It is more important to find out how responsive a child is to intervention than to focus on what she already knows. (Lidz, Reference Lidz1991)

What we know from Australian government surveys is that 14% of children and young people between the ages of 4 and 17 years have either mental health or behaviour difficulties (Sawyer et al., Reference Sawyer, Arney, Baghurst, Clark, Graetz, Kosky and Zubrick2000). We also know that for every four young people with mental health difficulties, only one of them receives professional care and support (Sawyer et al., Reference Sawyer, Arney, Baghurst, Clark, Graetz, Kosky and Zubrick2000). School-based counsellors and psychologists are the most likely sources of mental health support that adolescents access, while under-12-year-olds tend to be supported more by family doctors and paediatricians. It is alarming to learn that only 50% of young people with serious mental health difficulties are accessing the support they need. Some of the reason for this is lack of parental resources, either financial, or of local knowledge, or an unwillingness to create a support network (Sawyer et al., Reference Sawyer, Arney, Baghurst, Clark, Graetz, Kosky and Zubrick2000). Yet we know that there is a strong link between academic success and mental health and wellbeing (Guzman et al., Reference Guzman, Jellinek, George, Hartley, Squicciarini, Canenguez and Murphy2011; Zins, Bloodworth, Weissberg, & Walberg, Reference Zins, Bloodworth, Weissberg, Walberg, Zins, Weissberg, Wang and Walberg2004), so it is easy to argue for aspects of treatment and support relating to mental illnesses and disorders to be delivered at school. However, many post holders in school guidance/counsellor positions have very little autonomy over case management, and their managers, usually the school principal, actively discourages them from providing direct mental health support by urging them to refer on to community agencies. Additionally, in supervision, this is reinforced as some regions have senior guidance officers who are not registered psychologists or counsellors and would not have direct experience of diagnosis or the delivery of treatment options. Yet we know that early intervention to support relief from psychological suffering is vital, and that there is a lack of specialised mental health support in the community (McGorry, Reference McGorry2014). Erikson (Reference Erickson2013) reminds us that the prevalence of mental health issues and suicidal thoughts and actions among school-aged children and adolescents is seriously high. We also know that parents and carers urgently require education to make informed choices about mental health intervention for the children in their care. Additionally, we are also aware of the ongoing grief they experience when faced with the learning and developmental needs of their child, along with its accompanying burden and stigma (Rivers, Reference Rivers2009). Foster carers are particularly in need of this as often very vulnerable children with undiagnosed mental health conditions enter their care at short notice. New figures from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW; 2014) report that 135,139 children were the recipients of child protection services in 2012–13. Most of these will be enrolled in schools, with very little information accompanying them.

What is proposed here is that school-based guidance officers/counsellors/psychologists need to be proactive in creating comprehensive psycho-educational assessments for these children on enrolment, which includes screening for mental health and wellbeing issues. We know that even if they are not presenting with issues on enrolment, these children are at high risk of developing mental health issues. It is also important that these school-based mental health professionals are better prepared, with professional development opportunities. These opportunities need to contain critical content and authentic experiences that provide the necessary skills in assessing and providing timely advice to teaching staff and parents that suits the changing needs of both students and schools (Wnek, Klein, & Bracken, Reference Wnek, Klein and Bracken2008). What has been observed repeatedly as part of an education program for children in out-of-home care across more than 50 schools in South East Queensland is that psycho-educational assessments tend to be both static and reactive (Mainwaring, Reference Mainwaring2014). A case study follows that intends to illustrate the unique contribution of educational and developmental psychologists working in liaison with schools and care teams, and assisted by psychologists in training to provide timely, comprehensive advice that encourages reflective teaching practice and transforms both the school and care environments, such that they are more likely to promote the learning and development of children in out-of-home care.

Case Study DJ

DJ was referred to our educational and advocacy service by the specialist foster care agency managing her case. DJ remains a subject of a Long Term Care Order under the Child Protection Act (Qld) 1999. DJ was 13 years old at the time and had just voiced her desire to be reunited with her siblings. She was also due to transition to high school. She had been removed from her birth parents at the age of 4 years due to evidence of consistent neglect and drug dealing. She had then been placed in kinship care but there were concerns about the carers’ capacity to provide her with the care and support she needed. A provisional psychologist (Educational and Developmental) had been introduced to DJ as part of a recent request to review her cognitive abilities. Despite the fact that she had been in care for the past 9 years and was struggling with her learning, the only academic intervention that had been offered by the school over the past 12 months was for her to repeat Year 5, even though such a practice without additional interventions is one of the least effective forms of intervention and likely to lower her feelings of self-worth further, particularly as her younger sibling was now in the same grade.

Over the 5 years she had attended the school no investigation had been completed into her abilities to think and reason, no additional speech and language intervention was being provided at school (as her scores fell above the 5th centile and only those below were eligible for support), there been no assessment of her wellbeing even though the teacher had anecdotally reported that she appeared extremely sad, and that two placements had broken down that year. The school Guidance Officer (GO) was keen to work with us as DJ had been on her ‘list’ for counselling because she was struggling with peer relationships; the GO was concerned that two girls with whom she had attempted a friendship may be at risk of vicarious trauma due to disclosures she had made to them about her parents’ drug use and their neglect of her. We advocated for GO involvement with the school principal on the grounds of McGrath's research (Reference McGrath2007), which shared that the most important factors that ensured a school was able to be safe, supportive and inclusive was whether it: (1) made pupil wellbeing a high priority; (2) focused on the development of a positive peer culture; (3) had leaders who focused on wellbeing of the whole community and the personal development of its students; and (4) had operationalised a school wide positive behaviour support plan.

The Provisional Psychologist (PPED) commenced the Wechsler Nonverbal Scale of Ability (WNV; Wechsler & Naglieri, Reference Wechsler and Naglieri2006) because of DJ's known speech and language difficulties. The results would provide more evidence of DJ's failure to learn, but nothing practical to share as recommendations to the teacher on how to improve engagement and increase literacy and numeracy competence. The profile showed her in the low average range of abilities to think and reason (FSIQ = 88). The Care Team felt that this profile would serve to lower expectations of her further, and the PPED was struggling to know how the result would inform the class teacher of suitable strategies to improve DJ's cognitive engagement with tasks and learning. The Principal Educational and Developmental Psychologist (PEDP) suggested that a dynamic assessment of DJ's developmental and learning profile commence. The whole stakeholder group was involved in completing the baseline measures for the Cognitive Abilities Profile (CAP; Deutsch & Mohammed, Reference Deutsch and Mohammed2009), and the PPED was able to bring the views of DJ, including that she wanted to be placed with some of her siblings, to the stakeholder meeting. Subjective tools that were used that prompted this sharing were: the Preferences for Activities for Children (PAC; King et al., Reference King, Law, King, Hurley, Rosenbaum, Hanna and Young2005), to share with the school a range of her preferred activities; the Resiliency Scales for Children and Adolescents (RSCA; Prince-Embury, Reference Prince-Embury2005), to gain a sense of her perceived resourcefulness and vulnerability; and the Behaviour Assessment System for Children, 2nd Edition BASC2 — Self-Report (Reynolds & Kamphaus, Reference Reynolds and Kamphaus2009), to assess her perceptions of her social, emotional and behavioural functioning. The BASC2 Teacher Rating Scales were completed with her class teacher and the BASC2 Parent Rating Scales were completed with both her current foster carer and her case manager, who had been involved in her care planning for the past 9 years. The RSCA outcomes were able to inform future educational and care planning as it revealed her perceived lack of self-efficacy in relation to tasks set (before she even attempted them) and difficulties in feeling a sense of relatedness, including lower comfort and support when compared to her peers and a poorer recovery rate following emotional upsets that was impacting on her ability to return to the classroom following an upsetting event. While the BASC2 Self-Report revealed that DJ perceived her social skills to be within the normal range, this was not supported by observation of her relating to peers in class and around the school; both her teacher and case manager agreed that she needed support in asking for help, and regulating her emotions and functional communication to aid cooperation with social and academic tasks.

When the Child Safety Officer called the Care Team to share that the sibling placement had been approved, the PPED was able to show DJ a social story that involved her siblings and the carer they were all going to live with, which the PPED had made on an iPad using the Pictello app (Pictello, 2013). She was also able to show pictures of the P-12 school where DJ was going to be with her siblings. DJ was keen to attend the school with her siblings, and the multiagency/ multidimensional assessment that had taken place was shared with the new school so that the process of verification of her social and emotional needs could occur prior to her transition.

There was still a whole term of attendance left at her existing school, and the GO and PPED were able to run a Friends for Life program with DJ and three other children she had disclosed to and who she identified as her ‘friend’. All of them had significant resiliency concerns of their own. Additionally, the GO and the PEDP were able to run a 10-week CBITS® (Cognitive Behavioural Intervention for Trauma in Schools; Jaycox, Reference Jaycox2004) program with DJ and five other children who had been screened in the local school cluster as meeting criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). DJ transitioned to the new high school with an adjusted timetable, to focus on supporting her social and emotional needs and building on her interests and strengths, as informed by the CAP baseline.

Professional development was delivered to key school staff on the pupil-free day prior to DJ's transition and to the Care Team about support required to facilitate a smooth transition to the new school by the PEDP and PPED. The PPED spent time with DJ reviewing some of the outcomes of the social and emotional assessments (RSCA, BASC2-SR as well as the PAC) and setting goals to support her concerns with friendship (new school), ‘trust’ development with the new carer, self-esteem when dealing with her siblings and CAP-informed interventions to scaffold literacy tasks in particular. Scaling tools, psycho-education, psychodrama, as well as sand play and symbol work, all proved useful for proactive training in social skills (particularly social introductions, friendship maintenance, assertiveness, relaxation and conflict resolution). Psychodrama and sandplay therapy were selected as contexts for learning social skills on the basis of the CAP informing the stakeholder group that DJ's preferred modality was kinaesthetic; and because of her impaired language development, sandplay therapy was preferred as a vehicle for DJ to explore and process past hurts and promote self-regulation and healing. Painting proved to be DJ's preferred method of integrating outcomes of psychodrama and sandplay sessions, as well as a self-soothing tool. Apps were placed on her iPad that supported the key social, emotional, and learning goals from both subjective and objective (teacher, carer BASC2) reports and observations made by the PEDP over a period of 6 months during school/ home visits (old school and kinship placement) and visits to siblings in the proposed placement and school environments.

An additional request from DJ's Legal Guardian at the Department of Child Safety was to explore how much of her past trauma was still impacting on her functioning. While this was a challenging request, the PEDP negotiated that as part of the overall wellbeing assessment there would an exploration of DJ's PTSD. Therefore, additional assessment tools were selected: The Initial Trauma Review (ITR-A; Briere, Reference Briere2004), completed as a self-report and the the Trauma Symptoms Checklist for Children (TSCC; Briere, Reference Briere1996), completed with the case worker who had known DJ for the past 5 years. The PPED continued to meet DJ on a weekly basis to work on intervention goals and monitor her wellbeing indicators. The PEDP made regular communications with the new school and the care team on a monthly basis to track DJ's progress and monitor the school and care settings, to maximise their potential as safe places for DJ. The PEDP completed a review of the CAP after 6 months in the new settings, working alongside the class teacher to develop strategies to facilitate mediated learning experiences for DJ.

Dynamic Assessment Defined

The UK's New Economic Foundation (NEF; 2008) proposed that children's wellbeing needs to be considered as a dynamic process, in the way that Bronfenbrenner (Reference Bronfenbrenner2005) demonstrated his bioecological model of human development occurring over time. Following this framework, influences external to the child, such as parental capacity and school ethos, interact dynamically with internal influences within the child, such as their ability to think and reason and their sense of self, to meet their needs and build resilience and capabilities to deal with life stressors (or not as the case may be). One of the major goals of psychoeducational assessment is to classify the child or young person according to their academic competency, to be able to inform the teacher how to group the student to enable differentiation of instruction. The preferred tests for this task tend to be based on normative, standardised assessment tools. However, these tools do not lend themselves to advising the teacher on how to operationalise the adjustments to tasks or provide the specific skill steps to improve competency.

It has been an observation during the delivery of a recent program targeting the educational outcomes of children in out-of-home care that many children with complex trauma histories produce low average profiles on tools such as the WISC-IV, and even though the report from the assessor qualifies that the child's results may have been affected by poor early language experiences (typical of children with trauma histories), the teacher sighting the scores will have lower expectations of the child's attainment; as predicted by Brophy and Good (Reference Brophy and Good1970) when demonstrating the self-fulfilling prophecy. Additionally, we know from a wide range of research studies (including neuroscience) that IQ (learning capacity) is not fixed but has the potential to increase. Feuerstein (Reference Feuerstein1979) described this process in his theory of structural cognitive modifiability, of how through structured teaching an individual's learning could be mediated by those around them (the mediated learning experience or MLE). Feuerstein, Haywood, Hoffman, and Jensen (Reference Feuerstein, Haywood, Hoffman and Jensen1986) proposed dynamic assessment to help answer specific questions. Of course, standardised normative assessments are still helpful for the verification of special educational needs for funding purposes, but when decisions need to be made about individuals whose low performance on these tests has an alternative explanation (such as trauma) then dynamic assessment is required. What dynamic assessment can provide is: a baseline measure of performance (no assistance); how much and what type of help is required to help raise their achievement; and how a child/young person responds to that help in ways that demonstrate new learning and the application of new skills. Both Lidz (Reference Lidz1987) and Tzuriel (Reference Tzuriel1989) discuss dynamic assessment approaches, and the one used in the current study is the CAP (Deutsch & Mohammed, Reference Deutsch and Mohammed2009). This tool is used to assess: the child's maximal (rather than typical) performance; their preferred learning style (rather than how much they know); which teaching pedagogy is required to support an acceptable level of learning in the child (rather than at which level they can learn independently); what type of process deficits lay behind the failure to learn previously, as well as providing a guide to correct these in future learning opportunities (rather than assessing what content was missed).

We assist each child through demonstration, leading questions, and by introducing elements of the tasks solution. (Vygotsky, Reference Vygotsky, Rieber and Carton1934/1987, p. 209)

Wellbeing Defined

The process of multi-dimensional, dynamic assessment is not just true of development in the cognitive domain, but also the social and emotional domains. Seligman (Reference Seligman2011) and Forgeard, Jayawickreme, Kern, and Seligman (Reference Forgeard, Jayawickreme, Kern and Seligman2011) proposed that wellbeing cannot be explained by a single measure but is ‘best understood as a multifaceted phenomenon’. When using Seligman's PERMA model (Reference Seligman2011), we are guided to explore: positive emotions (such as feeling happiness/joy); engagement (such as a sense of connection with what you are doing or with an organisation's identity and values); positive relationships (such as a sense of belonging and receiving care and support from others); meaning (such as self-belief and self-worth and a sense that one is part of a wider community); and accomplishment (such as sensing that goals are both attainable and being accomplished). Wellbeing thus needs to be understood not as sets of entities to be acquired as internalised qualities of individuals, but instead as a set of effects produced in specific times and places (Kesby, Reference Kesby2007). In the case of DJ, the CAP provided the vehicle to maximise both her engagement and accomplishment when introduced to new tasks. Her teacher's improved insight into her social, emotional and cognitive functioning also fostered a sense of being supported and developed her mastery of tasks and skills overall.

Complex Trauma (CT) Defined

The Chadwick Centre for Children and Families (2009) defined the term ‘complex trauma’ as: ‘both children's exposure to multiple traumatic events . . . often of an invasive, interpersonal nature — and the wide-ranging, long-term impact of this exposure’. Courtois and Ford (Reference Courtois and Ford2009) have defined CT as occurring following severe stressor exposure that can be from witnessing acts of domestic violence and/or direct acts of abuse (emotional, physical, sexual) and neglect that is perpetrated by or condoned by caregivers or significant adults expected to provide stability, security and protection, repeatedly and over an extended period of time. The events alluded to tend to be both pervasive and severe, such as repeated experiences of abuse and neglect. The child mentioned in this case study was typical of this type of trauma, having experienced abusive events in utero, then throughout infancy, and while in care. The referral to the author had come about because of a request to investigate the extent to which these early events continued to impact on DJ's development and, in particular, her sense of self.

Attachment Theory Defined

Bowlby (Reference Bowlby1982) defined attachment as an aspect of the child and carer relationship that makes the child feel protected, secure and safe (Bowlby, Reference Bowlby1982). Four types of infant-parent attachment have been identified: three organised types (secure, avoidant and resistant) and one disorganised type (Ainsworth et al., Reference Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters and Wall1978). Attachment quality developed between an infant and carer is influenced by how the carer responds when the child feels threatened physically or emotionally (activated). From 6 months of age, on average, a child will start to anticipate how their carer will react to distress and this will precipitate a series of behaviours in the child. In the case of DJ, she experienced disorganised attachment with her mother as she alternated between feeling secure with the mother and then fearful. In more recent years she has acted as a caregiver for her mother.

Attachment in the Context of Complex Trauma

Since traumatic events tend to occur in the context of the child's relationship with their carer, they interfere with the formation of a secure attachment to the carer. Yet a large body of research tells us that for a child to develop into a physically and healthy adult they require the assurance of receiving consistent unconditional positive regard, safety and security from their primary carer. A child such as DJ, who witnessed repeated acts of domestic violence, was then removed from her primary carer, separated from siblings and placed with a foster carer. Unfortunately, as is the case for many children in the care system, the abuse did not remain in the past but is revisited during inadequately supervised family contact. This has ongoing effects on the child's personal, social, emotional, behavioural and cognitive functioning (required for social and academic learning) and is linked to the development of addictive behaviour, non-suicidal self-injury, depression, anxiety, and chronic physical symptoms that sometimes present as more serious psychiatric disorders (Briere & Lanktree, Reference Briere and Lanktree2012).

Government Wellbeing Policy in Practice

KidsMatter is the Australian Primary Schools Mental Health Initiative (http://www.kidsmatter.edu.au) and is supported by the Australian government. KidsMatter Primary is flexible in its approach, universal in design (it can be customised) and it targets the whole school population to improve wellbeing and mental health for primary schools. Schools can opt for a 2- or 3-year plan to promote: social and emotional learning; authentic partnership with parents, carers and families; and support for students who may be experiencing mental health difficulties. Building on the stage of development, the school as a community is the initiative to encourage the growth of respectful relationships and a sense of belonging and inclusion. DJ's first school and associated cluster schools had participated in KidsMatter whole school programs (primary intervention) and therefore were expected to invest in both group (secondary) and 1:1 (tertiary) mental health and wellbeing intervention. This meant that they were open to screening whole year groups for both resiliency and PTSD and offering their GO to co-facilitate both the Friends for Life ® and CBITS® programs for DJ and others.

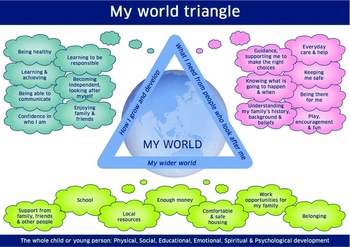

Research informs us that improvements in the way children feel and function contributes to better policy outcomes. School-based screening tools are crucial for this purpose, particularly as many past hurts in children are internalised. The Scottish government initiative, Getting it Right for Every Child in Scotland, has developed My World Triangle (see Figure 1) to inform their integrated assessment factors that share wellbeing from the child's perspective.

FIGURE 1 Wellbeing Wheel (Crown copyright 2012; http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Resource/0045/00458341.pdf).

Peterson (Reference Peterson2006) defends schools as ideal settings to provide opportunities for the promotion of wellbeing. Similarly, this research proposes that assessments of wellbeing need to go beyond global assessments to share specific information with teachers and school guidance officers/counsellors/psychologists about the primary areas of support required for each child, as well as their main areas of strengths. Systematic assessment of social and emotional functioning tends not to happen in the majority of schools (e.g., Civic Enterprises, Bridgeland, Bruce, & Hariharan, Reference Bridgeland, Bruce and Hariharan2013). Apart from the huge constraints on teachers, school guidance officers, counsellors, and psychologists’ time, even when universal or primary models of intervention to promote wellbeing are occurring in a school, they have little autonomy to implement social and emotional/wellbeing interventions at the secondary and tertiary levels of intervention that children with complex trauma histories and attachment difficulties require. ‘Reading and writing are intentionally taught, but not always resilience and responsibility’ (Civic Enterprises et al., Reference Bridgeland, Bruce and Hariharan2013).

What also needs to be ensured is that wellbeing is understood as not just an internal concept that we assist a young person to acquire, but also as something influenced by temporal and contextual factors (Kesby, Reference Kesby2007). This helps us to focus on adjusting the environment around the child to ensure we are creating ‘spaces of wellbeing’ informed by what we know is most likely to be perceived as a safe space that the child can make a meaningful connection with (Fleuret & Atkinson, Reference Fleuret and Atkinson2007; Hall, Reference Hall2010). This also requires a move away from seeing wellbeing as individually focused to being a collective responsibility; that is, that healthy schools will contribute to a healthy child.

Assessment of Social and Emotional Functioning

Returning to Seligman's PERMA Model (Reference Seligman2011), My World Triangle (see Figure 1; Scottish Government, 2012) and the Wellbeing Wheel (Scottish Government, 2012) in Figure 2 demonstrate how the assessment of a child's wellbeing can occur in a variety of ways; the wheel alludes to the temporal and spatial considerations that need to be considered.

FIGURE 2 My World Triangle (Crown copyright 2012; http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Resource/0045/00458341.pdf).

These frameworks allow a practitioner to organise information from a range of sources and agencies into strengths, needs and concerns, thus informing a plan of intervention. Hypotheses can be made and then tested using standardised assessment tools such as the RSCA, which measures three areas of perceived strength and/or vulnerability related to psychological resilience. In the case of DJ, it was used to measure her sense of mastery (optimism, self-efficacy, and adaptability), sense of relatedness (trust, support, comfort and tolerance), and emotional reactivity (sensitivity, recovery and impairment). This assessment was chosen because of its theoretical base; its concepts are developmentally appropriate for the target client; and it is subjective (providing the voice of the child), user friendly, and easy to score and interpret, with clear links to intervention and future evaluation (Prince-Embury, Reference Prince-Embury2005). Used in combination with the Behaviour Assessment System for Children 2nd edition (BASC-2) by Reynolds and Kamphaus (Reference Reynolds and Kamphaus2012), it was favoured because it applies a best practice triangulation method for gathering information — analysing the child's behaviour from perspectives of self, teacher, and parent, to provide more comprehensive and balanced information. The Community-University Partnership for the Study of Children, Youth, and Families (2011) reviewed the BASC-2 and included its usefulness as a tool to measure aspects of a child's functioning that were relevant for the goals of intervention, including:

• program planning, evaluation, and intervention

• help in determining eligibility for educational verification for special educational needs funding

• help in exploring the function of behaviours observed that may be hindering learning and development for a child with recognised disabilities.

The Use of Observation to Assess Attachment

Using the Wellbeing Wheel as an assessment framework can be an important contribution towards understanding the needs of the client being assessed (Neukrug & Fawcett, Reference Neukrug and Fawcett2010), particularly when the client is observed in different settings and activities, thus enabling the sampling of both frequency and intensity of behaviours over an extended period of time. In addition to traditional classroom-based observations, the PEDP used the Marschack Interaction Method (MIM; The Theraplay Institute, 2011) for assessment of the developing relationship between DJ and her new carer. This tool utilises the principles of Video Interaction Guidance (VIG), where clients are shown clips of their successful interactions and actively guided to reflect on what is happening towards a process of change that aims to strengthen their relationship (Kennedy, Landor, & Todd, Reference Kennedy, Landor and Todd2011). The MIM evaluates the parent's capacity to: provide appropriate boundaries and an environment that is orderly (Structure), be attuned to child's responses and encourage the child to interact with the carer (Engagement), provide care, support and respond to requests for attention (Nurture), scaffold the child's attempts to complete tasks commensurate with their developmental (Challenge). At the same time it allows assessment of the child's ability to respond to the carer's responses. A set of activities that can elicit each of the key focus areas are provided to the carer and child. They are videoed interacting with the activities. The facilitator reviews the video and selects clips as feedback to demonstrate strengths and areas to develop in the relationship. Theraplay interventions are then planned that focus on the key areas that the facilitator can scaffold for change. Thus, mediated learning experiences were created in both care and education settings to promote DJ's learning and development across all domains.

Assessment of Trauma

Children and young people who have experienced trauma can and do experience a wide range of symptoms, and can exhibit a wide range of problem behaviours. Each trauma history is unique, and the nature and severity of these presentations is influenced greatly by the developmental stage of the child or young person; the intensity, frequency, timespan of exposure; as well as contextual factors mediated by a range of possible physical, social and psychological factors that could lessen or intensify the experience for the child/young person (Briere & Lanktree, Reference Briere and Lanktree2012). For this reason, trauma-specific questions, observations and checklists are required to be integrated into the assessment framework, including: evaluation of current safety, evaluation of trauma exposure history, initial trauma review for adolescents (ITR-A), information from caretakers, and a review of trauma-relevant symptoms that can be gleaned from a range of psychological assessments already completed for the child/young person and in terms of carer competency/culture/values and own trauma history as appropriate (Briere & Lanktree, Reference Briere and Lanktree2012). Children who have entered the child protection system have usually been exposed to what is called complex trauma (CT). Cook et al. (2005) place CT symptoms into seven domains of impairment: attachment, biology, affect regulation, dissociation, behavioural control, cognition, and self-concept. In the case of DJ, she showed deficits across all seven domains. The assessments used were made prior to, immediately following and 6 months after the CBITS® was completed, as per program guidelines. The skills DJ had learnt during CBITS® persisted beyond the 6 months following intervention.

Discussion

DJ's case illustrates how the ongoing issues young people in care are confronted with would be challenging to anyone with a highly developed social and emotional profile. It highlights some key roles that professionals can play in being proactive in identifying social and emotional strengths and weaknesses, which can guide targeted intervention. Guidance and learning support staff rarely have the opportunity to do this as they are more often required to look at cognitive functioning and/or identify higher order thinking deficits to guide diagnosis driven support. It would be preferable if the principles of assessment for learning (with a social emotional emphasis) were embedded in this process, such that some form of dynamic assessment was incorporated so that the child becomes more knowledgeable about themselves as a learner; and so that tasks, pedagogy and assessments can be adjusted to suit the child's learning strengths to the point where they have the skills to request those adjustments themselves (Yeoman, Reference Yeoman2008). It is evident that DJ is coping better than expected, given her trauma history, and this is due to the insightful and prompt referrals and actions of her care team. However, although government policy encourages exchange between care teams and school teams, the implementation of these policies (such as the Education Support Plan for Children in Out of Home Care; Queensland Government, 2004) is reliant on strong school and care leadership committed to multi-agency collaboration (Harker, Reference Harker2004; Mainwaring, Reference Mainwaring2014). The Australian state education policy structures can learn much from the Scottish government model, Getting it Right for Every Child in Scotland.

Conclusion and Limitations

Due to the nature of complex trauma and ongoing risks of retraumatisation, and the global impacts on a child's development and learning, a high level of commitment is required to act early (i.e., not wait for crises) and keep the ‘conversation’ going through constant monitoring of wellbeing and cognitive ability indicators, particularly at times of transition, including events with the potential to trigger negative social and emotional outcomes that affect key developmental milestones, as well as when significant social and academic demands are anticipated (e.g., school-based and external academic assessments). Key adults assessing/facilitating interventions with children like DJ need to be part of a targeted induction program themselves prior to taking on these roles, if we are going to attain the goals set for their social and emotional wellbeing. Also, the integrity of program delivery is crucial and needs to be followed closely in supervision so that the principles of best practice delivery are consistently applied in all school, community and care settings with which a young person engages (Briere & Lanktree, Reference Briere and Lanktree2012; Downey, Reference Downey2007; Perry & Szalavitz, Reference Perry and Szalavitz2006).

Ensuring self-determination for the young people we work with for the benefit of their wellbeing is paramount, and a dynamic multidimensional process of cognitive, social and emotional assessment can be the perfect platform to provide adequate opportunities for this to occur, being mindful of the spatial, temporal, and relational contexts that will best facilitate it (Bruskas, Reference Bruskas2008, Kesby, Reference Kesby2007). Although the author does not advocate that school-based mental health professionals should provide long-term therapy for students such as DJ, there is much that they can do to promote their development and learning through advocacy, systematic screening, creating opportunities to work alongside the class teachers to model mediated learning experiences, and through using outreach to smooth the way for transitions and create prompt proactive referrals at times of crisis (ASCA, 2009). Implications for leadership and policy-makers in relation to dynamic assessment relate to time allocation, training and interpretation so that findings can be applied in daily classroom teaching. The focus needs to be on the quality of assessment completed rather than the quantity of children assessed.

Training is a crucial factor. Schools need to have access to senior practitioners with a thorough working knowledge of cognitive functions (not just a cognitive assessment tool). Only practitioners with considerable postgraduate training and experience can effectively utilise dynamic assessment. They also need access to high quality peer supervision and ongoing training as they bear the weight of developing a rationale for test administration, adaptations and interventions selected; rather than passing the accountability for test administration on to a test developer of ‘static’ tests who ‘protects’ the administrator from challenges to the method of assessment.

Another crucial factor for educational leadership in Australia is the continuing emphasis on outcomes and scores. This is often prioritised at the expense of learning how to learn, and children becoming reflective learners and teachers becoming reflective practitioners. It was pleasing to experience the CAP as an ideal tool to empower teachers to be reflective and that became a vehicle for them to acquire a much deeper understanding of not just the target child, but the whole learning environment they were creating for all of the children. Using the CAP, the author was able to observe DJ in her typical learning environment, interview all the adults living and working with DJ, promote formative assessment in the classroom, assist DJ's teacher in mapping a cognitive approach to differentiation, alert the teacher to ensuring she was catering for all learning styles, introduce a tool that combined elements of the task, the teaching methods, and the learner's needs (tripartite model), and create a profile that combined the results of assessments carried out by a range of professionals, thus catering for a young person with complex learning, social, emotional and behavioural needs. It is imperative that there is a move towards investing in doing fewer, more comprehensive and more valuable evaluations of young people's development and learning needs.

Dynamic assessment allows us to gather enough high quality information for us to really begin to understand the often complex needs of children in out-of-home care. As ‘most of you are more concerned with finding the answer than with understanding the problem. . . If we can really understand the problem, the answer will come out of it; because the answer is in the problem, it is not separate from the problem’ Jiddu Krishnamurti (n.d.).

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the support given by Life Without Barriers specialist foster care agency and the Youth + non-schools initiative. Their collaborative program funded the educational advocacy role for children and young people placed in out-of-home care held by an educational and developmental psychologist for 4 years. The author also acknowledges the extraordinary levels of partnership of principals and their staff at Education Queensland, Brisbane Catholic Education and Australian Independent Schools, who embraced the recommendations of the program. The author is grateful for the engagement of Masters of Educational & Developmental Psychology students from the Queensland University of Technology, whose input greatly enhanced the impact of the program. Finally, and most importantly, a special mention needs to be made for the immeasurable contribution of the children and young people themselves to whom this work is dedicated. Their life stories remain sacred — their sharing, acceptance and willingness to trust and aspire towards a bold, bright future continues to inspire me to help empower them and those who care for them and educate them.

Financial Support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sector but the author's salary and materials used during the period of the research was funded by both Life Without Barriers specialist foster care agency and the Youth + non-schools initiative.