The importance of the humble congregational hymn tune to Ralph Vaughan Williams’s music and musical philosophy is well known. Recognizing that church attendance represented the only regular opportunity most people had for music-making, he set aside his own theological scruples to focus on this crucial genre of amateur singing.Footnote 1 He devoted the better part of two years’ labour to the editorship, with Percy Dearmer, of The English Hymnal (1906, rev. 1933; henceforth EH) and went on to edit, with Dearmer and Martin Shaw, another important volume of congregational song, Songs of Praise (1925, enlarged 1931; henceforth SoP and SoPE).Footnote 2 In these and related publications, Vaughan Williams personally arranged upwards of two hundred tunes — many of them folk songs — and likely adapted or tweaked existing arrangements of hundreds more.Footnote 3 He also incorporated well-known hymn and psalm tunes into his original compositions, notably the operas Hugh the Drover and The Pilgrim’s Progress. The celebrated Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis is founded on a psalm tune by Tallis published in 1567.

Of course, Vaughan Williams did not merely adapt existing melodies in crafting hymn tunes but also composed his own. Some of these — sine nomine (‘For All the Saints’), salve feste dies (‘Hail Thee, Festival Day!’), and down ampney (‘Come Down, O Love Divine’) — are among the best known of the twentieth century and occupy a secure place in the repertories of Catholic and Reformed congregations alike. Michael Kennedy views these ‘great original hymns’, all written for the 1906 EH, as among the fruits of Vaughan Williams’s first maturity, one in which the ‘liberating influence’ of hymnody played a central role.Footnote 4 For Erik Routley, the slightly less famous tunes of SoP matter even more: these ‘experiments of a highly progressive sort’ marked a new seriousness in writing for congregations and ‘made musicians look at a hymnal for the first time with respect’.Footnote 5

Yet despite the recognized importance of Vaughan Williams’s engagement with hymnody, and the prominence of specific tunes written by him, there is currently no accurate works list of his original hymn tunes. Table 1 illustrates the problem. The first column lists the twenty-seven tunes that have variously been suggested for the distinction, while the second column provides a chronological list of the thirteen publications in which those tunes first appeared. At the head of columns 3 to 10 are eight key publications that itemize Vaughan Williams’s original hymn tunes, with Xs placed below to indicate the tunes selected in each case. A final column offers my own proposed inventory. A quick perusal of these columns shows uniform (or near-uniform) agreement on fifteen of the tunes, but notable divergence on the other twelve. Indeed, the final totals (given in the bottom row) fluctuate markedly. Even authors who agree on the number of Vaughan Williams originals arrive at that figure by different means.

Table 1. Vaughan Williams’s original hymn tunes as given by various commentators, 1950–2022*

| Tune Name | Place of first publication | Foss (1950) |

Kennedy (1964/1996) | Ottaway(1980) | Butterworth(1990) | Day(1998) | Barr(2004) | Hoch(2020) | Saylor(2022) | Onderdonk(proposed) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. DOWN AMPNEY | The English Hymnal (1906); all tunes reprinted in Songs of Praise and Songs of Praise Enlarged | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| 2. RANDOLPH | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| 3. SALVE FESTE DIES | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| 4. SINE NOMINE | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| 5. ALMA CHORUS | The New Office Hymn Book (1908) | X | ||||||||

| 6. TRIUMPHE! PLAUDANT MARIA | X | |||||||||

| 7. FAMOUS MEN (canticle) | Printed separately as ‘Let Us Now Praise Famous Men’ by Curwen (1923); later reprinted in Songs of Praise Enlarged | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| 8. CUMNOR | Songs of Praise (1925); all tunes reprinted in Songs of Praise Enlarged | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| 9. GUILDFORD | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| 10. KING’S WESTON | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| 11. MAGDA | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| 12. OAKLEY | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| 13. ‘Wither’s Rocking Hymn’ | The Oxford Book of Carols (1928) | X | X | |||||||

| 14. ‘Blake’s Cradle Song’ | X | X | ||||||||

| 15. ‘The Golden Carol’ | X | X | ||||||||

| 16. ‘Snow in the Street’ | X | X | ||||||||

| 17. MARATHON | Songs of Praise for Boys and Girls (1929); later in Songs of Praise Enlarged | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| 18. ABINGER | Songs of Praise Enlarged (1931) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| 19. COBBOLD (w/ Martin Shaw) | X | |||||||||

| 20. MANTEGNA | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| 21. WHITE GATES | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| 22. LITTLE CLOISTER | Printed separately by OUP (1935) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| 23. My Soul Praise the Lord | Printed separately by SPCK (1935); reprinted separately by OUP (1947) | X | X | X | ||||||

| 24. ‘A Hymn of Freedom’ | The Daily Telegraph, 20 Dec. 1939; later as No. 1 of Five Wartime Hymns (1942) | X | X | X | ||||||

| 25. ‘A Call to the Free Nations’ | Printed separately by OUP (1941); later as No. 2 of Five Wartime Hymns (1942) | X | X | X | ||||||

| 26. ‘The Airmen’s Hymn’ | Printed separately by OUP (1942) | X | ||||||||

| 27. ST MARGARET | Hymnal for Scotland (1950) | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Totals: | 14 | 23 | 14 | 20 | 15 | 19 | 15 | 16 | 19 |

* The commentators and sources of these lists are Hubert Foss, Ralph Vaughan Williams: A Study (George G. Harrap, 1950), p. 210; Michael Kennedy, A Catalogue of the Works of Ralph Vaughan Williams, 2nd edn (Oxford University Press, 1996), pp. 314–15, which duplicates in essentials the information given in Kennedy, The Works of Ralph Vaughan Williams (Oxford University Press, 1964), pp. 752–53; Hugh Ottaway, ‘Ralph Vaughan Williams — Works’, in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, ed. by Stanley Sadie (Oxford University Press, 1980), xix, pp. 578–79; Neil Butterworth, Ralph Vaughan Williams: A Guide to Research (Garland Publishing, 1990), pp. 78–89; James Day, Vaughan Williams, 3rd edn (Oxford University Press, 1998), pp. 296–97, 311, and 314–15; John Barr, ‘Determining a Chronological List of RVW’s Original Hymn Tunes’, in Journal of the Ralph Vaughan Williams Society, 29 (2004), pp. 16–17; Matthew Hoch, ‘Vaughan Williams and the Hymnals: An American Perspective’, in Ralph Vaughan Williams Society Journal, 79 (2020), pp. 8–11; Eric Saylor, Vaughan Williams (Oxford University Press, 2022), pp. 266, 274, and 276–79.

There are good reasons for this. The most obvious is that two Vaughan Williams originals — alma chorus and triumphe! plaudant maria (nos. 5 and 6 in column 1) — have hitherto been unknown to Vaughan Williams commentators: my column at the far right of Table 1 is the only one to include them. Another hymn tune unique to my inventory, cobbold (no. 19), is known to most commentators but has been mistakenly identified by them as an arrangement of another composer’s tune. I will return to these works at the very end of this essay.

Another reason for discrepancy is the fact that compiling a specialized listing of this sort has not been a priority for Vaughan Williams scholars. Of the ten inventories appearing in Table 1, only three — Barr’s, Hoch’s, and my own — have been compiled with hymn tunes specifically in mind. The other six come from larger cataloguing projects focused on Vaughan Williams’s oeuvre as a whole, and these, naturally, have not always focused on the details needed for a study of this kind. Still, authors’ opinions on most items can reasonably be ascertained by cross-checking various catalogue entries, though some ambiguities and uncertainties necessarily persist. Table 1 reflects my interpretive conclusions.Footnote 6

Not that a ‘perfect’ interpretation, were that even possible, would result in a uniform list. This is the third and most significant reason for divergence — the fact that not all commentators agree on the criteria that make for a congregational hymn tune, or if they do, they have not applied them consistently. This, too, is not surprising. Hymn tunes can be elusive, with widely varied layouts, source materials, and performance styles. Just within the relatively circumscribed history of Anglican hymnody, the tradition Vaughan Williams was working in, we see enormous shifts: from the Calvinist-inspired a cappella singing of metrical psalms in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, through the disparate performance styles of eighteenth-century ‘lining out’ and ‘west gallery music’, to the rising aspirations for ‘artistic’ church music in the Victorian period. In this last stage, the reintroduction of choirs and organs prompted the absorption into hymnody of everything from opera arias and oratorio choruses to traditional folk and carol melodies.Footnote 7 Even if we assume that scholars are using a standard definition of the genre — one where a hymn tune is 1) a stand-alone composition, with 2) a repeating strophic melody, 3) set to multiple verses of 4) a religious metrical poem, 5) specifically written for musically untrained congregations to sing, as 6) an aid to their Christian worshipFootnote 8 —exceptions have still crept in. Thus does Nicholas Temperley, in his catalogue of English-language hymns published before 1820, admit non-strophic fuguing tunes and highly elaborate (that is, clearly non-congregational) polyphonic psalm settings even as he explicitly endorses the definition given above.Footnote 9 Vaughan Williams commentators have been similarly inconsistent. Rightly emphasizing the primacy of the congregation in hymn-singing, they nonetheless include tunes lying beyond the musical abilities of the average church-goer. Correctly stressing the worship component of hymnody, they admit at least one tune whose text actually lacks religious content. The inconsistency goes the other way as well — as when the same worship criterion results in the rejection of tunes intended for sacred venues, if at one remove. Focusing unduly on hymn books, too, commentators reject perfectly good examples originating in other sources.

Again, hymn tunes are tricky: the shifting material and social conditions in which they are obtained and performed means that identifying them is harder than meets the eye. However, unless we wish to abandon any serious effort at classification and effectively accept all the items in Column 1 as hymn tunes, we need to attempt an ‘objective’ reckoning based on the six established criteria outlined above. The results may surprise (as is perhaps already observable from the Table, where in two cases my conclusions disrupt previous unanimity). Still, the consistent application of settled criteria should keep the exceptions to a minimum while also providing the tools to assess borderline cases. These last are especially crucial, for it’s the borderline works that bring us into contact with regions rarely encountered in discussions of Vaughan Williams’s hymn tunes — their links with school and community music, for example, and their often messy overlap with other genres, notably the unison song, the carol, and the hymn-anthem. Such ‘entanglements’ were in fact central concerns of church composers between 1900 and 1940, and in bringing them to the fore, the proposed approach greatly enriches our historical understanding of the composer.

The methodology also sheds light on Vaughan Williams’s aesthetics and core beliefs. As we might expect from this outstanding advocate of amateur music and musicians, the congregational element was for him paramount, the goal always to encourage the musically inexperienced church-goer to sing with confidence.Footnote 10 What the strict application of the criteria helps to show is just how many different ways he went about doing this. His main challenge was how to handle the choir, that unmovable legacy of nineteenth-century worship whose own traditions of musical elaboration and artistic presentation threatened to undermine a congregational emphasis. His solutions were ingenious and involved the tweaking of inherited performance styles as well as the development of new ones. Always, though, flexibility was the rule, and he drew on different notational layouts to meet every performance situation. These layouts (labelled A to E) will figure prominently in the discussion that follows. They help elucidate another surprising outcome of this investigation: that in creating his original hymn tunes, Vaughan Williams embraced and refined the practices of Victorian hymnody as much as he rejected them.

The survey begins by considering Vaughan Williams’s first hymn tunes for the 1906 EH, but quickly pursues a topical approach by focusing on the intense congregational aesthetic of SoP and the development of the unison hymn tune. Attention eventually returns to the EH as the essay explores the composer’s varied handling of the choir. Throughout, the investigation intermittently seeks to ‘fill out’ the works list, when discussing both relatively unproblematic items and the more difficult borderline cases that lie at the heart of the essay.

*

Of course, ‘congregational ability’ was on Vaughan Williams’s mind from the start. He undertook to edit the EH in part because he was concerned that the trained choir, already so central to Victorian patterns of worship, was encroaching on hymn-singing, traditionally the domain of the congregation. He responded by pitching hymn tunes as low as possible, introducing slower tempi, and insisting that ‘the congregation must always sing the melody and the melody only’.Footnote 11 What he sought in this last point especially was to encourage congregational involvement by simplifying their role. The elaborate four-part SATB harmony typically encountered in Victorian hymns, whether played by the organ or sung by the choir (or, in churches using the full music edition, seen in the hymn book itself), had the potential to confuse — and ultimately silence — these inexperienced singers. In this, he was responding to two interrelated developments around 1900: the ‘congregationalist’ campaign (ultimately Anglo-Catholic in origin, with roots in the Oxford movement of the mid-nineteenth century) to reverse the power imbalance between trained choir and amateur congregation in worship services, and second, the reaction in taste to the ‘syrupy’ chromaticism and sentimentality of Victorian hymnody.Footnote 12 Given these concerns, ‘fine melody rather than the exploitation of a trained choir’ (as Vaughan Williams put it) was the goal,Footnote 13 and unison congregational singing, along with an unvarying strophic musical structure, was essential to keep the inexperienced church-goer engaged and on task.

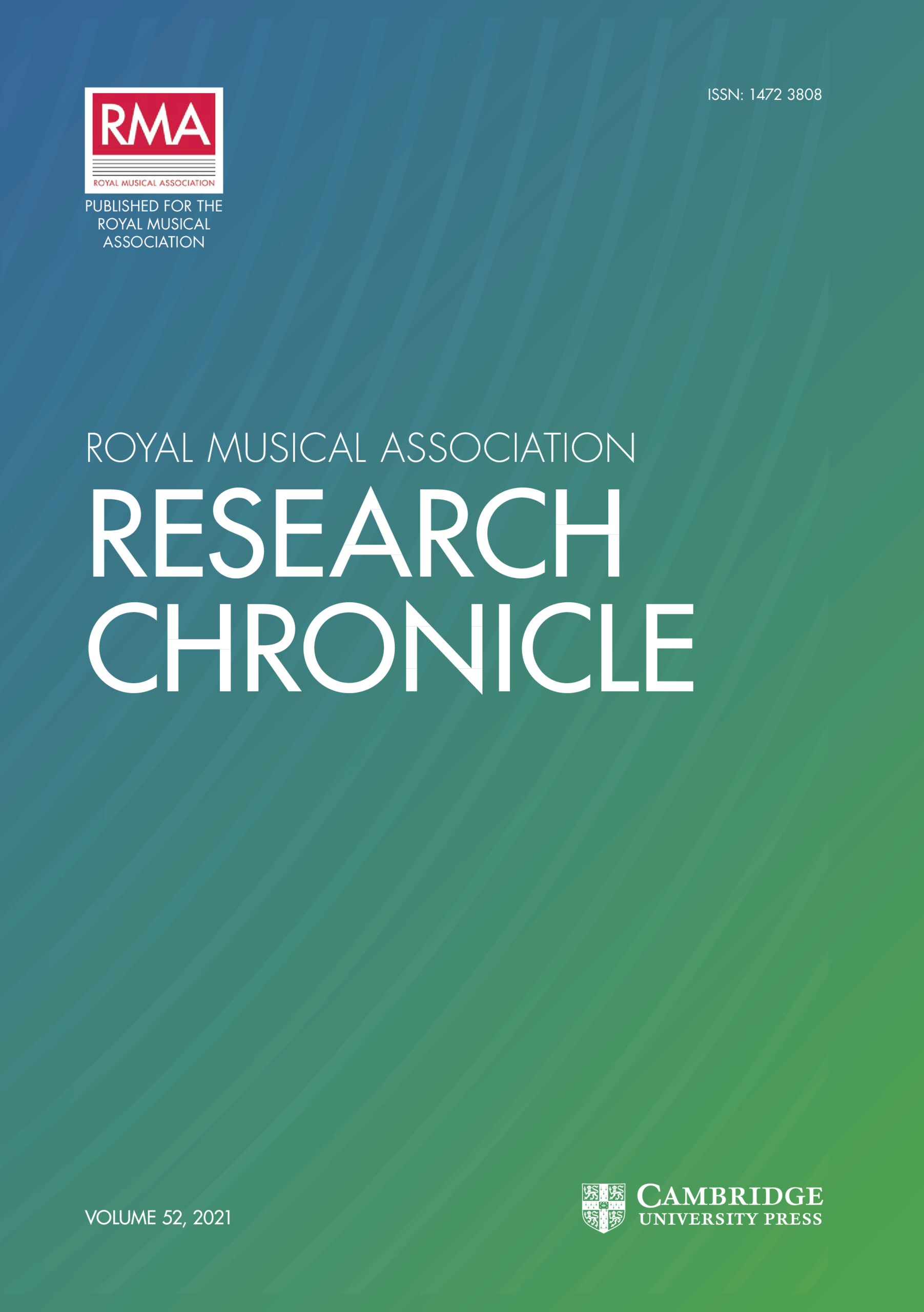

Both requirements anchor the celebrated down ampney, first published in the 1906 EH (where it appears as no. 152) though subsequently reprinted in many other hymnals. (See Example 1.) This is indeed a proper hymn tune — it meets all six criteria outlined above — but its somewhat meandering melody and elaborate part-writing (and striking chromaticism at the join between its fourth and fifth phrases) bring it close to the Victorian examples the composer deplored. Even its formatting, four-voice SATB harmony with no performance direction given (what I call Layout A), resembles the norms established in Victorian hymn books. But again, the injunction in the EH preface that the congregation is to sing the melody only mitigates these complexities, focusing the congregation’s attention on a tune whose lyrical beauty becomes ever more apparent with every strophic repetition. (The supportive organ part, where the melody appears in the top voice, contributes hugely to this as well, of course.)Footnote 14 Five other Vaughan Williams originals use Layout A (listed in the Appendix), but only magda has approached down ampney in popularity.

Example 1. DOWN AMPNEY (‘Come Down, O Love Divine’), no. 152 from The English Hymnal (1906) [Layout A].

With the turn to Layouts B, C, and D in SoP and SoPE, however, the composer as champion of the ordinary church-goer emerges in full force. These layouts mark three different, if closely related, ways to notate the so-called ‘unison hymn tune’, a new type of tune emerging around 1900 where all voices, congregation and choir, are specifically instructed to sing the melody line only.Footnote 15 This kind of tune likewise grew out of the congregationalist campaign and the associated reaction to Victorian harmony described earlier, but it goes one better than Layout A tunes in its level of congregational support. Here, the choir joining in with the people on the melody line lends encouragement well beyond what the organ and SATB choir might do. It’s unclear just why Vaughan Williams fussed with the three separate layouts, given that they all amount to the same performance practice and have a similar sonic result. Possibly B and C had the advantage of familiarity, since to outward appearances they resemble the ‘traditional’ two-staved Victorian hymn (though C, as noted, allowed for a more idiomatic organ part).Footnote 16 The same rationale may also explain why king’s weston (‘At the Name of Jesus’) and marathon, though initially appearing in the three-staved Layout D in SoP and SoP for Boys and Girls (1929), respectively, were later recast in two staves (Layout C) for SoPE. (See Examples 2a and b, which, for clarity, reverse this chronology and present king’s weston first in Layout C (from SoPE) and then in Layout D (from SoP).) What is clear, and significant, however, is that the majority of Vaughan Williams’s original hymn tunes — eleven of the nineteen total — are of this unison type. The choir joining in on the people’s part not only gave great vocal encouragement but, in effect, raised the status of the congregation above that of the choir by relegating the latter to a merely supportive role.

Example 2a. KING’S WESTON (‘At the Name of Jesus’), no. 392 from Songs of Praise: Enlarged Edition (1931) [Layout C].

Example 2b. KINGS WESTON (‘At the Name of Jesus’), no. 443 from Songs of Praise (1925) [Layout D]. The text closely matches that of Example 2a and has been omitted except for the first verse, which appears in the original underlying the melody, as here.

But what of non-hymn tunes? The works cited so far meet the criteria in every particular — all are stand-alone strophic settings of metrical religious poems intended for congregational performance as part of a Christian worship service — but what about those in Table 1 that do not? famous men and guildford (nos. 7 and 9 in the Table) provide a point of entry. At first glance, these appear to be unison hymn tunes of the sort just discussed (here using Layout D), but closer investigation shows that famous men lacks a metrical text and is elaborately through-composed (not strophic) in form, while guildford’s text, though metrical and strophically set, is entirely devoid of religious content.Footnote 17 (The patriotic poem ‘England, arise!’ speaks in strictly secular tones of a national awakening, and was written by the atheist and iconoclastic advocate of gay liberation Edward Carpenter.) Both, accordingly, have been struck from my list. But it’s not enough merely to dismiss these tunes: commentary is needed, not least because their appearance in SoP and its later offshoot SoPE begs many questions. Vaughan Williams was enormously proud of SoP, viewing it as an improvement even on the 1906 EH because (as he told his friend Frances Cornford) ‘there’s not a single tune in it that I’m ashamed of’.Footnote 18 Emphatically, SoP is also a congregational hymn book, a ‘national collection of hymns for public worship’, as Percy Dearmer explained in his preface.Footnote 19 Given such statements, how could Vaughan Williams in good conscience admit into the book such obviously non-hymn tunes, including one (famous men) that leaves the musical abilities of the average church-goer far behind? (The tune has many changes of metre, some far-distant modulations, and irregular phrase lengths throughout — and all without a single strophic repetition, as noted.) Indeed, taken together, SoP and SoPE print nearly all the original hymn tunes Vaughan Williams had composed to date — thirteen in number — and all meet the criteria. Why, then, include two that do not?

The explanation speaks both to the unusual history of the unison hymn tune and to the special character of SoP. To take the former point first, the unison hymn tune has its roots (somewhat surprisingly) not in church music but rather in the ‘unison song’ of nineteenth-century school and community music.Footnote 20 This subgenre of the choral song originated in the sight-singing movements of the 1840s and 50s as founded by the solfège innovators John Hullah and especially John Curwen, whose tonic sol-fa notational system became the best known.Footnote 21 But while the movement generally focused on teaching part-singing and thus on the promotion of oratorios, anthems, and part-songs, it most definitely encouraged unison singing as well. Indeed, in an age of growing literacy and self-improvement, the unison song filled a niche by providing simple music to be sung in schools (including Mechanics’ Institutes) and on public occasions. The 1870 Education Act greatly improved funding for school music and gave the genre a boost. Serious composers like Stanford and Elgar tapped into this market, writing easy-to-sing strophic songs but also more challenging through-composed ones that could be worked out in rehearsal. Texts and subject matter resembled those of the solo song, though the unique moral atmosphere engendered by massed unison singing seems to have encouraged themes of the collective rather than the individual. Often these were patriotic and folk songs, but more generalized topics of self-sacrifice and service to the community were also typical, gaining currency not only in the great public schools like Sherborne, Rugby, and Harrow — training grounds for the civil and colonial administration — but also within mass social and political movements fighting for a cause. Ethel Smyth famously composed the unison song ‘The March of the Women’ for the suffragist Women’s Social and Political Union, while Hubert Parry set William Blake’s ‘Jerusalem’ as a unison song for a 1916 ‘Fight for Right’ rally asserting the justice of the Allied effort in World War I. (A little uneasy about this wartime association, Parry was glad when ‘Jerusalem’ was likewise co-opted by the suffragist movement.)Footnote 22

Gradually, unison songs became hymns. Chiefly this happened in the public schools, where the unison song became the standard music of the school assembly, and since such assemblies typically took place in chapel, and were effectively folded into chapel services, some unison songs acquired sacred or quasi-sacred words and thereby became hymns. ‘Public school hymnody’, in fact, came to specialize in the unison hymn tune, as the second (1919) edition of The Public School Hymn Book demonstrates. Here, specially written unison tunes (mostly in Layout D) by Geoffrey and Martin Shaw, Percy Buck (music master at Harrow), and others employ vigorous tempi and spacious melodies in setting ‘muscular’ texts celebrating Christ as embattled victor and liberator. Many employ a march-like bass and instrumental interludes that invoke ceremony and seriousness of purpose. This is exactly the model that Vaughan Williams follows in abinger, king’s weston, and marathon (the latter written, significantly, for Songs of Praise for Boys and Girls). All are strophic, metrical, and broadly congregational, with a unison melody and a ceremonial tread. The poems they set strongly emphasize self-realization through social and national service. One, ‘I Vow to Thee, My Country’ by Cecil Spring-Rice and set to abinger, is only obliquely religious, managing through a few subtle images to link suffering for the nation with entrance into heaven. By 1931, when Vaughan Williams set it, the poem was already associated with Armistice Day.

famous men and guildford, to return to the two tunes under discussion, share many of these features: broadly unison melodies, marching treads, and masculine, community-minded texts. As such, it seems reasonable to consider them ‘one-off’ specimens of public-school hymnody. But differences matter. These are not proper hymn tunes, as defined above, but rather unison songs that have not fully made the transition to unison hymn tunes. This is self-evident with respect to famous men for the simple reason that it began life as a unison song and was never altered. Vaughan Williams initially published it in Curwen’s tonic sol-fa ‘Unison Song’ series in 1923, and then simply reprinted it in SoPE (though with the tonic sol-fa notation removed). Its elaborate through-composed form was thus never revised and brought into line with the strophic requirements of a hymn. Claiming the same for guildford is obviously more difficult since it originated in the pages of SoP and was given a hymn-like strophic setting from the first. That it also resembles abinger — counted as a hymn tune on my list — in every particular except for its non-religious text is another reason to question the designation (especially since the religious imagery in abinger is minimal, as noted). Significantly, the omission hasn’t bothered other Table 1 commentators, who unanimously designate guildford a hymn tune.

And yet we would do well to remember that school music in this period was a mixed repertory. There were hymns for chapel services and popular, folk, and patriotic songs for singing classes. Just about all of them were strophic and sung in unison, not just the hymns. Further, items from the second group were sometimes sung during assembly in the school chapel: it’s this practice that helped give rise to the unison hymn tune in the first place, as we have observed. guildford, in this performance tradition, would have adorned Empire Day or St George’s Day celebrations no less ably than ‘Land of Hope and Glory’ or other similarly rousing unison patriotic songs. famous men, whose quasi-religious text amounts to an ode to leadership, would have fitted the occasion too — and probably did so sometimes. A. H. Peppin, music master at Clifton and then Rugby between 1896 and 1925, held regular ‘congregational practices’ during which he introduced new hymn tunes. One can imagine him teaching famous men, or something like it, to the choir — possibly in his singing classes as well — thus forming a solid cadre of students who might then convey it, by rote and in stages, to the school population as a whole. Not that assembled boys singing famous men in chapel would suddenly turn it into a hymn tune, of course. But the effort required to sing this music, familiar in idiom yet subtly challenging, would have brought the students together in a memorable shared experience.Footnote 23

For in the end, it was community that Vaughan Williams and Dearmer were after. This brings us to the ‘special character’ of SoP and the second reason why it includes such anomalies as guildford and famous men. For while SoP was indeed a hymn book, it was also something more. Dearmer called it a ‘national collection of hymns for public worship’, as noted, but significantly, went on to add that it was ‘also [a repository] of such “spiritual songs” as are akin to hymns and suitable for certain kinds of services in church as well as for schools, lecture meetings, and other public gatherings’.Footnote 24 In short, the book was aimed not just at church congregations but also at schools and indeed all manner of institutions and situations where music was needed. (And quite successful it was for this very reason, too, going to a second, much enlarged, edition, six years later.)Footnote 25 Nor, on the educational front, was it popular only with the great public schools: state-run primary and secondary schools likewise used SoP, whose wide selection of sacred hymns and communal unison songs was equally suitable to their singing classes and morning assemblies.Footnote 26 Its mixed repertory included patriotic songs like sussex (‘Men of England!’) and freedom (‘O Beautiful, my Country!’), odes to ethical idealism by Whitman and O’Shaughnessy (pioneers and marylebone), and even extracts from the great poets — Herrick, Shelley, and others — in which reference to Christianity is tenuous at best (brookend and pembroke). There are even six specially designated ‘Choir Songs’, each in unison but of a formal and rhythmic complexity that would take a well-trained choir to master (oxonia and tenbury are representative). Significantly, these songs, all of which were specially commissioned from contemporary English musicians for the book, seem from the outset to have been intended solely for the choir, with the congregation receiving little to no consideration.Footnote 27

By this measure, as often as not, spiritual songs ‘akin to hymns’ meant material lying outside the genre. The editors’ effort to meet as many different occasions and constituencies as possible necessitated this, as did the special circumstances and conventions of school music performance. This is why even a tune like guildford, which so closely resembles a hymn tune, must ultimately be considered a unison song: lacking a properly religious text, it is indistinguishable from many patriotic songs that originated in the singing class or school assembly and that never quite made the transition to a hymn tune. It’s worth noting in this connection that guildford has never been reprinted in any other hymnal.Footnote 28 Apparently, that one small departure from the norm is not so small as it seems, and the tune has, for the reasons suggested here, been viewed as fundamentally lying outside Christian hymnodic tradition. The wisdom of undertaking a strict survey, and allowing only those items meeting all six criteria, here seems confirmed.

Whether SoP was also used in ‘lecture meetings, and other public gatherings’ is harder to gauge. Certainly, its use of abolitionist, temperance, and pacifist texts suggests a reaching out to broader political and social constituencies.Footnote 29 The inclusion of Parry’s ‘Jerusalem’ provides further evidence for this, even if by 1925 its wartime and suffragist associations were giving way to popular perceptions of it as a second national anthem. ‘Jerusalem’ is interesting in providing an example of a unison song that did make the transition to a hymn tune when transferred to a hymn book intended for use in public worship: thus far it has appeared in twenty-eight hymnals, many of them far more conventional than SoP. Footnote 30 It could do so because in all other areas — Blake’s religion-tinged metrical poem, Parry’s strophic setting — the original work conforms to the necessary criteria. The contrast with guildford and famous men is instructive.

The situation also sheds light on two Vaughan Williams works (nos. 24 and 25 in Table 1) not generally assumed to be hymn tunes. These are ‘A Hymn to Freedom’ and ‘A Call to the Free Nations’, unison songs with blatantly propagandistic but nonetheless quasi-religious texts that the composer wrote for the war effort (in this case World War II) and intended for large public gatherings. (The first is in Layout D, the second in Layout B, though a performance note in the latter also invites SATB choral singing.) The parallel with ‘Jerusalem’ is exact, except in this case the composer and G. W. Briggs, who wrote the words, seem to have actually envisioned them as hymn tunes from the first: both works meet all criteria and prominently employ the word ‘hymn’ in their title or subtitle (‘A Call’ is subtitled ‘Hymn for choral or unison singing’). Admittedly, neither made the leap to an actual hymn book like ‘Jerusalem’ did, though one can easily imagine them surfacing in a third edition of SoP, had that ever happened. Indeed, ‘A Hymn to Freedom’ is in the best style of public-school hymnody, with a broadly unison melody, a ceremonial organ tread, instrumental interludes, and talk of public duty and spiritual righteousness. (‘A Call’ is more austere and less expansive, though equally moralistic.) Further, the two were grouped together with similar works by other composers in Briggs’s Five Wartime Hymns (1942), and then were later reprinted (texts only) in his Songs of Faith (1945). This last publication contains some fifty poems, a ‘good many’ of which, Briggs writes in his preface, ‘have found their way into various hymn books’.Footnote 31

A near-miss is ‘The Airmen’s Hymn’ (no. 26 in the Table), another war-themed work in Layout D for unison voices with religious overtones (also using the word ‘hymn’ in its title) on a metrical poem by the Earl of Lytton. Conceived for a Westminster Abbey service honouring the Royal Air Force, the tune in the third verse moves into brand new melodic territory, making for a through-composed, not a strophic, form.Footnote 32 Like famous men, in other words, the work remains a unison song despite some resemblances to the hymn tune (though given the intended sacred venue, ‘anthem’ might perhaps be the most apt designation). Not cited in Table 1 but perhaps worth mentioning in this connection is ‘The New Commonwealth’ (1943), a unison song fashioned by Vaughan Williams from his music for the World War II propaganda film The 49th Parallel. It too closely resembles a hymn tune — religious/moralistic text, broad singability, even a strictly strophic form — but does not appear to have been intended for church services at any point.Footnote 33

*

So far we have focused on the radically new unison hymn tune and the composer’s reliance on Layouts B, C, and D, where the choir is in effect subordinated to the congregation. But in no way does this mean that Vaughan Williams was uninterested in more traditional approaches to hymnody, where the choir had a separate role to play. He may well have emphasized unison tunes in SoP and SoPE, where public-school hymnody had a strong presence, but it is important to remember that four new tunes written for those books — cobbold, magda, oakley, and white gates — invite choral participation. This is because they all use Layout A, where the expectation is that the choir, if present, will join with the organ in delivering the SATB harmony in support of the congregation. Indeed, the vast majority of tunes in SoP and SoPE use Layout A, just as they did in EH, and for this reason it’s hard not to come to the conclusion that, as an editor, Vaughan Williams actually preferred it. True, these tunes, in this layout, originated with other composers and earlier editors, but still it was Vaughan Williams’s decision to select them in such numbers. Copyright restrictions and the prospect of an awesome workload (imagine converting all of them to a unison layout!) doubtless also played a role in this. But there is also ‘positive’ evidence that he welcomed choral participation in his later work with hymn tunes, and quite warmly too. One is the somewhat surprising suggestion in SoP that its hymns, in some churches at least, might be sung ‘by the choir alone’.Footnote 34 Another is that the same book contains many fauxbourdon and descant settings, where countermelodies and elaborate choral textures envelop and enshroud the main tune sung by the people. These are among SoP’s most striking innovations, and demonstrate beyond doubt Vaughan Williams’s concern not only to include the choir in hymn-singing but to give it a chance to shine.

Do these choral provisions directly contradict Vaughan Williams’s ‘congregationalist’ emphasis or signal a secret endorsement of the Victorian preference for the ‘trained choir’ over ‘the people’? The answer is a ringing no, and for the same reason given earlier — that Vaughan Williams believed the choir and congregation working together helped elevate the latter artistically and that this, in turn, ultimately encouraged the people to take an active role in the music. What’s particularly interesting about this train of thought is that it fundamentally endorses a Victorian point of view which Vaughan Williams otherwise famously scorned. As touched on briefly near the beginning of this essay, it was a Victorian ambition to raise church music to the level of art music; they did so by adapting learned techniques in an effort to imbue the humble hymn with the ‘grand effects’ of art music. Vaughan Williams’s hymn tunes are no different. Their sophisticated part-writing and phrase elisions, their flexible methods of text-setting and orchestrally conceived organ parts, their organically forward-driving melodies — all are Victorian innovations that he extended and refined.Footnote 35 The same goes for his handling of the choir. Vaughan Williams may have demonstrated an antipathy to Victorian aesthetics by trimming repertory and curbing chromaticism, but when it came to the choir he directly expanded and built on those aesthetics. And he did so, in effect, by blending Victorian choral traditions with his own congregationalist concerns.

The trick was to ensure that the choir did not swamp the people. Hence, once again, the preference for Layout A, which allowed for choral SATB harmony and its ‘artistic’ textural and timbral contrasts, even as the editorial directive that the people sing the melody only ensured that the congregation kept on track. Still, he took no chances, urging that the first verse be sung in unison (that is, before the choir broke into any harmony) and marking the occasional verse to be similarly sung. He even authorized what in the EH he called the ‘experiment’, then obtaining in some churches, of having ‘choir and people sing some hymns antiphonally’.Footnote 36 His suggestions invite a range of unison, harmonized, and even a cappella verses, one following another. (The possibilities, which in effect involved mixing the various layouts we are already familiar with, are listed under Layout E in the Appendix.) Vaughan Williams evidently believed that antiphonal singing would encourage rather than discourage congregations; certainly, he believed it would improve their artistic sensibilities. ‘By this means,’ he wrote, ‘the people are given a distinct status in the services, and are encouraged to take an intelligent interest in the music they sing.’Footnote 37

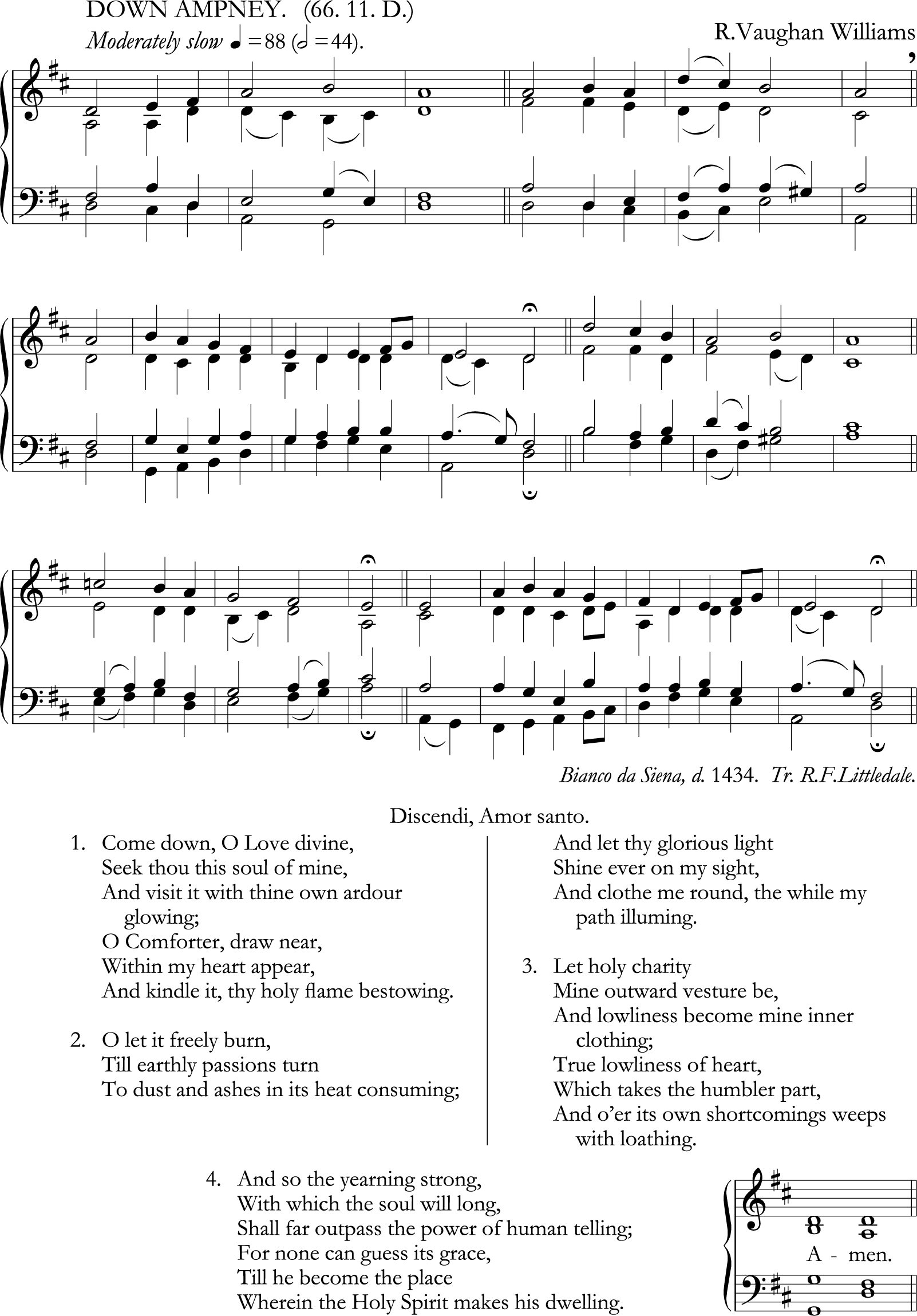

And yet. An antiphonal approach presupposes that the congregation is not to sing the tune all the way through and, indeed, will be silent for portions of a performance. Does such a practice compromise these works as proper hymn tunes, according to our definition? The answer is obviously no, if only because these are performance suggestions only. A cathedral or major parish church might well undertake an antiphonal rendering, but this would not be likely or even possible in a small rural parish, especially one using a ‘words only’ edition. There, the strophic repetition of the tune, and the constant presence of a powerful organ part with the melody always in the top voice, would provide sufficient guidance and support for a congregation ‘going it alone’. Still, it is significant that Vaughan Williams’s notation for these Layout E tunes actively encouraged a varied vocal approach. The words ‘Unison’ and ‘Harmony’ appear above the different verses of sine nomine — above specific bars in the case of randolph — while in salve feste dies, a tune sung in unison throughout, the more difficult verses are specifically assigned to ‘Clerks only’, an unambiguous reference to the choir singing alone, without the people (who are to be silent at these points). (See Figure 1.) Even this seems to be only a suggestion, though, given that Vaughan Williams later reprinted salve feste dies in Layout C in SoPE, where it is to be sung in unison (choir and people) throughout. Clearly, he believed that with sufficient organ and (when present) choral support, the people could indeed sing the tricky triplets and chromaticism of the verse sections. Probably the ‘Clerks only’ direction was intended for festive occasions, where this unusually intricate hymn tune, whose different strains for odd and even verses provide extreme contrast to the simpler, straightforward refrain, could be heard to splendid antiphonal effect.

Figure 1. SALVE FESTA DIES (‘Hail Thee, Festival Day!’), no. 624 from The English Hymnal (1906) [Layout E(d)]. This antiphonal hymn tune is sung in unison throughout, with congregation and choir in the refrain (‘Clerks’), and choir alone in the verses (‘Clerks only’).

Victorian notions of the hymn tune as art music are inescapable here, and indeed, it seems fitting that these Layout E hymn tunes, the most elaborate Vaughan Williams ever wrote, appeared near the start of his career, in the 1906 EH. Footnote 38 Not that he abandoned choral elaboration thereafter, of course. We saw that he wrote some new Layout A tunes for SoP and SoPE, and how as music editor of those books he continued to encourage vigorous choral participation. But the point is worth emphasizing, if only because the principle of choral elaboration, and choral antiphony generally, in hymn-singing was beginning to take on a life of its own in Anglican music around this time, prompting the emergence of a new, if closely related, genre that also has a bearing on our story. This was the so-called ‘hymn-anthem’, defined by Routley as ‘essentially hymn tunes set with varied organ part, varied choral treatment, descant, fa-burden, and any other composer’s device that will turn three or four verses of the same tune into an attractive anthem’.Footnote 39 Interestingly, the genre appears to have emerged as a consequence of diminishing choral membership during and after World War I: anthems based on hymn tunes were easier to work up for church performance, and might well involve the congregation to bolster vocal forces. This was possible because the hymn-anthem pointedly drew on well-known hymn tunes and presented the melody strophically, verse by verse. Still, the level of musical elaboration — the addition of descants, instrumental interludes, significant rhythmic variation in different verses of the tune, and extensive SATB counterpoint, especially near the end — meant that this was a choral work with congregational involvement, not the other way around. Its occupation of the anthem ‘slot’ in the service confirms this.Footnote 40

Vaughan Williams produced a number of hymn-anthems of this sort — At the Name of Jesus (1927), All Hail the Power (1938), and most famously The Old Hundredth Psalm Tune (1953, for the coronation of Elizabeth II) — and it’s noteworthy that none of them mistakenly appear in Table 1. Yet we should note that it is theoretically possible to produce a bona fide hymn tune, performed as a hymn tune, under these guidelines, provided the choral elaboration is not excessive and the strophic presentation of the tune (the people’s part) is never altered or interrupted. Routley’s reference to ‘descant’ and ‘fa-burden’ treatment seems, in fact, exactly to describe those hymn tunes from SoP, mentioned earlier, that are outfitted in just this way — tunes where the congregation sings the melody and the choir’s fauxbourdon and descant introduce countermelodies and textural elaboration that develop and enshroud it. ‘In these cases,’ Vaughan Williams explained in an editorial note, ‘both choir and people have their definite part to perform.’Footnote 41 Here, at least, the hymn-anthem is more hymn than anthem.Footnote 42

Whether this is also true of My Soul Praise the Lord (no. 23 in Table 1) is more difficult to say, judging from the split opinions of commentators.Footnote 43 Not that anyone seems to have recognized its obvious connections to the hymn-anthem. The work sets four verses from William Kethe’s celebrated metrical version of Psalm 104, the first two in vocal unison, the third in unison with a descant, and the fourth employing complex vocal SATB counterpoint. All are separated by an instrumental interlude. Where the work differs from the standard hymn-anthem, including Vaughan Williams’s three listed above, is that it is based on a brand new tune by the composer, not an already established one. Routley would no doubt place it among what he calls ‘anthems in hymn-anthem form but using a tune by their own composer’, and I tentatively do the same.Footnote 44 Yet one also notes a clear strophic repetition of the tune throughout, even in the last verse, where the melody is presented intact in the alto voice amid the vocal counterpoint. And when we consider the score direction indicating that this last verse ‘may be sung in unison if preferred’, it’s very tempting to join with some Table 1 commentators and consider this a unison hymn tune with a descant in the third verse. Still, the fact that the unison is optional points to a fundamentally choral conception for the work. Nor does the intact presentation of the tune amid the SATB fourth-verse elaboration quite fit the model of the SoP ‘fauxbourdon’ hymn tune examples, for the simple reason that there is no indication that the congregation is to sing the alto line at all. Presumably, if the melody had come from a well-known hymn tune, the words ‘people’ or ‘people’s part’ would have been placed there (as in Vaughan Williams’s recognized hymn-anthems). Lacking this direction, it’s anyone’s guess whether the composition is a choral anthem ‘in hymn-anthem form’ (in Routley’s formulation) or an unorthodox hymn-anthem based on a newly introduced tune with optional congregational part. What it is not is a hymn tune.

Also not hymn tunes are the four carols that Vaughan Williams wrote for The Oxford Book of Carols (TOBC; these appear as nos. 13–16 in the Table.) The fact that few commentators include them on their list does not mean that ruling them out is easy, however. The argument against them is that carols are generally viewed as the extraliturgical songs of everyday people, and also that they circulated in oral tradition as part of a largely secular folk process.Footnote 45 The argument for them is that carols generally, if not universally, employ a religious metrical text and use the same strophic (usually strophic-plus-refrain) musical structure that hymn tunes do. (The four Vaughan Williams carols conform on all counts.) Also in their favour is that, during the nineteenth century, the ‘Christmas carol’ became a fixture of Victorian hymnody — part of the genre’s absorption of art and folk material during that period that we have remarked earlier — and, further, that Vaughan Williams himself included examples in his own hymn books. EH, SoP, and SoPE reprint many European carols that Victorian editors had already adapted as hymn tunes and set to new words; the books also include a fair number of folk carol melodies collected ‘in the field’ by the composer himself and by others, similarly adapted as hymn tunes with new texts.Footnote 46

From this, it might seem that Vaughan Williams regarded carols and hymns as highly compatible, but this would be wrong. The Preface to TOBC makes it clear that the editors viewed the Victorian enthusiasm for ‘old carols’ as pure sanctimony, an antiquarian fetish analogous to the ‘sham Gothic’ of so many nineteenth-century churches with their ‘renovated interiors’.Footnote 47 In this reading, the adaptation of carols into hymns only distorted and corrupted them. Not only were carols not exclusive to Christmas (as the Victorians wrongly supposed) but their being so relegated was itself part of a centuries-long campaign by the Church to curb the spontaneous ‘hilarity’ (unruly joyfulness) of ordinary people by limiting them to a single period of the year.Footnote 48 Here was another cause that the composer’s anti-Victorianism, not to mention his radical politics, could get behind. If he reprinted the ‘carols’ of Victorian editors in his hymn books, then, it was merely as a reluctant nod to popular taste. This low opinion of the practice explains why he avoided pairing the carol melodies from his own collection with Christmas texts (they were generally placed in the children’s section instead) — indeed why he avoided pairing them even with their original traditional texts (texts, after all, that were no less pious and devotional than the ones selected to replace them). Clearly, ‘genuine carols’ had no place in a hymn book, even when they were newly written, as here. Hence Vaughan Williams’s decision not to reprint any of his four original carols in SoPE, the 1933 EH, or any other later hymn book. Far better, in fact, to keep them pure and undiluted in a separate carol book that could be used to supplement worship services — something that Dearmer rather boldly suggests on the last page of his preface: ‘We think that carols might be continuously sung in ordinary parish churches’, he writes, adding significantly that ‘carol-books […] in continual use’ would help ‘increase the element of joy in religion’.Footnote 49 TOBC’s suitability for this purpose is broadly implied.

*

The remaining five items in the Table are quickly dispatched, as they unambiguously conform to the necessary criteria. All have metrical religious texts, a strophic musical structure, and were intended for Christian congregational worship services. Four of them call for unison singing, though the layouts vary slightly (see Appendix). st margaret (no. 27), with words by Ursula Wood (who later married Vaughan Williams), was written for The Hymnal for Scotland, Incorporating the English Hymnal, while little cloister (no. 22) was intended for an already-published hymn by Percy Dearmer from SoPE that apparently never made it into subsequent printings (it was issued separately by Oxford University Press).Footnote 50 alma chorus and triumphe! plaudant maria appeared in The New Office Hymn Book (1907), a ‘niche’ Anglo-Catholic publication giving modern translations of old service books — introits, graduals, sequences, office hymns, etc. — along with their original chant melodies, as well as modern metrical substitutes (as in the case of Vaughan Williams’s two tunes). The book appears not to have had a wide circulation, which may explain why it has eluded Vaughan Williams scholars until now. Indeed, I was alerted to the two tunes only through a passing reference by the indefatigable Erik Routley.Footnote 51

The fifth and last hymn tune, cobbold (no. 19 in the Table), was composed jointly with Martin Shaw and appeared in SoPE. When not overlooked altogether, this tune has been mistaken as a Vaughan Williams arrangement, most likely because commentators have missed the joke and taken the note on the score — ‘Based on a melody by S. M. W. V. R’ — to be an uncrackable enigma. But, of course, this is ‘R[alph] V[aughan] W[illiams] M[artin] S[haw]’ backwards, making them the joint composers of the tune, melody and harmony both. It’s true that ‘Cobbold’ was the maiden name of Shaw’s wife, and it’s just possible that some commentators have assumed from this that Shaw wrote the melody and Vaughan Williams arranged it. But writing tunes without reference to harmony is generally not how composers go about their business, and it’s to be doubted that many commentators knew about the Cobbold connection, besides. The SoPE acknowledgements page grants copyright for the tune to both musicians, and from this we can safely assume it was jointly composed by them.

*

Thus does this revised works list yield a grand total of nineteen original hymn tunes written fully or in part by Vaughan Williams. Hopefully, the consistent application of my six-point definition inspires confidence in those who would finally ‘nail down’ the number of works in the genre by one of the great hymn-tune composers of the age. Just as important, though, is that the method has opened a window on the many contingencies impacting the humble hymn tune. Hymn tunes may appear to be a simple matter of setting a religious strophic text to be sung by Christian congregations, but in fact they involve a whole host of musical and cultural negotiations — with traditions of school and community music, for example, and interactions with ‘hymn-adjacent’ genres like the unison song, the carol, and the hymn-anthem. These contingencies have been little discussed in the literature: recognizing them helps us understand the complexities of early twentieth-century Anglican musical culture and, ultimately, quickens our appreciation of Vaughan Williams’s achievement. In retrospect, it seems almost amazing that the man who took the opulent choral aesthetic of the Victorians to its logical culmination in the splendidly antiphonal tunes of EH also produced the austerely unison ‘experiments’ (as Routley calls them) of SoP and SoPE.

Uniting both approaches, of course, was an unswerving dedication to ordinary people. The support Vaughan Williams gave amateur musicians throughout his career is closely echoed by his tireless efforts to encourage musically inexperienced congregations to sing with confidence. It might be argued that Vaughan Williams’s support of the average church-goer actually intensified over time: that the giving way of the antiphonal and varied textures of the 1906 EH (where congregation and choir only sometimes sang in unison) to the unison hymn-tune layouts of SoP and SoPE (where they always did so) represented a shift in his priorities. But this is to forget the continued choral provision in these later hymn books, including their use of descant and fauxbourdon, not to mention the importance of the unison layout to the books’ educational focus. And when we consider the careful thought that went into how Vaughan Williams used the choir to encourage the people in those early hymn tunes — thought that demonstrably includes a psychological component — it’s impossible not to conclude that all of his tunes, from every period of his career, conform to the aesthetic principles he forthrightly announced in his EH preface:

In the hymn [the choir] must give way to the congregation, and it is a great mistake to suppose that the result will be inartistic. A large body of voices singing together makes a distinctly artistic effect.Footnote 52

Appendix: Vaughan Williams’s Original Hymn Tunes Classified by Type and Notational Layout

Vaughan Williams’s main aesthetic goal as a hymn-tune composer was always to encourage unskilled congregations to participate vocally in Christian worship. But there were different ways to do this, and these are reflected in his methods of notation. Layouts A, B, C, D, and E describe the different ways his tunes could appear on the page, as discussed in this essay. In all cases, some variability is possible. An organ was always to be present, and very often the choir, though the presence of the latter was optional and dependent on local conditions.

Layouts B, C, and D require some explanation, as they represent three different ways to notate a single phenomenon, the unison hymn tune. The three are all very similar in terms of sonic result and are differentiated in this essay in order to be precise vis-à-vis the sources, and also because Vaughan Williams sometimes switches from one layout to another when reprinting a tune in a later hymn book (it’s unclear just why this is). I have indicated any tune receiving such varied treatment by listing it simultaneously under the different layouts, with dates that correspond to the four major hymn books, as follows: 1906 (EH, 1st edn), 1925 (SoP, 1st edn), 1931 (SoPE), 1933 (EH, rev. edn). Thus king’s weston first appeared in Layout D in SoP and later in Layout C in SoPE and EH (rev. edn). Note that the layout changes sometimes also involve Layout E, since those tunes usually include portions sung in unison. Finally, in the list below, any tune name without a date means it appeared in only the one layout.

Examples 1 and 2(a and b), in the body of the text above, offer examples of Layouts A, C, and D, respectively, while Figure 1, also in the text, exemplifies Layout E(d).

Layout A: Hymn tunes in ‘Victorian’ SATB layout: four-part harmony on two staves. No performance direction is given on the page, though an editorial note in the prefatory material directs the congregation to sing the melody only. The SATB harmony can be either played by the organ alone, sung by the choir alone, or performed by choir and organ together.

Examples: ‘A Call to the Free Nations’, cobbold, down ampney, magda, oakley, white gates.

Layout B: Unison hymn tunes formatted exactly as in Layout A but with a performance injunction published at the head of the score calling for ‘unison singing’ or ‘unison voices’. No vocal harmony is allowed; the choir, if present, must sing the melody with the congregation; the organ alone plays the harmony.

Examples: cumnor, little cloister.

Layout C: Unison hymn tunes formatted on two staves as in Layout B and with the exact same performance directions, except that the organ part has ‘looser’ counterpoint (alternating between three and six parts).

Examples: king’s weston (1931, 1933), mantegna, marathon (1931), salve feste dies (1931), st margaret.

Layout D: Unison hymn tunes formatted on three staves, with the melody on the top stave above and a designated organ part appearing on the two lower staves (bracketed), but otherwise with the exact same counterpoint and performance directions as in Layout C.

Examples: ‘A Hymn of Freedom’, abinger, alma chorus, king’s weston (1925), marathon (in Songs of Praise for Boys and Girls, 1929), triumphe! plaudant maria.

Layout E: Antiphonal hymn tunes utilizing a variety of means to alternate unison and choral singing (though the latter is a suggestion only and might also be sung in unison); these ‘mix and match’ the layouts listed above as follows:

-

a. Layout B for sections with all voices in unison; Layout A for sections with SATB vocal harmony. Example: randolph.

-

b. Layout C for sections with all voices in unison; Layout A for sections with SATB vocal harmony. Examples: sine nomine (1931, 1933).

-

c. Layout D for sections with all voices in unison; Layout A for sections with SATB vocal harmony. Example: sine nomine (1906, 1925).

-

d. Sung in unison throughout (using Layout C) but with two contrasting sections: one for choir and congregation, the other for choir only. Example: salve feste dies (1906, 1925, 1933).