Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by the depletion of dopaminergic neurons in basal ganglia, precisely in substantia nigra pars compacta, resulting in motor symptoms such as bradykinesia, rigidity, and tremor.Reference Parent and Parent 1 Recent evidence has highlighted the importance of non-motor symptoms, with depression, anxiety, and apathy being the most studied. Excitement, increased energy, mood elevation, disinhibition, hypomania, and mania have been poorly explored in PD. Increased rate of (hypo)manic symptoms has been reported in patients who underwent deep brain stimulation surgery.Reference Ulla, Thobois and Lemaire 2 , Reference Doshi 3 Other studies reporting excitatory symptoms in PD are focused on antiparkinson-drug-induced mania or hypomania, with prevalence rates ranging between 10%Reference Voon, Saint-Cyr and Lozano 4 and 16.7%.Reference Maier, Merkl and Ellereit 5

In the perspective of a personalized approach to mental disorders, especially in bipolar disorder (BD),Reference Perugi, De Rossi and Fagiolini 6 recent evidence supports the existence of a distinction between early-onset neurodevelopmental vs late-onset neurodegenerative bipolarity.Reference Buoli, Serati and Caldiroli 7 Late-onset BD can be elicited by many neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer disease, frontotemporal dementia, vascular dementia, silent cerebral infarcts and stroke, normal pressure hydrocephalus, brain injury, brain tumors, epilepsy, infections of the central nervous system, Huntington disease, and prion diseases. 8-11 The presence of BD has been studied in different neurodegenerative diseases such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Huntington diseaseReference Zarowitz, O’Shea and Nance 12 , Reference Bertram and Tanzi 13 and evidence linking BD to the onset of dementia has been reported.Reference da Silva, Gonçalves-Pereira, Xavier and Mukaetova-Ladinska 14 Some structural brain changes, such as hippocampal atrophy and fronto-striatal abnormalities, together with increased levels of amyloid plaques, pro-inflammatory changes and alterations in nerve growth factors are likely to underlie both mood disorders and dementia, giving strength to the hypothesis of a close link between psychiatric pathology and cognitive dysfunction.Reference Byers and Yaffe 15 In this vein, a recent study showed clinical and molecular similarities between BD and Alzheimer disease hypothesizing a possible connectionReference Corrêa-Velloso, Gonçalves, Naaldijk and Oliveira-Giacomelli 16 and a meta-analysis found a positive association between BD and the risk of developing dementia.Reference Postuma, Berg and Stern 17 Interestingly, some authors proposed to label clinical variants of bipolarity characterized by late onset and elicited by neurodegenerative processes as BD type VI.Reference Ng, Camacho and Lara 8

Among neurodegenerative diseases, PD shares several neurobiological and clinical features with BD and a putative association between the two conditions has been repeatedly suggested. 18–20 The risk of developing PD has been found to be specifically increased in major depression,Reference Nilsson, Kessing and Bolwig 21 while discordant evidences have been reported for BD. Kummer et al found a prevalence of BD type I and II in PD comparable to that of the general populationReference Kummer, Dias, Cardoso and Teixeira 22 and a lower number of patients with PD was found in a BD veteran cohort compared with controls.Reference Kilbourne, Cornelius and Han 23 Conversely, a positive association between the two conditions have been repeatedly described by other authors. 24–26 According to a recent systematic review and meta-analysis having a diagnosis of BD highly increase the likelihood of a subsequent diagnosis of PD.Reference Faustino, Duarte and Chendo 27 Accordingly, the authors highlighted the importance of accurately differentiate between the idiopathic and the drug-induced form of the disease in BD patients with parkinsonism features. Since standard treatments for BD, including antipsychotic and mood stabilizers, are associate with an increased risk of parkinsonism, clinicians are more prone to infer a drug-induced parkinsonism rather than an idiopathic PD in patients with BDs.Reference Faustino, Duarte and Chendo 27 In addition, a longitudinal study on 56 340 BD patients showed that higher rates of psychiatric admissions for both manic/mixed and depressive episodes were significantly associated with an increased risk of developing PD.Reference Huang, Cheng and Huang 28

The present study is aimed to explore the possible relationship between Bipolar Spectrum disorders and PD, by systematically evaluating the rate of comorbidity and its possible clinical implications.

Methods

This is an exploratory observational, cross-sectional, and cohort study. The sample consisted of 100 patients, consecutively recruited at the Movement Disorders Section of the Neurological Outpatient Clinic of the University of Pisa according to a naturalistic consecutive approach, who received the diagnosis of probable PD. Clinical diagnosis was done according to the Movement Disorder Society Criteria.Reference Postuma, Berg and Stern 29 Whenever disease onset dated back to before 2015, patients were first diagnosed according to the UK Parkinson’s Disease Brain Bank criteriaReference Gelb, Oliver and Gilman 30 and the diagnosis was subsequently confirmed according to current criteria.Reference Postuma, Berg and Stern 29 All patients included had underwent a (123)I-Ioflupane SPECT and showed signs of nigrostriatal degeneration. Patients showing atypical parkinsonian signs were excluded. Clinical evaluations were performed by neurologists with expertise in movement disorders from October 2017 to March 2018. All patients in treatment were evaluated in the defined ON state, when their antiparkinson medications was working. All participants signed a free and informed consent previously approved by the institution’s Ethics Committee before being included in the study. The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Assessment procedures

Neurological clinical data (eg, frequency of motor fluctuations and involuntary movements) were retrieved from medical records and rating scales routinely carried out by neurologists at follow-up visits performed at most within 1 month before the psychiatric evaluation. When available, the subitem III of the Unified PD rating scale Data Form (UPDRS)Reference Fahn, Elton, Fahn, Marsden, Calne and Goldstein 31 score was adopted as a measure of motor signs severity. The Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) was used to screen for cognitive impairment.Reference Folstein, Folstein and McHugh 32 Early-onset PD was defined, in accordance with previous studies, 33–35 as the onset of PD before the age of 50 years.

All patients were extensively evaluated by psychiatrists with at least 2 years of experience with neurodegenerative disorders Silvia Bacciardi (SB), Camilla Elefante (CE). Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI)-Plus version 5.0.0,Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier and Sheehan 36 a structured interview for the diagnosis of the principal mental disorders according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-IV-TR criteria, 37 was administered to assess lifetime psychiatric comorbidity. Affective disorders and first degree family history of mood disorders were assessed with the Semi-structured Interview for Mood Disorders (SIMD-R),Reference Cassano, Akiskal and Musetti 38 a widely used instrument for the diagnosis and clinical characterization of mood disorders in BD patients.Reference Perugi, Quaranta and Belletti 39 impulse control disorders (ICDs) such as gambling, compulsive sexual behavior, compulsive buying, have been assessed according to the DSM-IV-TR classification, which recognizes pathological gambling as a specific disorder, while compulsive sexual behavior and compulsive buying are classified as ICDs not otherwise specified. 37 In addition, accordingly with DSM-IV-TR proposed research criteria 37 and Weintraub and Claassen,Reference Weintraub and Claassen 40 we included binge eating disorder among ICDs.

Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) Expanded Version 4.0 was used for the evaluation of symptomatic domains related to affective, anxious, and psychotic disorders. The scale consists of 24 items, which investigate relatively independent psychopathological dimensions, accounting for both the severity of the symptoms, the frequency with which they occur and the functional impairment (from 1 = absent to 7 = very severe).Reference Roncone, Ventura and Impallomeni 41 The affective temperamental characteristics were assessed by means of the Temperament Evaluation of Memphis, Pisa, Paris and San Diego-Münster, a self-evaluation form consisting in 35 items coded on a 5-point Likert scale (from absent to very much).Reference Erfurth, Gerlach and Hellweg 42 For each subject, dominant temperament was determined as the highest score obtained among all five temperamental subscales scores after standardizing (ie, expressed as z-score). Non-motor symptoms in PD were assessed by Non-Motor Symptoms Scale (NMSS).Reference Chaudhuri, Martinez-Martin and Schapira 43 The scale focuses on the month before the interview and consists of 30 items divided into nine domains: cardiovascular, sleep/fatigue, mood/cognition, perceptual disorders/hallucinations, attention/memory, gastrointestinal symptoms, urinary symptoms, sexual function, and miscellaneous. The score for each item is based on a combination of severity (from 0 to 3) and frequency (from 1 to 4). The total score goes from 0 to 360. Antiparkinson drug-induced psychiatric complications have been assessed with the Scales for Outcomes in Parkinson’s Disease-Psychiatric Complications (SCOPA-PC), a seven items scale exploring hallucinations, illusions, paranoid ideation, altered sleep patterns, confusion, sexual concerns, and compulsive behaviors. Each item can be given a score from 0 (no symptoms) to 3 (severe symptoms). The total score ranges from 0 to 21 and a higher score reflects more severe psychiatric complications.Reference Visser, Verbaan and van Rooden 44 Apathy has been investigated with Lille Apathy Rating Scale (LARS), a structured interview rating patient’s symptoms in the previous four weeks.Reference Sockeel, Dujardin and Devos 45

Statistical analyses

Demographic and clinical characteristics were analyzed by means of descriptive analyses. In order to explore the possible relationships between PD and BD, patients were divided into three groups on the basis of lifetime psychiatric comorbidity, respectively with Bipolar Spectrum disorders (BD type I, BD type II, spontaneous, or drug-induced hypomania), with and without other psychiatric comorbidities. Comparative analyses among the different subgroups were conducted using chi-square test for categorical variables (with z-test contrasts and Bonferroni’s correction), and one-way analysis of variance for continuous variables (with a posteriori contrasts according to the Scheffé’s procedure). Finally, a logistic regression model was applied to rule out the role of antipsychotic use in anticipating PD onset in bipolar patients. Accordingly, Bipolar Spectrum comorbidity and lifetime antipsychotic use were included in the model as independent variables and early-onset PD as the dependent variable. The significance level in all statistical tests was set to 0.05. All analyses were performed using SPSS 20.0.

Results

Sample characteristics

The sample consisted of 61 males and 39 females, with a mean age of 67.2 years (SD = 10.6; range 37–90). Marital status was available in 90 patients: 75 were currently married, four had never been married, two were separated/divorced, and nine were widow. Education and employment status were available for all subjects. Fifteen patients were graduate, 29 had a high school diploma, and the others had a lower level of education. Sixty subjects were retired, eight were unemployed, and the remaining ones were currently employed.

The average age at PD onset was 59.2 ± 12.0 with a minimum of 19 and a maximum of 82 years and 21 patients belonged to the early onset group (≤50 years). Sixty-one percent of patients were taking at least a psychiatric medication at the moment of the interview and 96% were assuming an antiparkinson therapy. First-degree family history for mood disorders was present in 36 patients. Lifetime psychiatric comorbidity was observed in 71 patients; the onset of the psychiatric symptoms preceded PD motor symptomatology in 56% of cases. Lifetime unipolar depression was diagnosed in 26 subjects, while Bipolar Spectrum disorders were observed in 32 cases: eight subjects were diagnosed as Bipolar I, nine as Bipolar II, seven reported episodes of spontaneous hypomania without a history of major depression, and eight had positive history of drug-induced hypomania (Figure 1). Twenty-two patients (68.8%) from the Bipolar Spectrum comorbidity group were males. Bipolar patients were, on average, 61.1 ± 11.1 years old (range 37–90). Other lifetime psychiatric comorbidity was observed in 39 subjects (23, 59.0% males, mean age 70.9 ± 7.8 years, range 48–89). Mood and anxiety comorbidities were the most frequently represented in this group, with 18 patients diagnosed with both anxiety disorders and major depressive disorder, 10 with only anxiety disorders, and eight with only major depressive disorder. Finally, 29 patients were negative for lifetime comorbid psychiatric disorders (16, 55.2% males; mean age 68.6 ± 10.6 years, range 40–84).

Figure 1. Prevalence of lifetime mood disorders in a sample of 100 PD patients.

Group comparisons

No differences in gender distribution were observed between the groups, while patients with Bipolar Spectrum comorbidity at the evaluation were significantly younger than the others. The age of onset of PD in Bipolar Spectrum patients was significantly lower than in the other groups and, accordingly, an early onset of PD was significantly more frequent in the Bipolar Spectrum group compared with patients showing other psychiatric comorbidities. Motor fluctuations were significantly more frequent in patients with both Bipolar Spectrum and other psychiatric comorbidities and involuntary movements prevalence was significantly higher in the Bipolar Spectrum group than in those without psychiatric comorbidities. No differences among groups have been found regarding illness duration, PD therapy duration, lateralization of signs, current use of L-Dopa and dopamine agonists, lifetime use of dopamine agonists, treatment length, and maximum prescribed dosage. No significant differences between the Bipolar Spectrum groups and the other groups were observed in UPDRS subitem III and NMSS total and domain scores, except than in the sexual function domain, in which bipolar patients showed significantly less impairment than subjects with other psychiatric comorbidity (Table 1).

Table 1. PD Features in 100 in Treatment Patients.

Abbreviations: LT, lifetime; NMSS, Non-Motor Symptoms Scale; PD, Parkinson’s disease; UPDRS, Unified PD Rating Scale.

Z-contrasts: †Group A > Group B; ‡Group A, Group B > Group C; §Group A > Group C.

Scheffe F-test: aGroup B, Group C > Group A; bGroup B > Group C; cGroup B > Group A.

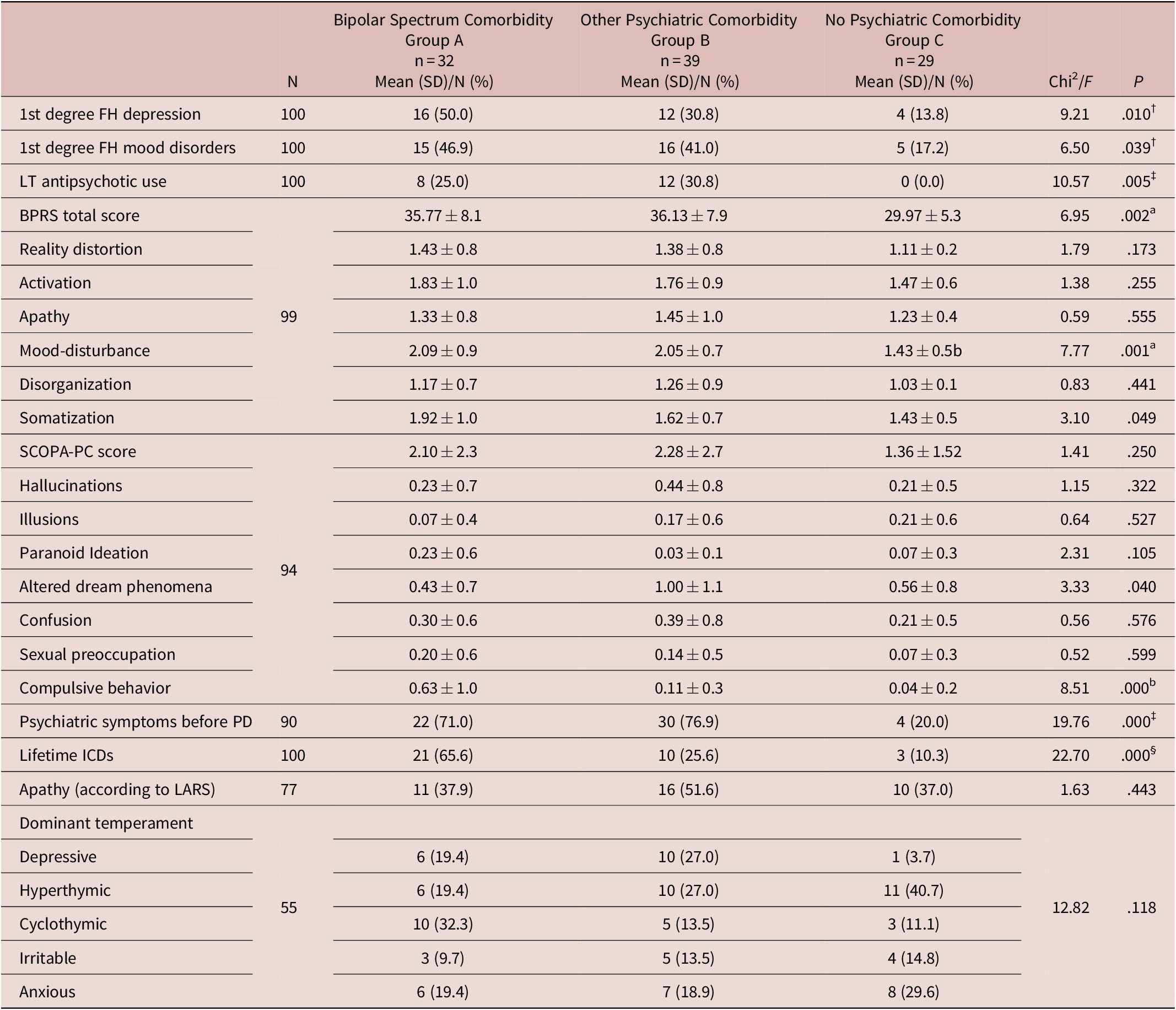

As for psychiatric variables, first-degree familiarity for depression and mood disorders were significantly higher in Bipolar Spectrum patients compared with subjects without psychiatric comorbidities. In addition, both the groups with psychiatric comorbidities (ie, bipolar or not) showed higher rates of psychiatric symptoms before PD onset and higher BPRS total and mood-disturbance subscale scores, compared with the group without comorbidity. Conversely, lifetime prevalence of ICDs and compulsive behavior subscale from SCOPA-PC were significantly higher in the Bipolar Spectrum group compared with both the other groups. Finally, bipolar patients and patients with other psychiatric comorbidity showed comparable rates of lifetime antipsychotic use, which were significantly higher than in patients without any psychiatric comorbidity (Table 2).

Table 2. Psychiatric and Cognitive Characterization in 100 PD Patients.

Abbreviations: BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; FH, family history; ICDs, impulse control disorders; LARS, Lille Apathy Rating Scale; MMSE, Mini Mental State Examination; PD, Parkinson’s disease; SCOPA-PC, scales for outcomes in Parkinson’s disease-psychiatric complications.

Z-contrasts: †Group A > Group C; ‡Group A, Group B > Group C; §Group A > Group B, Group C.

Scheffe F-test: aGroup A, Group B > Group C; bGroup A > Group B, Group C.

To rule out a possible confounding effect of lifetime antipsychotic exposure on the association observed between Bipolar Spectrum comorbidity and early-onset PD (≤50 years), a logistic regression was performed. As expected based on previous results, a significant effect of lifetime antipsychotic use in predicting early-onset PD was excluded (B = 0.867, OR = 2.38, 95% CI = 0.75–7.59, P = .143), while the association between the latter and Bipolar Spectrum comorbidity was confirmed (B = 1.608, OR = 4.99, 95% CI = 1.78–14.05, P = .002) by the multivariate logistic regression model.

Discussion

As expected, the prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities was high in our sample. Indeed, 71% of patients were affected by at least one psychiatric life disorder according to MINI-plus and 61% were taking a psychopharmacological treatment. These findings are in line with previous longitudinal studies, reporting a cumulative prevalence of psychiatric disorders in PD over 50%.Reference Weintraub and Burn 46 Bipolar Spectrum disorders were observed in approximately one third of cases with a prevalence of BD type I, II and lifetime spontaneous and drug-induced hypomania respectively of 8%, 9%, 7%, and 8%. BD in PD is poorly investigated, with paucity of data in literature. To the best of our knowledge only one study reported the prevalence of BD subtypes in PD patients, with rates ranging from 1% for BD I to 5% for BD II.Reference Nilsson, Kessing and Bolwig 21 This low frequency is in line with the percentage reported for the general population and it seems unlikely in a population where neuropsychiatric disorders are highly represented. However, higher scores in mania rating scales have been reported in PD patients in comparison with healthy controls.Reference Maier, Merkl and Ellereit 5 Some more information could be indirectly drawn from studies on depression, treatment-induced hypomania or mania and ICDs. According to the existing literature, depressive disorders in PD range from 40% to 50% of the cases, with approximately one half identified as unipolar major depression, while the rest as BD, minor depression, dysthymia, and sub-syndromal depression.Reference Reijnders, Ehrt and Weber 47 The low prevalence rate of BD previously reportedReference Nilsson, Kessing and Bolwig 21 seems to be in contrast with the high prevalence of lifetime drug-induced hypomania or mania in PD, ranging between 10%Reference Voon, Saint-Cyr and Lozano 4 and 16.7%,Reference Maier, Merkl and Ellereit 5 which suggests a high risk for bipolarity. In addition, some authors hypothesized ICDs to belong to the Bipolar Spectrum, based on overlapping risk factors, such as novelty seeking and trait impulsivity, and clinical manifestationsReference Weintraub and Claassen 40 , 48–50. Taking all together, these findings suggest that Bipolar Spectrum in PD patients is probably underestimated, possibly due to the lack of proper psychiatric screening tools, difficulties to collect anamnestic history of hypomanic symptoms and overestimation of major depressive disorders based on accounts of depressive symptoms.

Interestingly, impulsive–compulsive disorders have been previously associated with an earlier onset of PD and with a higher rate of depressive symptoms in a sample of 490 Danish PD patients.Reference Callesen, Weintraub, Damholdt and Møller 51 In accordance with the hypothesis of a common diathesis for both Bipolar Spectrum disorders and ICDs, our results suggested an association between Bipolar Spectrum disorders and both ICDs and early-onset PD. Similarly, involuntary movements have been repeatedly associated both with early-onset PD and BD comorbidity.Reference Maier, Merkl and Ellereit 5 , Reference Kummer, Dias, Cardoso and Teixeira 22 , Reference Callesen, Weintraub, Damholdt and Møller 51 Consistently, in our sample, while motor fluctuations were more frequent in both groups characterized by psychiatric comorbidity, involuntary movements were specifically more represented in the bipolar group. Whether this could be mainly due to differences in PD age of onset, rather than bipolar comorbidity, needs further exploration.

Importantly, the onset of PD in our bipolar patients preceded by approximately 10 years that of non-bipolar patients, with approximately two patients out of five with Bipolar Spectrum disorders showing an early onset (≤50 years). Most Bipolar Spectrum patients showed psychiatric symptoms before the onset of PD and, since a higher risk of PD has been recently reported in bipolar patients,Reference Huang, Cheng and Huang 28 the relationship between BD and PD seems to be bidirectional. We could hypothesize that patients with a history of hypomania, mania, or mixed features could show a higher vulnerability for neurodegenerative processes and, if prone to PD, they could develop the disease at lower ages. Alternatively, a subtype of PD, characterized by an earlier onset, could be more prone to develop hypomanic symptoms and ICDs, even before the onset of PD, and subsequently treatment complications. In our sample only eight (8.0%) patients showed a history of treatment-induced hypomania or mania only, while the remaining 24 (24.0%) reported lifetime spontaneous episodes, supporting the hypothesis that hypomania and mania in early-onset PD are not only determined by the greater exposure to antidopaminergic drugs. In particular, no statistically significant differences were found among Bipolar Spectrum patients and both PD patients with other psychiatric comorbidities or without comorbidities in terms of PD therapy duration, current use of dopamine agonist and L-Dopa, dopamine agonist treatment duration and maximum dosage. Thus, among our patients, dopaminergic treatments do not seem to be the main contributor to the development of excitatory symptoms. Interestingly, a role for the exposure to antipsychotics in anticipating PD onset could also be partially ruled out, based on comparable lifetime antipsychotics use rates in bipolar patients and patients showing other psychiatric comorbidities, which, however, did not show a lower age at PD onset compared with subjects without any comorbidity.

No differences in gender distribution were observed between the groups and a slight preponderance of males was observed, independently from psychiatric comorbidity and in accordance with previous results.Reference Georgiev, Hamberg, Hariz, Forsgren and Hariz 52

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, the clinical setting (a tertiary neurological unit) may have not been representative of the whole PD population, but of a more complicated subpopulation. Second, the assessment of psychopathology and drug treatment was mostly retrospective and consequently at risk of recall bias. This is especially relevant in the field of BD, since manic and hypomanic episodes are, by definition, characterized by lack of awareness and could go unnoticed in retrospective evaluations. However, instruments specifically designed for mood disorders, such as the SIMD-R used in our study, could significantly assist in the assessment of BD. The retrospective evaluation of symptoms and signs is particularly relevant for hypomanic episodes, whose duration is usually lower than that of major depressive episodes, and consequently underestimated in cross-sectional evaluations, which are more likely to highlight depressive and anxious symptoms.

Conclusion

Bipolar Spectrum disorders have been shown to occur in almost a third of PD patients visited in a specialized unit for movement disorders. These patients showed an earlier onset of PD, more frequently involuntary movements and lifetime ICDs. This latter association makes BD screening recommended for the management of ICDs in PD. More speculatively, the co-occurrence of a bipolar diathesis, ICDs and motor complications in early-onset PD may be indicative of a specific subtype of PD whose pathophysiology and course of illness deserves further investigation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Luca Larini for contributing to the collection of medical records and assisting visits.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Disclosures

Giulio Perugi, Silvia Bacciardi, Camilla Elefante, Giulio Emilio Brancati, Sonia Mazzucchi, Eleonora Del Prete, Daniela Frosini, Icro; Maremmani, Lorenzo Lattanzi, Roberto Ceravolo, and Ubaldo Bonuccelli declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.