Theatre scholars and historians assume too easily that theoretical reflection on the performative qualities of the theatre began only in the eighteenth century. In mid-eighteenth century France, writers and philosophers such as Denis Diderot, Jean le Rond D'Alembert, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Antoine-François Riccoboni, or Jean-Georges Noverre (to name but a few) showed a passionate interest in the aesthetics and the morality of performance practices in dramatic theatre, music theatre, or dance. Compared to this rich diversity of ideas in the eighteenth century, seventeenth-century French writings on theatre and the performing arts seem, at first sight, far less interesting or daring. However, this is merely a modern perception. Our idea of le théâtre classique is still rather reductionist, and often limited to the theatrical canon of Pierre Corneille, Jean Racine, and Molière. It affords a view of the performing arts that is dominated by tragedy and comedy and that, firmly embedded within a neo-Aristotelian poetics, privileges dramatic concerns above performative interests.Footnote 1

In recent years, theatre scholars like Guy Spielmann and Christian Biet have argued that the theatrical corpus of French classicism should be enlarged, and compared to other performance practices in the ancien régime in order to move beyond this emphasis on the dramatic text.Footnote 2 This move away from a literary perspective is motivated not just by a broadened view on the theatrical event as professed by contemporary theatre and performance studies;Footnote 3 it also finds historical motivation in the seventeenth-century notion of the spectacle. During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, spectacle has acquired a pejorative connotation as mere entertainment that—according to Guy Debord—alienates or even sedates the spectator.Footnote 4 However, in early modernity the notion of spectacle in French (and English)Footnote 5 had a much more general meaning that is often overlooked.

According to seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century French dictionaries, the word “spectacle” refers to a wide range of phenomena. Derived from the Latin spectaculum as something to look at, the early modern notion of spectacle includes not only theatrical representations of different kinds like “operas, plays, ballets, or everything that is to be seen in theatres or amphitheatres.”Footnote 6 According to Antoine Furetière in his Dictionnaire universel (1690), it also refers to public rituals and cultural performances such as royal entries, coronations, and religious, judicial, or military ceremonies and events.Footnote 7 And although there is an emphasis on the spectacle as a visual experience, it equally includes auditory and sometimes even olfactory experiences. Pierre Richelet, in his Dictionnaire françois (1680), writes that spectacle deals with everything that is exposed to the eyes and ears of the spectator.Footnote 8 In the Dictionnaire de l'Académie françoise (1694), we can read that spectacle refers to everything that “arouses public attention.”Footnote 9 This arousal of attention has to do with the fact that spectacle always has something that is larger than life, exceptional, or even excessive and is thus “framed” or set off from everyday life itself. It is this quality that enables the spectacle to produce emotions in the beholder. “A spectacle” writes Furetière in the very first sentence of his definition, “is something extraordinary that astonishes, that one considers with a certain emotion.”Footnote 10 The emotional effect of a spectacle upon the spectator is repeated time and again in late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century definitions of the word.Footnote 11 Even in Diderot and D'Alembert's Encyclopédie (1765), Louis de Jaucourt still emphasizes the affective potential of the spectacle, stating that if a spectacle does not arouse any powerful emotions, does not touch or agitate the heart with exaltation or with devastation, it is hardly worth mentioning.Footnote 12

What is important here is that in early modern dictionaries the word “spectacle” does not refer to a simple or superficial effect, but on the contrary is considered as a multisensorial experience that produces a strong affective response in the spectator. So, the early modern understanding of spectacle has, to a large extent, interesting parallels with the late twentieth-century notion of performance. It refers to a broad phenomenon that is not limited to theatrical representations but includes different cultural performances and actions that, clearly framed as exceptional, exert a powerful and sometimes overwhelming emotional influence over the spectator.

The question here is how to find a valid historical and conceptual framework to understand those strong emotional effects. In 1975, Margaret McGowan proposed looking at the emotional effects of classicist performance practices and spectacle in terms of the sublime. She suggested reading the impact of classicist spectacles not in terms of neo-Aristotelian poetics alone, but relating them also to the increasing influence of Peri hupsous or On the Sublime.Footnote 13 This rhetorical treatise—most probably written in the first century ad by an anonymous author conventionally referred to as LonginusFootnote 14 —is concerned with the question of how the poet or orator can move us deeply, how their writing or speech can elevate, astonish us, or can transport us beyond our subjectivity. Although McGowan's attempt to interpret the impact of classicist spectacles from the perspective of the sublime was definitely pioneering in that it exchanged analysis in terms of poetics for an approach in terms of effects, it was only a tentative move; in the early 1970s research into the seventeenth-century sublime was still in its infancy.

Interest in the early history of the sublime attracted increasing scholarly attention, leading in the 1980s to a series of publications and research programs that studied the dissemination and reception of the Longinian sublime in early modernity. These revealed how the sublime played an ever more important role in the creation, and more particularly in the sensuous appreciation, of the arts. As such the early modern reception of Longinus’ treatise appears then as a prelude to the emergence of aesthetics in the eighteenth century. Ann Delehanty, in a recent and daring article, even proposes that the birth of aesthetics happened not so much in 1750, with Alexander Baumgarten's Aesthetica, but earlier—with the essential move from poetics and rhetoric to aesthetics, or “from judgment to sentiment,” occurring at precisely the moment when the second half of the seventeenth century rediscovered the importance of the sublime.Footnote 15

In this article we take a closer look at the notion of the sublime and how early modern French writings on the history and function of spectacles used the concept to discuss the effects of spectacles as forceful, multisensorial experiences. In the first two sections of the article, we focus on the recent and changing scholarly interest in the seventeenth-century sublime and how this notion can be seen as a fruitful concept to discuss the overwhelming effect of the arts. The seventeenth-century notion of the sublime can be understood here as a strong “presence” effect that establishes a deep communication between a representation and its beholder, and for which the performing arts acted as a privileged model. In the second and third groups of sections, we look deeper into how the sensuous effects of spectacles are theorized in the writings of Michel de Pure and Claude-François Ménestrier. Both use the sublime, and what we call “neighboring” concepts such as magnificence, le-je-ne-sais-quoi, and le merveilleux, to understand the effects of spectacle in terms of “presence,” in the sense that it overwhelms, transports, or elevates the spectator and for a short moment abolishes the gap between reality and representation. By using those concepts to describe the powerful sensuous effects of spectacles, De Pure and Ménestrier show that, contrary to what is too often assumed, theoretical and aesthetic reflection on theatre and performing arts did not start in the eighteenth century with Diderot and others. It began almost a century earlier in a rich discourse on the nature and the effects of spectacle.

Early Histories of the Sublime

Outside the field of early modern studies, it is still often believed that the sublime only reappears in modern criticism with Nicolas Boileau's Traité de sublime; ou, Le merveilleux dans le discours in 1674, and that it functions there as a specific literary concept. Boileau's text is indeed the first full-length French translation of Longinus’ treatise. The importance of the Longinian sublime, as Boileau explicitly states in his influential preface to the translation, resides in the fact that the sublime is not considered as a mere question of style (the genus grande or genus sublime), but as the effect of speech:

It must be observ'd then that by the Sublime he [Longinus] does not mean what the Orators call the Sublime Stile, but something extraordinary and marvellous that strikes us in a Discourse and makes it elevate, ravish and transport us.Footnote 16

This sublime effect of speech, as Emma Gilby writes, can be understood in terms of an encounter among an author, a work of art, and an audience. On the one hand, due to vividness in speech it makes the reader/listener forget the representational aspect of language, turning him/her into a witness to the event that is described. On the other hand, it is precisely this quality that creates the audience's admiration for the author or orator. In that sense, the sublime can be seen as producing, for the reader or listener, a movement or an elevation toward an author or an orator via a text.Footnote 17

Despite Boileau's importance in the history of the sublime, he was not the first early modern author to discover the possibilities of Longinus’ text. In recent decades scholars have discussed in detail how, after its rediscovery in the mid-sixteenth century, Peri hupsous fueled seventeenth-century poetical discussions in France (and elsewhere) on the overwhelming and transporting effect of literature.Footnote 18 Within these French discussions on the sublime prior to Boileau's translation, there are two important elements to take into consideration.

First, Longinus’ ideas on the overwhelming and transporting effects of literature throw into question the understanding of the relationship between genius and poetical technique that had been established by neo-Aristotelian and classicist poetics. Longinus shows authors that sublime literature can be achieved by ignoring poetical restrictions, making mistakes and breaking rules. The overwhelming effect of literature is then not so much part of a technè, but is above all produced by the mysterious and forceful working of genius. According to Longinus, the two most important sources of the sublime are the capacity to conceive great thoughts and the compelling treatment of emotions. They are innate qualities and cannot be learned, but are indispensable for creating an overwhelming and transporting effect in the reader.

Modern critics have often overlooked this debate of rules versus genius in French classicism and the important role of Longinus within it. They have presented classical doctrine through the persistent but simplified image of a unified and rational system of rules, a kind of poetical offspring of the Cartesian idées claires & distinctes, in which there seemed no place for Longinus and his plea for genius.Footnote 19 This traditional image of French classicism was only widely revised in the 1980s, especially with the influential writings of Marc Fumaroli. Time and again he emphasized the importance of the Longinian sublime for the humanist Republic of Letters and for the formation of classical doctrine. He even suggested that, especially in this debate of rules versus genius, Peri hupsous operated throughout the seventeenth century as a kind of shadow text to Aristotle's Poetics.Footnote 20

Second, the seventeenth-century use of the sublime is not necessarily limited to the domain of literature or discourse alone. It has a much larger scope. The sublime does not operate here as a strictly codified concept, but is much more fluid and often operates within a network of other concepts. The sublime's effect of elevation bears similarities with the political notion of magnificence; its astonishing character is often explained in relation to the artistic and religious notion of le merveilleux; while its mysterious and inexplicable nature is often paired with what the Jesuit Dominique Bouhours described as le-je-ne-sais-quoi. Due to those varieties in the concept's meanings and scope, the most recent scholarship on the sublime in the seventeenth century suggests a rethinking of the sublime from an intermedial perspective that attends to overwhelming and transporting experiences of multiple kinds, be they in literature, in the visual arts, in religion, in science, or in the experience of nature.Footnote 21

This broader approach makes perfect sense especially for the visual arts. Strongly embedded within the doctrine of ut pictura poesis, painters, sculptors, and architects used poetical and rhetorical concepts to theorize and describe the strong effect and agency of art. In Translations of the Sublime, a recent collection of essays to which we both contributed, the task set was to look at how the sublime clearly acts as a concept that travels from rhetoric and poetics to the visual arts, and how it interrelates with other concepts to define and explain the overwhelming experience of artworks.Footnote 22

Spectacle and the Sublime

But what about the performing arts and the sublime? In thinking about dramatic theatre, literary critics made the connection with the sublime at an early stage, although exclusively at the level of the dramatic text. In the 1630s, Corneille's tragedies had already been described in terms of the sublime. Short phrases, such as old Horace's “Qu'il mourût” (Horace, act III, sc. 6) or Médée's “Moi, moi, dis-je et c'est assez” (Médée, act I, sc. 5) became famous examples of how speech can engender a sublime experience in the spectator, the listener, or the reader.Footnote 23

However, little work has been done on the effects of the performing arts and its relation to the sublime.Footnote 24 Here, another set of possibilities should be investigated in which the notion of presence and its effects is of particular significance. As Marc Fumaroli writes, seventeenth-century interests in the sublime are often articulated around the sublime's potential to abolish the gap between presence and representation. The sublime seems to transform language into a living creature, establishing in the reader or listener images or phantasiai that have a profound and irresistible effect of presence.Footnote 25 This sublime effect of presence is built upon two important strategies from classical rhetoric: enargeia and ekplexis.

In classical rhetoric enargeia (in Latin, illustratio) is one of the most important instruments of persuasion. Etymologically derived from argès or shining light, enargeia means clarity, distinctness, and vividness. In the context of rhetoric and literary criticism, it points to a vivid or lifelike description by which the reader or listener forgets it is a representation, but sees the thing or person described before his or her own eyes. Enargeia, as Longinus states, is always dependent on pathos or emotional involvement, for the author as for the listener or reader. In order to create a vivid description the author must have seen the thing he describes.Footnote 26 Due to this emotional involvement the author creates strong images in his own mind that he can awake in the mind of the beholder.Footnote 27 Enargeia signals thus an effect in which the representation dissolves into the thing represented. It is built on a suspension of disbelief that makes absent things present in the mind of the author and reader or listener through the vivid effect of representation.Footnote 28

According to Longinus, the sublime effect of presence draws not only on enargeia but also on the notion of ekplexis, or an emphasis on the captivating force of the sublime. Ekplexis is derived from ekpletto, which means to strike, confound, paralyze, or render somebody beside themselves with wonder, amazement, and fascination. Whereas enargeia signals the vivid effect of the sublime, ekplexis deals more with its sudden effect that catches and holds the attention of the beholder as a kind of violent surprise that can often evoke fear.Footnote 29 By its suddenness and its feeling of fearful surprise, ekplexis also obliterates the demarcation line between fiction and reality, creating in the reader or listener the effect of witnessing directly or even being physically and emotionally involved in the situation described.

This effect of presence through vividness and terrifying amazement is also crucial to understand the impact of spectacles on the spectator. One might go further to say that, since antiquity, the performing arts have functioned as the paradigm for this effect of presence. Aristotle, in his Rhetoric, writes that the effect of presence is most powerfully achieved when things are literally acted out by the orators in front of an audience. Those orators, he writes, “who contribute to the effect by gestures, voice, dress, and dramatic action generally, are more pitiable; for they make the evil appear close at hand, setting it before our eyes.”Footnote 30 In early modern treatises on spectacles, the liveness of the performing arts is time and again presented as the best way to create this effect of presence. Through their live character spectacles function as “moving images” or “peintures parlantes” that can bring back distant pasts, revive the dead, and even embody the most abstract ideas and thus create this effect of vividness. At the same time, as we have seen in early modern definitions of the spectacle, they also draw on this notion of ekplexis without which they could not exist. As we've noted, Furetière wrote in his definition, “a spectacle is something extraordinary that astonishes, that one considers with a certain emotion.” They need this captivating moment to arouse the attention of the spectators and to evoke in their minds and senses strong and overwhelming impressions that transport them beyond themselves. As we shall see, it is exactly in this combination of vividness and breathtaking astonishment that Abbé de Pure and Claude-François Ménestrier situate the sublime potential of early modern spectacles. Both authors theorize the spectacle as a powerful motor in the creation of strong and overwhelming affective responses.

De Pure's Idées des Spectacles

Michel de Pure (1620–80) was chaplain and historiographer to Louis XIV. He wrote novels and plays for the theatre, and translated Quintilian's Institutio Oratoria and Giovanni Pietro Maffei's Le istorie dell'Indie Orientali (as Histoire des Indes); but he is best known for his Idées des spectacles anciens et nouveaux (1668). In this treatise he uses the term “spectacle” in its widest sense, as Richelet and Furetière will do some years later. De Pure refers to a rich diversity of ancient spectacles, such as Roman gladiatorial games, triumphs, and naumachiae (mock sea battles), as well as to modern spectacles such as carousels, fireworks, masquerades, comedies, tragedies, and ballets. De Pure is not so much concerned with the poetics of these different spectacles; he is far more interested in the sensuous (above all, visual and auditory) effects they produce on the spectator and how they create a feeling of astonishment. He even considers the spectacular effects in performance more important than regularity in plot or subject. He describes them as “theatrical substances that can stand on their own and that all by itself can charm the senses & strike the imagination.”Footnote 31 This sensuous effect of performance is thus not necessarily superfluous, as so many classicist critics such as d'Aubignac and even Corneille had suggested. If employed well, spectacles can have an enduring and forceful effect on the beholder that makes them more then mere entertainment or “divertissement.” As De Pure emphasizes time and again, ancient and modern spectacles even support social cohesion and function as an important instrument of power.

In his prefatory remarks addressed to Louis XIV, De Pure situates the meaning and function of spectacles at a political level. Spectacles are the privileged media for the public display of royal power; De Pure even relates them to the king's politics of war, portraying them as the avant-goûts of future victories or as vehicles for securing the afterlife of Louis's successes on the battlefield (“Au Roy,” n.p.).Footnote 32 Spectacles serve as performative instruments by which the monarch publicly displays, establishes, and ensures his royal power. As such, they reach a level of importance that makes them worthy of the “sublimes pensées” or elevated thoughts of Louis XIV (ibid.). In his treatise De Pure never mentions Longinus explicitly, so we cannot speak of a direct influence here. However, his use of the word “sublime” clearly corresponds to two neighboring concepts that are closely related to the Longinian sublime: magnificence and le-je-ne-sais-quoi.

Spectacle as Magnificence

Like his contemporaries, De Pure no longer uses the word “sublime” in terms of the eloquent or grand style. He uses it to define a certain quality and an effect associated with the elevated status of the king and the magnificence of royal dignity. Longinus himself had already often paired hupsous—literally, “heightened state”—with megaloprepeia (magnificence, majesty), while the Latin notion of magnificentia as “doing something great” (magnum facere) was seen as a moral quality attributable to heroes and leaders. In Renaissance political and iconographical tradition, magnificence becomes more and more the glorious and imposing quality of royalty. The relation between the sublime and magnificence becomes even more apparent in an incomplete and anonymous mid-seventeenth-century French translation of Peri hupsous, made by someone in the close circles of Cardinal Mazarin. Here, magnificence functions literally as a synonym for the sublime, giving the sublime a political valence that suggests the enormous and overwhelming power of royal sovereignty.Footnote 33

This connection between the sublime and magnificence also means that magnificence is more than a quality that defines the grand, the elevated, and the infinite. It also means that it is considered as an experiential category. Like the sublime, magnificence generates an overwhelming and astonishing experience. It establishes an almost physical contact between the king and his subjects. According to De Pure, spectacles can play an important and privileged role in creating this elevated communication. They serve as media that communicate the magnificence of the ruler and bring him close to his subjects by means of overwhelming effects.Footnote 34

The astonishing and communicative effect of spectacles is particularly to be seen in ancient and especially in Roman triumphs. De Pure considers those spectacles to be the most superb expressions of magnificence, evoking as they do the greatest admiration in the spectator (111–12). He relates the triumph etymologically to the Greek thriambos, or hymn to Dionysus. Like the hymns and dances (dithurambos) in honor of Dionysus, the Roman triumphs excite in the viewer “an exultation or an enormous joy” (112–13). The ancient triumph functioned as a public ritual in which the citizens felt themselves to be participating in the glory of the triumphant general (130).

This exultation is achieved by the abundance, the enormous opulence, and the multimediality of the spectacle. Instrumental music, for instance, framed the beginning of the triumphant march and excited joy and exultation in the spectators (132), while a thousand songs accompanied the triumphal wagon to enhance public acclamation (144–5). Further, the procession presented spoils and statues, such as idols and cult objects, thus evoking great admiration for the general who had acquired them (134–5). And to make sure the public comprehended the importance of the victory, large paintings or scale models of the events were also presented during the procession (132–4). In their extreme artistry and vividness those models and paintings transformed the Roman public into witnesses of the event depicted, and thus increasing their involvement (133). This ritualized moment of contact between the Roman citizens and the magnificent general and his victorious battle reaches its peak as the general passes by, standing on a triumphal wagon of ivory and gold. To emphasize the union among the general, his military actions, and the audience, drops of blood would be showered over his wagon and the spectators (114, 128).

De Pure's description of Roman triumphs exhibits a remarkable correspondence with Charles Le Brun's Entrée d'Alexandre dans Babylone (1665) (Fig. 1). Painted at the height of the Alexander cult of Louis XIV, we see Alexander's triumphal entry into Babylon after his victory over the Persian king Darius. Standing on a radiant ivory chariot with gilded decorations depicting battle scenes, Alexander is presented here as the victorious general exemplifying the imperial union between potestas (military and judiciary power) et auctoritas (spiritual or moral, almost mysterious authority). Surrounded by mythological and historical figures and by spoils and statues seized from the Persians, the triumphal entry is presented as a multisensorial spectacle. It enchants not only the eyes and ears but even plays on olfactory experience, through its use of smoke and burning ashes, to impress and involve the audience to a maximum.

Figure 1. Engraving (1675) by Girard (aka Gérard) Audran (1640–1703) of Charles Le Brun's Entrée d'Alexandre dans Babylone (1665). Ghent University Library, Kostbare Werken, BHSL.RES.1323 (Audran, Girard). (The engraving is a mirror image of Le Brun's painting.)

Spectacle as Mystery: Le-Je-Ne-Sais-Quoi

De Pure signals how the magnificence of the Roman triumphs is inscribed within a religious and ritualistic context, which lends the entire ceremony a sense of mystery and seriousness that astonishes and overwhelms the viewer (112, 144–8). Accentuating the mysterious and impenetrable qualities of true magnificence also elevates it beyond rational or logical explanation. In De Pure's idea of spectacles, it is precisely this sense of mystery that becomes the ultimate goal of spectacles. Although he accentuates this sense of mystery in Roman triumphs, he sees them just as clearly in modern spectacles such as royal entries, carousels, fireworks, and naumachiae—and, in his view, even tragedy, comedy, and ballet cannot do without it. He considers the effect of spectacles as a “je ne sçay quoy” that is “more perceptible then explainable” (290). It is here that De Pure's interest in the magnificent effect of spectacles meets with the more general concept of le-je-ne-sais-quoi. It shows us how ideas on the effect of spectacles do not occur in isolation, but participate in a larger framework of intellectual and artistic debates.

Although the notion of le-je-ne-sais-quoi had already entered French criticism at the end of the sixteenth century, and referred broadly to the inexplicable effect of an event, a person, a phenomenon, or a representation, it was only with the Jesuit Dominique Bouhours that it was theorized more extensively.Footnote 35 In his Entretiens d'Ariste et d'Eugène (1671), Bouhours defines le-je-ne-sais-quoi as a purely experiential category that can never be fully explained, and that therefore functions as a kind of mystery:

It is for sure that le je ne sçay quoi is in the nature of those things that can only be known through the effects they produce. … Its price & its advantage consist in being hidden.Footnote 36

Le-je-ne-sais-quoi resides not only in its secrecy and mystery, but equally in its immediacy. It is a purely sensuous, experience that strikes the viewer and produces a inexplicable feeling “that surprises & that transports the heart at first sight”’ and “that dazzles us & that enchants us.”Footnote 37 Bouhours's notion of le-je-ne-sais-quoi comes close here to the notion of the sublime as Boileau understands it in his translation of Longinus. The two concepts are similar in accentuating the mysterious, immediate, and transporting effects they produce. The difference, however, lies in the their scope. Whereas Boileau restricts the sublime to discourse, Bouhours's notion of le-je-ne-sais-quoi encompasses much more. It can be found in calm and stormy seas, or in great rivers and silent forests; it belongs also to painted or sculpted figures that seem almost to be alive, and in which only speech is missing.Footnote 38

Bouhours also relates le-je-ne-sais-quoi explicitly to magnificence and to spectacle. He defines magnificence as an indispensable moral quality and as a political instrument of the prince. In the third Entretien, “Le Secret,” he states that the prince's authority and grandeur are always built upon its secretive mysteriousness and can never be unveiled.Footnote 39 Within this mysterious magnificence of the prince, spectacle has a privileged role. It serves as a public display of power and testifies to the monarch's grandeur, which in itself is a divine imprint. This spectacularization of royal power, particularly in the case of Louis XIV, gives the king a revelatory force. His appearance in ballets or carousels, writes Bouhours, is all that is needed for him to be recognized and to overwhelm.Footnote 40

Similarly, De Pure puts spectacle at the service of the display of royal mystery. Whether he writes about ancient spectacles or modern fireworks, tournaments, carousels, royal entrances, comedy or ballet, De Pure's main focus is upon spectacles as vehicles for expressing the elevated status of the ruler, and upon how they are able to astonish the beholder. They create “une exultation & pleine ioye” that cannot be fully explained but that nonetheless imprints the mind with powerful, lasting, and beautiful images. As such, le-je-ne-sais-quoi of magnificent spectacles gives them a quality of ekplexis, in the sense that they strike and overwhelm the beholder. At the same time, spectacles require vividness in order to strike and captivate the imagination. It is in this combination that the spectacle can function as a kind of presentification machine by which “one brings back the most distanced times, one makes revive dead persons or one gives body to the most abstract of ideas” (212–13).

Although Michel De Pure may not refer explicitly to the Longinian sublime, his enduring interest in spectacle as a locus for communicating and mediating the magnificence of the king bears remarkable similarities to Longinus’ understanding of the sublime as a form of elevated and inspired communication. It also reveals how the emergence of the sublime in seventeenth-century theory corresponds with neighboring concepts such as magnificence and le-je-ne-sais-quoi, and interacts with a much wider interest in the overwhelming and transporting effects of spectacles as part of French absolutist cultural policy.

Mediatization and Institutionalization of the Spectacle

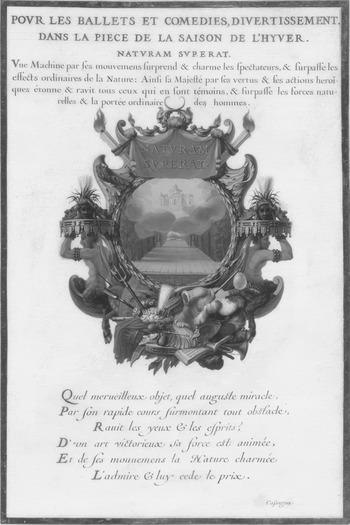

The importance of spectacles as instruments of royal propaganda can be seen by the fact that not only do they function as mediators of royal sovereignty, but that spectacles become the object of mediatization themselves. In writings, in prints and paintings, in tapestries, or in emblems and devises (devices or mottoes) that were orchestrated by the Petite Académie (officially, L'Académie royale des inscriptions et médailles), attention is frequently paid to the political importance of spectacle. In the famous series of tapestries Les Quatres Élémens et les quatres saisons designed by Charles Le Brun in the mid-1660s, spectacles are depicted as one of the main divertissements of king and court. In the accompanying Devises pour les tapisseries du Roy (1668), spectacle and king are even more closely connected.Footnote 41 In the penultimate devise of this collection (Fig. 2), the figure or “corps” represents a stage set of a baroque perspectival garden with a descending palace in the middle.Footnote 42 The soul or “âme” of this devise bears the inscription naturam superat, meaning that spectacle surpasses nature. The meaning of text and image is exemplified in the epigram above. Importantly for our argument, the surpassing and astonishing effect of the spectacle is here literally equated with the overwhelming effect of Louis XIV himself, with both explained as miracles or irresistible epiphanic experiences:

A Machine, by its movements, surprises & charms the spectators, & surpasses the ordinary effects of Nature: Similarly, his Majesty, by his virtues & heroic actions astonishes & ravishes all those who witness them, & surpasses the forces of nature & the ordinary reach of men.Footnote 43

Figure 2. Devise XXXI in Devises pour les tapisseries du Roy (1668), with the inscription naturam superat, shows a stage set of a garden with a descending palace. BnF, Estampes et photographie, Rés AA-6.

In the madrigal beneath, the king's heroic actions are again compared to the effect of spectacles. In a language similar to the sublime, the king's elevated status and his ravishing, astonishing, and transporting effect are accentuated as an “august miracle.”Footnote 44

The importance of spectacle as an instrument of absolutist cultural policy became particularly apparent in August 1674. Henri Guichard, the “intendant des bâtiments et jardins” of the king's brother, obtained from Louis XIV a patent letter to erect an Académie royale de spectacles. The goal of this new Académie was to control the organization of public spectacles as a form of entertainment and to make sure they provided sufficient and appropriate occasions for praising the king. The patent granted the exclusive privilege to “construct circuses and amphitheatres in order to organize carousels, tournaments, races, jousts, battles, animal fights, illuminations, fireworks, and generally everything that can imitate the ancient games of Greeks and Romans.”Footnote 45 Although this Académie was never realizedFootnote 46 it shows the attempt to institutionalize public entertainment for political as well as for pedagogical purposes, and may well have been inspired by De Pure's ideas on spectacles and their potential to evoke a “sublime” experience in the hearts and minds of spectators.

Ménestrier and Spectacles as Images d'Action

The Jesuit Claude-François Ménestrier (1631–1705) was the prolific author of numerous theoretical and historical treatises on heraldry, emblems, and devises, enigmas, and especially on diverse spectacles, such as ballet, musical theatre, and tournament. Although his writings are often more enthusiastic and long-winded than intellectually and theoretically rigorous, Ménestrier provides an extremely rich comparative source on courtly spectacles in seventeenth-century Europe.Footnote 47

Moreover, Ménestrier considers spectacles as important agents in his Philosophie des images, which forms the theoretical basis for all his writings. This philosophy of images is, as Ralph Dekoninck states, profoundly theological and anthropological, fusing Catholic and Aristotelian ideas on mimesis as the basic condition of man.Footnote 48 The effect of images has here an epistemological, sensitive, and creative quality. Thanks to the imprint of images in the mind, humans can make their world intelligible, but the agency of images has an energetic force as well. It affects the senses deeply, and results in a creative act. Humans tends to create in their own images, repeating or reenacting the example of the Creator.

This effect is especially true for spectacles, which Ménestrier defines as multimedial images d'action and which he sees as the most powerful agents in his philosophy of images. Spectacles, as living and moving images, have a unifying and communicative force, thanks to their vividness, and invite the spectator to incarnate the image.Footnote 49 In this rhetoric of vividness, images regulate and inspire an encounter between what is represented and the spectator that is very similar to the transporting experience of encounter or fusion considered by Longinus to be sublime. Jesuits were among the first to recognize the importance of Peri hupsous as an instrument to conceptualize the communicative and moving possibilities of the arts and to include this as an important part in their educational program.Footnote 50

This is also the case for Ménestrier, who uses Longinus in a much more substantial way than does De Pure to demonstrate the overwhelming effects of spectacles. He had already mentioned Longinus in his very first theoretical treatise, L'Idée de l'estude d'un honneste homme, a never-published set of lecture notes from 1658.Footnote 51 In this manuscript he describes the ideal library for the honneste homme, and refers to Peri hupsous as an indispensable book when it comes to rhetoric.Footnote 52 However, Ménestrier gives Longinus no further attention in these notes.Footnote 53

Ménestrier's interest in Longinus increased from the late 1660s onward, something in which the prestigious Académie de Lamoignon must have played a part. This private academy existed from 1667 to 1677 and was founded by Guillaume de Lamoignon, the first president of the Parliament of Paris. This closed circle of intellectuals and scholars—which included, among others, Boileau and Bouhours—was of particular importance in the history of the sublime. First, Lamoignon was a patron of Tanneguy le Fèvre, who edited a Greek edition of Peri hupsous in 1663. Second, parts of Boileau's translation circulated there from the late 1660s onward.Footnote 54 Ménestrier attended and participated in the debates of the Académie, at least between 1667 and 1669, and must thus have been aware of the growing interest in Longinus.Footnote 55

Despite this early acquaintance of Ménestrier's with Longinus, it is another decade before he uses the Greek author in a more substantial way, namely in his Des représentations en musique anciennes et modernes (1681). In this fascinating and extremely rich discourse on the history and objectives of musical spectacles, he draws up a genealogy of contemporary opera that finds its origins in Greek and biblical examples and discusses how musical spectacles can produce powerful affective and transporting effects in the minds of the spectators.Footnote 56 In this text, references to Longinus can be found in three contexts: first, as regards the effect of music; second, in his discussion on the sublime effect of painting; and third, regarding the question of whether multimedial spectacles should be subjected to poetical regulations or left to the creative imagination of genius in order to excite a feeling of wonder.

Ménestrier and the Musical Sublime

In explaining the capacity of musical spectacles to move and transport the audience, Ménestrier explicitly mentions Longinus in the chapter on the effects of music in ancient Greece.Footnote 57 He refers to Chapter 39 of Peri hupsous—which he quotes in its entirety from Boileau's translation—in which Longinus compares the arrangement of words with harmony in music, and its capacity to excite passion and exultation in the listener. The music of flutes and harps, writes Longinus, “induces certain emotions in those who hear it” and can carry them away as though they were out of their minds and “fill[ed] … with divine frenzy.” By the variety of their sounds and by the harmonious blending of their tones, these instruments “often exercise … a marvellous spell.” Composition in language, states Longinus, is a kind of harmony in words and has the same effect. It stirs “myriad ideas of words, thoughts, things, beauty, musical charm,” which, blended together, transport the emotion of the speaker into the mind and the heart of the listener.Footnote 58 Longinus uses a musical metaphor to explain the importance of composition in language in creating sublime effects. This effect can be achieved only by means of a total harmony. Harmony, however, should be understood here not simply in terms of order and calmness, but rather as the overall effect of composition in which every single element contributes to the proposed effect.

Although Longinus considers harmony in music as exemplary for sublime speech, this does not mean that he ascribes to music itself the same, strong affective responses as he does to words. Longinus explicitly states that the emotive power of music is “only a bastard counterfeit of persuasion.” For the listener, it is not as strong as harmony in words, which “reach not only his ears but his very soul.”Footnote 59 The pathos of music may be genuine and forceful, but it is merely analogous and subsidiary to the overwhelming effect of words, which alone can be truly sublime.Footnote 60 This nuance is also present in Boileau's translation as cited by Ménestrier.Footnote 61 Interestingly, however, Ménestrier pays no attention to this distinction and places the analogy between harmony in music and composition in language on the same level, stating that both are able to produce sublime effects: “Can one doubt, after such an explicit testimony made by such an enlightened man, that the Greeks did not have a Music that was capable in producing such grand effects?”Footnote 62 Here, not only does the sublime move away from discourse into the field of music, but in doing so it acquires a new freedom, liberated as it is from some of the formal restrictions imposed upon it in the field of poetry.Footnote 63

Ménestrier and the Pictorial Sublime

There is also a second reference to Longinus in Des représentations en musique where Ménestrier focuses extensively on the relation between music and painting, arguing that both can have a similar emotionally overwhelming and purely sensuous effect on the beholder. For the ancients, painting, like music, was never “a simple representation … that causes admiration in the mind, without the heart and the senses took part in it.”Footnote 64 The emotive quality of painting is not limited to Greek painters alone, but is also present in, and even surpassed by, two contemporary French painters, Nicolas Poussin and Charles Le Brun. Whereas Ménestrier mentions only Poussin briefly,Footnote 65 Le Brun is given more attention, and is lauded with a sonnet with implicit, but clear references to Longinus:

Of course, Ménestrier refers here to Le Brun's fame as a painter of the passions. But that is not what makes him a sublime painter. According to this sonnet, Le Brun is especially sublime for having overcome the limits of his own medium. In his use of light and shade, he makes figures appear to be coming out of the canvas, approaching the spectator, and he is even able to make the soul visible or to paint and express what the eye cannot see.

This transcendence of the limits of painting is remarkably close to what Longinus sees as a fundamental aspect of the sublime in rhetoric, and which consists in the correct use of figures of speech to create the illusion of presence. A figure of speech is most effective when it “conceals the very fact of its being a figure.” An “all-embracing … grandeur” must obscure all rhetorical devices.Footnote 67 In painting, Longinus writes, we see something of the same kind:

Though the highlights and shadow lie side by side in the same plane, yet the highlights spring to the eye and seem not only to stand out but to be actually much nearer. … What is sublime and moving lies nearer to our hearts, and thus, partly from a natural affinity, partly from brilliance of effect, it always strikes the eye long before the figures, thus throwing their art into the shade and keeping it hid as it were under a bushel. Footnote 68

According to Ménestrier's sonnet, Le Brun masters this strategy of highlighting so well that he distracts the attention of the beholder from the skill of the artist by means of the enthralling effect of imagination. The painter is able to conceal the representational character of painting in a “halo of brilliance,” as Longinus puts it. It is precisely this ability that makes him able to render the passions most convincingly, to make the soul visible and even—paradoxically—to express in painting what the eye cannot see.Footnote 69 As such, he achieves one of the main characteristics of the sublime according to an early modern understanding: turning the representation into a most vivid presence. This vivid presence has a striking and ekplectic force as well in the sense that it works like a revelation: like Saint Paul in his ecstasy, Le Brun ascends to the most sublime of heavens. But unlike Saint Paul, who does not reveal the mystery, Le Brun seems to go one step further. By “painting” or visualizing the mystery he unveils it or makes it present in the mind and the heart of the beholder.

At first sight, Ménestrier's discussion of the sublime effect of music and painting seems to stand on its own and to have little to do with musical spectacles itself. Nonetheless, we should not forget that his comments on music and painting should be read as reflections on the constituent parts of musical spectacles. As we have seen, he considers musical spectacles as “images d'action” that make use of different media (music, dance, visual arts) to affect the beholder. In his preface, he had already accentuated the multimedial aspect of musical spectacles, stating that it is exactly because of this multimediality they “express so naively the affections of the soul & produce so agreeably the painting of our morals.”Footnote 70

Beyond Regulation: The Marvelous Effect of Spectacle

This multimedial character of musical spectacles also implies that they are not so easily inscribed within a fixed set of rules such as those of tragedy or comedy. They escape purely poetical regulations, or at least, they cannot be judged in such terms. Musical spectacles are entirely left to “the genius, the imagination and the experience of those who have to invent them.”Footnote 71 With this preference for genius over rules, Ménestrier touches here again on what in the seventeenth century had become a topos in the reception of Longinus. As we mentioned earlier, Peri hupsous can be considered as a shadow text to Aristotle's Poetics, especially when it comes to the debate over nature, genius, and rules. In chapter 33 of Peri hupsous Longinus deals with the fact that truly great authors or orators such as Homer or Demosthenes often defy the regulations or make apparent mistakes. Longinus considers this genial “negligence” a proof of their sublime minds.Footnote 72 This tension between genius and rules, or even warning against poetical overregulation, is repeated time and again in the seventeenth century, and Longinus appears here as the main authority.

Seventeenth-century critics and advocates of regular tragedy, such as d'Aubignac and later Racine, often considered this lack of rules in musical spectacle as a sign of their inferiority. But as Ménestrier argues throughout Des représentations en musique, musical spectacles do not seem to affect the audience by means of a dramatic structure that carefully links one scene with another, within a logic of vraisemblance. Far more important than the coherence and concentration of the dramatic plot is the purely sensuous effect of this multimedial genre. The combination of different media surpasses the singular effects of music, dance, text, and painting. They address several senses at once and in so doing excite in the spectators a feeling of the marvellous, or le merveilleux, that transports and ravishes them but that can never be captured in a set of rules.

Ménestrier's preference for genius over rules is exemplified in the many and sometimes exhaustive descriptions of overwhelming spectacles. Contrary to what one might expect, he does not focus on the recent successes of the tragédie lyrique from the mid-1670s. By the time Ménestrier wrote his Des représentations en musique, Quinault and Lully had already subordinated French opera to the dramatic logic of vraisemblance and tempered the spectacular extravagance of the genre, turning it into a worthy musical version of French tragedy.Footnote 73 The examples Ménestrier highlights date mainly from a previous period, namely from the late 1640s to the 1660s when Italian opera made its way to France and created a vogue for musical spectacles with elaborate and overwhelming machinery. He comments often on the first Italian operas performed in France, such as Giulio Strozzi's La finta pazza (in 1645), Luigi Rossi's L'Orfeo (in 1647), and Francesco Cavalli's Ercole amante or Hercule amoureux, which was performed for the opening of the new Salle des machines in the Tuileries Palace in 1662. Additionally, he gives detailed comments on operas, feste teatrali, and other musical spectacles in Italy, Germany, or Savoy, mentioning how they all descend from courtly festivals such as those of the Medici in Florence and the tradition of joyous entries in the Netherlands. With this mix of undefined genres and examples, Ménestrier clearly takes a stance against the overregulation of contemporary French opera, and instead proposes to see it as part of a wider European tradition of (musical) spectacles. It is there, and not in a clearly defined poetical system, that there emerges the idea that its marvelous effect depends primarily on its spectacular nature.Footnote 74

The notion of le merveilleux as used by Ménestrier is very similar to both the sublime and le-je-ne-sais-quoi. Boileau used le merveilleux as the major synonym for the sublime, whereas Bouhours sees it as an effect of le-je-ne-sais-quoi, causing “astonishment and pleasure altogether.”Footnote 75 Ménestrier, who was well aware of the discussions on the overwhelming and transporting effect of art in the Académie de Lamoignon, seems to have sought a similar language to describe the sensuous effect of spectacles. Ménestrier had already stated, in his Traité des tournois (1669), that court spectacles have this “spiritual je ne sçay quoy mixed with their Magnificence” and create for the spectator an experience of the marvelous.Footnote 76 And as we have seen, his Des représentations en musique was directly inspired by the Longinian sublime in its conceptualization of the transporting, overwhelming, and elevating effects of musical spectacle.

At first sight, Ménestrier seems to be a marginal figure in relation to the classical doctrine with this defense of the irregular, the marvelous, and the spectacular. But soon enough his idea that the musical spectacle cannot be judged according to dramatic rules, but instead is much more a purely sensuous experience, became influential. La Bruyère, in his Caractères (1688), defends the enchanting and marvelous effect as the true essence of musical spectacle.Footnote 77 In the first half of the eighteenth century le merveilleux even became the poetical cornerstone of French opera. Gabriel Bonnot Mably writes in his Lettres à Madame la Marquise de Pompadour sur l'opéra (1741) that opera, through its effect of the marvelous, “must rob me of the use of my mind and my senses, so as to occupy me solely with my passions,” later adding, “I feel as though infused with the majesty of God.”Footnote 78 In his Lettres sur la danse ancienne et nouveaux (1751) Louis de Cahusac repeats many of Ménestrier's arguments, accentuating the enchanting, dazzling, and astonishing character of musical spectacles and the importance of the notion of le merveilleux:

Le merveilleux brought together in the theatre poetry, painting, music, dance, and technical skills with sufficient realism, and from the union of all these arts could come a ravishing whole, which took the spectators out of themselves and transported them to the enchanted worlds in the course of a lively performance.Footnote 79

Le merveilleux is clearly considered here as an aesthetic term. It designates music theatre as a spectacle of excess that pulls out all the stops to produce a maximum and almost ecstatic or sublime effect on the spectator. This is an effect that was already foregrounded in Ménestrier's writing on musical spectacles.

Conclusion

The writings of Michel De Pure and Claude-François Ménestrier show that in the seventeenth century there was already a rich discourse on the history, function, and impact of the performing arts. Both understood the performing arts in their broadest sense, as “spectacles.” The notion of the spectacle ranges here from theatrical representations, such as theatre, opera, and ballet, to cultural performances, such as carousels, tournaments, and royal entries. Due to this wide range, French seventeenth-century theories of the spectacle are not so much concerned with poetical questions that subordinate the spectacle to a fixed set of rules. Far more important are the questions of how spectacles function as multimedial phenomena and how they can evoke powerful emotions in the spectator, often resulting in a strong belief in the presence of what is actually performed. De Pure saw spectacles as vehicles for bringing back the dead or reviving distant times, and even considered them as the privileged media for the vivid presentation of abstract ideas. Ménestrier considered spectacles as images d'actions or as representations that have a strong agency upon the beholder in turning the representation into an experience of living presence.

To describe the strong effects spectacles could evoke, theorists referred to the increasing interest in the concept of the sublime. This renewed interest in the sublime—and in neighboring concepts such as magnificence, le merveilleux, or le-je-ne-sais-quoi—signaled a shift in the theoretical reflection and understanding of the arts. With its emphasis on the strong persuasive and emotional effect of the arts, the sublime and its seventeenth-century interpretations played a decisive role in the development of a more sensuous approach toward the arts, and can be seen as an important step toward the birth of aesthetics in the eighteenth century.

Within the early history of the sublime and of the emergent discourse of aesthetics, seventeenth-century theories of the spectacle have barely been studied, and spectacle itself has often been dismissed as a minor and superficial form of entertainment. However, the writings of De Pure and Ménestrier reveal to us an understanding of spectacle in the performing arts as far from superficial. By linking the overwhelming and transporting effect of spectacle to seventeenth-century concepts of the sublime, their writings are important in a two ways. First, they show us how by the second half of the seventeenth century the sublime acts as intermedial concept that is not restricted to the field of literature alone, but reaches other fields as well, including the performing arts. Second, their emphasis on the spectacular aspects of the performing arts and the strong sensuous experience they evoke in the spectator are extremely important for theatre and performance studies. These writings thus invite a reconsideration of the still widely accepted belief that it was not until the eighteenth century that the spectacular effects of performing arts became the object of theoretical reflection. In fact, the importance of the sublime for seventeenth-century theorists of the performing arts shows a more aesthetic approach to performance already in the making.