Introduction

In the process of professionalizing family firms (FFs), the decision to appoint or replace a chief executive officer (CEO) is one of the most critical and far-reaching corporate decisions, with significant implications for long-term firm performance (Calabrò, Minichilli, Amore & Brogi, Reference Calabrò, Minichilli, Amore and Brogi2018; Cirillo, Romano & Pennacchio, Reference Cirillo, Romano and Pennacchio2015; Deng & Liu, Reference Deng and Liu2024; Luan, Chen, Huang & Wang, Reference Luan, Chen, Huang and Wang2018; van Helvert-beugels, Nordqvist & Flören, Reference van Helvert-beugels, Nordqvist and Flören2020; Visintin, Pittino & Minichilli, Reference Visintin, Pittino and Minichilli2017; Waldkirch, Nordqvist & Melin, Reference Waldkirch, Nordqvist and Melin2018). While FFs often prefer to appoint family members as CEOs due to their desire for control and involvement (Aparicio, Basco, Iturralde & Maseda, Reference Aparicio, Basco, Iturralde and Maseda2017; Berrone, Cruz & Gomez-Mejia, Reference Berrone, Cruz and Gomez-Mejia2012; Gomez-Mejia, Cruz, Berrone & De Castro, Reference Gomez-Mejia, Cruz, Berrone and De Castro2011; Miller, Le Breton-Miller & Lester, Reference Miller, Le Breton-Miller and Lester2011, Reference Miller, Breton-Miller and Lester2013), this is not always feasible. The limited availability of capable and willing family members may compel FFs to appoint non-family CEOs (NF-CEOs) (Tabor, Chrisman, Madison & Vardaman, Reference Tabor, Chrisman, Madison and Vardaman2018). The above literature acknowledges that this may occur, for example, when the firm requires leadership skills that surpass those available within the family, or when the designated family leader lacks the interest or readiness to assume the role. Additionally, the absence of a successor or the unpreparedness of potential successors can also necessitate the appointment of an NF-CEO (De Massis, Chua & Chrisman, Reference De Massis, Chua and Chrisman2008; Waldkirch et al., Reference Waldkirch, Nordqvist and Melin2018).

The recruitment of NF-CEOs in FFs does not always lead to successful outcomes (Chrisman, Memili & Misra, Reference Chrisman, Memili and Misra2014). The benefits and challenges associated with employing NF-CEOs – and non-family managers more broadly—have been extensively reviewed in recent years (Hiebl & Li, Reference Hiebl and Li2020; Tabor et al., Reference Tabor, Chrisman, Madison and Vardaman2018; Waldkirch, Reference Waldkirch2020). Scholars have contributed to this growing body of research by exploring both professional and psychological dimensions of NF-CEO appointments through diverse theoretical lenses. These include socioemotional wealth (SEW) theory (Berrone et al., Reference Berrone, Cruz and Gomez-Mejia2012; Gómez-Mejía, Haynes, Núñez-Nickel, Jacobson & Moyano-Fuentes, Reference Gómez-Mejía, Haynes, Núñez-Nickel, Jacobson and Moyano-Fuentes2007), agency theory (Cruz, Gómez-Mejia & Becerra, Reference Cruz, Gómez-Mejia and Becerra2010; Schulze, Lubatkin, Dino & Buchholtz, Reference Schulze, Lubatkin, Dino and Buchholtz2001), psychological ownership (Huybrechts, Voordeckers & Lybaert, Reference Huybrechts, Voordeckers and Lybaert2013), stewardship theory (Blumentritt, Keyt & Astrachan, Reference Blumentritt, Keyt and Astrachan2007; Y.-M. Chen, Liu, Yang & Chen, Reference Chen, Liu, Yang and Chen2016; Miller & Le Breton-Miller, Reference Miller and Le Breton-Miller2005), upper echelons theory (D’Allura, Reference D’Allura2019; Skorodziyevskiy, Chandler, Chrisman, Daspit & Petrenko, Reference Skorodziyevskiy, Chandler, Chrisman, Daspit and Petrenko2024; Wong & Chen, Reference Wong and Chen2018), social exchange theory (Waldkirch et al., Reference Waldkirch, Nordqvist and Melin2018), and cultural competence (Blumentritt et al., Reference Blumentritt, Keyt and Astrachan2007; Hall & Nordqvist, Reference Hall and Nordqvist2008), among others.

However, the existing literature provides only partial explanations for the success or failure of non-family NF-CEOs on FFs. Several scholars have acknowledged persistent research gaps and theoretical inconsistencies that contribute to divergent interpretations of NF-CEO outcomes (Skorodziyevskiy et al., Reference Skorodziyevskiy, Chandler, Chrisman, Daspit and Petrenko2024; Tabor et al., Reference Tabor, Chrisman, Madison and Vardaman2018; Waldkirch, Reference Waldkirch2020). For example, while some studies suggest that altruistic motivations may drive non-family managers to join FFs (Bernhard & O’Driscoll, Reference Bernhard and O’Driscoll2011), others emphasize agency-related concerns, including the risk of a reduced candidate pool due to perceived conflicts of interest or limited autonomy (Chrisman et al., Reference Chrisman, Memili and Misra2014). These mixed findings underscore the need for further research to identify the key factors that contribute to successful NF-CEO appointments.

Moreover, the appointment of NF-CEOs has become increasingly common over the past decade, reflecting a broader shift toward professionalization and modernization in family-owned businesses (PWC, 2025). Yet, despite this trend, challenges remain. Recent research on Taiwanese FFs found that NF-CEOs faced significantly higher dismissal rates than family CEOs (Shen, Gu (Cecilia), & Lu, Reference Shen, Gu (Cecilia) and Lu2024). This discrepancy further highlights the complexity of managing NF-CEO appointments and the importance of aligning leadership choices with family expectations and firm dynamics.

While several studies have examined NF-CEOs in FFs, many of them have focused on firms listed on stock exchanges or those with ownership stakes held by external (non-family) investors. However, the heterogeneity of FFs (Cheng, Cummins & Lin, Reference Cheng, Cummins and Lin2017; Tabor et al., Reference Tabor, Chrisman, Madison and Vardaman2018; Waldkirch, Reference Waldkirch2020) has led scholars to call for more research specifically targeting POFFs to better understand the unique challenges and opportunities associated with employing NF-CEOs in these contexts. Such research can help clarify the complex factors that influence how well a CEO’s profile aligns with the specific needs of these firms.

To deepen understanding of this subject, both (Tabor et al., Reference Tabor, Chrisman, Madison and Vardaman2018) and (Hiebl & Li, Reference Hiebl and Li2020) recommend conducting qualitative research, which can yield insights not readily captured through quantitative measures. In line with this recommendation, we adopt flexible pattern matching as a qualitative research tool particularly well-suited for exploration and theory development (Bouncken, Ratzmann & Kraus, Reference Bouncken, Ratzmann and Kraus2021). This method builds on existing theoretical approaches(Cecilia), while also enabling the empirical analysis necessary to refine and expand existing theories (N. Sinkovics, Reference Sinkovics, Cassell, Cunliffe and Grandy2018; R. R. Sinkovics, Penz & Ghauri, Reference Sinkovics, Penz and Ghauri2008).

This article applies this method to the analysis of seven case studies of POFFs located in Spain, each with varying experiences in employing NF-CEOs. Drawing on qualitative micro-level data collected through interviews with both family and non-family executives and CEOs, this article explores the particularities that appear to play a decisive role in the success of NF-CEOs in POFFs. The analysis is informed by theoretical perspectives that highlight the specificity of human capital in FFs and the heterogeneity of workers.

This article advances the understanding of why some NF-CEOs in POFFs succeed—where success is defined as whether the non-family CEO fulfils the expectations of the owner family—while others do not. It reveals that success depends, in part, on the NF-CEO’s specific investment in understanding the owning family, which, in turn, requires longer minimum tenures to become effective. The study highlights the importance of aligning the career life cycles of NF-CEOs with those of potential family successors, identifying this alignment as a critical condition for successful appointments. It also shows that a cooperative and long-term-oriented personality is essential for NF-CEOs to integrate effectively within the context of family businesses. Moreover, as far as we know, this is the first study to apply the theory of specific human capital to the context of NF-CEOs, enriching it with insights from the perspective of human resource heterogeneity. By combining these theoretical lenses, the article not only provides a foundation for future research but also opens new directions for examining the dynamics of NF-CEO tenures in POFFs.

The structure of this article is as follows: Section 2 contains the literature review, Section 3 introduces the dataknow and the methodology used, Section 4 presents the results, Section 5 includes a discussion of these results, and Section 6 concludes.

Literature review

Socioemotional wealth (SEW) and NF-CEOs

Primary sources characterizing FFs are the family-centered, non-economic goals these firms pursue, and the SEW that the achievement of these goals produces (Chua, Chrisman & De Massis, Reference Chua, Chrisman and De Massis2015). According to the SEW approach, family owners frame problems in terms of assessing how actions will affect socioemotional endowment (Chua et al., Reference Chua, Chrisman and De Massis2015; Gomez-Mejia et al., Reference Gomez-Mejia, Cruz, Berrone and De Castro2011).

Hiring an NF-CEO in a POFF can significantly influence the five dimensions of socioemotional wealth (SEW) identified by (Berrone et al., Reference Berrone, Cruz and Gomez-Mejia2012). First, control and influence of family members over strategic decisions often diminish when a non-family executive is brought in. While this may enhance managerial professionalism, it can also generate tension if family owners perceive a loss of authority (Gomez-Mejia et al., Reference Gomez-Mejia, Cruz, Berrone and De Castro2011). Second, identification of the family with the firm may weaken, as the firm’s public image and internal culture become more closely associated with the NF-CEO rather than the family legacy (Zellweger, Eddleston & Kellermanns, Reference Cruz, Gómez-Mejia and Becerra2010). Third, binding social ties, which refer to the emotional connections and trust between family and non-family members, may either strengthen or deteriorate. A well-integrated NF-CEO can foster inclusivity and broaden the organizational sense of belonging, but a misaligned leader may alienate long-standing employees and family stakeholders (Cruz et al., Reference Cruz, Gómez-Mejia and Becerra2010).

Fourth, the emotional attachment of the family to the firm can be strained if the NF-CEO pursues strategies that diverge from the founding vision or disrupt symbolic traditions. However, such changes may also professionalize the firm and ensure its long-term viability (Chua, Chrisman & Sharma, Reference Chua, Chrisman and Sharma2003). Lastly, the renewal of family bonds through dynastic succession can be delayed or reconsidered when an NF-CEO is in place. While this may allow for smoother transitions and better-prepared successors, it may also signal a shift away from intergenerational continuity (Le Breton–Miller, Miller & Steier, Reference Le Breton–Miller, Miller and Steier2004). Overall, the impact of hiring an NF-CEO depends largely on how well their leadership aligns with the family’s SEW priorities and their ability to integrate into the firm’s unique socioemotional basis.

Human capital specificity

Different perspectives on human capital have been employed in research on CEOs in FFs. For example, (Ahrens, Landmann & Woywode, Reference Ahrens, Landmann and Woywode2015) develop a ‘human capital score’ using proxy indicators such as general and industry-specific experience, as well as business education and skills, and show that FFs often prefer family successors, especially male. (Blanco-Mazagatos, de Quevedo-puente & Delgado-García, Reference Blanco-Mazagatos, de Quevedo-puente and Delgado-García2018) focus on human resource (HR) practices, including skill-enhancing mechanisms and motivational strategies, highlighting that later-generation FFs are more likely to adopt professional HR practices. (Llanos-Contreras, Baier-Fuentes & González-Serrano, Reference Llanos-Contreras, Baier-Fuentes and González-Serrano2022) analyse how SEW, family human capital, and family social capital influence organizational social capital in small family firms. The study highlights the central role of family involvement and informal structures, which can pose challenges for hiring non-family CEOs. Additionally, with a focus on NF-CEOs, (Waldkirch et al., Reference Waldkirch, Nordqvist and Melin2018) link the affective dimension of interpersonal relationships to NF-CEO retention and turnover.

Building on and extending these contributions, we adopt the classical definition of human capital theory proposed by (G. S. Becker, Reference Becker1964), which views individual workers as possessing a set of skills or abilities that can be improved or accumulated through education and on-the-job training—hereafter referred to as knowledge acquisition, in line with its primary purpose. According to this theory, worker productivity is directly related to the level of accumulated skills. Two forms of knowledge acquisition are distinguished: general and firm-specific. General knowledge acquisition enhances an individual’s productivity across multiple firms, including the one providing the training. In contrast, firm-specific knowledge acquisition increases productivity only within the current firm, offering no transferability to other organizations. It is widely accepted that new employees require an investment in firm-specific knowledge before reaching full productivity. Human capital theory suggests that such investments generate mutual incentives—through shared costs and benefits—for the employer and employee to maintain the employment relationship, thereby influencing the minimum efficient tenure (G. Becker, Reference Becker1975; Hashimoto, Reference Hashimoto1981).

(Madanoglu, Memili & De Massis, Reference Madanoglu, Memili and De Massis2020) point out that asset specificity in FFs is expected to be higher than in NFFs. This is largely due to the recognized influence of the owner family on the business, often exerted through a complex combination of economic, cultural, social, and emotional dimensions (Sharma, Reference Sharma2004). Such influence fosters the development of tacit and highly specific knowledge that is difficult to codify and transfer (Sirmon & Hitt, Reference Sirmon and Hitt2003). In POFFs, NF-CEOs must therefore invest in acquiring knowledge not only about the firm but also about the owning family. This dual investment increases the cost of adaptation and necessitates longer minimum tenures for NF-CEO contracts compared to those in NFFs, to justify the greater time required for integration.

However, achieving these longer tenures can be complicated by the life-cycle dynamics of both the NF-CEO and the family. For instance, if successors are nearing readiness to take over the business, NF-CEO candidates may hesitate to accept the position due to concerns over limited tenure (Cheng, Chen & Dai, Reference Cheng, Chen and Dai2013; Fang, Randolph, Memili & Jj, Reference Fang, Randolph, Memili and Jj2016; Sonfield & Lussier, Reference Sonfield and Lussier2009; Xu, Hitt & Dai, Reference Xu, Hitt and Dai2020). In such scenarios, the developmental stage of the successor influences the expectations and strategic role of the NF-CEO, particularly in firms that intend to pass ownership and control to the next generation. Conversely, we could argue that NF-CEO candidates approaching retirement may lack sufficient time to absorb the complex knowledge required for success in a POFF, thereby limiting their suitability for the role.

We could also anticipate that the required investment in firm-specific knowledge is likely lower when NF-CEOs are promoted internally. In these cases, the individual is already embedded within the firm—the firm-specific investment costs have already been borne—and may only require further development of general managerial competencies at the CEO level. Nonetheless, even internally promoted NF-CEOs may need to gain access to firm knowledge that is exclusive to top-level leadership, particularly concerning the family dimension and strategic vision.

Human capital heterogeneity

The compatibility between a non-family CEO (NF-CEO) and the family firm (FF) context is shaped by a multidimensional set of factors, including the executive’s personality traits, professional background, leadership style, and, crucially, their degree of familiarity with the owning family and its values. Beyond technical expertise or managerial acumen, relational and emotional intelligence appears pivotal in navigating the idiosyncrasies of family-owned firms (Hall & Nordqvist, Reference Hall and Nordqvist2008).

Such attributes may be particularly important in the context of POFFs, where the family’s identity is deeply embedded in the firm’s culture and decision-making processes. The ability of NF-CEOs to decode informal communication patterns, understand unspoken priorities, and adapt to a firm’s socio-emotional wealth (SEW) orientation can foster trust and facilitate alignment with both the family and the broader organization.

Furthermore, some authors (Dezsö & Ross, Reference Dezsö and Ross2012; Heyden, Fourné, Koene, Werkman & Ansari, Reference Heyden, Fourné, Koene, Werkman and Ansari2017) acknowledge the heterogeneity of the external managerial talent pool. Potential NF-CEOs differ not only in their technical qualifications but also in their cognitive styles, interpersonal capabilities, and time orientation. For example, executives who are long-term oriented, possess high levels of emotional intelligence, and exhibit a cooperative or stewardship-oriented disposition may be better aligned with the values and governance style of FFs.

This perspective challenges the assumption that all NF-CEOs approach FFs with the same motivations or expectations. Instead, it suggests that successful integration into a POFF requires a deliberate selection process—on both sides—that accounts for these deeper personality and relational characteristics. To our knowledge, the heterogeneity of the pool of NF-CEOs in terms of motivations and expectations has not yet been considered in the extant literature on FFs.

Methodology

Method selection: This article uses the flexible pattern matching approach. Flexible pattern matching is a qualitative research approach that involves the iterative matching between theoretical patterns derived from the literature and observed patterns emerging from the empirical data (N. Sinkovics, Reference Sinkovics, Cassell, Cunliffe and Grandy2018). The use of a priori patterns provides a rationale for data collection and analysis. At the same time, these a priori patterns can be reviewed and modified iteratively to allow for the exploration and emergence of new empirical patterns from the data (Bouncken et al., Reference Bouncken, Ratzmann and Kraus2021). The construction of this article is also phenomenon-driven: Its motivation originates from the growing importance of NF-CEOs in POFFs and the insufficient extant theory in the FF domain to explain the success and failure of employing these executives. Qualitative studies can provide insights that help explain underlying mechanisms and processes (Eisenhardt, Reference Eisenhardt1989; Muhic & Bengtsson, Reference Muhic and Bengtsson2021; Yin, Reference Yin2009).

The flexible pattern-matching approach can be superior to other qualitative research methods, like grounded theory, when research begins with a tentative theoretical framework but expects that empirical data may require its refinement. This approach allows theory to guide the research without constraining interpretation, making it ideal for dynamic and evolving phenomena (N. Sinkovics, Reference Sinkovics, Cassell, Cunliffe and Grandy2018; R. R. Sinkovics et al., Reference Sinkovics, Penz and Ghauri2008), as is the case with POFFs hiring NF-CEOs. It also preserves the contextual depth of qualitative inquiry while enabling structured comparisons across cases, offering a balance between interpretive richness and analytical clarity (Eisenhardt, Reference Eisenhardt1989). These strengths make flexible pattern-matching particularly suitable for studying complex social processes where both theory development and contextual sensitivity are essential.

Case selection: Multiple cases (7) with diverse profiles in terms of experiences in the employment of NF-CEOs were selected, aiming to produce replicated or alternative explanations concerning the employment of these executives. The sample included firms with successful experiences, firms with unsuccessful experiences, and firms with both. Using flexible pattern matching, seven cases can be considered a sufficient sample because the analysis is theory-informed, and the cases are purposefully selected and analysed in depth (N. Sinkovics, Reference Sinkovics, Cassell, Cunliffe and Grandy2018).

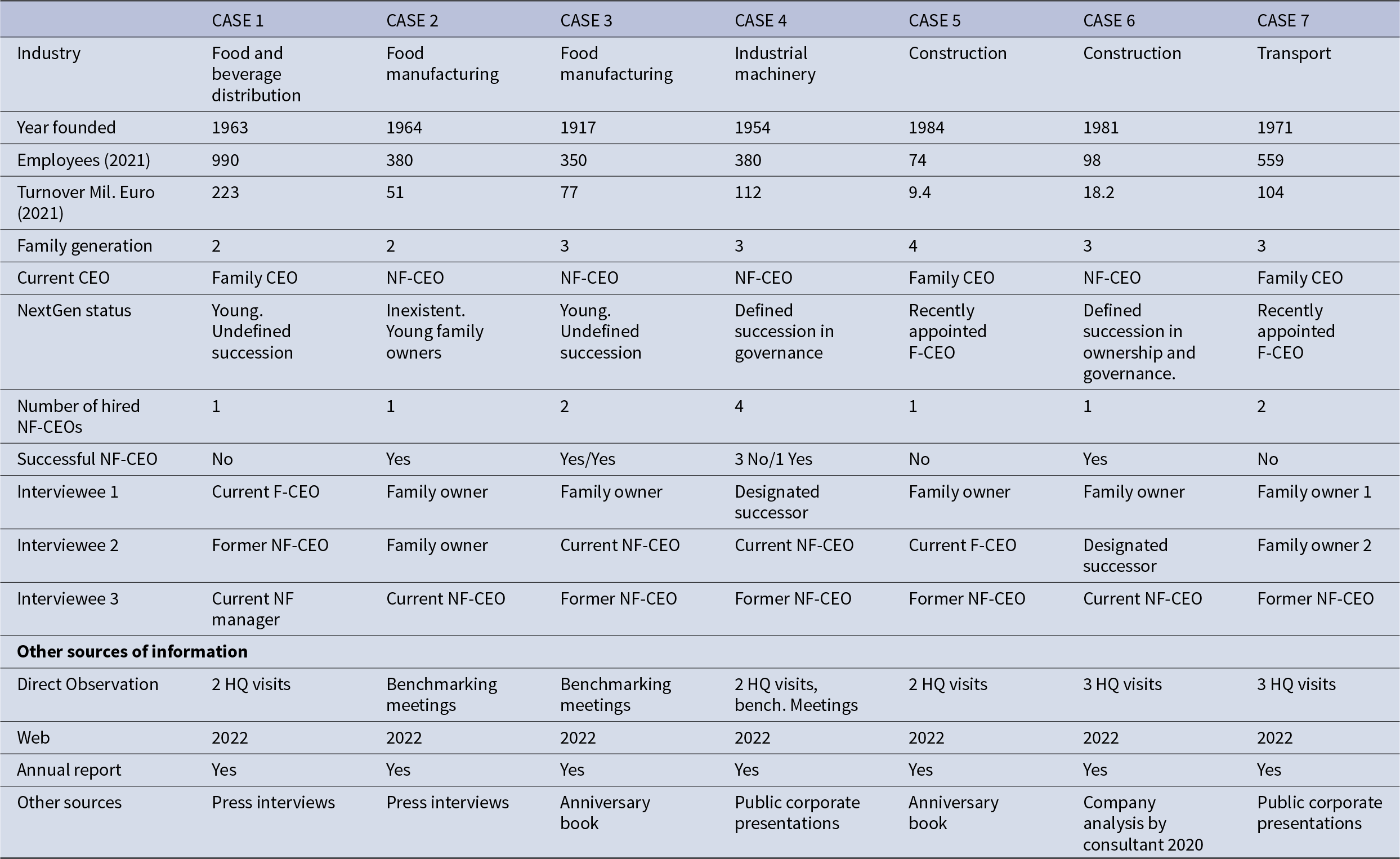

The firms selected were distributed across different economic activities, with four in manufacturing and three in services. They were all located in the north-east region of Spain (Catalonia). The selected firms were medium and large (European Union, 2020) and were privately owned by a family. Catalonia provides a particularly relevant context, given its significant contribution to Spain’s GDP. FFs—primarily POFFs—form the backbone of the Catalan economy, representing 89% of private enterprises, generating 57% of Gross Added Value, and accounting for 76% of private sector employment (Álvarez Gómez, Gallizo Larraz & Marquès Gou, Reference Álvarez Gómez, Gallizo Larraz and Marquès Gou2017). Table 1 contains the descriptive data of the seven firms studied.

Table 1. Description of family firms and interviewees

Note: F: Family, CEO: Chief Executive Officer, NF: Nonfamily, HQ: Headquarters.

Data collection and data analysis: The data were collected via in-depth face-to-face interviews to gain detailed accounts of the experiences under study. The minimum number of interviewees for each firm was two, one of whom was a leader from the owning family and the other the current or a former NF-CEO. Additional interviewees included other non-family managers, former NF-CEOs, and/or members of the younger generation of the owning family. Participants were interviewed separately over multiple visits to the firm premises. Each interview NF-CEOs,lasted between 1 and 2 hours. There were two experienced interviewers per interviewee, and interviews were recorded to enhance accuracy.

The interviews were conducted in three rounds between March 2021 and December 2021 to adapt the initial themes to the observed empirical patterns. The first round of interviews was directed at family owners, and the themes addressed were related to reasons for hiring (professionalization) and not hiring NF-CEOs (relating to the SEW dimensions). The interviewees were also asked about the success/failure of their firms’ experiences in hiring NF-CEOs and what they thought were the reasons for these successes/failures.

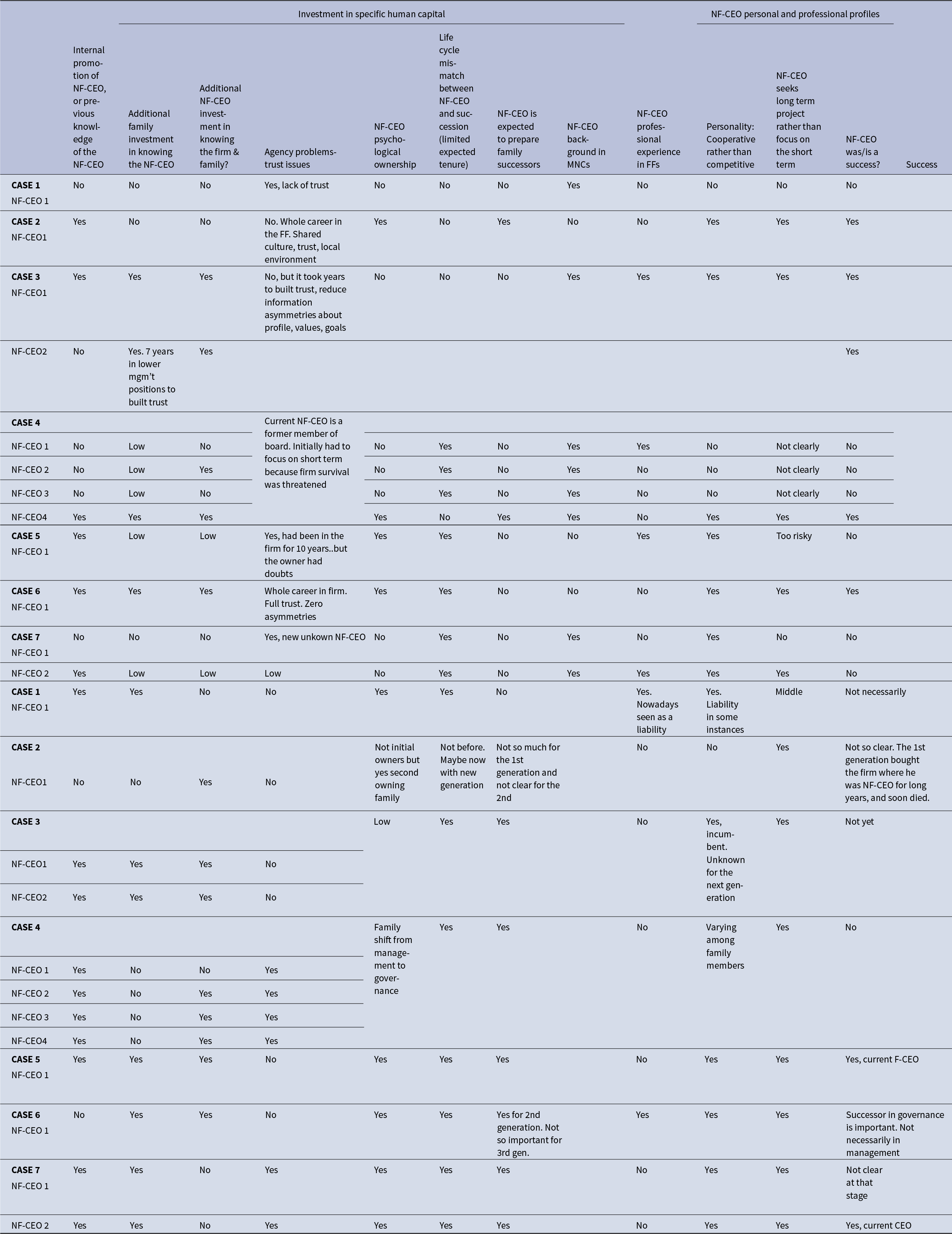

After the first round of interviews with FF owners, two researchers independently coded the interview transcriptions (Excel and NVivo R1 were used at this stage). Their initial coding schemes were then compared, discussed, and, with input from a third researcher, consensus was reached, resulting in an initial unified coding structure. As anticipated, the reasons why the firms hired NF-CEOs were related to professionalization and capacity issues (for instance, successors not being ready), while the reasons why the firms preferred not to hire NF-CEOs were related to some of the SEW dimensions. Besides the original themes considered, trust issues in corporate decision-making appeared as a main motive for firing an NF-CEO. Considering the gaps that emerged in the ongoing analysis, the original topics were reviewed and extended to cover risk-taking in strategic corporate decisions and life-cycle data. The questions asked in the second round of interviews covered both the initial and the added topics, this time addressed to the NF-CEOs. Subsequent coding and analysis of the transcribed conversations with the NF-CEOs brought to light the themes relating to their professional background and personal profile, adding accounts of the advantages and obstacles for NF-CEOs in terms of working in FFs, and of the fit of their profiles (heterogeneity of human capital) in this respect. A round of follow-up interviews with family owners took place to cover the themes added to the original list. Archival data (related press and online publications) were also used in some instances of the analysis. Table 2 presents a summary of the refined coding structure resulting from the iterative process of interviewing and coding.

Table 2. Data structure

Findings

Table 2 contains the coded data that arose from the transcribed interviews. The first column is related to professionalization and the reasons why POFFs hire NF-CEOs. The following columns contain data on the SEW dimensions of the POFFs, as proposed by (Berrone et al., Reference Berrone, Cruz and Gomez-Mejia2012), and are related to reasons why POFFs may prefer not to hire NF-CEOs. These columns are followed by others with information on investments in specific human capital and the professional and personal profiles of NF-CEOs. The last column signals whether the experience was successful or not.

Reasons for hiring and for not hiring an NF-CEO

Among the reasons for hiring NF-CEOs was the need to professionalize the management of the POFF when it grew and the owners’ lack of capability to continue managing it: ‘The firm hired its first NF-CEO seeking professionalisation,…, as my father lacked the capacity for managerial positions’ (Case 1, current F-CEO), and ‘We realised that there were many issues about which we had no knowledge, and that we needed qualified people inside the firm’ (Case 7, family owner 1, former F-CEO). Additional reasons were successors being too young: ‘When I joined the firm, the owner’s son and daughter were kids. So in this case family succession was not an option’ (Case 3, current NF-CEO); the family leader having other, sometime entrepreneurial, interests: ‘I wanted a change, to have time for me to rest, teach at the university, write a book… so I promoted the Head of the Sales Department to CEO’ (Case 5, family owner – former F-CEO); and the family being too complex to agree on a family CEO: ‘In the next 5 years, the 3rd generation will be managing the firm: 16 cousins…’ (Case 4, current NF-CEO).

However, when there are capable and willing candidates in the family, a family CEO tends to be preferred. For instance, an interviewee declared, that ‘the basic model is that the owner runs the firm. An NF-CEO is second best, for when no family member is available’ (Case 3, current NF-CEO). This preference can be related to the SEW dimension (1), control and influence of family members over strategic decisions ‘NF-CEOs must give explanations for the decisions they make. Strategic decisions must be agreed on’ (Case 3, current NF-CEO). A common managerial practice was family owners monitoring the NF-CEO closely and limiting their decision rights (‘…The family must feel consulted over these decisions,’ Case 4, designated successor). There was one case where these controls did not apply (‘Mine is a very unusual case…I had almost full decision rights and monitoring was very weak. The owner considered that he could no longer make decisions since he no longer knew the operations…’ (Case 2, current NF-CEO).

With regards to the SEW dimension (2), identification of the family with the firm, some relevant quotes were, for example: ‘For my dad, the firm is his life project’ (Case 2, family successor) and ‘I lived in a family where there wasn’t a lunch or dinner that we didn’t talk about the firm. My dad was from a generation for whom life was work and work was life’ (Case 6, owner) And, in the case of the SEW dimension (3), related to binding social ties, interesting quotes were, for instance: ‘My father told me, “We are 300 people in this firm. Multiply this by 3 members per family, and you’ll have the number of people depending on you!”’ (Case 1, current F-CEO); and ‘During the COVID-19 pandemic, we did not want to lose the relationship with the employees, and we kept the jobs open ..,’ and ‘..right now, if I had to shut down the firm, I would do anything to help my employees’ (Case 6, family owner).

In turn, the SEW dimension (4), emotional attachment that can be related to a sense of legacy, is visible, for instance, in ‘Legacy is also important, we cannot betray it’ (Case 3, family owner) and ‘There are values that were instilled in me by my dad; now I know that I have to apply and transmit these values’ (Case 6, family owner). Finally, for the SEW dimension (5), renewal of family bonds to the firm through dynastic succession, example quotes are: ‘I feel it is my duty to give continuity to the firm’ (Case 4, current NF-CEO) and ‘My dad had planned that my brother would enter the firm and continue the business, but he wasn’t interested, so I stepped in…and now it’s been a nice surprise that my son is interested and joined in…’ (Case 6, family owner) and ‘My dad never said whether I had to work in the firm or not, but it was something that had always been taken for granted’ (Case 6, successor).

Investment in specific human capital

Successful NF-CEOs

A double investment by the NF-CEO in knowing both the firm and the family, and the family knowing the NF-CEO, characterize the successful experiences analysed: ‘… I became external advisor to this FF. After two years of the firm’s bad results, I got offered the position of NF-CEO. The main advantage was that I already knew the family and the former board of managers and the firm… I know all the members of the family’ (Case 4, current NF-CEO). This NF-CEO is now 54 years old and training the future president of the board of directors, as family members are banned from being CEOs. On the side of the owner family, the successor declared that ‘a good NF-CEO is someone who is aware that they will have to spend a good portion of their time managing the owner family and making them part of the decisions.’ Meanwhile, in Case 3, the NF-CEO declared that ‘the owner and I didn’t know each other, but our personalities and values fitted. I entered the firm aiming at the CEO position, going through a 7-year period of getting to know the firm… after all, you will be deciding on the family heritage. The process cannot be done in 1 year. It is all based on trust.’ This NF-CEO is now 58 years old and has been in the firm for 11 years. The family leader has a 23-year-old son, who is not a fit for a managerial position, and a 21-year-old daughter who has since attended some meetings at the firm. In Case 2, the current NF-CEO explained that ‘I’ve been in the firm for 33 years… I started as Head of Human Resources and went through different sections of the firm until, very informally and gradually, becoming the CEO (about 15 years ago),’ and ‘…I see previous acquaintance, personal relationships and aligned values as crucial.’

Life-cycle considerations also play a part in successful NF-CEO experiences. The age of the NF-CEO facilitates their readiness to teach the designated successors rather than perceiving them as a threat. For instance, the current NF-CEO of Case 4 declared that ‘this is a long-term project. I am committed to the continuity of the firm and currently training the family successor,’ and the NF-CEO in Case 2 explained that ‘…it was a relief that there were successors; this is what motivates us, to know that the firm has a future…. I am now training the successors.’ In Case 6, life-cycle issues were sorted out in the following manner: ‘My son joined the firm a few years ago, but the first years at the firm were not good… and having an NF-CEO was a problem. What I (family leader) decided was that he (the successor) should develop a side-project… a business that was his project and that he could develop in a manner that matched his personality.’

Unsuccessful NF-CEOs

Most unsuccessful experiences appear to have been due to conflicts arising over NF-CEOs making strategic decisions, a lack of trust, or other family members preferring to pass the baton to their offspring rather than to an NF-CEO. Two examples of the first and second issues could be the following: ‘The NF-CEO took too many decisions concerning details of the investment being made in a new factory on his own. That angered my father, who didn’t trust him from then onwards. He felt that the NF-CEO had values that didn’t fit…The NF-CEO he should have sought consensus’ (Case 1, current F-CEO), and ‘We hired three NF-CEOs with an MNC (multinational) profile … They made decisions without consensus, which the family allowed, but the tension was growing underneath. Then, there was a loss of trust when things went wrong’ (Case 4, designated successor). And two examples of family members preferring to pass the baton to their offspring rather than to an NF-CEO could be the Case 5 and 7: ‘The first three years were fine but afterwards I had the feeling that something was going wrong…maybe I should have fired him right away. But one day I talked to my daughter, and she decided to join the firm as Head of Operations, and two years later we fired the NF-CEO and she took over’ (Case 5, family owner) and ‘The guy who used to be the NF-CEO left a year after I joined the firm… the three sibling owners had power stakes, and that was a bit distressing… Later on, we tried internal promotion. The Financial Director was promoted to CEO, but she suffered a lot and left.. The current CEO, daughter and niece of the owners, entered the firm the same year. Everyone is happy now’ (Case 7, NF-manager).

Professional background and personal profile of the NF-CEOs

The professional background of the NF-CEOs varied across the cases studied. In most instances, previous experience at MNCs was sought. For instance, in Case 1, the current family CEO explained that ‘I would rather hire an NF-CEO with experience in MNCs, signalling a higher professional level, than use internal promotion…But you must be careful with the candidates coming from MNCs. We decide on new recruits by their profile, and many are pure reds, and they are too aggressive, too short-term focused.’ However, in Case 4, the family successor said, that ‘we have had four NF-CEOs. We hire executives from MNCs, although in some cases experience in FFs is preferred,’ and in Case 3, the current NF-CEO explained that ‘I have always worked in FFs. 20 years at the same firm before joining the current one. I like the FF model.’

The personality of NF-CEOs is also relevant: a cooperative, long-term-focused personality seems to fit in FFs. To this effect, in Case 3, the current NF-CEO declared that ‘we hire according to personality, someone that can fit in in the firm, and the firm can provide the training. We want people that look for stability, people that are not too aggressive’; and in Case 4, the current NF-CEO stated that ‘after a career at MNCs, I retired in my 50s. I didn’t want to go back to MNCs. The style was too aggressive, people were too ambitious, positions were too demanding,’ and the family successor at the same firm explained that ‘we hired NF-CEOs with an MNC profile. The difference in cultures was seen as an advantage to bring about change, but it didn’t work. Profiles that are too aggressive do not work in FFs. This was the main reason for the “failure” of the three former NF-CEOs’.

On the side of the CEO, issues relating to their life cycle are mentioned as the reasons for wanting to work in POFFs. For example, in Case 3, the current NF-CEOs declared that ‘I value the long-term orientation, the project; and I also value knowing the owner’; and in Case 2, the successor explained that ‘we have been hiring people that have grown tired of working at MNCs, that are looking for something more personal, want to get more emotionally involved.’ Lastly, in Case 6, the NF-CEO said that ‘.…I am involved in the firm project even without being part of the family because I’ve been here for many years, and it is my life project. I am aligned with the values of the place where I am working.’

Family offspring becoming ready or almost ready to take the baton also coincided in some instances with the firing of an NF-CEO, although no explicit relationship to this effect was acknowledged by the interviewees.

Discussion

Consistent with SEW preferences, the interviewees explicitly declared their preference for a family CEO when there is a capable and willing candidate. With regards to the reasons for hiring NF-CEOs, the interviewees mentioned the need to professionalise the firm and the owner lacking the capability to do so, the successors being too young, the family leader having other, sometimes entrepreneurial, interests, and family complexity. These motives for hiring NF-CEOs are in accordance with the findings in the literature (Hiebl & Li, Reference Hiebl and Li2020).

With regards to the reasons for not hiring an NF-CEO, the SEW motives have been found relevant in all cases. The opportunistic (agency) behaviour of NF-CEOs has been signalled as the most common cause for firing NF-CEOs. Lack of trust on the part of the owner family concerning decisions taken by the NF-CEOs was mentioned in Case 1, Case 4, Case 5, and Case 7. In all these cases, risk-taking by the NF-CEOs was judged as excessive by the owner family, and the CEOs were fired allegedly due to a breach of trust. In other cases, the FFs had limited the NF-CEOs’ decision-making rights on corporate investment decisions to reduce agency problems, thus enhancing monitoring mechanisms and preserving SEW (Case 3, Case 4, Case 5, Case 6, and Case 7). In this regard, the results coincide with (Cater & Schwab, Reference Cater and Schwab2008; Gurd & Thomas, Reference Gurd and Thomas2012; Miller, Le Breton-Miller, Minichilli, Corbetta & Pittino, Reference Miller, Le Breton-Miller, Minichilli, Corbetta and Pittino2014).

Prior to hiring an NF-CEO, POFFs invest in getting to know the NF-CEO candidate to reduce information asymmetries. A means to do this is by promoting internally (Case 5, Case 6), hiring social acquaintances (Case 1, Case 2, Case 4), and/or delaying the full tasks/decision rights corresponding to the CEO position (Case 3). The long tenures of some NF-CEOs (Case 2, Case 3) also contributed to developing psychological ownership and favoured stewardship behaviour: These managers considered themselves as having been more risk-averse than the family owners. In this regard, our results concur with (Hall & Nordqvist, Reference Hall and Nordqvist2008), who find that close relationships with owner families help non-family managers perform better as they are more likely to display stewardship behaviour (Zhu, Chen, Li & Zhou, Reference Zhu, Chen, Li and Zhou2013).

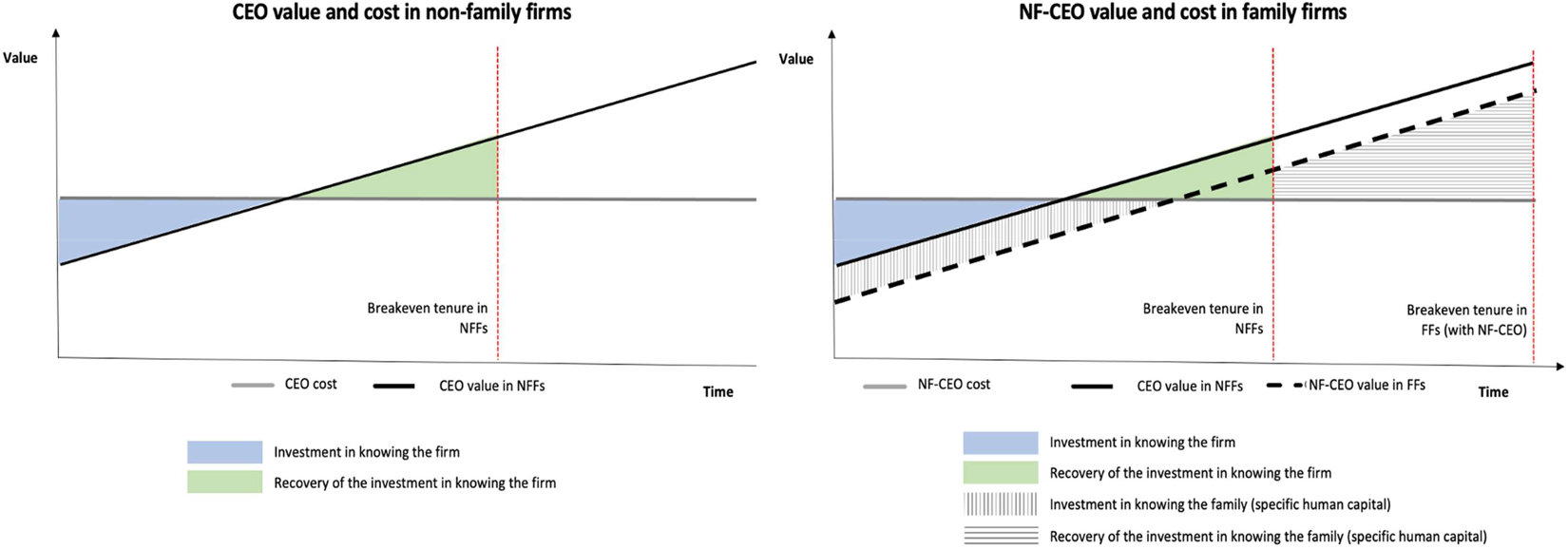

Importantly, the NF-CEO candidates must invest time in getting to know the family, given that its SEW characteristics influence the management of the POFF. This double investment in getting to know each other—the family and the firm on one side, and the NF-CEO on the other side—relates to the specificity of human capital (G. Becker, Reference Becker1975). During this initial period of the professional relationship, productivity is lowered due to a lack of knowledge about the firm and the family on one side, and a lack of knowledge and trust on the other side. Gaining knowledge about the family leads to longer required minimum tenures for NF-CEOs to offset the initial costs of hiring an NF-CEO in FFs in comparison to hiring a CEO in NFFs (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. CEO and NF-CEO value and cost in FFS and NFFS.

Given the high cost and time required for this dual investment, the short- and medium-term benefits of appointing a non-family CEO are comparatively lower than those associated with hiring a CEO in a non-family firm, ceteris paribus. This results in a negative impact during the initial stages of the tenure. However, extended tenures contribute to strategic stability, better alignment of incentives, and ultimately enhance the returns on shared human capital investment (Hashimoto, Reference Hashimoto1981), as well as facilitating psychological ownership (Huybrechts et al., Reference Huybrechts, Voordeckers and Lybaert2013). In contrast, shorter tenures—more prevalent in non-FFs (Cruz et al., Reference Cruz, Gómez-Mejia and Becerra2010)—may lead to inefficient separations, such as premature dismissals (Hashimoto, Reference Hashimoto1981). However, longer tenures may also come with trade-offs, such as an overdependence on or entrenchment of NF-CEOs (Antounian et al., Reference Antounian, Dah and Harakeh2021).

When there are potential successors and they are ready to take over, albeit not explicitly acknowledged by the participants, the NF-CEO may be dismissed and replaced by the family successor (Case 5, Case 7). Anticipation of this potential threat may discourage candidates from becoming NF-CEOs (as in (Fang et al., Reference Fang, Randolph, Memili and Jj2016)—. At the same time, older NF-CEOs are more likely to agree to training the family successors (Case 2, Case 3, Case 4). The matching of the required minimum tenures with the NF-CEOs and family life cycles determines the feasibility of successfully employing NF-CEOs (Case 4, Case 3, Case 2, Case 6). This necessary condition for successfully hiring an NF-CEO is one of the main contributions of the article. While previous literature has already found that CEOs in FFs have longer tenures than CEOs in NFFs (e.g., Tsai, Hung, Kuo & Kuo, Reference Tsai, Hung, Kuo and Kuo2006), arguably due to longer tenures of CEOs belonging to the owning family (e.g., Hiebl & Li, Reference Hiebl and Li2020), our findings suggest the need for a longer tenure of NF-CEOs in FFs due to the longer-term investment in specific human capital required to know both the family and the firm. To the best of our knowledge, no previous work has applied the theory on the specificity of human capital to the literature on POFFs.

Some professional and personal profiles of managers are more suited to the NF-CEO post: managers who accept limits on decision rights, are interested in being part of a project (long-term oriented), and have a cooperative personality, which goes hand in hand with the long-term focus. A means to identify this profile is to hire candidates who have previous professional experiences in FFs (Case 3). In this line, (Hiebl, Reference Hiebl2015) finds that non-family managers with previous experience in FFs are more valuable to FFs as they know which methods work well in this context. Alternatively, professional experience in MNCs can signal candidates’ professional capabilities (Case 1, Case 4). MNC professionals, willing with age to change to a more project-oriented and cooperative environment, can be valuable managers (Case 4). In this respect, also showing up in the cases studied was the less aggressive management style that characterizes FF management in comparison to MNC management, which is in accordance with the long- versus short-term view of the organizations. Overall, the most common NF-CEO profile encountered in our analyses was that of a professional with previous experience in MNCs. Among this group, the most successful experiences correspond to the NF-CEOs who, sometimes with age, value the emotional attachment and the long—term focus in FFs, organizationsprefer some degree of cooperation to competition, and whoinvest in knowing the family. Our findings are in accordance with (Blumentritt et al., Reference Blumentritt, Keyt and Astrachan2007) and (Chrisman, Chua, De Massis, Frattini & Wright, Reference Chrisman, Chua, De Massis, Frattini and Wright2015), who highlight the importance of a similar cultural background to that of the owner family.

On the other hand, these results differ from a strand of the literature that acknowledges a ceiling on the degree of decision-making power that characterizes NF-CEOs in FFs, considering it a limitation that will diminish the pool of candidates (and hence the quality) from which the FF will be able to recruit managers (Chrisman et al., Reference Chrisman, Memili and Misra2014; Chua, Chrisman & Bergiel, Reference Chua, Chrisman and Bergiel2009). By introducing heterogeneity of managers, the right approach to hiring NF-CEOs becomes that of a matching issue: an NF-CEO manager who accepts limits on decision rights and is long-term oriented and cooperative may lead to superior outcomes (depending on the environment) than those achieved by competitive NF-CEOs. Although heterogeneity of NF-CEOs has previously been explored in the literature (Waldkirch, Reference Waldkirch2020), this article makes a contribution by highlighting the adequacy of matching a specific profile of NF-CEOs with the specific needs of POFFs.

Our results highlight the importance of specific human capital investment in the hiring process within FF settings. In the case of NF-CEOs, this investment extends beyond acquiring firm-specific knowledge to include an in-depth understanding of the owner family. Additionally, agency-related concerns on the part of the firm suggest the need for proactive efforts to reduce information asymmetries—particularly regarding the NF-CEO’s formal competencies and cultural fit, both with the organization and the family. This dual investment in specific human capital—organizational and familial—necessitates longer minimum tenures to yield effective outcomes. The alignment of these tenures with both the NF-CEO’s professional trajectory and the family’s life cycle plays a critical role in determining the success of such appointments. Furthermore, personal attributes such as long-term orientation, willingness to accept limited decision-making authority, and a cooperative disposition facilitate a smoother integration of professional executives into POFFs.

Conclusions

This study investigates the experiences of seven POFFs in hiring NF-CEOs, examining the reasons for hiring and not hiring them, as well as the professional and personal profiles of these NF-CEOs. By obtaining detailed qualitative information on the cases analysed, this article contributes to the understanding of why some management experiences of NF-CEOs in POFFs are successful, while others are not.

While the reasons for hiring and for not hiring NF-CEOs encountered in this study are basically in agreement with results that are widely recognized in the literature, other findings highlight the timing conditions that make possible the double investment in specific human capital—knowing the firm and the family—that characterizes management in FFs. due to this longer double investment, the minimum efficient tenure for an NF-CEO is longer in POFFs than in NFFs. In this vein, since the availability of successors can be seen by potential candidates as a threat to becoming NF-CEOs, appropriate matching of the life cycles of NF-CEOs and the successors is a requisite for success.

Moreover, while there is already interesting work on the professional and personality profiles of NF-CEOs, recent literature reviews call for more research in this line. To this effect, this article contributes to the literature by highlighting the suitability of accounting for the heterogeneity of NF-CEO candidates when seeking a match with the specificities of POFFs.

For families considering the appointment of an NF-CEO, our findings suggest strategies to address trust issues and potential opportunism. Selection is key: internal candidates, those previously known, or those with prior experience in FFs help reduce information asymmetries. Attention should also be given to the candidate’s cooperative personality and career stage. Beyond selection, managing the relationship is essential—gradually increasing decision rights while reducing monitoring systems can foster trust. Maintaining psychological ownership through deep, ongoing communication is also critical. Together, these strategies support a smoother integration of the NF-CEO and increase the likelihood of success.

While this article makes several contributions, it is not without limitations, which are mainly related to our findings being contingent upon the sample selected. The fact that the firms in the study are in the same region eases the comparison among them, but at the same time, this may limit the validity of the results since the culture and regulations of a given region may influence the behaviour of the firms. To this effect, more research is needed that extends the current research to other cultural and regulatory environments. Second, and as with other multi-case studies, while the strength of this study lies in the richness of the data that can be obtained at the individual level, for obvious reasons, the findings have no statistical validity. The sample size constraints the findings to be explorative, and research with larger samples is required for their furthervalidation.

Finally, and despite these limitations, our article is valuable for addressing a critical issue, especially relevant for the survival and success of FF. These firms often struggle in searching for a fit between internal, family, and external, non-familyThese CEO candidates. We find this fit when aligning personal attributes, life cycles, and contextual familiarity between NF-CEOs and family firm owners, considering them all key to fostering sustainable leadership and long-term success in POFFs.

Acknowledgements

The authors have received support from the Chair of Family Business at the University of Girona and from the Catalan Government Research Grant 2021SGR01589. Open Access funding was provided based on an agreement between Universitat de Girona and Cambridge University Press.

Anna Arbussà, PhD, is an associate professor in the Department of Business Organization, Management, and Product Design at the Universitat de Girona (Spain). Her research interests include family business, technology management, and innovation management. Recently, she has also participated in local projects on family business and the adoption of new technologies.

Pilar Marques, PhD, is an associate professor in the Department of Business Organization, Management, and Product Design at the Universitat de Girona (Spain). She currently serves as the director of the Chamber of Commerce Chair of Family Business at the same university. Her ongoing research endeavours revolve around family businesses, particularly emphasizing transgenerational dynamics and innovation.

Andrea Bikfalvi, PhD, is a “Serra Húnter” associate professor in the Department of Business Administration and Product Design at the Universitat de Girona (Spain). A teacher of strategic management and Innovation management and deputy director of the Chamber of Commerce Chair of Family Business, her main research interests are in strategy, entrepreneurship, and holistic approaches to Innovation in all types of organizations.