The 1957 motion picture Mother India, set in a rural village within newly independent India, follows the struggles of a poverty-stricken protagonist who had borrowed a loan of 500 rupees (about £40 then) from a local village moneylender. The moneylender, with the help of village elites, recovered the loan and additional interest by coercing the borrower to part with three-quarters of her harvested crop, leaving the protagonist in an unbreakable cycle of debt and poverty for the rest of the story.

Stories like these are common in popular depictions of the past. Credit exchange appears as an unequal struggle between the vulnerable borrower and the powerful lender. Money is essential to survival, and so are markets for credit. And yet, the credit market, perhaps more than any other, tends to be seen as a power game and a field of brutal exploitation.

Economic history and development economics attach a different meaning to credit. Credit was not just a source for survival but also a source for modernisation. Unfettered access to credit allowed people to tide over difficult times, consume enough when income dropped, and pay for this service when income returned to normal. Access also enabled individuals to start a business and existing business owners to grow and innovate. How do we reconcile both visions of credit – as an instrument of exploitation and as a symbol of distress against the view of credit as an instrument of economic development?

The book finds reconciliation between both visions through an analysis of rural credit markets in the Madras Presidency, a major province in colonial and early post-colonial India. It analyses historical sources documenting credit markets in the villages and districts of Madras over a period of four decades, investigating variations in the terms attached to credit, and the logic behind the application of these terms. This work tells us that lenders did lend but adjusted the terms to risks and the situation of the borrower. And that geography and enforcement problems shaped these risks and the economic situation of borrowers. In the end, these adjustments created many local variations in types of credit arrangements. Both harsh and lenient arrangements seem to co-exist.

Studying the logic behind lending arrangements explains why harsh terms exist and why lenient terms are not more pervasive. More specifically, the book asks: under what conditions do lenders give borrowers easy access to affordable loans? The history of credit markets in emerging market economies substantiates the importance of this question though is yet to provide a conclusive answer. Problems of selective access and high prices were common in credit markets across the Global South. Moneylenders, notaries and networks of family-run credit businesses commercialised capital markets and increased credit supply in Southeast Asia, Latin America and West Africa at different times in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Loans were often expensive and easier to access for merchants and traders than they were for peasants.Footnote 1 The rationale behind lending arrangements in historical settings – or explaining why loans were supplied in the way they were – remains an underdeveloped field in the comparative history of emerging markets. A similar gap exists in the history of credit markets in South Asia.

Explaining the prices attached to credit in India has fostered an ongoing dual debate, separately among groups of economists and groups of historians. One side of the debate focuses on power imbalance and inequity, indicating that prices were high because poor borrowers did not have enough power to bargain for lower prices and better conditions from the richer moneylenders.Footnote 2 Often ignored in this approach is that policymakers tried addressing power imbalance. Successive regulatory attempts, in the colonial and post-colonial periods, to diminish the market power of moneylenders did not improve the borrower’s position, suggesting that the underlying issue must lie outside of just power. Investigating the rationale behind the actions of lenders, the other side of the debate, the side that is currently filled with scholarship from economists, lays stress on risks and costs incurred by lenders to recover unpaid loans.Footnote 3 Since the 1970s, development economists have tested this approach in field experiments.Footnote 4 History of the lender’s account is overlooked, an omission relevant to readers interested in both Indian history and modern-day development in rural India as types of lending arrangements in colonial times seem to have persisted to the present. Scholars and policymakers have recently cast a spotlight on the harsh lending terms imposed by microfinance institutions, showing that credit still poses the same kind of anxieties as it did a hundred years ago.

The book contributes to a broader discussion on financial inclusion and, thus, speaks to a connected global audience. Providing sufficient credit to poor borrowers is not necessarily an emerging market problem but a central concern in development economics and economic history of the world. Indeed, it is one of those topics in which the two disciplines interact most closely. A reading of both disciplines tells us that the poor had easier access to credit in some regions than others, even though the types of lenders were similar across regions. Banks were not always the major suppliers of credit and even when they were, they seldom catered to borrowers from all income groups and economic sectors. Notaries, intermediaries and cooperatives provided reasonably priced loans to large segments of the market before and alongside the spread of banks in Western Europe.Footnote 5 Indeed, credit from cooperatives facilitated transformative growth processes in parts of Europe as recently as the early twentieth century.Footnote 6 The book visits a part of the world where moneylenders and cooperatives did not supply enough affordable credit to stimulate growth. It finds that a tripartite set of risks, a set that includes region-specific ecology, the design and persistence of colonial institutions, and ineffectual market regulation, stifled lending, especially lending to the poor.

The book, in other words, designs a blueprint to investigate the (under) development of financial markets. In doing so, it contributes to institutional economic history, which foregrounds institutions like law, but has not paid sufficient attention to interactions between credit, debt law and informal arrangements. Familiar institutional typologies divides systems into ‘formal’ and ‘informal’.Footnote 7 Typically, the distinction lies in regulation and scope of the rule of law. Economists and economic historians see independent courts and contract laws (the formal rules) as regulators of banks (the formal players).Footnote 8 Moneylenders are seen in a separate sphere as informal players in markets regulated by social norms.Footnote 9 Recent works on credit in colonial India have started to challenge these typologies, showing that moneylenders used mortgage contracts, and debt laws affected the supply of these mortgage loans in the nineteenth century.Footnote 10 The book shows greater dynamism in the co-existence and flexibility of institutional forms. Moneylenders were indeed affected by laws. They also vacillated between court-enforced and socially enforced contract types, blurring the boundaries between ‘formal’ and ‘informal’ systems. Lessons from this work, therefore, intersect institutional change and policy, showing how the design of laws and types of contract enforcement affected the affordability and inclusivity of non-banking credit.

Colonialism, Credit and Development in South India

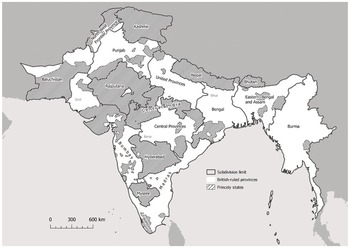

The study of agricultural markets is central to understanding economic development in colonial India. Two-thirds of the Indian population relied on cultivation to make a living in 1900, a figure that did not change much until the latter decades of the twentieth century.Footnote 11 Colonial India, as drawn in Figure 1.1, spanned an enormous territory, with long coastlines in the east and west, as well as mountain ranges in the north and south.Footnote 12 Rivers emanating from the mountains run through fertile valleys in the north and, albeit to a smaller extent, in the south. The vast majority of India’s population cultivated on four landforms: coastal plains, dry hinterland, fertile valleys and terraced hills. Colonial Madras was no different. Madras spanned from the southern tip to the Deccan Plateau, which bridged south and central India. Laterally, the province ran from the western to the eastern coastline. Hill ranges ran across central areas in the north and south of the province. Three main rivers flowed from the west to the east, with its main tributaries also culminating downstream in the eastern deltas. The Madras province, geographically speaking, was a microcosm of the Indian sub-continent while its size, covering 48,500 square miles and housing 29 million people in 1950, justifies studies of the region as its own entity.Footnote 13 Agriculture employed millions but yielded low and unequal output in Madras, as it did with the rest of British-ruled India.

Figure 1.1 Provincial boundaries in colonial India, 1909.

Notes: Figure modelled on the map in the Imperial Gazetteer of India Atlas (Oxford, 1909), 20.

Growth and productivity stagnated in the agricultural sector throughout the colonial period and until 1960, in one account, the year when the Green Revolution began.Footnote 14 Agrarian India did experience growth in trade during the nineteenth century. Transport infrastructure improved, markets developed and cultivators shifted from payments in kind to transactions in cash.Footnote 15 Households transitioned from subsistence to cultivation for profit as cash crop acreage saw a steady increase. Despite a process of commercialisation and expansion in commodities traded, real incomes grew modestly and innovation was limited as production processes remained trapped in a low-yield regime. Output was volatile, with some years of mass famine.Footnote 16

Credit supply offered little scope for investment-led growth in colonial and early post-colonial India. Commercial banks did not lend in the agricultural sector before 1960. Private moneylenders and cooperatives were the major suppliers of credit, the former being more predominant during the period. Missing commercial banks did not mean that credit suppliers were scarce. In Madras, moneylenders were present in every village, and each lender commonly provided loans to multiple borrowers. However, access to loans was selective, value of loans was small and prices of loans were often exorbitant. These conditions did not allow the majority of South Indians to invest in new production processes and often failed to provide needy borrowers maintenance in times of famine.

Two types of moneylenders provided credit in rural India. Indigenous bankers and traders from the cities provided credit to some cotton and wheat farmers in select districts within Bombay and Punjab.Footnote 17 In Madras, and across the majority of rural districts in colonial India, farmers with disposable income provided loans to other farmers. Lenders who were also farmers faced two concurrent challenges in bad years. When crops failed, they incurred losses in farming business from decline in quantity, and thus value, of produce, and incurred losses in credit business because borrowers could not meet their credit bills.

The colonial period was a turbulent time for commodity and credit markets in South India. Crop output was volatile, and development was continually interrupted by periods of negative output growth.Footnote 18 Debt defaults, as a result, were common and impossible to predict. Lenders found the precarity in earnings and defaults especially difficult to handle in the inter-war period. Commodity prices crashed during the Great Depression, ballooning the value of unpaid credit bills. Defaults compounded, fresh loans dried up and moneylenders were reluctant to renew old debts. This attracted the attention of policymakers. Soaring interest rates and high default rates in the context of stagnating living standards and rising inequality worried colonial officials and Indian nationalists.Footnote 19

Colonial administrators and nationalists saw credit exchange as an exploitative arrangement. The government acted on a belief that investment remained low and peasants remained poor because market forces allowed moneylenders to extract rents from borrowers. Colonial officials feared peasant uprisings as a result of inequity and power imbalance. Adopting a different tone, nationalists argued that elite-favouring policies in the colonial regime affected the livelihoods of peasants. Key actors accused the colonial government of promoting regressive taxation laws and failing to regulate the power of rich moneylenders. The concerns, though motivated by different factors, encouraged the same policy response. Cutting across colonial and nationalist lines, policymakers promoted the protection of borrowers either as a method of preventing riots in the countryside or as a solution to inequality.

Provincial governments were responsible for regulating rural credit markets. As such, the provinces executed different policy responses at different times from the late nineteenth century. The Bombay Deccan was the first to regulate rural credit markets in 1879. The government in Punjab followed suit in 1900. Both governments regulated mortgage lending to limit the transfers of land from cultivators to urban moneylenders. Urban moneylenders scarcely lent in rural Madras so provincial policymakers did not believe that land alienation needed regulating.Footnote 20 Credit regulation in Madras, therefore, came later.

The government in Madras implemented a two-pronged approach to controlling the market power of moneylenders: one directly curtailing market power by regulating the prices charged by moneylenders and the other an indirect attempt to diminish market power by increasing competition in the market. On the direct approach, provincial officials enforced a price ceiling on loans from moneylenders in 1937. Moneylenders were legally bound to charge borrowers a fixed rate of interest that was significantly lower than the market average. On the indirect approach, the colonial government designed credit cooperatives to compete with moneylenders. The government introduced the first state-regulated cooperative in the Madras Presidency in 1904. The number of cooperatives saw a steady increase in the 1920s with particularly large, government-financed capital injections into the sector in the 1940s and 1950s. The government in early post-colonial Madras persevered with, and even strengthened, colonial-era interventions.

The timing of intervention is central to the book’s structure. The book proceeds in two sections: one analysing the factors that explain lending patterns in the unregulated market and the other showing the impact of interventions on the supply of credit.

The first section analyses the ecological and institutional barriers to lending money and the ways these barriers affected lending patterns in the unregulated market.Footnote 21 Farming was mostly rainfed and dependent on volatile rainfall patterns. Chances of crop failure were high, resulting in dual risks for borrowers and lenders. Poor borrowers that relied on seasonal income ran the risk of defaulting on loans and losing access to credit in subsequent years. Creditors risked losing earnings from capital, returning to more modest means than before. Climatic risk, in turn, affected enforcement structures in a regionally specific pattern. The design of contract laws was unsuited to recover loans from borrowers that did not wilfully default on loans, making courts an inefficient and expensive forum for dispute resolution. The book for the first time shows that lenders in rural India adapted pricing and enforcement strategies to risks and transaction costs. They allocated credit selectively in dry zones and more inclusively in irrigated regions. They relied on courts to recover loans when cost-efficient to do so otherwise resorting to informal contracts, compensating for the costs of enforcing contracts in the prices of loans.

The second section evaluates the design and consequences of credit intervention, showing that regulation was part of the problem of market failure. A political ideology prioritising equity over efficiency inspired the design of credit intervention in the colonial and early post-colonial period.Footnote 22 The book finds that tailoring the market to be fairer to the borrower was a superficial response to the underlying problem. After the government enforced the interest rate ceiling, moneylenders were no longer able to price loans adjusting for the risks of lending. Creditors either stopped lending entirely or evaded the law. Credit supply contracted for the poor and remaining creditors went underground, supplying loans outside formal procedure and pricing loans as high or higher than prices in the unregulated market. Attempts to make the market more competitive did not solve the problem either. Prevailing political objectives led to a cooperative banking structure operating with low savings and weak regulation. The regulatory problem ultimately led to exclusion of poorer peasants from accessing credit and over-leveraged cooperative banks. Regulations to make the market more equitable, paradoxically, left borrowers more vulnerable to credit exclusion and high prices.Footnote 23

The book has an enduring message, carrying lessons for credit and development in modern-day India.Footnote 24 The agricultural sector in South India continues to be fraught with challenges. Poverty levels are high and persistent, inequality levels are rising, and at the centre of these issues are the lack of credit access and harsh conditions attached to credit for low-income borrowers. The institutional setup and market structure changed after 1960. Credit suppliers multiplied with the entry of commercial banks and microfinance institutions in the agricultural sector. Problems of high default rates, selective access and high prices, however, did not disappear. Governments reacted in a similar pattern, acting on a belief that credit markets remained underdeveloped because they were informal and exploitative. Capital Shortage explains how this ideology was founded on a misdiagnosed problem. Risks and ineffective regulations persisted, continually constraining credit supply and restricting investment potential for the rural poor.

Sources

Studying rural credit markets comes with challenges because historical data is scarce. Markets operated within villages, yet contemporary commentators on credit tended to provide broad claims with aggregated data at the provincial level. Government reports and court judgements in colonial India, however, offer novel insights. Policymakers sought to inform policy interventions by compiling data at the district and occasionally village level in official surveys. The number of credit reports compiled by the Madras government increased from the 1920s. That moneylenders often used contracts and approached courts leaves a trail of legal sources that are a valuable addition to official reports.

The book analyses two categories of government reports on credit: annual reports and isolated reports. In the annual category, yearly reports by the government departments responsible for recording land registrations and administration of cooperatives provide data and qualitative information on lending patterns in rural districts. In the isolated category, the first section of the book analyses village-level credit surveys from 1930 and 1935. The Banking Enquiry Committee, under the government’s supervision, hired a team of investigators to survey credit in eighty villages during the late 1920s.Footnote 25 The Report on Agricultural Indebtedness, published in 1935, expands on the data provided by the Banking Enquiry Committee.Footnote 26 The report, through a larger number of investigators, surveyed 141 villages showing data on types of moneylenders, credit instruments used and purposes of borrowing. The second section of the book analyses a series of government-commissioned surveys in the 1940s and 1950s. Two of these surveys, in particular, offer village- and district-level data. One, published in 1946, estimated if credit laws in the late 1930s changed borrowing patterns in select regions. Another, commissioned by the Reserve Bank of India in 1951, surveyed villages across rural India between 1951 and 1954. The book situates data from government surveys against material from other micro-regional reports, including District Gazetteers and one-off official publications on climate and the agricultural sector.

Court records offer a novel set of sources that have yet to be fully studied in credit-related literature. Case files containing counsels’ pleadings are inaccessible to the public. Apart from the laws themselves, the case records that are accessible contain summaries of pleadings and the court’s final judgement. The book analyses case records from the Madras High Court.Footnote 27 The third and fourth chapters examine select case judgements that consider the enforceability of credit contracts as well as the legality and impact of credit policies from the late 1930s and early 1940s.

Finally, the book supplements government reports and court records with material from contemporary studies, written by economists and policymakers directly involved in the committees that compiled government-commissioned surveys on rural credit in the 1930s and 1940s.Footnote 28 These articles and books provide further insights into the government’s approach to rural credit.

The book now turns to the first substantive chapter, providing an overview of agriculture, commerce and governance in South India before and during colonial rule.