Introduction

Since late 2019 the UK Government has been discussing the possibility of allowing dual class capital structures in the premium listing regime of the London Stock Exchange (LSE).Footnote 1 The revival of initial public offerings (IPOs) with dual class share structures in the US and the increasing popularity of such share structures in Asia has put pressure on the policymakers in the UK.Footnote 2 With the recent reform in the leading financial centres, such as Hong Kong, Singapore and Shanghai, many stock exchanges now see permitting dual class companies to list as a necessary step to ‘stay relevant in a time of relentless competition in the cross-border IPO business’.Footnote 3 Discussions around dual class listing are essential if London wants to remain one of the world's leading markets and attract high-tech and innovative companies to list, especially in the context of Brexit and the Covid-19 pandemic.

There is indeed a growing demand for such flexible capital structures among the UK companies. For example, THG Holdings plc (THG) had a dual class IPO on the LSE Main Market's Standard Segment in September 2020. Its founder and chief executive, Matthew Moulding, who retained a 25.1% stake in the company, got one special share, providing him with the ability to pass or prevent the passing of any shareholder resolution, regardless of the support any resolution may or may not have from other shareholders.Footnote 4 While THG's IPO falls short of the classic definition of a dual class listing,Footnote 5 the essence of the special share is to allow the founder to retain control with less than a majority ownership stake in the company, which is not materially different from dual class share structures.Footnote 6 THG raised £1.88 billion in its IPO, making it the best listing in London since Allied Irish Banks’ IPO in June 2017.Footnote 7 More recently, Deliveroo, an online food delivery giant, also chose to list on the LSE with dual class shares, in March 2021. The Class B shares under the dual class structure provide the founder with 20 votes per share while holders of Class A shares have one vote per share.Footnote 8 As a result, the founder and CEO, Will Shu, had 57.5% of votes while only holding 6.3% of share capital immediately after the IPO.Footnote 9 Similarly to THG, Deliveroo can only apply for an admission to the LSE's Standard Listing Segment.

As is well known, choosing the standard listing instead of the premium listing makes THG's and Deliveroo's shares ineligible for inclusion in the FTSE UK Index Series.Footnote 10 This means passive funds, such as index funds and exchange-traded funds, cannot invest or trade their shares, which in turn compromises liquidity. Besides, not trading on the LSE Main Market's Premium Segment, which is deemed as London's gold standard listing regime, may further reduce the attractiveness of the shares and thereby increase the cost of capital. All these aspects do matter and may force potential issuers to choose other destinations to list their shares. Thus, the pressure on policymakers is also growing.

One year after the exploratory talks between the government and the investment industry on changing listing rules to lure new listings that might otherwise choose New York, Hong Kong or Singapore,Footnote 11 Chancellor Rishi Sunak formally launched the UK Listings Review, led by Lord Hill, in November 2020. The aim was to propose to lift bans over premium listing with dual class shares. The final report of the UK Listings Review also recommended, in March 2021, changing the exiting Listing Rules to allow dual class share structures for premium listings.Footnote 12

Resistance is, however, very much expected from institutional investors and the like. For example, the International Corporate Governance Network (ICGN), an organisation for institutional shareholders, expressed its strong opposition to dual class share structures immediately after the announcement of the Listings Review.Footnote 13 The Government Green Paper on ‘Building our Industrial Strategy’ has also noted that institutional investors and shareholder representative groups in the UK have opposed dual class share structures.Footnote 14

The dilemma faced by the policymakers is between closing the gap with other global financial centres to lure IPOs, on the one hand, and racing to the bottom regarding corporate governance standards, on the other hand. This paper endeavours to explore the potential future development of dual class share structures in the UK, in particular whether institutional shareholders could once again successfully oppose the use of dual class capitalisation in the institutionally dominated UK equities market. In order to achieve that, the paper will discuss the past trends of dual class listings in the UK and the current frictions, together with the experience and lessons from other global financial centres, such as Hong Kong and Singapore, in reforming their listing regimes to accommodate dual class IPOs. Contrary to the conventional view that permitting premium listings with dual class shares would compromise investor protection, this paper argues that the permission would actually enhance minority shareholder protection and shareholder engagement in the existing UK listing regime. If investor protection is the genuine concern of those who campaign against dual class shares, then allowing dual class listing in the Premium Segment would provide those inferior voting shareholders with better protection than they have now in the standard listing regime.Footnote 15

The remainder of the paper is organised as follows. Section 1 analyses the rise and fall of dual class share structures in the UK in the twentieth century to offer some historical background. Dual class shares, especially non-voting shares, arose as a takeover defence in the emerging hostile takeover markets. However, such structures were disliked and resisted by institutional investors. Due to the growing influence of institutional investment in the late twentieth century, dual class listing has been almost eliminated from the UK. Section 2 then looks into the current call for reinstating dual class listings on the LSE Main Market's Premium Segment. This section discusses the founders’ dilemma between retaining control and obtaining financial backing, and how dual class share structures can help founders to overcome the reluctance to go public. The corporate governance debate is critically examined in Section 3. The opposition to permitting dual class listings based on compromised investor protection and shareholder engagement is rebutted, because of the higher regulatory standards available in the premium listing regime. Additional safeguards are also discussed in this section as further reassurance. Section 4 examines the final report of the UK Listings Review and government responses. Together with the foregoing critical analysis, this section explores the potential future of dual class listings on the LSE. The final section concludes the paper.

1. Overview of dual class shares in the UK

(a) The historical path

Family-dominated firms were prevalent in UK public companies at the beginning of the twentieth centuryFootnote 16 and this continued until the mid-twentieth century.Footnote 17 Throughout the twentieth century, firms’ rapid growth and expansion was through acquiring other companies.Footnote 18 Facilitated by vibrant stock markets and takeover markets, equity issuance played an important role in funding these transactions. Accordingly, family ownership was diluted when issuing new shares to raise finance for acquisitions.Footnote 19 It is estimated that more than half of the dilution in the first half of the twentieth century was associated with share issuance for acquisitions.Footnote 20

All mergers and acquisitions that occurred between 1900 and 1950 were the result of an agreement between the merging companies, as the market for corporate control did not exist until 1953, when the first hostile takeover was launched.Footnote 21 Facing the emerging hostile takeover market and the threat of hostile takeovers, where the bidder could bypass negotiations with the target companies’ directors, companies started to seek protection and erect defences. Dual class shares, normally with voting shares given to insiders and non-voting or limited-voting shares sold to outside investors, were one of the important anti-takeover measures adopted at that time; the unequal voting rights arrangements helped to concentrate voting power into the hands of the family members, as the controlling party, and thereby make such dual class companies unlikely takeover targets.Footnote 22 For example, in 1965, about 15% of companies listed on the LSE had issued dual class shares with unequal voting rights.Footnote 23

However dual class shares, among other protective measures and takeover defences, did not last long due to the strong opposition of institutional investors. After studying the media coverage on dual class shares, Braggion and Giannetti found that there has been a ‘marked distaste’ and a ‘prejudice’ against the ‘undesirable practice’ of issuing non-voting or limited-voting shares by institutional investors since the late 1950s.Footnote 24 The rise of influential institutional investors in the 1960s and 1970s led to their ability to deny dual class share companies access to the capital markets. Companies were forced to unify dual class shares and abandon such share structures to cater for investor demand,Footnote 25 and dual class shares were virtually extinguished by the 1980s.Footnote 26

(b) The growing influence of institutional investors

The evolution of the ownership pattern in the UK is detailed elsewhere, so this paper does not intend to reiterate it. On the whole, the post-war punitive tax regime, where rates reached nearly 100% of investment income,Footnote 27 and the favourable tax regimes for the use of insurance policies and pension funds to participate in retirement saving schemesFootnote 28 and capital raising for mergers, provided incentives to unwind control.Footnote 29 It is generally agreed that the influence of institutional investors in British companies rose dramatically over the 1960s and 1970s. At the same time, family ownership had been largely displaced in the late twentieth century.Footnote 30

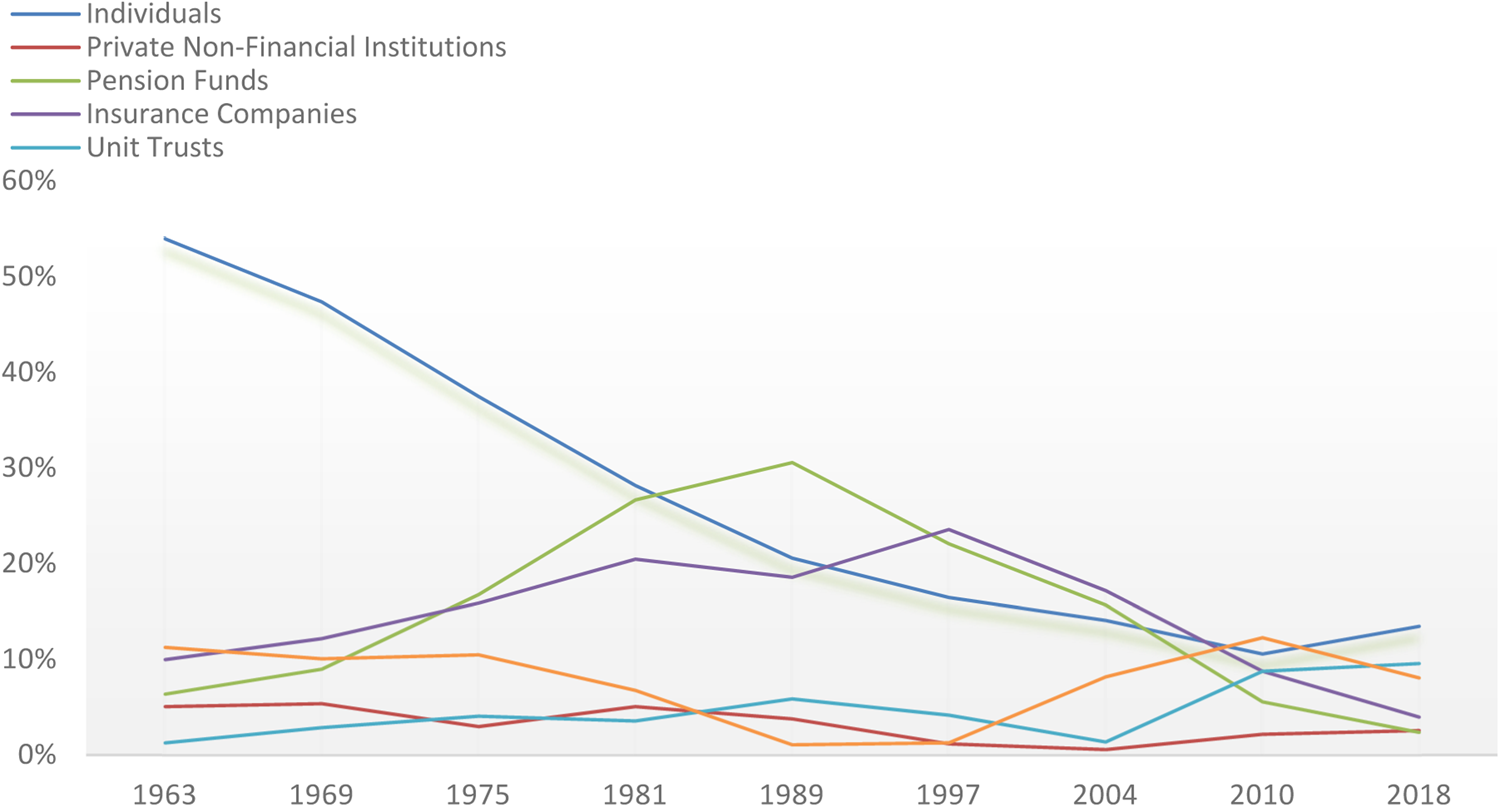

Figure 1. Share Ownership Change in the UK

Source: Office of National Statistics, Share Ownership time series dataset (2020)

Although a key feature of public companies in the UK, as in the US, is widely dispersed share ownership,Footnote 31 the UK equities market is more institutionally dominated than that of the US.Footnote 32 The 25 largest institutional shareholders held an absolute majority of the shares of many UK firms by the end of twentieth century.Footnote 33 Moreover, there are fewer regulatory barriers in the way of institutional shareholders’ communication in the UK, which can reduce the coordination costs and free-rider problems.Footnote 34 The governance provisions of the UK Companies Acts, the Corporate Governance Codes, the Takeover Codes and the Listing Rules all provide mechanisms for institutional investors to intervene in the management of investee companies.Footnote 35 Accordingly, another important feature of the UK corporate governance system is the ability of (semi) dispersed institutional shareholders, such as pension funds and insurance companies, to achieve a sufficient level of coordinated action to be able to influence the rule setting as well as the management of portfolio companies.Footnote 36 This helps British institutional investors largely overcome the collective action problem that has plagued American institutional investors and be significantly more active.Footnote 37 Among the many notable pro-shareholder changes institutional shareholders have contributed is the ‘opposition to non-voting, restricted voting or multiple-vote shares in favour of the principle of one share, one vote’.Footnote 38

The near extinction of dual class shares in the UK can be primarily attributed to the dominance of institutional investors.Footnote 39 Institutional investors were concerned about the interference of such share structures in the takeover process and the potential for management entrenchment. Unequal voting rights under dual class shares separate controlling shareholders’ voting rights from their cash flow rights and insulate them from the pressures of external investors and markets. Not surprisingly, institutional investors have sufficient incentive to resist unequal voting right arrangements, such as multiple voting shares or non-voting shares, and press for one vote per share. The low relative valuations of dual class firms compared to single class firms forced companies to abandon dual class capital structures in order to cater for investor demand.Footnote 40 By having an increasingly significant proportion of the shares, institutional investors in the UK equites market have successfully opposed dual class listings. As a result, while the UK has a very liberal regime, dual class IPOs are extremely unpopular. Thus, it was institutional investors that prevented companies from having dual class shares.

In fact, we can see that the Report of the Company Law Committee, led by Lord Jenkins in 1960s, was still in favour of the argument supporting voteless shares and concluded that the proposal to abolish non-voting shares was too drastic a step. The report recommended against legislative changes to impose a statutory requirement of one share, one vote.Footnote 41 Such a proportionate voting rule, requiring equity shares to carry voting rights proportional to their cash flow rights, was not mandated in the Listing Rules in the twentieth century either. However, British institutional investors exercised their market level influence by refusing to purchase shares with unequal voting rights, which led to companies with dual class shares being a rarity on the LSE, even though the UK had one of the most liberal regimes in this regard.Footnote 42

(c) One share, one vote for premium-listed companies

Entering the twenty-first century, facing continuous market pressure in connection with investor protection in companies with blockholders, especially the serious corporate governance problems posed by foreign companies who moved their primary listings to London in 2000s,Footnote 43 the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), the regulator of UK financial markets and the UK Listing Authority, had reinforced minority shareholder protection. Among many others, the Listing Rules were tightened to prevent artificial structures involving multiple classes with different voting powers, that would allow a small group of shareholders to exercise control.Footnote 44 With the intention of reinforcing minority shareholder protection, the FCA added the following two Premium Listing Principles relating to such restrictions.Footnote 45

Premium Listing Principle 3: All equity shares in a class that has been admitted to premium listing must carry an equal number of votes on any shareholder vote.

Premium Listing Principle 4: Where a listed company has more than one class of equity shares admitted to premium listing, the aggregate voting rights of the shares in each class should be broadly proportionate to the relative interests of those classes in the equity of the listed company.

This was the first time that the ‘one share, one vote’ principle became mandatory for all premium-listed issuers in the UK. This reflects a desire for a level playing field, concern about possible discrimination against minority shareholders associated with dual class shares, and fear of the potential exploitation of private benefits by controlling shareholders at the expense of the benefits of minority shareholders.

The Premium Listing Principles are applicable to issuers admitted to the LSE Main Market's Premium Segment and enforceable by the FCA. This means that while companies with differentiated voting rights arrangements are not eligible for the premium listing regime, companies with dual class structures are still eligible to apply for listing on the LSE Main Market's Standard Segment and Alternative Investment Market (AIM). The price for those choosing a dual class IPO in the UK is a ‘standard’ rather than ‘premium’ listing, meaning that the company will be subject to comparatively lower corporate governance standards and its listed shares cannot be included in the FTSE or bought by tracker funds.

2. The call to reinstate dual class shares

While dual class shares are now almost non-existent amongst listed companies in the UK, such structures have become increasingly popular elsewhere.Footnote 46 Considering the rising popularity of dual class IPOs, especially among high tech companies such as Google (now Alphabet) (2004), LinkedIn (2011), Facebook (2012), Alibaba Group (2014), Snap (2017), Dropbox (2018), and Zoom (2019), the UK cannot afford to lose out in the race to attract and host such sought-after companies. London needs to consider how it can remain one of the pre-eminent markets and lure technology start-ups away from New York, Hong Kong, Singapore and other financial centres. The UK Listing Review, led by Lord Hill, also aimed to close the gap with both the NASDAQ Stock Market (NASDAQ) and the Hong Kong Stock Exchange (HKEx). There is always a competitive pressure. For example, the Chairman of the Hong Kong Securities and Futures Commission said: ‘[allowing companies with dual class structures to list in Hong Kong] is a competition issue. It is not just the US – the UK and Singapore also want to attract technology and new economy companies to list. Hong Kong needs to play catch up’.Footnote 47

According to the EY Global IPO trends report, in 2020 there were 1,363 IPOs recorded worldwide but the LSE only recorded 30 IPOs.Footnote 48 London is ranked 12th by number of IPOs and only accounts for 2.2% of global IPOs.Footnote 49 Many of the largest technology companies have chosen dual class share structures to allow the founders to continue to retain some degree of control and to be insulated from the market for corporate control. Take the US for example: 13 out of 30 tech IPOs in 2018, 12 out of 40 tech IPOs in 2019 and 18 out of 42 tech IPOs in 2020 adopted dual class shares.Footnote 50 However, at the moment, the UK Listing Authority mandates that issuers with dual class shares cannot apply for ‘premium listing’.Footnote 51 As Lord Hill noted to the Chancellor, Rishi Sunak, easing restrictions over dual class listings is not a radical new departure to try to seize a competitive advantage; rather it is about ‘closing a gap which has opened up’.Footnote 52

(a) Fear of losing control and the long-term focus

Research finds that the key influencing factor in the listing decision is control, and fear of a loss of control is the most important reason for most unlisted companies to stay private.Footnote 53 During IPOs, founders’ equity holdings are diluted through the issuance of further shares, and their share of voting rights would fall accordingly under the one share, one vote principle. The loss of majority voting means they may lose the ability to determine the leadership of the firm. If the founders are involved in managing the company as directors and executives, they may be dismissed from leading the company by shareholders holding a simple majority of votes.Footnote 54 Noam Wasserman, an established Harvard Business School professor, has pointed out that in many cases founders gave up control of the board and the company in exchange for financial backing, while some entrepreneurs felt it was more important to maintain their ability to lead the business, even at the expense of increasing its value.Footnote 55 It is no wonder that founders with a strong desire for long-term control are reluctant to go public. In order to retain control, these companies may choose debt financing instead of equity financing. This will not only increase the costs of raising capital, but also restrict the access to capital markets for those pre-profit technology and innovative companies without a track record of profit making. In other words, some founders or entrepreneurs may choose to sacrifice fast growth by taking less money from outside equity investors in order to retain control.

Unsurprisingly, the fear of losing control of the company after an IPO is an important reason why UK tech-company founders are reluctant to list their companies.Footnote 56 While the UK is home to 17 tech unicorns, that is private and independent start-ups that are valued at over US$1 billion, such an emergence of privately-owned high-tech companies has not been reflected in tech IPOs.Footnote 57 Meanwhile, UK high-tech companies are disproportionately subjected to merger and acquisition activity compared with their international peers.Footnote 58 Many of the UK's privately-owned large high-tech companies (eg DeepMind) and LSE-listed high-tech companies (eg Worldpay) were eventually acquired by foreign companies.Footnote 59 The UK Listing Authority is also aware of the difficulty faced by early-stage science and technology companies and other scale-up companiesFootnote 60 in accessing capital in public markets.Footnote 61 In short, the UK public market fails to provide a stable or long-term home for UK technology companies.Footnote 62

The Oxera Report, commissioned by the European Union (EU), also strongly encourages flexibility in the use of dual class shares where national rules or practices prevent such share structures.Footnote 63 One suggested change, as acknowledged in the UK government's Industrial Strategy Green Paper, is to make it easier for companies to list with dual class share structures on the UK equities market.Footnote 64 This may benefit the UK tech industry specifically.

Permitting dual class listing on the LSE Main Market's Premium Segment could, however, help founders and entrepreneurs retain control while reaping the benefits of external equity financing.Footnote 65 The voting rights under dual class shares can be disproportionately greater than cash flow rights, so even if founders’ ownership stakes fall below 50%, they can still retain control via weighted voting rights.Footnote 66 The degree of control retained by founders with high voting power may help them overcome their reluctance to going public by insulating them from short-term market pressures.Footnote 67 This is particularly meaningful for technology companies, where visionary founders can maintain control of the company and create more value by implementing long-term projects without worrying unduly about near-term uncertainty and stock market performance. For example, the founders of Google defended their offering of dual class shares by arguing: ‘… outside pressures too often tempt companies to sacrifice long-term opportunities to meet quarterly market expectations. Sometimes this pressure has caused companies to manipulate financial results in order to “make their quarter”’.Footnote 68 Similarly, for THG, the prospect of relinquishing control was a major reason why its founder had previously been averse to going public.Footnote 69 The UK Government has also noted that unequal voting rights arrangements in favour of companies’ founders would allow them to focus more on long-term performance, and less on short-term market pressures.Footnote 70

(b) Recent dual class IPOs on the LSE

Furthermore, the recent dual class IPOs of THG and Deliveroo also bring focus back to the debate on dual class share structures in the UK context, regarding whether the premium listing regime should be reformed to cater for dual class listings. The special share acquired by Matthew Moulding, the founder and CEO of THG, provides him with the ability to pass or prevent the passing of any shareholder resolution after the IPO.Footnote 71 In fact, Moulding acknowledged that the US market was far more accommodating of capital structures that gave founders enhanced voting power and he told the Financial Times that ‘many people in our position would go and list in the US. The level of rights put in place there for myself and the business would be more material’.Footnote 72 Another high-profile dual class company, Deliveroo, also emphasised the ability of dual class structures to provide its founder and CEO, Will Shu, with the capacity to continue to execute on the long-term strategic vision to create long-term shareholder value after the IPO, while still allowing others to share in that growth.Footnote 73

Given THG's and Deliveroo's post-IPO market capitalisation, they would be included in the FTSE 100 if their shares were admitted to the Premium Segment. However, due to the bans on dual class shares in the premium listing regime, their shares can only be admitted to the Standard Segment. Put another way, it is notable that some technology companies are even willing to opt out of an important index in order to maintain their control via dual class share structures. It is argued that such share structures respond to the evolving reality of capital market structure.Footnote 74 Suffice it to say that the demand from tech-company founders to protect their ability to maintain control and the enthusiasm of the Government to attract more IPOs contribute to the growing call for dual class share structures, especially for high-tech and high-growth businesses in the premium listing regime.

3. The corporate governance debate

Faced with a call to reinstate dual class listings, the UK regulator could ease restrictions on dual class share structures as control-enhancing mechanisms, in order to encourage companies to list without owners having to relinquish control of their companies. London is eager to attract the most successful and innovative companies to list, especially in the aftermath of Brexit and in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic. There is also a clear policy goal to help UK markets to remain world leading and fit for the future shape of the economy, as reflected in the UK Listings Review launched at the end of 2020. The call to reinstate dual class share structures in the premium listing regime is essentially a call for more flexible capital structures to protect entrepreneurs’ idiosyncratic visions.Footnote 75 The dilemma for regulators is to balance investor protection with this increased demand for flexibility and competitiveness. While acknowledging the potential benefits of dual class listings, the UK regulator is worried about the potential erosion of the UK corporate governance standards.

In fact, investor protection – to strengthen minority shareholder protection in particular – was a key consideration when the UK listing authority mandated one share, one vote for premium-listed issuers in 2014.Footnote 76 It was believed that the unequal voting arrangement under dual class share structures would unfairly impinge upon (minority) shareholders’ rights and increase their risk of being abused.Footnote 77 However, if investor protection is the reason for rejecting dual class shares for premium-listed companies, then how can one justify permitting dual class listing on the Standard Segment, which may equally cause potential abuse of weighted voting power?Footnote 78 This section is therefore going to rebut criticisms that rely upon investor protection.

(a) (Institutional) Investors’ dilemma

Most technology and new economy companies are a potentially high-quality resource for listing.Footnote 79 If more of them can overcome their reluctance to go public, both the breadth and depth of capital markets would be consequently increased. Even though companies are currently permitted to list with dual class shares on the LSE Main Market's Standard Segment and AIM, shares of these companies would not be eligible for inclusion in the FTSE UK Index Series, which means index funds and other passive funds cannot trade them.Footnote 80 Therefore, relaxing the prohibition on premium listing with dual class shares would encourage more dual class listings, which in turn would provide UK public shareholders with more opportunities to take part in the success and growth of those companies.

While founders and entrepreneurial managers rarely want to cede control of their businesses, (institutional) investors will normally want to have some control over their future investment in most equity raisings. Permitting dual class listing would, however, reduce (institutional) investors’ influence on both the controlling party and the incumbent management. Thus, similar to the classic dilemma for founders, where on the one hand they have to raise resources in order to capitalise on the opportunities before them, but on the other they are reluctant to give up control over most decision making in order to attract investors, the dilemma for (institutional) investors is that on the one hand they want to share in the success of the fast-growth companies with dual class share structures and enjoy a high return, but on the other hand they are reluctant to relinquish their participatory rights.

Conventionally, shareholders’ voting power is the foundation for institutional shareholder engagement and monitoring, and it is tied to the economic returns on their shares. The decoupling of voting power from economic interests under dual class shares would cause the traditional ownership incentives to no longer work. In fact, this issue is twofold. First, the separation between voting rights and cash flow rights leads to the separation of ability and incentive to monitor: shareholders with weighted voting rights are able to discipline management, but may lack the financial incentive to do so; by contrast, shareholders with appropriate ownership incentives to monitor disloyal or ineffective managers may barely have the capability to effect a real change, due to their restricted voting power.Footnote 81 The decoupling of economic interest and voting power would systematically weaken the function of the market for corporate control.Footnote 82 Secondly, weighted voting rights under dual class shares would allow controlling shareholders to reduce their cash flow rights without affecting their lock on control. With a decline in the percentage of ownership stake, the costs of self-serving conduct would correspondingly decrease and the incentives to extract private benefits increase.Footnote 83 For example, a founder may choose the value-reducing action if their pro rata share of loss is smaller than their gain in private benefits, and dual class shares make it possible for a shareholder to retain full control with a very low shareholding.Footnote 84 The distorted incentives exacerbated by dual class shares are regarded as one of the main reasons for institutional investors’ resistance to such share structures and their prohibition in premium listings.Footnote 85

As a result, despite it being argued that the enhanced voting rights provided to founders of companies such as Google, Facebook and LinkedIn have contributed to their success by insulating founders from short-term market pressures, many institutional investors and shareholder representative groups have opposed dual class shares, arguing that they would weaken the UK's high standards of corporate governance and disadvantage minority shareholders.Footnote 86

(b) The rebuttal to the main criticism

The main criticism against the dual class share structures is that founders may use the disproportionate voting power provided by such structures to extract private benefits of control at the expense of minority shareholders or outside investors. This is the same situation that can occur in any company with controlling shareholders.Footnote 87 When the private benefit to a founder outweighs the costs he may bear from value-reducing actions, there will be adequate incentive for the founder to pursue such actions to the detriment of both minority shareholders and society as a whole.Footnote 88 Because the UK corporate governance system primarily targets arm's length investors,Footnote 89 the upset or frustration that can be caused by a controlling shareholder, either through holding a large block of equity or weighted voting rights, is understandable. However, it should be noted that companies in the UK are free to adopt dual class share structures, and eligible to apply for listing on the LSE Main Market's Standard Segment or Alternative Investment Market with such share structures. The right question to ask therefore becomes: will banning premium listings with dual class share structures help to improve minority shareholder protection?

The UK Listing Rules that apply to premium-listed companies require an applicant company to demonstrate that it will be carrying on an independent business as its main activity.Footnote 90 That is to say, for premium-listed companies with a controlling shareholder, they are mandatorily required to be independent from their controlling shareholders and function independently. As part of the independent business requirement, where a listing applicant has a controlling shareholderFootnote 91 upon admission, the Listing Rules mandate a written and legally binding relationship agreement between the controlling shareholder and the applicant, to ensure the controlling shareholder will conduct transactions and arrangements with its company at arm's length and on normal commercial terms, and not prevent the company from complying with its obligations under the Listing Rules or circumvent the proper application of those Rules.Footnote 92 Such undertakings in the relationship agreement with a controlling shareholder are required to be disclosed in the company's annual report.Footnote 93 If the undertakings of independence are not complied with by the controlling shareholder, the listed company must notify the FCA without delay,Footnote 94 and all transactions with the controlling shareholder will be subject to scrutiny regardless of the size of the transaction.Footnote 95 The FCA also reserves power to cancel the listing as an ultimate sanction for non-compliance with the Listing Rules.Footnote 96

A very common approach for shareholders to extract monetary benefits is to use related party transactions as an instrument for tunnelling, and the Listing Rules mandate strict scrutiny for such transactions or arrangements between a listed company and related parties.Footnote 97 The listed company is required to make a notification including the details of transaction, the related party and the nature and extent of the related party's interest in the transaction, and then to send related party circulars to shareholders.Footnote 98 Shareholder approval is required for related party transactions, and the listed company must also ensure the related party does not vote on the relevant resolution.Footnote 99

Another dramatic type of transaction, where a controlling shareholder may have a personal agenda that clashes with the interests of minority shareholders, is where they want to delist the company and take it private.Footnote 100 For cancellation of listing, there are also special rules designed to protect minority shareholders in companies with premium listings.Footnote 101 First, a special majority of not less than 75% of the votes is required for the resolution. And, secondly, if the company has a controlling shareholder, then a majority of the votes from independent shareholders is also required for the prior approval of the resolution.Footnote 102 Besides, independent directors are used to further ensure the accountability and protect the interest of the company as a whole. In a premium-listed company, the (re-)election of any independent director must be additionally approved by the non-controlling shareholders.Footnote 103

However, all the above requirements only apply to a company that has premium listing.Footnote 104 In other words, the Listing Rules relating to independent business requirements, relationship agreements with controlling shareholders, additional scrutiny and shareholder approval for significant transactions, related party transactions and cancellation of listing, among others, cannot protect minority shareholders in standard-listed companies. And the UK Corporate Governance Code will not be applied to these companies either. This means that companies admitted to the Standard Segment are subject to significantly lower obligations when compared with their counterparts in the Premium Segment. If the genuine concern is about shareholder protection, it would make more sense to permit dual class companies to list in the Premium Segment in order to impose higher corporate governance standards and provide a higher level of regulatory protection.

Take THG's IPO, for example. Its dual class share structure makes it ineligible to be listed in the Premium Segment. After the IPO, the founder is both the chairman and chief executive officer of THG,Footnote 105 he is also the indirect owner of the Propco Group, holding real estate used or occupied by THG under leases.Footnote 106 But because THG is not a premium-listed company, the principle relating to the division between the roles of chairman and chief executive in the UK Corporate Governance Code is not applicable, and THG is not required to explain any non-compliance in its annual report under the comply or explain approach.Footnote 107 Similarly, related party transactions (eg between THG and the Propco Group) will also be subject to less onerous scrutiny, as the relevant provisions in the Listing Rules are not applicable to companies with a standard listing.Footnote 108 If THG were allowed to be admitted to the Premium Segment, then a higher level of regulatory protection could be provided to investors.

Consequently, banning premium listing with dual class share structures per se will not help minority shareholder protection. Precluding companies with dual class shares from admittance to the premium listing regime, but allowing them into the standard listing regime with lower level of regulatory protection for minority shareholders, cannot be justified on the grounds of investor protection. Minority shareholder protection would be much better addressed by positioning shareholders with inferior voting power to use effectively the power available to them under the Listing Rules, rather than by precluding companies with dual class shares from listing in the Premium Segment. If mechanisms can be adopted to hold controlling shareholders accountable in companies with premium listings, the same mechanisms should also be able to help mitigate the risk of abuse by founders with multiple voting shares. For example, a listing applicant with dual class shares can be required to enter into a written and legally binding agreement with the holders of high voting shares, to ensure the latter would not prevent the applicant from complying with the Listing Rules or pursue self-interest at the expense of other investors. Related party transactions that are likely to lead to conflicts of interest would be subject to shareholder approval, and the related parties (ie those shareholders with weighted voting rights) would not be allowed to vote on the matter.

(c) Safeguards as further reassurance

As explained above, dual class listing or capitalisation is a way for founders to overcome the founder's dilemma of retaining control while obtaining external equity financing. This explains why such share structures are favoured by many high-growth and high-tech companies across the world. However, the UK regulator understandably needs more assurance in connection with investor protection, in spite of the empirical evidence showing better performance from dual class companies. In fact, as demonstrated in jurisdictions permitting and encouraging dual class listings, safeguards can be adopted to alleviate concerns over potential abuse of weighted voting rights as a corporate governance risk. First of all, regulators can adopt an enhanced voting mechanism. For matters relating to amendment of a company's constitution, merger, division, dissolution and other fundamental corporate changes, multiple voting shares can be limited to one vote each, regardless of their class, to constrain founders’ ability to exercise their weighted voting rights. Meanwhile, for the appointment and dismissal of independent directors and external auditors, changing the number of voting rights, and other matters that are likely to cause a conflict of interest, founders’ multiple voting shares can also be temporarily converted to single voting shares.Footnote 109 Such enhanced voting mechanisms can mitigate the potential abuse of power by shareholders with weighted voting rights and protect inferior voting shareholders by providing them with a say on important matters.

Another well-explored restriction on special voting shares is the sunset clause, which converts multiple voting shares into single voting shares.Footnote 110 Sunsets can be time-based, event-based or ownership-based.Footnote 111 Currently, the most common mandatory sunset provisions are event-based, where the sunset depends on the occurrence of a particular event. The design of sunset provisions is largely motivated by visionary founders’ or entrepreneurial managers’ belief in their ability to create more value by implementing a longer-term project without the fear of losing control.Footnote 112 When they can no longer lead or contribute to the management of the company, the justification of retaining their superclass of shares with disproportionately greater voting rights would disappear. The event normally includes the transfer of the multiple voting shares and the death, retirement or incapacity of the holders of such shares.Footnote 113

Thirdly, capping the maximum votes of the special voting shares can also serve as an effective means of constraining the divergence between the control and economic rights attached to them. For instance, the Singapore Listing Rules mandate that each multiple voting share shall not carry more than 10 votes per share.Footnote 114 The HKEx has a similar mandatory limitation on the ratio of high voting rights to low voting rights.Footnote 115 As the high-to-low voting ratio determines the fraction of equity shareholdings a controller needs in order to retain the control rights, the essence of limiting the maximal voting differential is to ensure founders’ ownership incentive through making them retain a higher percentage of equity shareholdings; this mitigates expropriation risks and better aligns founders’ interests with those of outside investors.Footnote 116

Fourthly, investor protection and managerial accountability under dual class share structures can also be checked by ensuring the independence of the board. For example, the Hong Kong Listing Rules mandate each listed dual class company to establish a corporate governance committee with independent non-executive directors to monitor the management of the company.Footnote 117 In Singapore, independent directors are required to constitute a majority of the audit, nominating and remuneration committees of dual class companies, and to serve as chairpersons of these board committees.Footnote 118 Thus, shareholders with inferior voting rights can be provided with the veto rights of electing independent directors, in order to increase the independence of the board from the controlling shareholders.Footnote 119 Last but not least, enhanced disclosure requirements that mandate information about the rationale for having such share structures, and the associated risks for non-controlling shareholders, can help to reduce outside investors’ costs of obtaining information relating to dual class share structures. This also allows them to better understand the risks associated with such share structures before making an informed investment decision.Footnote 120

In short, although dual class share structures may affect investors’ ability to participate in the internal governance of companies, such structures do not necessarily mean inadequate investor protection. Just as the agency costs between majority and minority shareholders in single class companies with controlling shareholders can be controlled, the potentially increased risks caused by dual class shares are by no means uncontrollable. After all, regulators are expected to combine high standards of regulation with flexibility. The foregoing discussion on mechanisms of enhanced voting, sunset, maximal voting differential, independent directors and disclosure outlines just some of the examples the UK regulator could consider adopting as further reassurance to investors and as a check on the exercising of founders’ weighted voting rights under dual class structures.Footnote 121

(d) Shareholder engagement

While institutional investors may have a continuing bias in favour of passivity, as concluded in the Myners Report,Footnote 122 the British government has been applying non-legislative pressures since the beginning of the twenty-first century. The Companies (Shareholders’ Rights) Regulations, Stewardship Codes, Corporate Governance Codes and various government consultations all aim to encourage shareholders to be more active and play a more important role in corporate governance, as it is believed that shareholder engagement could improve managerial accountability, including controlling excessive risk-taking. In particular, the UK Stewardship Code encourages institutional investors to exercise their stewardship responsibilities, including monitoring and engaging with companies on matters such as strategy, performance, risk, capital structure, and corporate governance, including culture and remuneration.Footnote 123 However, dual class share structures would help insulate management from direct (institutional) shareholder pressure and allow them the freedom to manage. If the UK regulator aims to encourage institutional activism and increase institutional shareholders’ impact on management, then permitting premium listings with dual class shares may have an impact on such a policy choice.

Again, the core of the question is not about whether dual class share structures would compromise shareholder engagement, as dual class companies are always allowed to list in the Standard Segment or AIM. It is, rather, about the impact of permitting dual class listing in the Premium Segment. As we can see from the discourse in Section 3(b) above, as long as dual class listing exists, permitting dual class companies to apply for premium listing will allow (institutional) shareholders to play a greater role in relation to approving related party transactions, cancellation of the listing, and (re-)election of independent directors among other things. In other words, unless (institutional) shareholders decide not to invest into dual class companies at all, allowing these companies to list in the Premium Segment will only provide minority shareholders (ie shareholders with inferior voting rights in the context of dual class companies) with more chances to engage, compared with solely allowing companies with dual class shares to be admitted to the Standard Segment. Further, enhanced voting processes and other mechanisms as explored in Section 3(c) above would also ensure (institutional) shareholders’ participatory rights relating fundamental corporate changes or matters that are most likely to cause conflicts of interest.

The UK's Companies Act 2006 also offers minority shareholders means to intervene when the company is not being run in a way that benefits all shareholders. When directors breach their duty to promote the success of the companyFootnote 124 or other fiduciary duties by managing the company for the personal benefit of founders with weighted voting rights,Footnote 125 minority shareholders can seek to obtain leave from the court to initiate a derivative claim on the company's behalf if the board decides not to pursue the wrongdoer.Footnote 126 Section 994 of the Companies Act 2006 also empowers a court to grant relief where a company's affairs have been conducted in a manner that is unfairly prejudicial to the interest of the minority shareholder. As acutely pointed out by Cheffins, the unfair prejudice under section 994 could also help to facilitate the enforcement of a relationship agreement with the controlling shareholder.Footnote 127 Accordingly, if stricter obligations can be imposed upon companies, this would potentially provide more grounds for minority shareholders to apply for relief under the Companies Act 2006. Thus, permitting dual class companies to be admitted to the Premium Segment, with its higher level of regulatory requirements, could enhance, rather than diminish, shareholders’ engagement in dual class companies.

4. Future development and policy recommendations

Flexibility of capital structure and the multiple paths entrepreneurs can take to public markets are seen as central to cultivating entrepreneurship and innovation, one of America's greatest strengths.Footnote 128 As declared by the NASDAQ, dual class structures allow investors to invest side-by-side with innovators and high growth companies, enjoying the financial benefits of these companies’ success.Footnote 129 The Kalifa Review of UK FinTech also highlighted the important role of dual class shares in improving the UK listing environment in order to reinvigorate the fintech sector, to drive growth and innovation.Footnote 130

As is well known, UK company law intentionally leaves the affairs of internal corporate management to the company itself and remains silent on many areas of corporate decision-making.Footnote 131 It supports the private ordering of corporate governance arrangements, including dual class shares.Footnote 132 The right question to ask is: will admitting dual class companies to the Premium Segment compromise minority shareholder protection in the existing UK listing regime? The main objection to such permission is based on investor protection and shareholder engagement, and this has already been critically examined and rebutted in Section 3 above. The higher corporate governance standards and regulatory requirements in the premium listing regime can offer more protection to minority shareholders than they currently enjoy in dual class companies in the Standard Segment.

(a) Lord Hill's report

Once the UK regulator's concern over maintaining high governance standards and investor protection has been appropriately addressed, there will be no further reason to continue banning premium listings with dual class share structures.Footnote 133 Just as many other developed economies that have started and/or continue to support dual class share structures, the UK is also attempting to follow this trend in order to make London a more attractive place for entrepreneurs to take companies public. Lord Hill's report highlights the importance of dual class listings and recommends changes in the Listing Rules in order to allow companies with dual class share structures to list on the LSE Main Market's Premium Segment.Footnote 134 Following the UK Listings Review, Lord Hill's report also identifies four key concerns: (1) conversion/termination; (2) sunset provisions; (3) (ratio of) voting rights; (4) scope of rights attached to Class B shares.Footnote 135 The first issue concerns when special voting shares will convert into ordinary voting shares on transfer, a classic event-based sunset scenario.Footnote 136 The second concern is about the time-based sunset. The third is about maximal voting difference between special and ordinary voting shares. The fourth concern is about the constraint over controllers’ ability to exercise their weighted voting rights on certain issues, such as fundamental corporate changes or matters that are most likely to cause conflicts of interest.

Accordingly, Lord Hill's report proposes five conditions to allow dual class share structures for companies into the LSE's premium listing regime: (1) a maximum duration of five years; (2) a maximum weighted voting ratio of 20:1; (3) requiring holder(s) of B class shares to be a director of the company; (4) voting matters being limited to ensuring the holder(s) are able to continue as a director and able to block a change of control of the company while the DCSS (dual class share structure) is in force; and (5) limitations on transfer of the B class shares.Footnote 137 These conditions are essentially safeguarding measures that aim to constrain the holders of weighted voting power while allowing dual class companies to be admitted to the Premium Segment. They are not materially different from the safeguards discussed in Section 3(c) above, with the exception of the time-based sunset provision.Footnote 138

(b) An optimistic future for dual class listing in the UK

It is, however, important to note that regulations alone cannot explain the rise and fall of dual class share structures. The absence of dual class listings in the UK is largely attributed to institutional investors’ opposition,Footnote 139 and IPOs will not proceed or succeed without institutional investors’ support. Shares are legal property in their own right,Footnote 140 which can be described in terms of their cash flow rights and voting rights.Footnote 141 The cash flow rights, such as rights to receive dividends, are economic rights that would not be directly affected by unequal voting rights arrangements.Footnote 142 By contrast, the voting rights, namely the governance rights, would be affected by such share structures. Accordingly, it is crucial to know whether UK institutional shareholders care about their governance rights.

While shareholder-friendly governance arrangements and fewer barriers in the way of shareholder coordination in the UK, as discussed in Section 1(b) above, may favour institutional shareholder activism, the domestic institutions have shifted a significant proportion of their equity investments out of the UK (holding more overseas equities than domestic equities) after the removal of restrictions on capital movements.Footnote 143 Non-UK institutional investors now hold half of the shares in the UK equities market.Footnote 144 The change in the composition of the institutional shareholder body brings the question of whether overseas institutional investors also have a high commitment to equity investment and shareholder engagement. Alongside incentives for institutional activism, there are also strong disincentives for them to act, including the belief in competitive market pressures and incentives, bias against getting ‘locked in’, costs and inconvenience of intervention, the ‘race to the exit’, insufficient resources and expertise, and the fear of government intervention.Footnote 145 This is why Paul Davies concluded that ‘it was clear that institutions often felt that the incentives not to intervene outweighed the incentives to do so’.Footnote 146 As a result, UK institutional investors rarely intervene to change management unless there are serious doubts about the integrity or competence of the incumbent management.Footnote 147 In other words, such interventions remain ‘defensive’ in orientation.Footnote 148

Meanwhile, the rise of index funds and exchange-traded funds, which are designed to automatically track a market index and match its performance, also highlights that most investors are weakly motivated voters and will rarely use their voting power to participate in corporate governance.Footnote 149 While the UK's shift from active to passive investment strategies is modest compared to the unprecedented shift in the US,Footnote 150 there has been a steady rise in inflows to passive funds in the UK. Although passive funds do not yet dominate the UK markets,Footnote 151 the proportion of passive funds in the UK asset management market has increased from 11% in 2015 to 28.6% in 2020.Footnote 152 Accordingly, there are reasons to suspect that institutional shareholders’ opposition to dual class listings is more an issue of psychological impact than governance impact.Footnote 153 If this is the case, then merely improving investor protection will not substantially change UK institutional investors’ traditional distaste for dual class shares.Footnote 154

While the success of dual class share structures relies upon market acceptance, institutional investors’ permission should not become the prerequisite for relaxing premium listings with dual class shares on the LSE. On the grounds that institutional investors have the freedom to choose not to buy shares with unequal voting rights, or to bargain for a discounted price after taking into account their reduced ability to control the management, decisions for issuers to adopt dual class structures should be a choice of private ordering of corporate governance arrangements. Private ordering allows individual companies’ internal affairs to be tailored to their own attributes and qualities.Footnote 155 Investors will buy shares only when they estimate that the value of the governance and economic rights they carry equals or exceeds their price.Footnote 156 On the other side, founders and entrepreneurs, as the controlling parties, would bear the cost of dual class shares.Footnote 157 When investors are adequately informed about the potential risks associated with unequal voting shares, these factors will be incorporated into their price, facilitated by competition for funding in public markets.Footnote 158 In other words, investors would be compensated for their reduced ability to control management by demanding a higher return. This means founders and entrepreneurs have to sacrifice a higher valuation for more control when the investors pay a fair price for inferior voting shares. Thus, in theory, the cost would be borne by the founders and inferior voting shares would not harm external investors.Footnote 159

In fact, UK company law enables private ordering and the issuance of shares with unequal voting rights by providing default, not mandatory, rules. Once the UK regulator can be satisfied with the additional protection for inferior voting shareholders via various safeguarding measures, the bans over dual class share structures in the Premium Segment should be released to allow individual companies and investors to make their optimal governance and voting arrangements. There would be no social need to constrain the choice of such share structures.Footnote 160 For example, the near extinction of dual class share structures in the UK in the late twentieth century vividly demonstrates how investors can constrain such choice.

The LSE has backed these relaxations on the use of dual class shares.Footnote 161 The FCA, as the UK Listing Authority, also welcomes Lord Hill's report for the UK Listings Review.Footnote 162 The FCA has committed to act quickly with the aim of publishing a consultation paper by the summer and seeks to make relevant rules (subject to consultation feedback and FCA Board approval) by late 2021.Footnote 163 The UK Government also welcomes Lord Hill's report and is committed to ensuring that the UK's markets are as competitive as possible, by supporting flexible capital structures to meet the needs of many different companies.Footnote 164 Thus it is very likely that bans over dual class listing on the LSE Main Market's Premium Segment will be lifted by the FCA when new rules are made later this year, and it can be expected that more technology companies will choose London to go public.Footnote 165

Last but not least, it should also be noted that strict safeguarding measures will restrain the founders’ exercise of weighted voting rights, and hence deter the willingness of potential entrepreneurs to go public with such share structures.Footnote 166 They may be forced to choose other, less stringent, jurisdictions as a destination for dual class IPOs.Footnote 167 For example, Grab Holdings Inc, a Singapore-headquartered ride-hailing to delivery giant in Southeast Asia, avoided a primary listing on the Singapore Stock Exchange but chose a NASDAQ listing via a US$40 billion merger with a special purpose acquisition company (SPAC).Footnote 168 Its co-founder and CEO, Anthony Tan, obtained 60.4% of the voting power while owning a stake of just 2.2% after the listing.Footnote 169 Apparently, the maximal voting difference contained in the revised Singapore Listing Rules cannot accommodate the level of control Tan desired.Footnote 170 When the high/low voting ratio is 10:1, Tan is required to hold 9.1% of shares in order to retain majority control over the company.Footnote 171 As he desired a much smaller equity stake, it is unsurprising that NASDAQ, which has much less rigorous rules on dual class shares, was chosen as a destination. In short, if the ultimate goal of permitting dual class shares in the premium listing regime is to boost the flexibility of UK capital markets and attract/retain innovative and high-technology companies to list in London, and to compete with the other international financial hubs, as suggested by the Kalifa Review of UK FinTech and Hill's UK Listings Review, then the proposed safeguards following the permission should also be very carefully considered and balanced.

Conclusion

Dual class share structures emerged as protective defences against the threat of hostile takeover in the UK in the mid-twentieth century. Such share structures typically include two or more classes of ordinary shares carrying unequal voting rights at general meetings, so they are chosen by controlling shareholders (eg founders) to retain control without having to bear excessive cash flow risk.Footnote 172 With the rise of institutional investors in the late twentieth century and their opposition to dual class capitalisation, dual class IPOs become increasingly unpopular and companies with dual class shares become almost extinct on the LSE. Moreover, the ban over premium listings with dual class shares on the LSE has effectively made London an international bastion of the one share, one vote principle.

However, in addition to some efficiency-based reasons for choosing dual-class structures,Footnote 173 this paper finds that permitting dual class listings on the LSE Main Market's Premium Segment would indeed make more sense regarding investor protection and engagement. Companies admitted with premium listings will have more onerous continuing obligations imposed on them than their counterparts in the Standard Segment, which would in turn provide a higher level of regulatory protection for minority shareholders and more opportunities for them to engage. More importantly, investors, and especially institutional investors, can bargain and evaluate the price of inferior voting shares. The near extinction of dual class listings in the UK in the late twentieth century provides a good example that the private ordering of voting rights, among other corporate governance arrangements, will lead to desired outcomes. A company intending to list with a dual class share structure should trade off the cost and the benefit of such a structure. As long as the investors pay a fair price for inferior voting shares when their limited ability to influence management is taken into account, the controlling party bears the potential cost, such as a low valuation. This can be further facilitated by the enhanced disclosure mechanism.Footnote 174 In short, there is no need to constrain the choice of individual companies’ capital structures or voting right arrangements, since they would be constrained by the market.

The recent revival of dual class share structures has been fuelled by tech-company founders favouring them around the world. Competitive pressure is also pushing UK policymakers to relax the limits on such share structures in order to lure more tech IPOs and strengthen London's position as a leading financial centre. Not surprisingly, Lord Hill's report on the UK Listings Review has recommended allowing companies with dual class share structures to list in the Premium Listing Segment.Footnote 175 This move is welcomed by the LSE, FCA and Government. It is therefore reasonable to foresee that the FCA will permit dual class listings in the premium listing regime, accompanied by safeguards, in the near future. Of course, this will not be the end of the debate over dual class share structures in the UK. Institutional investors will continue to oppose such a share structure, but the battleground will soon be shifted from assessing the desirability or permissibility of such dual class structures to how to safeguard holders of inferior voting shares.