victoria Park) were enclaves of “homosexual rendezvous.”Footnote 90 Historians of the visual arts have long recognized that outdoor bathing provided several modernist artists, poets, and photographers with a pretext to depict naked youths, even with explicitly homoerotic motifs, with relative impunity. The French painter Frédéric Bazille produced several striking works in this vein: Le pêcheur à l’épervier, or Le pêcheur au filet (1868) and Scène d’été (1869). Young, lithe male nudes, often depicted swimming, sunbathing, or fishing, are the main subjects of the English painter and photographer Henry Scott Tuke.Footnote 91 Significant works on the theme by other British artists, many long since embraced with gusto by gay art collectors (who continue to drive prices today), were also produced by Duncan Grant, William Bruce Ellis Ranken, and Robert Sivell, to name a few.Footnote 92

Contemporaneously with Arapoff, the German photographer Herbert List took homoerotic photographs of young men at bathing spots.Footnote 93 Similarly, the English artist Keith Vaughan photographed young men at Highgate Ponds in 1933 and at Pagham Beach in West Sussex between 1935 and 1939; the images were important for Vaughan's trajectory as an artist and provided source material for his later drawings and paintings.Footnote 94 Several of Montague Glover's photographs were taken at London's bathing spots where he photographed young working-class men relaxing together.Footnote 95 He photographed them with sexual intent; his desire for his subjects form the premise of the images. In contrast, Arapoff seeks only to document the activities of his subject(s) at Parson's Pleasure—punting, diving, swimming, and cruising—very much as he documents elsewhere other aspects of daily life in Oxford.

By the time Parson's Pleasure was closed in 1991, it was well known as a gay cruising site, but how this use of the facility developed over time is difficult to assess. There are indications that at least by the 1920s some men used Oxford's several male-only bathing areas to watch and potentially pick up youths, although the sparse references may reflect longer-standing practices. Michael Davidson, a self-professed “lover of boys,” spent a short period in the city working for the Clarendon Press (Oxford University Press) in 1927.Footnote 96 During the summer, he frequented Long Bridges, a public bathing spot on a backwater of the Isis to the south of the city, accessible along the towpath from Folly Bridge and, later, Donnington Bridge. Recalling his experiences in 1962, Davidson described how he watched adolescent boys alongside Robert Dundas, the “massive and renowned” tutor and censor of Christ Church, who “lay on the grass like a contemplative walrus and appraised the scampering urchins around him.”Footnote 97 Davidson described how Dundas presented local authorities with gymnastic equipment for the area, at least a set of parallel bars, solely for the purpose of further gratifying his pedophilic or ephebophilic leering. For his part, Davidson took photographs at Long Bridges using a camera devised to look like it was pointing in one direction while taking furtive images in another. Dundas was displeased with this activity, as well as any overt sexual activity at Long Bridges, as he feared it would provoke the local council into ending the tradition of nude male bathing in the area in favor of mixed, costumed bathing. According to Davidson, this had happened by the time he revisited Oxford in 1941, allegedly because local retailors put pressure on the local council in an effort to sell more bathing costumes. More associated with “gown” rather than “town,” Parson's Pleasure appears to have avoided the shadow of pedophilia or ephebophilia that Davidson's memoir indicates was present at Long Bridges, a situation that may have been aided by the creation of a separate area, Dame's Delight, set aside for women and children between 1934 and 1970.Footnote 98 Parson's Pleasure was never converted to mixed-sex or costumed bathing.

Other indications that Oxford's long-standing tradition of male-only skinny dipping became associated with sexual impropriety during the interwar period can be found in the Cherwell and the Isis. The Cherwell of 10 June 1933 contains a cartoon that indicates that the homoerotic potential of Oxford's male-only bathing spots, specifically Parson's Pleasure, was increasingly the object of suspicion and jocularity (and, potentially, private curiosity). The image, titled “P. P.” (that is, Parson's Pleasure), shows two men smoking and engrossed in conversation at a dining table. One of them says, “I don't see where the pleasure comes in.”Footnote 99 Taken in isolation, the joke is not now immediately apparent; the cartoon, in fact, is part of a series that featured irregularly in the Cherwell from February to June 1933, precisely when Richard Rumbold and his novel Little Victims were the objects of merciless ridicule throughout Oxford. The cartoons form part of the Cherwell's concerted attack on the book and its author. All the cartoons use the same image of the men talking; only the title and the remark change. The unstated premise—the joke—is that the two men are talking about homosexuality. Other examples of title and remark are: “ANCIENT HISTORY” / “But take Alcibiades” (11 February); “SHALL I COMPARE THEE . . . ” / “But it's apparent from the Sonnets” (4 March); SHADES OF THE PRISON HOUSE / “I'd sooner go to Reading goal [sic]” (11 March); COMRADES IN DISTRESS / “Crichton evidently doesn't like women either” (29 April); BIOLOGY / “Anyway, worms do” (13 May); and SOLITUDE / “Alas! The Church claimed him . . . ” (27 May).Footnote 100 The inclusion of a jibe about Parson's Pleasure in the series is therefore a purposeful expression that the bathing spot was perceived, at least potentially, as a site of sexual transgression.

The Isis of 8 June 1938 includes a two-page bespoke advertisement for Hercules Cycle & Motor Co. Ltd. of Birmingham titled “Road v River Rivalry . . !” The ad venerates the newly established Oxford University Cycling Club, placing it in rivalry with the Oxford University Boat Club. Significantly, it is founded on a heteronormative motif: a young woman (“Emily”), pictured centrally in a bathing suit, has supposedly dumped “Claude the oarsman” for “Clarence the cyclist.” One of the cameos depicts a boat on a river with one young man rowing fully clothed and another bare-chested (he is visible only above the waist). Two other young men swim naked in the water. Two cyclists ride past; one of them says, “This river is a sink of iniquity Bellamy. I've a mind to tell my tutor about it.” The other cyclist responds: “I too! Supposing I had been riding out with my own dear little Emily such a scene might have prostrated her.” A policeman watching the scene says, “If I ’ad my way I'd lock up the ole lot of ’em.” A caption states: “While none of these swimmers is anatomically indiscreet, the effect on any member of the fairer sex who should chance to be passing can be left to the imagination. Do you wonder that Cecil and Bill Bellamy are seething with righteous indignation?”Footnote 101 The whole piece is, of course, meant to be amusing but the assertion that the scene of nude male bathing is “a sink of iniquity” and a cause of concern to the authorities, gown and town, appears to go beyond the apparent concern for female modesty. This is a change from earlier attitudes toward male nude bathing in Oxford, a tradition that some of Oxford's most eminent dons (such as C. S. Lewis) had long revered and enjoyed with no suggestion of moral reprobation. Possibly the activities of Davidson and Dundas, and perhaps other pedophiles, or the emergence of a more egalitarian mode of gay cruising among Oxford's male students, were changing perceptions of Oxford's male-only bathing areas (Davidson's activities resulted in his ejection from Hyde Park in 1922).Footnote 102 But significant also is the increasing, if often begrudging, acceptance of young female students (“undergraduettes”) at Oxford and a discernible shift in the culture of the university toward a modernist heteronormativity largely absent in Oxford prior to the 1930s. Dame's Delight may have accommodated the physicality of the new sexual politics of bathing at Oxford at least temporarily, but the increasing presence of “undergraduettes” in the city, highly sexualized in Oxford's print culture, irrevocably changed perceptions of what it meant for Oxford's male dons and students to relax and bathe naked together.