Introduction

Crowding in emergency departments (ED) is a long-standing international issue (Di Somma et al., Reference Di Somma, Paladino, Vaughan, Lalle, Magrini and Magnanti2015) and demand continues to rise (Coster et al., Reference Coster, Turner, Bradbury and Cantrell2017). While most research conducted in this field derives from the UK and US, the problem is global in scale (Savioli et al., Reference Savioli, Ceresa, Gri, Bavestrello, Longhitano, Zanza, Piccioni, Esposito, Ricevuti and Bressan2022). A key factor in the overburden of EDs is the resource implications associated with repeat attenders with common clinical presentations such as chronic physical health problems (Pines et al., Reference Pines, Asplin, Kaji, Lowe, Magid, Raven, Weber and Yealy2011), poor mental health (Hunt et al., Reference Hunt, Weber, Showstack, Colby and Callaham2006), and alcohol and substance misuse problems (Lynch and Greaves, 2000). Best practice guidance on supporting repeat attenders in the ED states that psychological therapies should be provided (Royal College of Emergency Medicine, 2017). Existing research demonstrates that these aforementioned repeat presentations are amenable to commonly utilized and efficacious psychological interventions such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), signalling that early intervention in the ED may offer opportunity to prevent repeat attendance for the same problem. However, despite extensive evidence supporting the utility of CBT in the most common ED presentations such as non-cardiac chest pain, panic and medically unexplained symptoms (MUS), and the proliferation of psychological therapists in the field of medical psychology (McAndrew et al., Reference McAndrew, Friedlander, Litke, Phillips, Kimber and Helmer2019), the efficacy of such interventions delivered in the ED has not been established.

Clinicians in the ED commonly refer patients to psychological therapy on discharge, but engagement with therapy post-discharge is often low. This is particularly the case in complex groups such as those with MUS (Balabanovic and Hayton, Reference Balabanovic and Hayton2020), trauma symptoms (Kantor et al., Reference Kantor, Knefel and Lueger-Schuster2017), and where attendance is precipitated by psychological distress associated with physical symptoms, rather than the physical symptoms per se (Daniels et al., Reference Daniels, Griffiths and Fisher2019). In these instances, early intervention is required, with a focus on targeting barriers to engagement (e.g. treatment-related doubts, perceived stigma, misperceptions) which can be addressed collaboratively between medical staff and psychological therapists (Kantor et al., Reference Kantor, Knefel and Lueger-Schuster2017). Previous research has established that engagement in psychological therapies in the ED has been directly associated with positive treatment outcomes and reduced attendance (Holdsworth et al., Reference Holdsworth, Bowen, Brown and Howat2014), with cost savings of £1 to every £7 spent, in medical psychology-led ED interventions (Dr Foster, Reference Foster2018) which supports the rationale for psychology in emergency care. Indeed, engaging patients within the ED may be more acceptable for those with pronounced physical symptoms and a psychological component (Carroll et al., Reference Carroll, Moss-Morris, Hulme and Hudson2021; Marks and Hunter, Reference Marks and Hunter2014).

Advances in our understanding of the utility of psychological interventions in the ED would inform future service planning and development which has the potential to improve patient outcomes and reduce strain on EDs. This is particularly relevant given the extensive evidence base for psychologically based interventions in medical conditions, primarily CBT, through the expansions of psychological therapy into long-term conditions (NHS England, 2018) via Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) services. Given the pressures on the ED, the amenability of many medical conditions to psychological therapy and the growth of the evidence-based psychological workforce, what works and for whom becomes an important question.

This review aims to address this knowledge gap by using a systematic approach to evaluate the literature to establish whether psychological interventions, particularly CBT, are feasible to deliver in the ED, acceptable and effective at improving pre-defined patient outcomes for adults who attend the ED with physical health complaints as their primary concern. We purposefully (a) retain a broad view of psychological therapies to ensure a comprehensive view of the theoretical underpinning and modalities and (b) include all study designs, in order to gain a fuller picture of the state of the evidence, appropriate to the parameters of the first systematic review of its kind.

Method

This systematic review protocol is registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; CRD42018087860). The review follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009).

Search strategy

Three electronic databases were used for this systematic literature review: Cochrane, PubMed and APA PsycNet. There were no restrictions on date, language, publication status or study design. Interrogation of the databases conducted 27 May 2020 used adapted terms following the PICO (Population, Intervention, Control, Outcome) elements of our research question.

Study selection

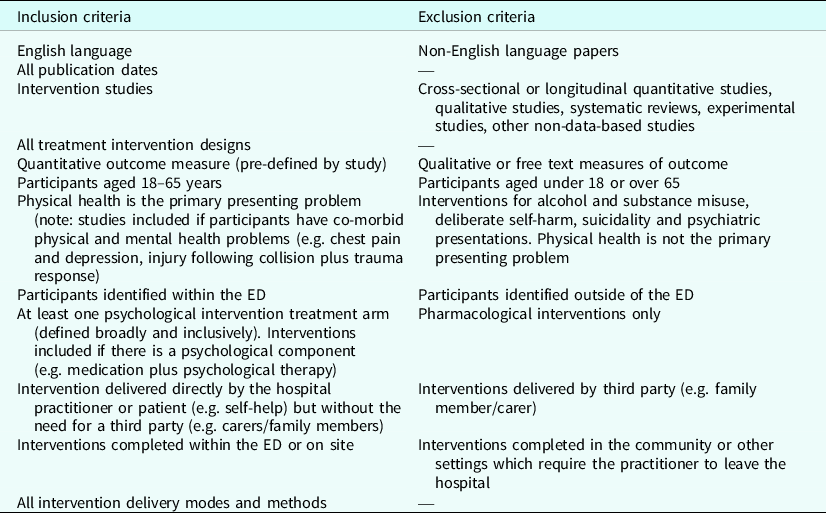

All intervention study designs meeting criteria were eligible for inclusion; as the first review to explore this area, all designs were deemed relevant to the research question. Evidence from non-randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were considered in context of the limitations in design and risk of bias; the broad and inclusive scope allows the optimal capture of the current state of knowledge in the field; see Table 1 for full inclusion and exclusion criteria. Data relating to the quality of psychotherapeutic interventions were also extracted, drawing from authoritative reviews of quality assessment criterias for psychotherapies (Chambless and Hollon, Reference Chambless and Hollon1998; Liebherz et al., Reference Liebherz, Schmidt and Rabung2016). Specific references were made to the following: a theoretical framework, level of therapist training, number of drop-outs reported, identification of inclusion and exclusion criteria, and whether the integrity of the intervention was checked.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

S.McG. conducted database searches and screened abstracts and full texts in order to determine if they met the inclusion criteria. Following removal of duplicates, 20% of abstracts and full papers were reviewed by an independent analyst (S.L.) for quality assurance purposes.

Quality assessment

The Cochrane Risk of Bias tool (Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Thomas, Chandler, Cumpston, Li, Page and Welch2019) was used to assess study level bias by two study authors independently (S.McG. and M.H.S.). Studies were rated high, low or unclear on the following domains: selection which includes sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding of participants and personnel; blinding of outcome; attrition; selective reporting; other bias and overall risk of bias. A Grading of Recommendations Assessment Development and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology and a GRADE summary of findings table was planned.

Results

Search results

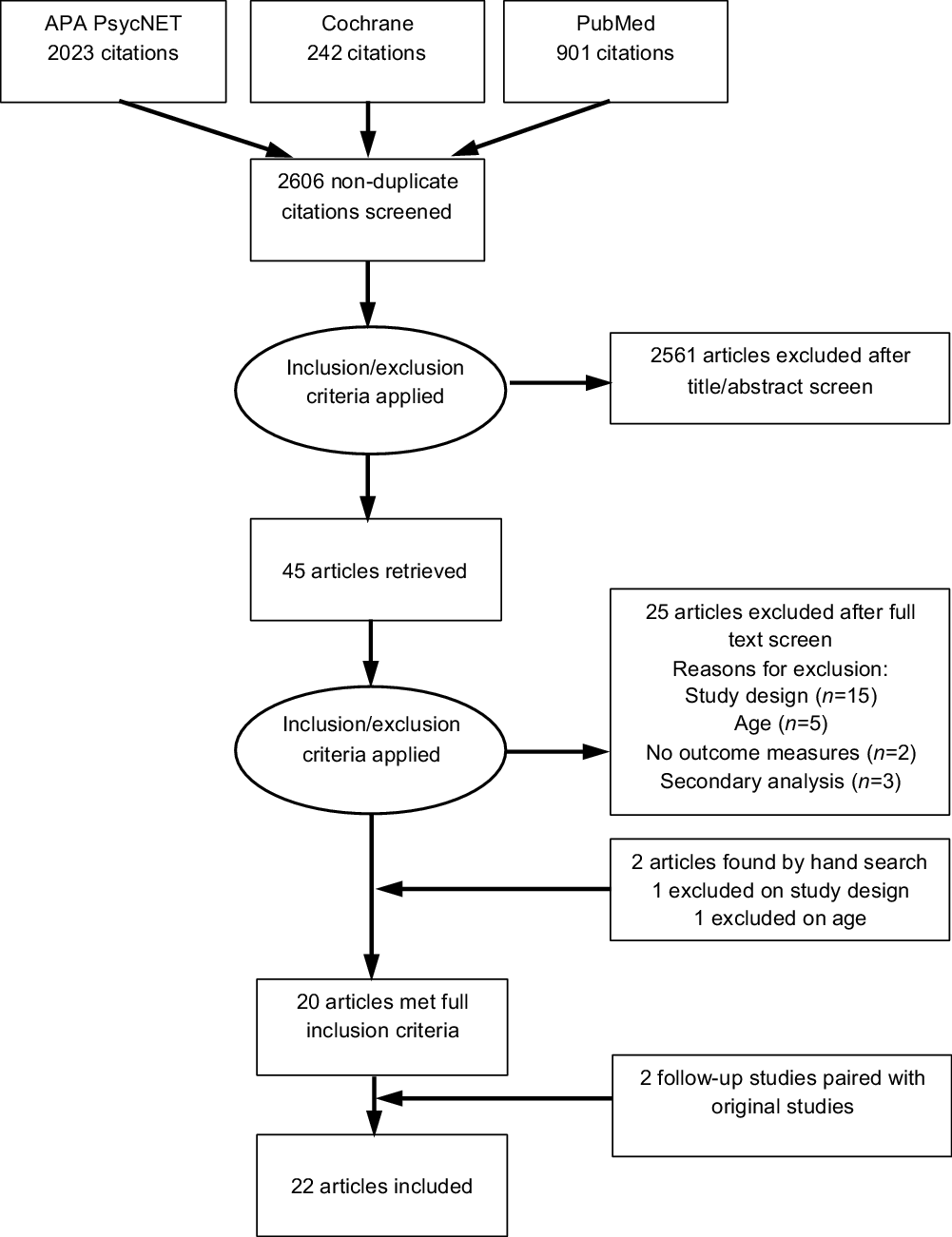

After duplicates were removed, 2606 records were screened (see Fig. 1) for inclusion. Of these, 45 were taken forward for full text review, with 20 studies eligible for inclusion. Authors of included papers were contacted to identify unpublished papers; however, no additional papers were included on this basis.

Figure 1. PRISMA diagram of systematic literature search conducted.

Of the papers reviewed by an independent analyst (S.L.), 20% of the abstracts (n = 289) and full texts (n = 8) attained ‘substantial’ co-rater agreement (abstracts: Cohen’s κ: 0.66, 98.6%; full texts: Cohen’s κ: 0.75, 87.5%) and one paper was subject to discrepancy but this was resolved by discussion.

Quality of evidence

The overall risk of bias across the studies was high, with only five studies (RCTs) gaining ‘low’ overall risk of bias status (25%). Categories consistently rated as ‘high’ or ‘unclear’ included blinding of participants and assessors and outcome reporting; however, ratings were mixed overall (see Table 2). A meta-analysis and GRADE table was planned but deemed non-viable nor clinically meaningful given the heterogeneity of study design and outcomes, particularly given the lack of homogeneity in the clinical groups and breadth of outcomes used.

Table 2. Risk of bias for all studies included in review

Study characteristics

Study designs included RCTs (n = 8), non-RCT studies (n = 10), case studies (n = 2), and two follow-up studies which were coupled with the original papers. Studies originated from seven countries: USA (n = 7), UK (n = 4), Canada (n = 5), China (n = 1), The Netherlands (n = 1), New Zealand (n = 1) and Australia (n = 1) (see Table 3 for study characteristics). Thirteen of 20 studies were both initiated and completed within the ED, and seven were initiated in the ED and completed on site (observation units, cardiac clinics or wards, surgical wards, clinical psychology clinic). Most studies (65%, n = 13) were delivered by a psychological therapist; other delivery personnel included social worker, nurse, researcher, clinician (not specified), psychiatric professional and health educator (n = 7).

Table 3. Study characteristics of studies included

+, positive significant outcome; <>, outcome could not be reliably interpreted; +*, positive but non-significant outcome.

Intervention characteristics

Of the included studies, 90% (n = 18) were underpinned by a cognitive and/or behavioural approach, 5% (n = 1) a behaviour-change counselling approach, and 5% (n = 1) psychodynamic in orientation. Studies were protocolized to either one (n = 4), two (n = 13), or three active treatment conditions (n = 3). The number of sessions per therapist delivered intervention varied, with some (35%, n = 7) studies delivering one session, and 65% (n = 13) delivering two or more sessions (see Table 3). Session duration ranged from 10 to 120 minutes, with a modal duration of 1 hour.

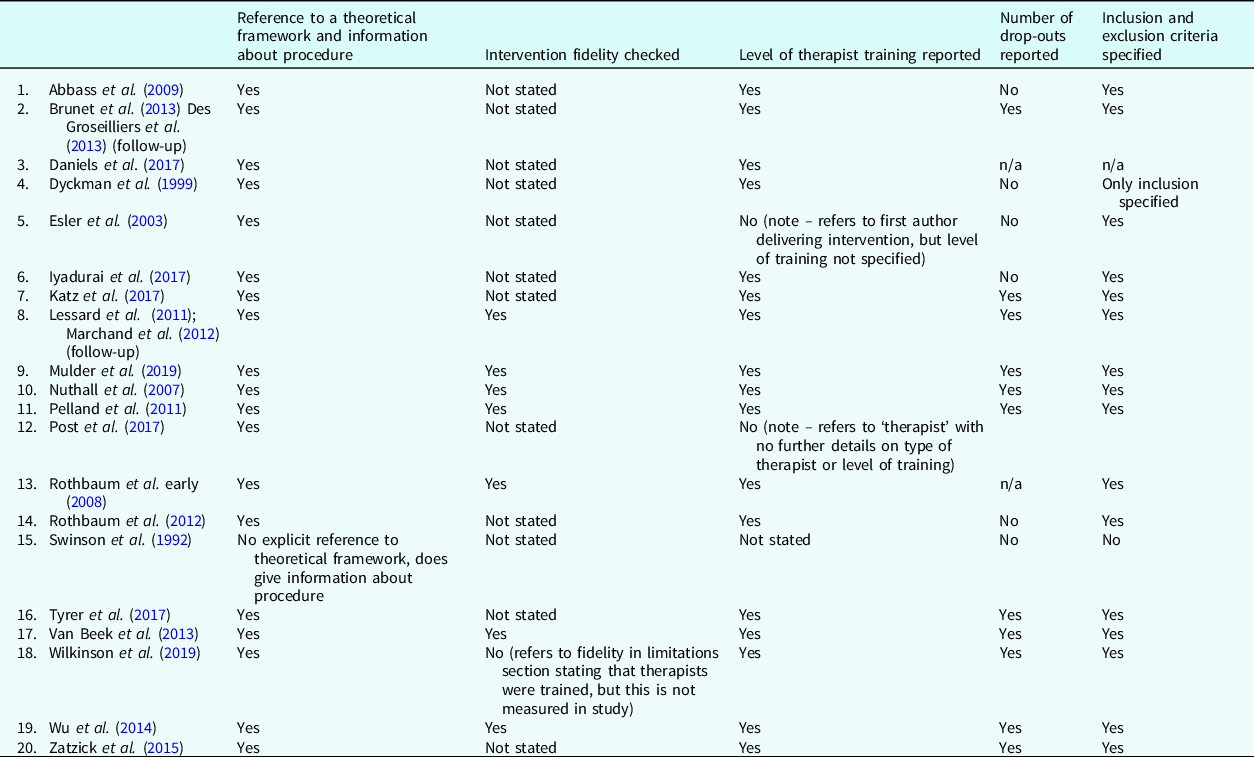

Quality of psychotherapeutic intervention

Eighteen of the 20 studies (90%) refer to an underpinning theoretical framework, 16 of which provide a rationale for the relevance of theoretical application to the intervention. The remaining two studies referred to brief psychiatric interventions focused on exposure treatment but in the absence of theoretical underpinning. All studies provided information about the procedure. Seven of the 20 studies (35%) reported checking for intervention integrity, using a structured therapeutic integrity instrument (n = 1), and audiotaping treatment sessions to check for adherence to the planned intervention and by comprehensively manualizing the sessions (n = 6).

Sixteen studies (80%) reported the level of therapist training including information pertaining to their qualifications. Of the remaining studies, two studies referred to therapists delivering the intervention, but the level of training or qualifications were not reported, one study did not state the level of training or qualifications, and one study referred to a technological intervention with no therapist required. The number of drop-outs were reported by 60% (n = 12) of the studies, six did not report drop-outs, and for two studies the number of drop-outs were not applicable given the studies’ single case study design. Finally, inclusion and exclusion criterion were reported by 17 studies (85%), one study only reported the inclusion criteria and two studies reported neither (see Table 4)

Table 4. Quality of psychotherapeutic intervention

Study outcomes

Outcomes varied according to presentation, which naturally emerged into four groups: trauma/PTSD-prevention (n = 7); panic attacks (n = 5) non-cardiac chest pain (NCCP; n = 5) and miscellaneous (n = 3).

For trauma related studies, the PTSD Symptom Scale Interview (PSS-I) was the most commonly used primary outcome measure (n = 3). Other measures included the Post-traumatic Diagnostic Scale (PDS; n = 2), the Impact of Events Scale-Revised (IES-r; n = 2), Post-trauma Checklist (PCL-5; n = 1) and idiosyncratic measures (n = 1).

In the panic-related studies, two used the Anxiety Disorder Interview schedule for DSM-IV (ADIS-IV) to assess severity of panic as the primary outcome measures, and one study used the self-rating version of the Panic Disorder Severity Scale (PDSS-SR). Other measures included ED attendances (n = 1), Fear Questionnaire (FQ; n = 1), the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; n = 1), the mobility inventory (MI; n = 1) and frequency of panic attacks (n = 1).

NCCP primary outcome measures included chest pain frequency and severity (n = 1), Anxiety Sensitivity Index (ASI; n = 1), Cardiac Anxiety Questionnaire (CAQ; n = 1), patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9; n = 1), Generalized Anxiety Disorder measure (GAD-7; n = 1), Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS; n = 1), ED usage data (n = 1) and the Short Health Anxiety Inventory (SHAI; n = 1).

Studies in the miscellaneous group reported a broad range of outcome measures (see Table 3) including the cardiovascular risks of the Health Motivation Assessment Inventory subscale (HMAI; n = 1), adapted health belief scale (OHBS; n = 1), SHAI (n = 1), PHQ-9 (n = 1), GAD-7 (n = 1) and the Cardiac Diet Self-Efficacy Index (CDSEI; n = 1). Four of the 20 studies (20%) reported the impact of intervention on ED attendance.

As reflected in Table 3, there was little consistency in relation to the choice of outcome measures or primary outcome measures in clinical groupings, with 11 of 20 studies (55%) reporting a clear primary outcome measure.

Descriptive (narrative) analysis of findings

Studies are discussed in relation to their clinical groupings in order to promote a coherent synthesis of findings.

Trauma/post-traumatic stress disorder prevention (n = 7)

Two RCTs used a CBT approach to prevent PTSD; both interventions reported effectiveness. One study (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Li and Cho2014) offered brief CBT (B-CBT) to patients showing a moderate level of distress (measured by IES-R) following a motoring accident, with a comparison group receiving self-help guidance. B-CBT consisted of four, 1.5-hour weekly sessions with participants encouraged to produce written and verbal accounts of their motoring accident, where cognitive distortions could be targeted (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Li and Cho2014). B-CBT reduced psychological distress at 3 months (p = .004) HADS-A and HADS-D at 6-month follow-up (HADS-A: p = .044; HADS-D: p = .013) but there was no statistically significant difference in IES-R effect score, the primary outcome variable. The study was under-powered and lacked a treatment control, undermining confidence in the findings. Brunet et al. (Reference Brunet, des Groseilliers, Cordova and Ruzek2013) described a two-session CBT intervention which found a modest effect on the primary outcome (d = 0.39) when improvement in the control participants was controlled for. The 2-year follow-up study (Des Groseilliers et al., Reference Des Groseilliers, Marchand, Cordova, Ruzek and Brunet2013) included 70% of the original sample and reported that the intervention was effective compared with controls (p = .008), but findings are interpreted with caution due to a potential sampling bias.

Two RCTs described technology-enabled PTSD prevention. A proof-of-concept trial used a brief Tetris game to prevent intrusive images (Iyadurai et al., Reference Iyadurai, Blackwell, Meiser-Stedman, Watson, Bonsall, Geddes, Nobre and Holmes2017). At 1-week follow-up, intervention participants reported less distress from intrusion symptoms (target symptom) than controls (d = 0.54). Another study used technology to enhance usual care over 6 months (Zatzick et al., Reference Zatzick, O’Connor, Russo, Wang, Bush, Love, Peterson, Ingraham, Darnell, Whiteside and van Eaton2015), which showed modest but non-significant symptom reductions (p = .055) with the greatest effect at 3-month (d = 0.35, p = .044) and 6-month (d = 0.38, p = .044) follow-up. This is an exploratory pilot study, and the results support further research in this area.

The three uncontrolled studies for trauma used exposure for PTSD prevention. A one-session exposure intervention (n = 1) was described as effective as the participant did not report PTSD-related symptoms despite risk factors (Post et al., Reference Post, Michopoulos, Stevens, Reddy, Maples, Morgan, Rothbaum, Jovanovic, Ressler and Rothbaum2017). However, case study results must be interpreted with caution and are not readily generalizable. A further pilot study used three, 1-hour psychoeducation and exposure sessions (Rothbaum et al., Reference Rothbaum, Houry, Heekin, Leiner, Daugherty, Smith and Gerardi2008) reporting a positive but insignificant outcome, but this was limited by a small sample (n = 10). A larger follow-on study (n = 137) (Rothbaum et al., Reference Rothbaum, Kearns, Price, Malcoun, Davis, Ressler, Lang and Houry2012) demonstrated effectiveness in preventing PTSD at 1- and 3-month follow-up (1-month: p = .004; 3-month: p = .05). However, the study was noted as under-powered, risking a type II error.

Panic attacks (n = 5)

No studies met the criteria of RCTs for the treatment of panic attacks. Dyckman et al. (Reference Dyckman, Rosenbaum, Hartmeyer and Walter1999) (n = 354) compared two intervention groups; both received treatment as usual (TAU), a psychiatric referral and a brochure. One of the two intervention groups also received a brief contact with an educator from the psychiatric department or ED personnel offering one 20- to 30-minute anxiety management intervention. This was then compared with a historical TAU control group. There was a statistically significant decrease in ED usage in the brief contact group (p = .0017) in comparison with the brochure-only condition, but not in comparison with the control group (p = .0672). The study does not report on the intervention’s effectiveness, only the impact on ED utilization; this probably reflects selective reporting and demonstrates high risk of bias. Conclusions are limited by this.

Nuthall and Townend (Reference Nuthall and Townend2007) offered a single 45-minute B-CBT intervention for panic or TAU/assessment only (n = 27). Results indicated a non-significant difference in panic severity between groups at 1-month (p = .208) and 3-months (p = .427) follow-up, but the overall sample size was small, and participants were not randomized; hence results can only be considered preliminary.

The Swinson et al. (Reference Swinson, Soulios, Cox and Kuch1992) study active treatment arm consisted of one 60-minute session of reassurance or reassurance plus exposure instruction (n = 33), with the active treatment group benefiting for up to 6 months on all measures including Depression Inventory (F = 7.78; d.f. = 1, 31; p < 0.002), Mobility Inventory (F = 8.56; d.f. = 1, 31; p < 0.002), Fear Questionnaire agoraphobia subscale (F = 6.65, d.f. = 1, 30; p < 0.003) and panic frequency (F = 4.13; d.f. = 1, 31; p < 0.03). Due to unclear reporting, there was a high risk of bias in this study; while this study outlines an intervention study, it does not appear to be reported fully.

Two papers describe the same CBT intervention with different samples: Lessard et al. (Reference Lessard, Marchand, Pelland, Belleville, Vadeboncoeur, Chauny, Poitras, Dupuis, Fleet, Foldes-Busque and Lavoie2011) compared a one session panic management intervention, a seven-session bi-weekly CBT intervention, and usual care for panic disorder and NCCP; Pelland et al. (Reference Pelland, Marchand, Lessard, Belleville, Chauny, Vadeboncoeur, Poitras, Foldes-Busque, Bacon and Lavoie2011) compared a seven-session CBT intervention with medication and usual care. A one-year follow-up study (Marchand et al., Reference Marchand, Belleville, Fleet, Dupuis, Bacon, Poitras, Chauny, Vadeboncoeur and Lavoie2012) reporting both the Pelland et al. (Reference Pelland, Marchand, Lessard, Belleville, Chauny, Vadeboncoeur, Poitras, Foldes-Busque, Bacon and Lavoie2011) and Lessard et al. (Reference Lessard, Marchand, Pelland, Belleville, Vadeboncoeur, Chauny, Poitras, Dupuis, Fleet, Foldes-Busque and Lavoie2011) studies found all interventions to be effective when compared with usual care, but no significant difference between conditions (p = .095). These studies had high risk of bias across most domains, therefore these results cannot be reliably interpreted.

Non-cardiac chest pain (n = 5)

Three RCTs tested the efficacy of CBT to treat chest pain. Tyrer et al. (Reference Tyrer, Tyrer, Morriss, Crawford, Cooper, Yang, Guo, Mulder, Kemp and Barrett2017) compared a modified form of CBT for chest pain (CBT-CP) with standard care. CBT-CP is an adaptation of CBT for health anxiety, including 4–10 sessions over 3–6 months (Tyrer et al., Reference Tyrer, Tyrer, Morriss, Crawford, Cooper, Yang, Guo, Mulder, Kemp and Barrett2017). No significant group differences on any measure were found at either 6 or 12 months, but a reduction was seen in ED attendance; a cost analysis of this change found a non-significant reduction (p = .798) in total costs per patient (Tyrer et al., Reference Tyrer, Tyrer, Morriss, Crawford, Cooper, Yang, Guo, Mulder, Kemp and Barrett2017). The study was reported to be under-powered (n = 68), which indicates a possible type II error. van Beek et al. (Reference van Beek, Oude Voshaar, Beek, van Zijderveld, Visser, Speckens, Batelaan and van Balkom2013) compared TAU with a B-CBT intervention for patients with NCCP who were also diagnosed with depression and panic. The B-CBT consisted of six, 45-minute sessions and was based on Clark’s cognitive therapy for panic disorder (Clark, Reference Clark1986). Using an intent-to-treat analysis at 6-month follow-up, the results showed that CBT was superior to TAU in reducing disease severity on the Clinical Global Impression severity scale (CGI-severity) (p < 0.001). The study has some methodological limitations including a high attrition of 34% after allocation.

Mulder et al. (Reference Mulder, Zarifeh, Boden, Lacey, Tyrer, Tyrer, Than and Troughton2019) reported a well-controlled RCT of a brief intervention based on the biopsychosocial approach termed NCCP directed CBT (n = 424). The intervention included 3–4 sessions consisting of education and self-management for chest pain and reducing cardiac risk factors, compared with TAU. No statistically significant differences were found at either 3- or 12-month follow-up between groups. A statistically significant reduction in health anxiety as measured by the HAI was reported in the intervention group at the 3-month (p < .01) but not the 12-month follow-up; participants who had previously presented with chest pain prior to intervention were significantly less likely to re-present to ED at the 3-month but not the 12-month follow-up, producing an overall temporary gain.

It is noted that while there is conceptual convergence of health anxiety and NCCP, the Health Anxiety Inventory (HAI), as used in both the Tyrer et al. (Reference Tyrer, Tyrer, Morriss, Crawford, Cooper, Yang, Guo, Mulder, Kemp and Barrett2017) and Mulder et al. (Reference Mulder, Zarifeh, Boden, Lacey, Tyrer, Tyrer, Than and Troughton2019) studies, may only be sensitive to changes in the former. Neither paper explored the theoretical rationale or evidence to use the measure, or the potential overlap between health anxiety and NCCP, and may explain the lack of positive findings. The focus of the intervention was also different. Further research is needed to draw consensus of an appropriate measure for use with NCCP; Tyrer et al. reported use of an unstandardized NCCP adapted measure, but reliability is not reported in the paper.

Two quasi-experimental studies used CBT for NCCP. Esler et al. (Reference Esler, Barlow, Woolard, Nicholson, Nash and Erogul2003) compared B-CBT (n = 29) with TAU (n = 30) for NCCP. The B-CBT consisted of an adapted (Barlow et al., Reference Barlow, Craske, Cerny and Klosko1989) 60-minute intervention in the ED for chest pain symptoms (Esler et al., Reference Esler, Barlow, Woolard, Nicholson, Nash and Erogul2003). Statistically significant decreases were found in chest pain episodes, anxiety sensitivity and fear of cardiac symptoms in the CBT group at 1- and 3-month follow-ups (p = .02). However, there were no significant differences in scores on measures of chest pain severity, cardiac-related avoidance or attention. Wilkinson et al. (Reference Wilkinson, Venning, Redpath, Ly, Brown and Battersby2019) reported on an IAPT@Flinders NCCP care pathway for low-intensity CBT (LICBT) in the ED (n = 35). Statistically significant reductions were found for participants who only completed two sessions, with a reduction in scores between the first and second LICBT session on the PHQ-9 (p = .004), GAD-7 (p = .002), and WSAS (p = .004). ED usage data 3 months prior and 3 months post-intervention represented a 59% reduction in ED presentation and a 69% reduction in costs. With a small sample size, convenience sampling, and no control, caution must be taken when interpreting and generalizing the results. NCCP was also not the focus of the intervention. Nonetheless, the reduced psychological distress, ED presentation, and economic costs reported by this pilot study supports further research in this area.

Miscellaneous (n = 3)

One RCT (Katz et al., Reference Katz, Graber, Lounsbury, Vander Weg, Phillips, Clair, Horwitz, Cai and Christensen2017) aimed to support cardiac patients to move towards a healthier lifestyle (rather than symptomatic relief of immediate cardiac symptoms) offering brief or extended behaviour-change counselling. Results did not demonstrate significant differences between treatment arms in longitudinal follow-up. When the results of both treatment arms were combined, patients showed significant differences on cardiac risk factor behaviour-change at follow-up (p < 0.0001), but absence of a control group and combination of two conditions obscures a meaningful or reliable interpretation.

In a quasi-experimental study by Abbass et al. (Reference Abbass, Campbell, Magee and Tarzwell2009), patients with ‘medically unexplained’ symptoms (n = 50) including chest pain, headache, shortness of breath and abdominal pain received a short-term dynamic psychotherapy intervention with a minimum of one session. Improvements were seen on the self-reported Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) (p < 0.01) and a statistically significant reduction in ED usage was reported, with a 69% reduction in ED visits per patient (p < 0.001). However, this study had a high risk of bias and limitations included a lack of a comparison or control group and participant selection bias.

Finally, a single case study using standard CBT to reduce health anxiety in Addison’s disease (Daniels et al., Reference Daniels, Osborn and Davis2017) demonstrated effective outcomes and complete amelioration of ED usage at 1-year follow-up; however, this was not substantiated with business data. The only pre-intervention baseline for comparison was ED attendance rather than distress or physical symptoms, and as this is a case study the results are not easily generalizable.

Acceptability and satisfaction of interventions

All studies were assessed for participant uptake rate, defined as the percentage of eligible patients who consented to participate (see Table 3). Uptake ranged from 45.7 to 100%, with an average of 67.9%; higher uptake rates did not appear to relate to any particular study design or clinical group, but generally speaking smaller studies reported higher end uptake rates, which may be expected given the proportionate ratio.

Two studies measured patient satisfaction ratings for their interventions: Abbass and colleagues report a 93% response rate (n = 13) with overall satisfaction of 7.4 out of 10 (SD 2.1, range 4–10), indicating ‘satisfied/very satisfied;’ for Iyadurai and colleagues the median group values reflected that they found the Tetris intervention very easy (median = 7), very helpful (median = 7) and minimally distressing/burdensome (median = 1), response rate was not reported.

Discussion

Overall, findings reflect that there is some evidence to suggest psychological interventions, particularly CBT, are acceptable and effective at improving pre-defined patient outcomes for adults who attend the ED with physical health complaints as their primary concern. Most studies adopted a broad CBT approach, which is unsurprising given CBT is the recommended treatment of choice for the common ED complaints included in this study, such as NCCP (Chambers et al., Reference Chambers, Marks, Knisley and Hunter2013), panic (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2011), post-traumatic stress disorder (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2018) and those in the miscellaneous category (health anxiety, medically unexplained symptoms, cardiac rehabilitation). Most of the interventions were brief in nature, and while many of the studies included a psychological therapist in intervention delivery, it was evident that CBT based interventions were also being delivered by personnel appropriately trained in the modality.

Given the NHS Long term plan (NHS England, 2019) outlining the projected proliferation of increased access to psychological therapies services, the UK is well equipped to offer psychologically based interventions within the ED, where we know that psychology can effectively reduce healthcare costs (Dr Foster, Reference Foster2018; Holdsworth et al., Reference Holdsworth, Bowen, Brown and Howat2014). These findings suggest acute medical settings may be receptive to brief evidence-based interventions such as CBT, offering a potential avenue for early intervention and prevention of chronicity. However, low-quality designs and high risk of bias within the studies limit the generalizability of many of the findings. Considerable heterogeneity within the studies makes it difficult to definitively refute or confirm overall efficacy of interventions in this setting, particularly as a formal meta-analysis was not viable.

Of those included, 14 out of 20 studies (70%) were completed within the last 10 years, but some (n = 6) studies are more than 10 years old. This reflects a significant paucity of research when broad parameters were defined; as the pressure in the ED increases, with many repeat attenders presenting with psychologically amenable conditions, a call for further high-quality research is needed – services will not develop in its absence. It is important, however, that there is a call to action; even an ‘empty’ review can meaningfully reflect the state of the evidence.

The heterogeneity in study design, outcomes, clinical presentations, and format of intervention was consistent across the clinical groups. The most homogenous group was trauma/PTSD prevention; however, the interventions offered were dissimilar yet appropriately reflective of a rapidly developing field (Iyadurai et al., Reference Iyadurai, Blackwell, Meiser-Stedman, Watson, Bonsall, Geddes, Nobre and Holmes2017). These findings bear some relevance to the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, which has seen emerging research reporting significant trauma responses in frontline staff and post-ICU patients (Daniels et al., Reference Daniels, Ingram, Pease, Wainwright, Beckett, Iyadurai, Harris, Donnelly, Roberts and Carlton2021; Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Daniels, Hulme, Hirst, Horner, Lyttle, Samuel, Graham, Reynard, Barrett, Foley, Cronin, Umana, Vinagre and Carlton2021; Thornton, Reference Thornton2020). Guidelines have been developed to accommodate this surge in psychological need, therefore on-site embedded or accessible psychological care should be considered for both staff and patients (Carroll et al., Reference Carroll, Moss-Morris, Hulme and Hudson2021; Daniels et al., Reference Daniels, Ingram, Pease, Wainwright, Beckett, Iyadurai, Harris, Donnelly, Roberts and Carlton2021).

Average rate of uptake (67.9%) was higher than those reported in IAPT services (56%; Di Bona et al., Reference Di Bona, Saxon, Barkham, Dent-Brown and Parry2014), but this ranged from 45.7 to 100% using a variety of designs. Recent research has indicated that those with long-term conditions may be more receptive to psychological interventions offered within the medical setting (Carroll et al., Reference Carroll, Moss-Morris, Hulme and Hudson2021), which is consistent with the move towards integrated models of care (Damian and Gallo, Reference Damian and Gallo2018). While we cannot compare directly to rates of uptake of psychology following discharge in ED, these rates of uptake are promising and may offer higher rates of engagement to difficult-to-engage groups.

The key conclusion we draw is that findings are promising but further research is warranted; by generating further evidence we potentially offer an avenue of non-invasive intervention for those in distress in high-pressure environments. Future research should seek to address not only the issue of scarcity of research in this area, but also the quality. While heterogeneity is common in areas which feature a paucity of research, there was a common pattern of problems in the study design, outcome measurement and quality of interventions included in this review. On this basis, we offer specific key recommendations which pertain to addressing these issues, in order to strengthen the future research base and allow for more meaningful comparison of studies and outcomes. The use of relevant reporting checklist (e.g. see EQUATOR network) and study pre-registration are also recommended. See Table 5 for a summary of recommendations.

Table 5. Recommendations for future research

Efficacy of CBT for presentations seen in community and out-patient settings is unequivocal (Fordham et al., Reference Fordham, Sugavanam, Edwards, Stallard, Howard, das Nair, Copsey, Lee, Howick, Hemming and Lamb2021; Hofmann et al., Reference Hofmann, Asnaani, Vonk, Sawyer and Fang2012), therefore it is plausible, particularly in light of current findings, to suggest that CBT and other psychological interventions in the ED could prove beneficial and cost-effective. Initiating psychological interventions while in the ED may provide opportunity to overcome post-discharge disengagement, reduce attendances, improve outcomes and offer economic cost benefits (Dr Foster, Reference Foster2018; Holdsworth et al., Reference Holdsworth, Bowen, Brown and Howat2014); however, we must test this further, and do so robustly.

Limitations

Key limitations of this study relate to the broad scope of the search: all study designs were included in order to assess the scope of what is possible in the ED; however, the heterogeneity and relatively small pool derived from the search restricted our understanding even with a broad scope. Evidence provided by case studies is limited, yet these were included as the review aim purposefully encompassed all evidence available in an emerging field. Much of the evidence was poor quality and some more than a decade old – this is a finding in and of itself – so the need for further, better quality research cannot be refuted. By establishing current knowledge our next steps are now with direction.

Conclusions

This review provides preliminary evidence supporting the utility of psychological interventions, particularly CBT, within the emergency department. These are timely findings in the context of a global ED crisis. Given the rapidly expanding availability and strong evidence for psychological therapies in medical settings, provision of CBT-based interventions could offer a feasible and effective alleviation of personal and economic burden. However, further high-quality trials are needed to determine true efficacy and cost-effectiveness of such interventions.

Key practice points

-

(1) Psychological therapy may be feasible and acceptable to patients presenting to the emergency department with physical health complaints amenable to psychological intervention.

-

(2) The use of psychological interventions in emergency care shows some preliminary evidence of improving outcomes for patients in the ED.

-

(3) CBT is the most common intervention trialled within the ED, in line with current evidence and guidelines for the use of CBT and medical conditions.

Data availability statement

The data extraction form, search terms and other supplementary materials defined a priori are available on request. Published papers form the ‘data’ of the present study and can be acquired from the corresponding author on request; the majority are available online.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Dr Samantha Lloyd for acting as second rater for quality assurance purposes and thanks to Sophie Harris and Edward Hirata for supporting the submission process.

Author contributions

Sally McGuire: Formal analysis-Lead, Investigation-Lead, Methodology-Lead, Writing – original draft-Equal, Writing – review & editing-Equal; Mashal Safi: Formal analysis-Supporting, Methodology-Supporting, Writing – original draft-Equal, Writing – review & editing-Equal; Jo Daniels: Conceptualization-Lead, Supervision-Supporting, Writing – original draft-Equal, Writing – review & editing-Equal.

Financial support

The study was funded as part of a Doctorate in Clinical Psychology at the University of Bath.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare none.

Ethical standards

As the study was a systematic literature review, no ethical approval was required. The study proposal was peer reviewed and registered on Prospero database. All authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.