I. Introduction

The constitutional rules that govern how states engage with international law have profound implications for foreign affairs. For instance, few countries require subnational entities like states or provinces to approve treaties. Yet, because Belgium's constitution does, a veto by its Walloon region nearly blocked the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) between Canada and the European Union.Footnote 1 In many countries, the national executive enjoys broad unilateral power to withdraw from treaties. But recently, the South African Constitutional Court held that the government could not constitutionally withdraw from the International Criminal Court without parliamentary approval.Footnote 2 While some national courts defer to the executive in matters of foreign relations, others have become more interventionist. The German Federal Constitutional Court recently blocked Germany's participation in a crucial European monetary program unless the government showed that the program was consistent with the German Constitution.Footnote 3

These and other constitutional arrangements for making and enforcing international law are at the heart of foreign relations law, “the domestic law of each nation that governs how that nation interacts with the rest of the world.”Footnote 4 They involve a host of design choices that shape a state's ability to engage in international legal transactions and to effectuate them domestically. Should the executive be able to conclude treaties on its own, or should it require legislative approval? If so, should a supermajority be required? Should the same rules apply to withdrawing from existing treaties? Once treaties are concluded, can they be applied directly by courts as part of domestic law? What happens when a treaty conflicts with a statute or another source of domestic law, such as state or provincial legislation? States face similar choices in deciding whether and how to give effect to customary international law (CIL) in their legal system.Footnote 5

In a world of global interdependence where vital areas of policy—security, trade, the environment—require international coordination, these rules reflect fundamental choices states make to balance global governance and sovereignty. Yet, we currently lack comprehensive research on these rules’ global patterns and how they evolved.Footnote 6 As a result, we lack understanding of basic questions such as whether foreign relations laws reflect countries’ unique constitutional traditions or are standardized; whether countries approach foreign relations law choices strategically to improve their international position; and whether these choices reflect domestic political preferences and goals, such as committing to democratic government or human rights.

In this Article, we use an original global dataset to attempt to answer these questions systematically. This dataset captures three important areas of foreign relations law—treaty-making procedures, the status of treaties in domestic law, and national courts’ application of CIL—for 108 countries over the period 1815–2013. The data, gathered over multiple years with the participation of dozens of researchers, incorporates information from foreign constitutions, legislation, judicial decisions, and secondary sources to reconstruct these doctrines and how they have evolved. Our data include both quantitative and qualitative information.Footnote 7 The dataset consists principally of some four dozen variables that capture states’ foreign relations law choices over time. In addition, our data-collection process generated extensive qualitative and historical information that allow us to trace the evolution of foreign relations law over time.

We use these data to provide a comprehensive picture of over a century of foreign relations law around the world. We do so, first, by exploring our quantitative data using a statistical data-dimensionality reduction method that allows us to map foreign relations law in two-dimensional space. Using this method, we systematically analyze and map countries’ foreign relations law choices, compare them, and track the historical trajectory of foreign relations law globally. We supplement this quantitative analysis with historical qualitative data, providing further insight into the origins of the rules and the circumstances of and motivations for their evolution. We use these methods to investigate what drives states’ foreign relations law choices.

We find that, even in the twenty-first century, foreign relations law continues to be shaped primarily by legal origins and colonial legacies, and that few countries appear to deploy their foreign relations laws in pursuit of specific objectives such as international credibility or democratic commitment. Our data show that a small number of models of foreign relations law emerged in the nineteenth and early twentieth century in Western Europe, where they solidified, later spread through colonial channels, and usually survived decolonization. Where countries depart from received models, the changes are usually associated with major political shifts such as post-war reconstruction or revolution, during which countries usually open their systems to international law. But notably, authoritarian backsliding rarely leads to increased doctrinal hostility toward international law. The bulk of foreign relations law remains standardized, reflecting countries’ legal origins and colonial heritage.

These findings challenge theories that understand foreign relations law as a tool strategically deployed to further states’ domestic and international interests. Prominent scholars working in political science have focused on foreign relations law as a means of making commitments more credible in the eyes of the international community. In this account, design choices such as involving the legislature in treaty-making and empowering courts to enforce international law signal to potential treaty partners that a country will keep its promises.Footnote 8 Others have linked foreign relations law choices to democracy and democratization, postulating that democratizing countries seek a larger role for their legislature in treaty-making and make treaties directly applicable by courts to lock in their commitments to human rights and democracy.Footnote 9 These leading accounts share functionalist premises: they contend that foreign relations law rules serve specific purposes and, implicitly, that policymakers design them to serve each country's distinctive needs.

Our findings suggest that foreign relations law is usually far less deliberate and strategic than these accounts assume. Our mapping of the data shows no discernible correlation between foreign relations law doctrines and measures of democracy or proxies for the need for international credibility. While functionalist accounts may hold explanatory power in specific cases, our analysis reveals that most of foreign relations law continues to be shaped along colonial lines, even post-independence. Footnote 10

The remainder of this Article is organized as follows. Part II describes the leading theories articulated for why states choose foreign relations law models. It starts from the well-known distinction between monist and dualist approaches and describes how these approaches are commonly associated with the civil law and common law traditions, respectively. Although conquest and colonization drove initial similarities in foreign relations law within legal families, independent states are free to change their foreign relations law arrangements. While they may continue to be influenced by their received legal tradition, states may also tailor foreign relations law to their unique needs or converge upon a common global model. In fact, leading accounts in political science offer functionalist explanations for foreign relations models that focus on states’ desire for international credibility or on democracy and democratization. In these accounts, one would expect states to make similar foreign relations law choices only if they have similar functional needs.

Part III describes our original dataset and the methods we use to analyze it. The most important method is a form of spatial scaling, which uses our quantitative data to plot a point on a two-dimensional graph that represents each state's policy choices for each year. This allows us to map the policy positions of states relative to each other, identify clusters of states that follow similar policies, and track how these policies (and the clusters) shift over time.

Part IV describes the basic findings we derive by mapping contemporary foreign relations law doctrines. It first shows that foreign relations law choices are standardized: countries cluster around a relatively small number of models whose basic features are similar. It further shows that there is little discernible correlation between foreign relations law choices, on one hand, and measures of democracy and of the rule of law (which we treat as a proxy for a state's need for international credibility), on the other. By contrast, countries clearly and strongly cluster together based on their civil-law or common-law origins. This pattern indicates the persistent influence, even post-independence, of legal origins and colonial history across countries, even those that otherwise differ widely in democratic credentials, economic development, and international political alignment.

Part V dives into the worldwide historical development of foreign relations law doctrine. Using a combination of qualitative narrative and spatial maps generated at critical historical junctures, it shows how standardized models of foreign relations law emerged in the nineteenth century. The basic features of these models—broadly associated with Continental Europe, Latin America, and Great Britain—solidified by the beginning of the twentieth century. They then underwent some meaningful changes driven by that century's upheavals, especially the World Wars, and later diffused broadly as decolonization led to the emergence of numerous new states. Despite their anti-colonial stance, new states almost always continued the foreign relations law regimes inherited from colonial powers, modifying them gingerly and gradually, if at all. Part V traces the further evolution of these models through the rise of authoritarian regimes in the 1970s and 1980s and the wave of democratization that followed the end of the Cold War. Only in the latter period does the democratization thesis find stronger support, as Eastern European and Latin American countries consciously enshrined international law as a buttress against authoritarianism and human rights violations. Yet even today, colonial origins remain the primary predictor of foreign relations law choices. Part VI concludes.

Our investigation makes several important contributions. In its geographical and chronological scope and in the range of sources considered, it surpasses any prior effort to document foreign relations law worldwide. It goes beyond well-documented Western states and familiar English-language sources to encompass dozens of countries in the Global South and sources in multiple languages. It also expands on traditional qualitative approaches by analyzing original quantitative data, including year-by-year measures of treaty-making hurdles and the status of international law across different legal systems. These data will assist researchers across disciplines in studying states’ engagement with international law. On the theoretical front, our analysis reveals that colonial ties continue to be influential even decades post-independence, continuing to shape the bulk of foreign relations law. At the same time, our qualitative analysis reveals that functionalist accounts appear to have explanatory power in some countries and periods, contributing to a better understanding of these theories’ mechanisms and scope of application. Finally, our analysis might help shape more effective international governance and constitutional design.

II. The Drivers of Foreign Relations Law

A. The Monist-Dualist Divide

International legal scholars traditionally analyze the relationship between domestic law and international law from the perspective of the monist-dualist divide.Footnote 11 The canonical formulation of this distinction holds that under the monist approach, which “regards international law and national law as two parts of a single system,” international law “automatically passes into the state's national legal system” and “stands ‘higher’ in the hierarchy of legal norms” than national law.Footnote 12 By contrast, the dualist approach “regards international law and national law as separate legal systems,” so that international law “does not automatically become a part of the national law”; it does so only “when it has been ‘transformed’ or ‘incorporated’ into national law by an act at the national level, such as the enactment of an implementing statute for a treaty.”Footnote 13

The monist-dualist distinction's usefulness as an explanatory model is widely debated. Although the theory remains influential, many scholars have observed that the distinction has limited ability to explain the actual foreign relations law arrangements across national legal systems.Footnote 14 In fact, no system is strictly monist or dualist: the theories are ideal types that do not exist in the real world.Footnote 15 Thus, scholars in this field often warn that researchers should focus on specific questions, such as whether treaties are directly applicable in domestic courts and how courts resolve conflicts with statutes, rather than on general characterizations of a national system's approach.Footnote 16 Nevertheless, the monist-dualist distinction remains the classical analytical starting point for classifying national approaches toward international law.

The monist-dualist distinction, in turn, is widely seen as connected to the civil and common law legal traditions. In his influential textbook, James Crawford observes that, while there is no single civil law approach to the reception of international law, civil law systems tend to be monist with respect to both treaties and international custom.Footnote 17 By contrast, Crawford observes that common law systems tend to be dualist with respect to international treaties and monist with respect to custom.Footnote 18 In the United Kingdom, the dualist approach to international treaties is often linked to the country's tradition of parliamentary sovereignty: because parliament is sovereign, international treaties cannot create law directly or override domestic legislation.Footnote 19 In civil law systems, monism is often linked to the hierarchy of the sources, an influential doctrine in the civil law tradition.Footnote 20 Hans Kelsen, the most famous exponent of this doctrine, argued that every legal order can ultimately be traced back to a basic norm (the “Grundnorm”).Footnote 21 Because there must be a single source of authority for all law, Kelsen believed that dualism was logically impossible, as it would require there to be more than one basic norm.Footnote 22

The presumed mechanism that drives the correlation between the common law and dualism, on one hand, and the civil law and monism, on the other hand, is conquest and colonization. Comparative law scholarship has long documented that, as British, French, and Spanish colonizers acquired overseas territories, they transplanted large portions of their legal system to their colonies.Footnote 23 Former British colonies inherited much of their legal system from the United Kingdom and became common law legal systems, while former French and Spanish colonies inherited their legal systems from France and Spain and became civil law legal systems.Footnote 24 A host of studies has shown how “legal origins” continue to shape the substance of many areas of laws around the world, including investor protections and property rights.Footnote 25 Even constitutional law, which is often viewed as a distinct expression of national identity, reflects these influences.Footnote 26 Empirical studies of the content of the world's written constitutions find that much of that content is standardized, with countries falling into two primary families that correlate strongly with the civil law and common law traditions.Footnote 27 The same mechanisms might explain similarities in foreign relations law.

Of course, legal families are not set in stone.Footnote 28 After independence, states generally become free to change their foreign relations law. Of course, that does not mean that doing so is necessarily easy. In some cases, there may be institutional obstacles, as some foreign relations law changes require formal constitutional amendment. There may also be cultural barriers, such as legal elites who prefer the existing system. Even so, there is also reason to believe that such change is possible. In many constitutional systems it is relatively easy to amend or replace the constitution.Footnote 29 Even without changes to the constitution's text, courts can modify their interpretations. What is more, much of foreign relations law is sub-constitutional in nature. In many Eastern European countries, for example, organic laws codify the main foreign relations law choices and can be amended through legislation. In most common law countries, much of foreign relations law is judge-made, meaning that judges have some power to change its rules. Thus, while there is no doubt that there may exist important path dependencies, it is reasonable to expect that foreign relations law may change at least somewhat post-independence.

One possibility is that legal norms continue to diffuse inside legal families after independence. As Holger Spamann points out, countries within a legal family often share the same language and elite lawyers receive their legal education in the colonial metropolis, producing shared legal norms and reasoning. The result might be an ongoing diffusion of legal norms within legal families, driven by the professional commitments of judges, legislators, and regulators alike.Footnote 30 This type of diffusion can continue to shape foreign relations law even decades post-independence. Constitution-makers might follow the foreign relations law practices that prevail within their legal tradition; and the same might be true for lawmakers and courts. Indeed, our own analysis found numerous instances in which judges simply followed long-established common law or civil law practices in landmark foreign relations law cases. To give one example, when the Indian Supreme Court held in 1980 that treaties are not self-executing under Indian law, it relied on British precedent, despite having been independent for thirty-three years.Footnote 31

Another possibility is that countries gradually drift away from colonial models and instead converge on a single global model.Footnote 32 A school of thought in sociology—sometimes referred to as the “world polity school”—holds that states adopt law and institutions not because those particular choices rationally further the state's goals but because they are following a common cultural script.Footnote 33 Legal scholars have applied these insights to different areas of law, observing that many elements of national legal systems reflect the cultural influence of a global world polity.Footnote 34 To illustrate, empirical studies show that states adopt constitutional rights,Footnote 35 human rights agreements,Footnote 36 and environmental laws,Footnote 37 not because they fit their local needs and circumstances, but because these are part and parcel of the global cultural model.Footnote 38 Foreign relations law might similarly be shaped by world culture.Footnote 39 Indeed, some scholars have drawn attention to the emergence of common values relating to domestic law's relationship toward international law.Footnote 40 Thus, countries may converge upon a global model that transcends traditional legal families.

Divergence is also another possibility. Upon independence, states may customize and tailor their foreign relations law choices to their own needs. Specifically, they might strategically deploy foreign relations law to make their treaty commitments more credible or to entrench democratic reforms. We discuss these strategic considerations below.

B. Functionalist Theories

The political science literature offers different strategic accounts for why states might adopt or update their foreign relations law arrangements. These accounts broadly emphasize two different strategic considerations: (1) a desire for credibility in the international arena; and (2) democratization and a desire to lock in democracy. The premise behind both of these theories is that countries deploy their foreign relations law strategically, to further specific goals. Importantly, strategic accounts and the legal origins theory are not mutually exclusive: countries that inherited certain models may subsequently engage in reform to further specific interests.

1. Credible Commitments

The idea that foreign relations law can be used to improve a state's international credibility can be traced back to the U.S. founding. Under the Articles of Confederation, the central government found itself powerless to enforce international law obligations. State governments and courts disregarded the nation's treaties and failed to provide remedies for international law violations by individuals, spurring tensions with European powers.Footnote 41 The solution was simple and widely agreed upon: treaties would be made part of “the supreme Law of the Land,” and federal courts would be empowered to enforce them.Footnote 42 John Jay captured this reasoning in the Federalist Papers: “a treaty,” he wrote, “is only another name for a bargain, and . . . it would be impossible to find a nation who would make any bargain with us, which should be binding on them absolutely, but on us only so long and so far as we may think proper to be bound by it.”Footnote 43

Over two hundred years later, political scientists and legal scholars continue to explore different legal strategies to strategically improve a country's international credibility.Footnote 44 The question is not merely academic: policymakers and diplomats know how critical national credibility can be in concluding international agreements on matters such as trade, investment, and national security. Like the early United States, many states today struggle to assure potential treaty partners that their commitments are real.

One way to make international legal commitments credible is to ensure that treaties are enforceable in domestic courts.Footnote 45 The U.S. framers did so by making treaties equal in status to federal law. Many constitutions today likewise stipulate that international agreements apply directly, thereby empowering domestic courts to enforce these agreements. Making treaties superior to domestic law might improve international credibility even further. When treaties take priority over domestic statutes, domestic courts are empowered to invalidate inconsistent domestic laws. Although the U.S. framers did not take this approach, many newer constitutions do. When courts can use international law to constrain domestic policy, this sends a signal to potential treaty partners that a state's promises are less likely to be broken, thereby making a formal agreement more appealing to that partner. Footnote 46 As a result, a state might be able to conclude more treaties and perhaps to secure more favorable terms.

A different way in which international credibility might be improved is by requiring the executive to seek legislative approval of treaties prior to ratification. Political scientists and legal scholars have proposed various theories to explain how such constraints may increase the credibility of treaty commitments. First, the legislative approval process may generate information that allows potential treaty partners to evaluate the likelihood of future non-compliance or withdrawal.Footnote 47 In contrast with executive action alone, a legislative vote demonstrates broader domestic support for the treaty, increasing partners’ confidence that compliance will survive changes in the executive. The public debate the vote generates also reveals information on the preferences of important domestic political actors, such as opposition politicians and interest groups, who may influence future compliance.Footnote 48 In the case of treaties that require further legislation to become effective, a positive vote also increases confidence that the legislature will adopt the necessary legislation. The availability of this information may thus enhance the credibility of the country's treaty commitments.Footnote 49

In addition to this information-generating function, legislative involvement in treaty-making may also serve a signaling function. Submitting a treaty for legislative approval is politically costly for the executive because she needs to spend political capital to secure its approval. Partners observe that the executive is willing to incur these costs, which suggests to them that the leader sincerely intends to commit to the treaty long enough to reap its cooperative benefits. To illustrate, consider the U.S. Constitution's requirement of treaty approval by two-thirds of the Senate. This process is a costly hurdle for the president. The Senate leadership must be courted to place the treaty on the agenda; individual senators must be lobbied to vote in favor; even a handful can delay or block approval; and failure of a treaty in the Senate has political costs for the president.Footnote 50 It would make little sense for her to devote time and energy to obtaining approval if participation in the regime were not valuable to the administration. Thus, if she chooses to do so, treaty partners may see the commitment as more credible.Footnote 51

Thus, if these credibility theories have explanatory power, we would expect that countries that seek greater international credibility would adopt several policy measures: (1) making treaties directly applicable in their domestic legal systems; (2) elevating their status vis-à-vis domestic law; and (3) requiring more legislative involvement in treaty-making.Footnote 52

2. Democratization

There is another strategic objective that states can further through foreign relations law: entrenching their domestic commitment to democracy. Theories that link foreign relations law to democracy were developed primarily in the context of the 1990s democratization wave. They fit within a broader strand of political science research that explores the relationship between democratization and foreign affairs.Footnote 53

Scholars have long observed that democratization often goes hand in hand with growing openness toward international law.Footnote 54 Influential accounts observe this relationship for Eastern Europe and Latin America in the 1990s, especially for human rights treaties.Footnote 55 Based on 1990s trends in Eastern Europe, Andrew Moravcsik argues that new democracies commit to human rights treaties to delegate enforcement of democratic and liberal values to established external bodies, because their own rights-protecting institutions are nascent or weak.Footnote 56 This delegation locks in these values and reforms against the threat that new leadership will threaten or reverse them.

A prominent way of locking in reforms is by giving treaties direct effect in the domestic legal order and elevating their status vis-à-vis domestic law.Footnote 57 Under such a system, domestic courts can set aside domestic legislation that conflicts with human rights treaties. Not even the legislature can override the treaty: the government must secure a constitutional amendment to breach it, which is usually more difficult than amending ordinary legislation.Footnote 58 Arguably the strongest pre-commitment strategy is to give treaties constitutional rank.Footnote 59 Doing so means not only that treaties can be used to set aside ordinary legislation, but that the constitution itself is interpreted in light of international treaties. In effect, states that follow this approach delegate the interpretation of some of their constitutional commitments to international bodies.Footnote 60

Scholars have also linked democratization to higher levels of legislative involvement in treaty-making.Footnote 61 As treaties cover a growing number of areas that fall within the traditional realm of domestic legislation—including human rights, the environment, and economic regulation—greater legislative involvement in treaty-making ensures that the executive does not encroach upon the legislature's powers. Without such a requirement, the executive might bypass a recalcitrant legislature and substitute a treaty for domestic legislation.Footnote 62 Thus, separation of powers concerns may motivate giving the legislature a larger role in treaty-making.

Thus, if these theories linking foreign relations law to democratization have explanatory power, we would expect that there is a link between democracy and: (1) making treaties directly applicable in their domestic legal system, with either constitutional or statutory rank; and (2) having higher levels of legislative involvement in treaty-making and implementation. We would especially expect that new democracies would adopt these features, to lock in democracy. But because of these processes, we may also observe more generally that democracies are more likely to possess these features.

III. Data and Methods

A. New Global Dataset

How domestic legal systems deal with international law has long interested international lawyers, but our original dataset is the first of its kind. Existing initiatives are less systematic or more limited in scope. For instance, both Oona HathawayFootnote 63 and the Comparative Constitutions ProjectFootnote 64 have collected information on the domestic status of international law based on the constitution alone. Yet, many relevant aspects of a domestic legal system's relationship to international law are found not in the text of the constitution, but in legislation, case law, practice, and executive orders. Our dataset goes beyond the text of the constitution and incorporates information from these other sources. In addition to quantitative coding of constitutions, several qualitative surveys offer more in–depth information. However, such surveys cover a small number of countriesFootnote 65 and issues,Footnote 66 and they capture only one period in time. Our dataset traces the development of foreign relations law for 108 countries for the period 1815–2013.

The first step in building our dataset was to identify and define the substantive issues that define a state's relationship with international law. We identified fifty such issues, dealing with, among other things, the procedures for treaty ratification, the status of treaties in domestic law, the status of CIL, and interpretative approaches by courts. Appendix 1.A contains the full survey instrument. For each country, we commissioned a written memorandum that provides a narrative answer to each of the questions, using information from the constitution, court decisions, legislation, and secondary sources. Footnote 67 The memoranda also document how the answers have changed over time. For some systems, especially older countries that underwent frequent changes, we commissioned foreign legal experts to write these memoranda; in other cases, they were written by the authors or law students who had received training on how to research foreign relations law. Where multiple interpretations of foreign relations law existed, we relied on the most authoritative source of that system to reconcile them. All reconciliations were made by the authors. We next coded these memoranda, quantifying their information along fifty numerical variables. All coding was conducted by one of the authors.

The resulting data allow us to accomplish several different things. First, the information from the country memoranda and the resulting coding allow us to explore the origins of particular foreign relations law choices and how they spread. That is, we can provide a historical account of where certain choices first emerged and how they subsequently spread globally. Second, we can explore and visualize trends by describing and analyzing our quantitative data. And third, we can use more sophisticated techniques to analyze and explore our data. In what follows, we use a statistical technique called “ideal point estimation,” which allows us to represent countries’ foreign relations policy choices spatially and track how these choices have evolved over time. The strength of these methods is that they allow us to provide a bird eye's view of foreign relations law. The trade-off is that the approach's focus on breadth comes at the expense of depth; we do not delve into the politics of adoption in specific countries, as process-tracing or other qualitative methods would allow us to do. Moreover, although our memoranda and resulting coding capture changes beyond the textual constitution, such as executive orders and judicial interpretations, they include only formal legal changes, so not, for example, changes in political attitudes or the relative importance of formal legal rules.

B. Methodological Approach: Spatial Representation of Foreign Relations Law Preferences Through Policy Points

We use ideal-point estimation to identify and describe the principal ways in which states’ relationship to international law in their domestic legal order can vary over time—that is, the historical dimensions of foreign relations law. An ideal point or policy point represents the set of policies that an actor thinks is ideal, i.e., which it prefers over all other alternatives. Each state has a policy point along one or more underlying dimensions, which represent the salient issues that divide states in foreign relations law. We can graphically depict these policy points and dimensions, showing how states’ policies relate to each other and change over time.Footnote 68

To understand the intuition behind this method, it is useful to consider how it has been used in other contexts. Among other things, ideal-point estimation has been used to study members of the U.S. Congress,Footnote 69 justices on the U.S. Supreme Court,Footnote 70 member-states of the UN General Assembly,Footnote 71 and constitution-drafting processes.Footnote 72 The recorded behavior of these actors—be they the yea and nay votes of lawmakers, the decision making of judges, or the drafting choices of constitution-makers—can be used to determine the most salient issues that unite or divide actors and to estimate their policy points along each of these dimensions. For example, U.S. Supreme Court justices vary mainly along one dimension: how liberal or conservative their judicial ideology is.Footnote 73 Each justice's ideal point encompasses all the information from her voting record, and justices vary on this dimension based on their relative liberalism/conservatism. This dimension is “latent,” that is, not directly observed. Researchers did not determine the ideal point by asking justices whether they were liberal or conservative; rather their ideal points were inferred from their voting behavior over many cases. Similarly, when analyzing the voting records of states in the UN General Assembly through 1996, one latent dimension explains states’ voting: whether a state is associated with the United States and the West, or with the former Soviet bloc and several rising powers.Footnote 74

Political bodies can also divide along multiple dimensions. For example, the U.S. Congress during the 1960s varied along two distinct dimensions: economic-related issues and civil rights-related ones. Each member's ideal point might therefore have two values: one indicating his record on economic bills, and one indicating his record on civil rights issues.Footnote 75 The fact that these are two distinct dimensions implies that knowing a member's record on an issue like taxes would not reveal much about his voting record on issues like voting rights or segregation. In more recent decades, however, the U.S. Congress has converged to one dimension. That means that a member's voting record on taxes should predict her voting record on issues like LGBT or voting rights.Footnote 76

We adapt this widely used method here and, for the first time, apply it to states’ foreign relations law choices. To do so, we first code thirty-one attributes of states’ foreign relations law, based on the dataset described above. Those thirty-one attributes include issues like whether treaties and international custom apply directly in the domestic legal order, the relative status of treaties in the state's legal hierarchy, the status of CIL in that hierarchy, and which branches of government are empowered to bind the state by ratifying a treaty. Appendix 1.B lists all thirty-one variables.

Next, for each of these thirty-one traits, we identify each state's position on that trait for each year, treating it as a preference or “vote,” either for or against the policy for that year. For example, we code whether or not treaties apply directly in the domestic legal order and whether or not they enjoy equal (or greater) status as national legislation. Of course, states do not usually cast annual “votes” per se to determine the different aspects of their foreign relations policies. Nonetheless, we can still conceive of each state's making a decision each year about the rules it prefers, either by retaining the status quo or by adopting a new rule through constitutional amendment, statutory enactment, judicial reinterpretation, or other means. We can therefore treat its expressions of preferred policy as if they were votes and, in turn, use them to estimate states’ policy points along one or more dimensions.Footnote 77

Note that, while this method allows us to more clearly observe relationships between state traits (e.g., being in Europe, having a common-law origin, or being a former colony) and state foreign policy choices, it cannot by itself establish that those traits caused those policy choices. Nonetheless, we use the method because graphically observing the relationships between traits and policies starts to paint a picture hinting at a possible causal story, which we further explore with the historical account in Part V.

IV. Basic Findings

The data reveal that states’ foreign relations legal designs comprise choices that vary principally along two distinct dimensions: (1) the legislature's role in treaty-making; and (2) the status of international law in the domestic legal order. These two dimensions explain roughly 60 percent of the variation in countries’ foreign relations legal choices.Footnote 78

A. The Two Dimensions

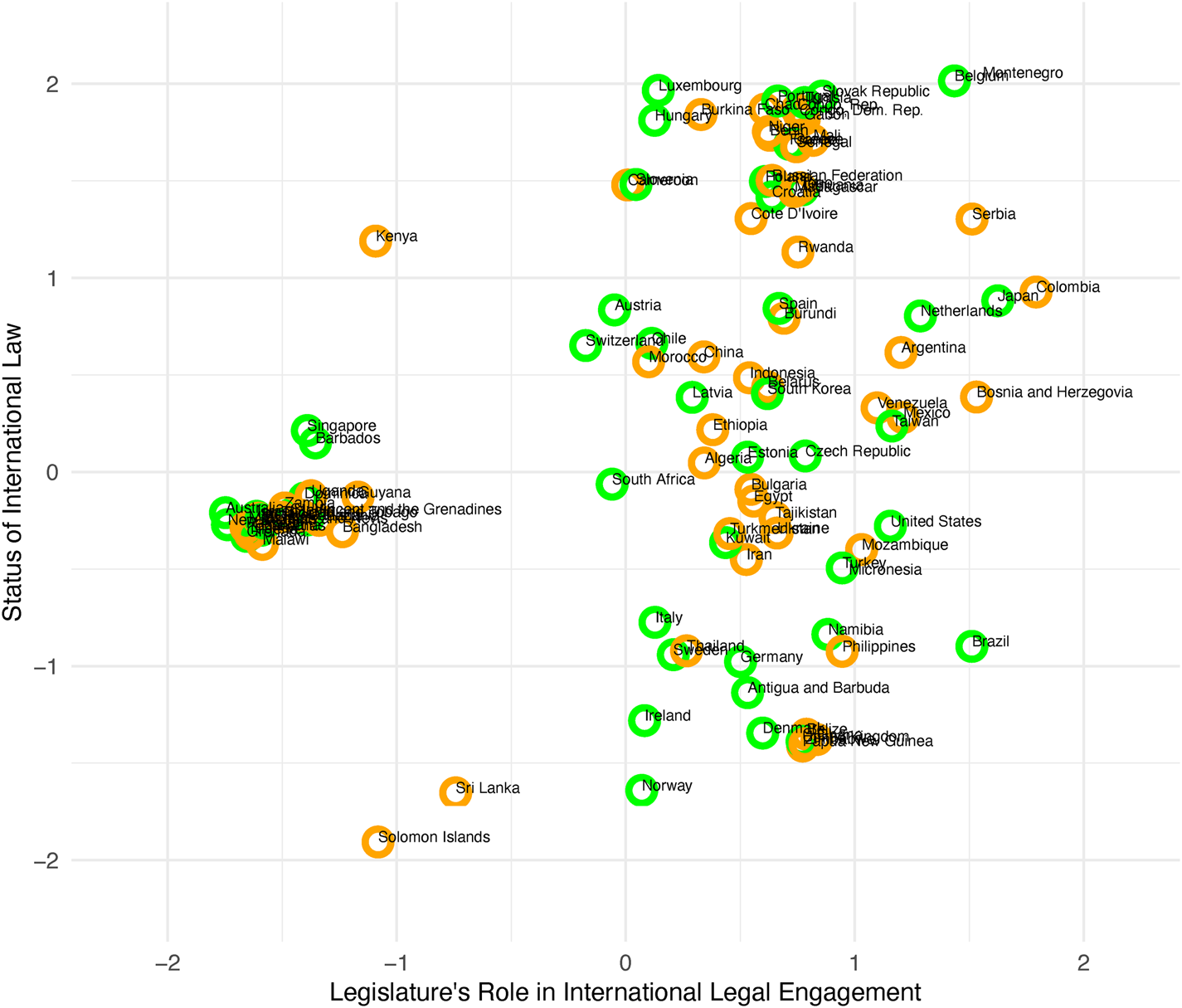

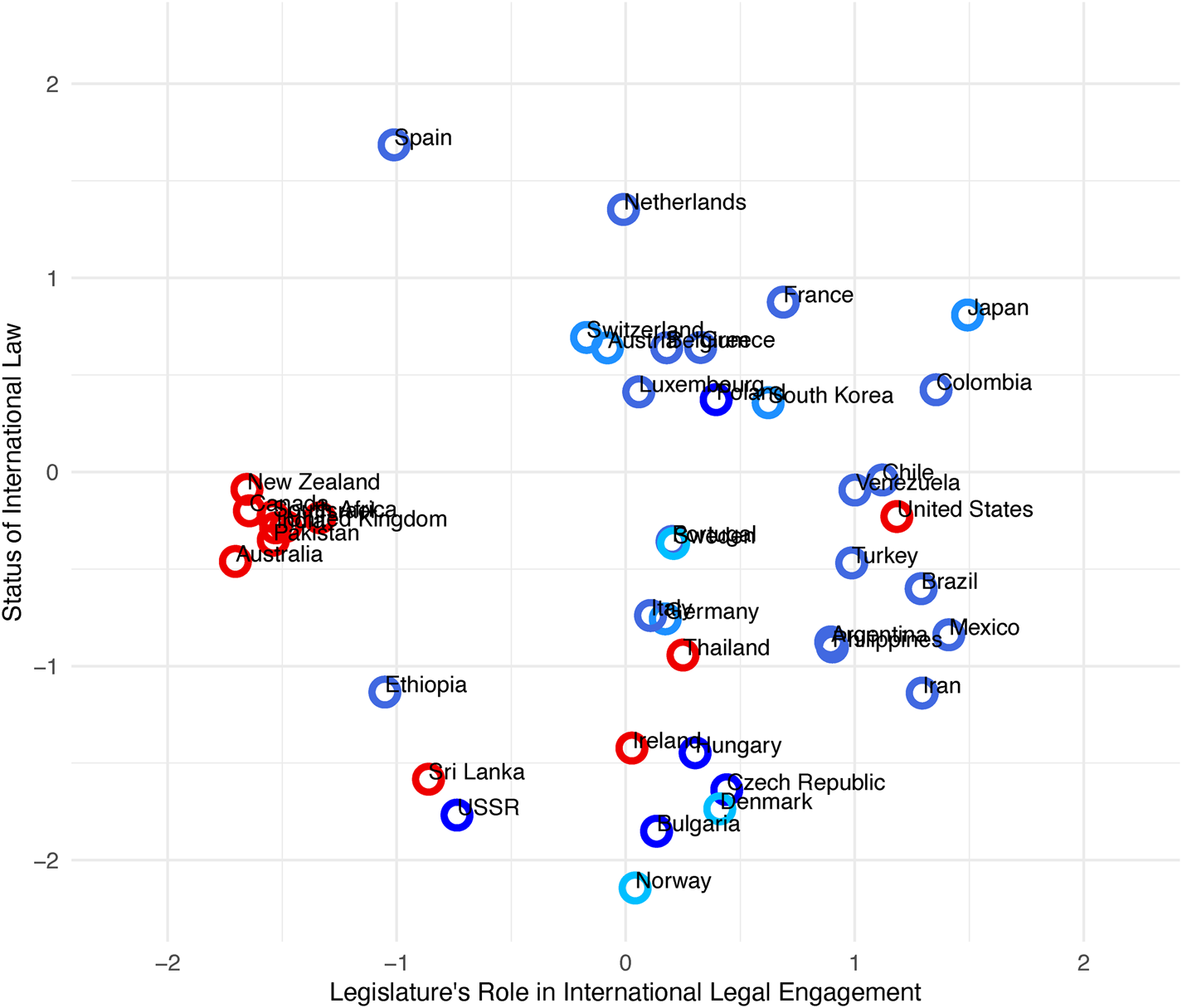

Figure 1 uses the ideal-point estimation technique described in Section III.B to depict states’ policy points along these two dimensions in the year 2010. Figure 1 notes some important or noteworthy states: France, the United Kingdom, China, Russia, India, Belgium, and the United States. One tool to establish the meaning of these two dimensions is to identify the most extreme countries on each dimension based on their policy points and to inspect whether and how their foreign relations choices are unusual, which likely cause at least some of their extreme positions on the dimensions.Footnote 79 Figure 1 notes those countries that represent extremes in each of the two dimensions: Australia and Colombia on the first (x-axis) dimension, and the Solomon Islands and Montenegro on the second (y-axis) dimension.

Figure 1. Policy Points in Two Dimensions for Key and Extreme States, 2010

Consider the first dimension, which we characterize as “the legislature's role in international legal engagement.” This dimension captures distribution of power over treaty ratification: whether treaties require legislative approval and whether the requirement includes all treaties or just certain types; whether that legislative approval vote is binding; and whether the executive can conclude executive agreements on her own without legislative consent. This dimension also captures some aspects of the status of treaties: on the left of the plot, we have the dualist countries, which require treaties to be incorporated into domestic law through legislation; on the right, we have countries that not only apply treaties directly without legislative action, but also make them superior to domestic legislation. Countries that apply treaties directly but make them inferior or equal to ordinary laws fall somewhere in the middle. These two aspects of the first dimension both relate to the legislatures’ role in treaty-making: they capture legislative involvement ex ante in the process of committing to a treaty, and ex post in passing implementing legislation.

On this first dimension, Australia, along with a cluster of other common law countries including India, sit farthest to the left. These are all countries where the legislature is involved ex post but not ex ante. That is, the head of government in these countries enjoys substantial authority to bind the state and need not seek the parliament's permission. However, treaties need to be incorporated by statute to have domestic legal effect. Note that the United Kingdom is not part of this cluster. It followed the same approach until it introduced parliamentary approval requirements in 2010, thereby moving it significantly rightward on the plot.Footnote 80 The United Kingdom is surrounded by a second cluster of common law countries, including Belize, Zimbabwe, and Papua New Guinea, which likewise have introduced parliamentary approval requirements.

On the far right of the first dimension lie countries like Belgium, Montenegro, and Colombia. These countries have strong monist systems and make treaties superior to domestic legislation, thus allowing no role for the legislature ex post and allowing treaties to trump future legislation. However, they do ensure legislative involvement ex ante through legislative approval requirements that bind the executive. Indeed, in the countries on the far-right side of this dimension, all treaties require legislative approval. (For those in the middle, some but not all treaties require legislative approval). As can be seen from Figure 1, the United States falls right of the middle on this dimension, reflecting that many (but not all) treaties require congressional approval and that some treaties do apply directly, even though they can be overturned by subsequent legislation.

We characterize the second dimension as “the status of international law in the domestic legal order.” Generally speaking, countries that make treaties superior to legislation place high, while countries that make treaties equal or inferior to legislation place near the middle, and countries that require some, most, or all treaties to be incorporated by legislation closer to the bottom. In addition to capturing the domestic status of treaties, this dimension also incorporates information on the status of CIL, which is often different from the status of treaties. Indeed, among the states with the highest scores on this dimension are those that not only make treaties superior to domestic law but do the same for CIL (e.g., Belgium, Montenegro, and Portugal). Conversely, the countries with the lowest score on this dimension are those like the Solomon Islands and Sri Lanka, which do not apply treaties directly and make CIL inferior to statutes or deny it any direct effect.Footnote 81 The United States again lies in between, slightly closer to the dualist end (bottom) of the spectrum: so-called “self-executing” treaties apply directly and are equal to ordinary statutes, while CIL applies directly but is inferior to domestic law.Footnote 82

It is worth mentioning that the decision whether or not to apply treaties directly is important on both dimensions.Footnote 83 Notably, a policy choice not to make treaties directly applicable means that treaties fall outside the national legal hierarchy, which is central to the second dimension. But it also implies a further role for legislatures, whose intervention is required to make the treaty binding on domestic public or private actors. The fact that the basic choice of what status to give treaties in the domestic legal order bears on both dimensions makes it one of the most distinguishing features of a country's foreign relations law model.

In sum, our analysis reduces more than thirty foreign relations law choices to a two-dimensional plot. Where states made similar policy choices about the legislature's role in treaty-making, they cluster together horizontally (left and right). Where two states made very different choices, they are separated horizontally, with the states giving their legislatures smaller roles lying on the left side of the plot and states giving their legislatures larger roles lying on the right side of the plot. Where states made similar choices about the relative status of international law in their domestic legal orders, those states cluster closely together vertically (top and bottom). States that give international law higher status lie close to the top of the plot, while states that give it lower status lie toward the bottom.

C. Explaining Country Clusters

Where two countries lie close together on the two-dimensional plot, it means that they share similar scores on both the first and second dimensions. In other words, they made similar foreign relations law choices.

Above, we posited several hypotheses about the factors that lead states to adopt similar or different foreign relations laws. Traditional theories from comparative law predict that their foreign relations law choices are mostly explained by a country's colonial heritage.

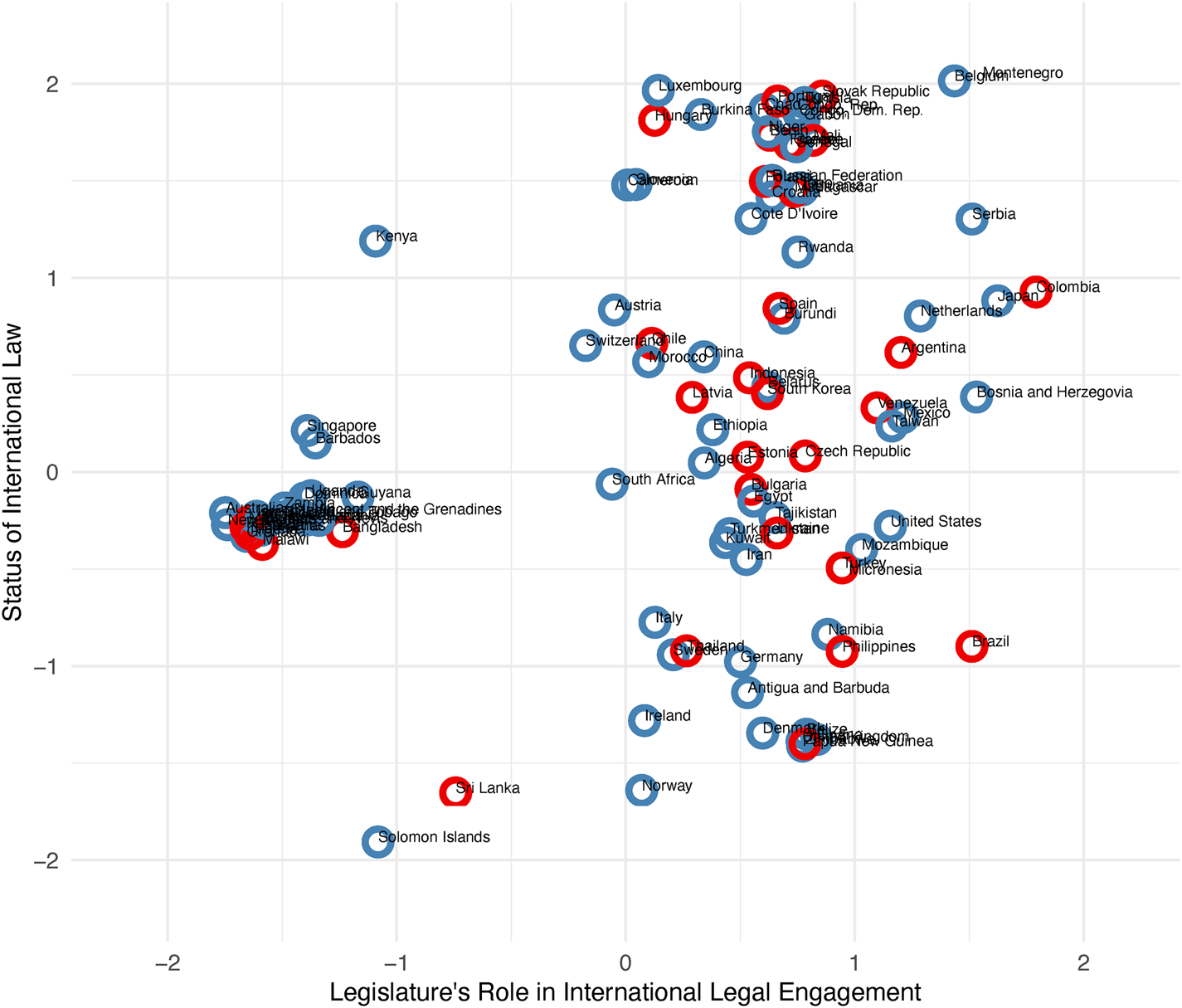

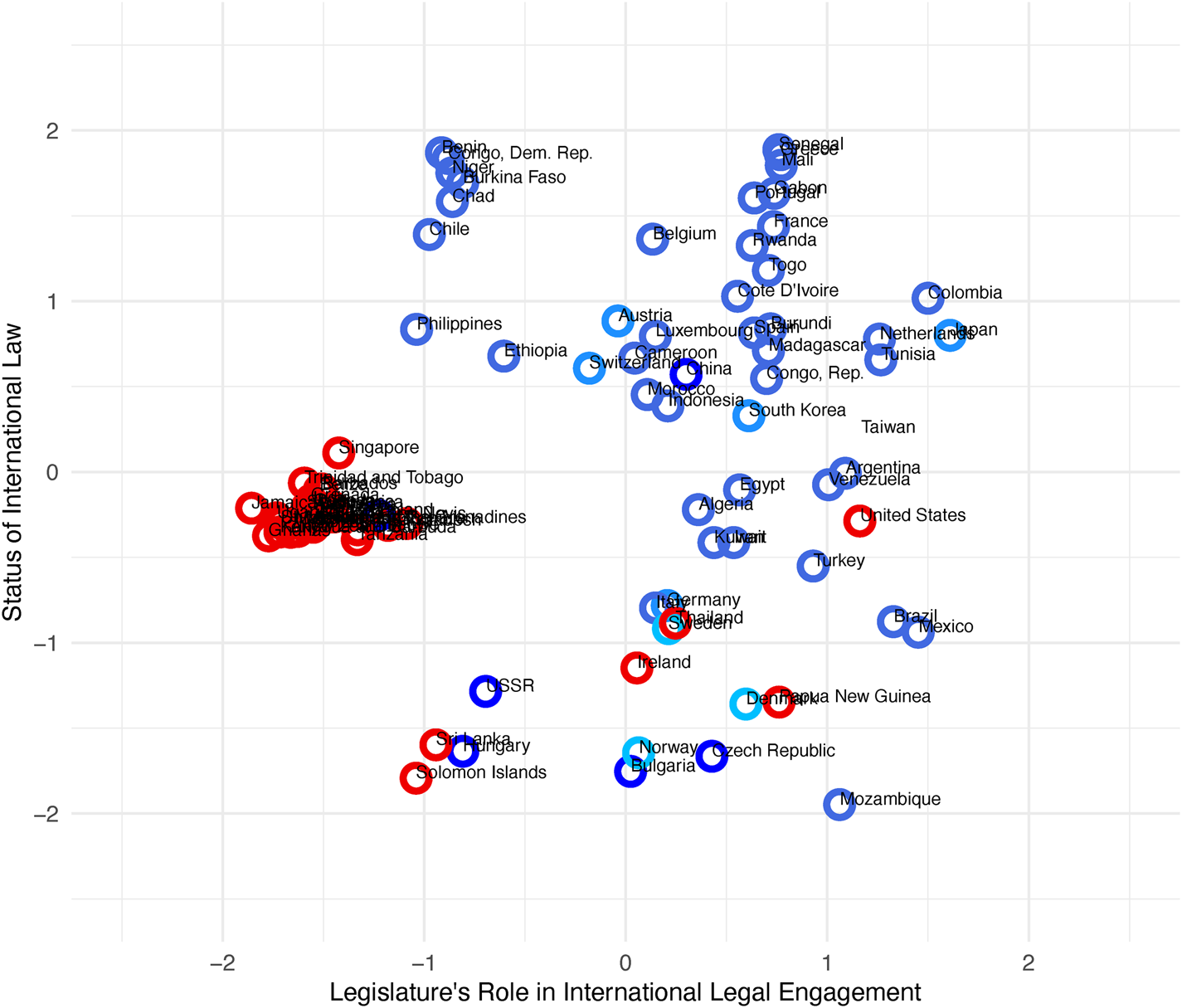

To explore these prediction, Figure 2 reproduces the same spatial 2010 plot from Figure 1 but highlights all the common law systems in red and the civil law systems in blue.Footnote 84 (Countries with socialist, French, German, and Scandinavian legal origins—all considered subgroups of the civil law tradition—are highlighted in different shades of blue: navy, royal, azure, and sky blue, respectively.) The plot reveals a stark divide between common law and civil law countries. In general, the common law countries are clustered in the bottom left of the plot, while the civil law countries are clustered in the top right. Indeed, we can draw a straight, diagonal line on the plot that partitions the universe of states between common and civil law with fairly high accuracy. The only common law countries on the “wrong,” i.e., civil law, side of the line are the United States, which never followed the traditional common law approach, and Namibia, which adopted parliamentary approval of treaties and a monist system upon independence. Only five civil law countries “erroneously” fall on the common law side of the line: Germany, Italy, and three Scandinavian countries, which are dualist with respect to treaties. Overall, the legal traditions have substantial explanatory power for countries’ positions on the plot.

Figure 2. Policy Points in Two Dimensions, Color-Coded by Legal Origin, 2010

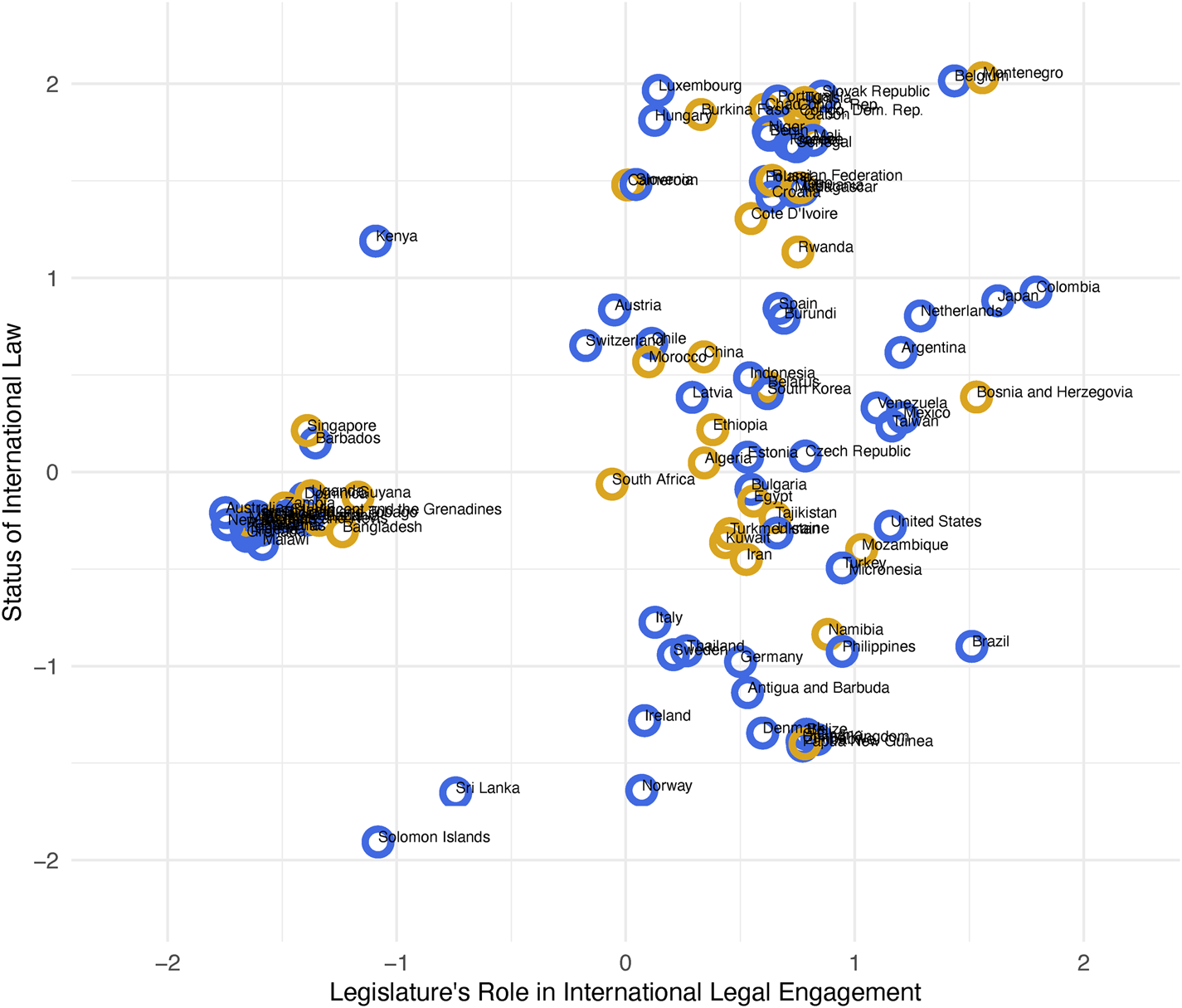

The same method also allows us to explore the extent to which other theories explain foreign relations law choices globally. Theories that link foreign relations law to a desire for credibility in the international arena predict that countries in need of international credibility will adopt legislative approval requirements, apply treaties directly, and give them higher status than ordinary domestic law. If this theory is useful, countries seeking to improve their credibility should cluster at the top right of the plot, indicating both a large role for the legislature and a high openness toward international law.

We can test this prediction by identifying the countries that benefit most from boosting their international credibility. One way to do so is by looking at a measure of states’ domestic adherence to the rule of law. For example, a capital-exporting state may worry that a host state with a weak rule of law might expropriate its investors’ assets despite any protections it secures in a bilateral investment treaty. In order to conclude such treaties and attract foreign investment, the host state may need to take steps to enhance the credibility of its commitments. As discussed in Part II, another way to identify these countries is by their democratic credentials. More specifically, newly democratizing countries, like the early United States, may need to signal that the newly established legislature is committed to the country's treaty obligations. New democracies and states with weak rule of law, therefore, are those that can benefit from deploying foreign relations law strategically and should cluster at the top right corner of the plot.

Figures 3 and 4 identify countries with weak rule-of-law and young democracies, respectively. They show that the predictions from credibility theories do not bear out. Figure 3 depicts a spatial map as of 2010 highlighting countries with strong rule-of-law traditions (in green) and countries with weak rule-of-law traditions (in gold). It does not reveal an obvious relationship between this trait and either of the two dimensions.Footnote 85 Figure 4 singles out emerging democracies (in red) versus established democracies and autocracies (in blue) and likewise shows no clear relationship.Footnote 86 This does not mean that credibility theories have no predictive value at all—they may still explain particular cases at particular times—but they do not appear to account for global patterns in the data.

Figure 3. Policy Points in Two Dimensions, Color-Coded by Weak (Gold) and Strong (Green) Rule of Law, 2010

Figure 4. Policy Points in Two Dimensions, Color-Coded by New Democracies (Red) and Others (Blue), 2010

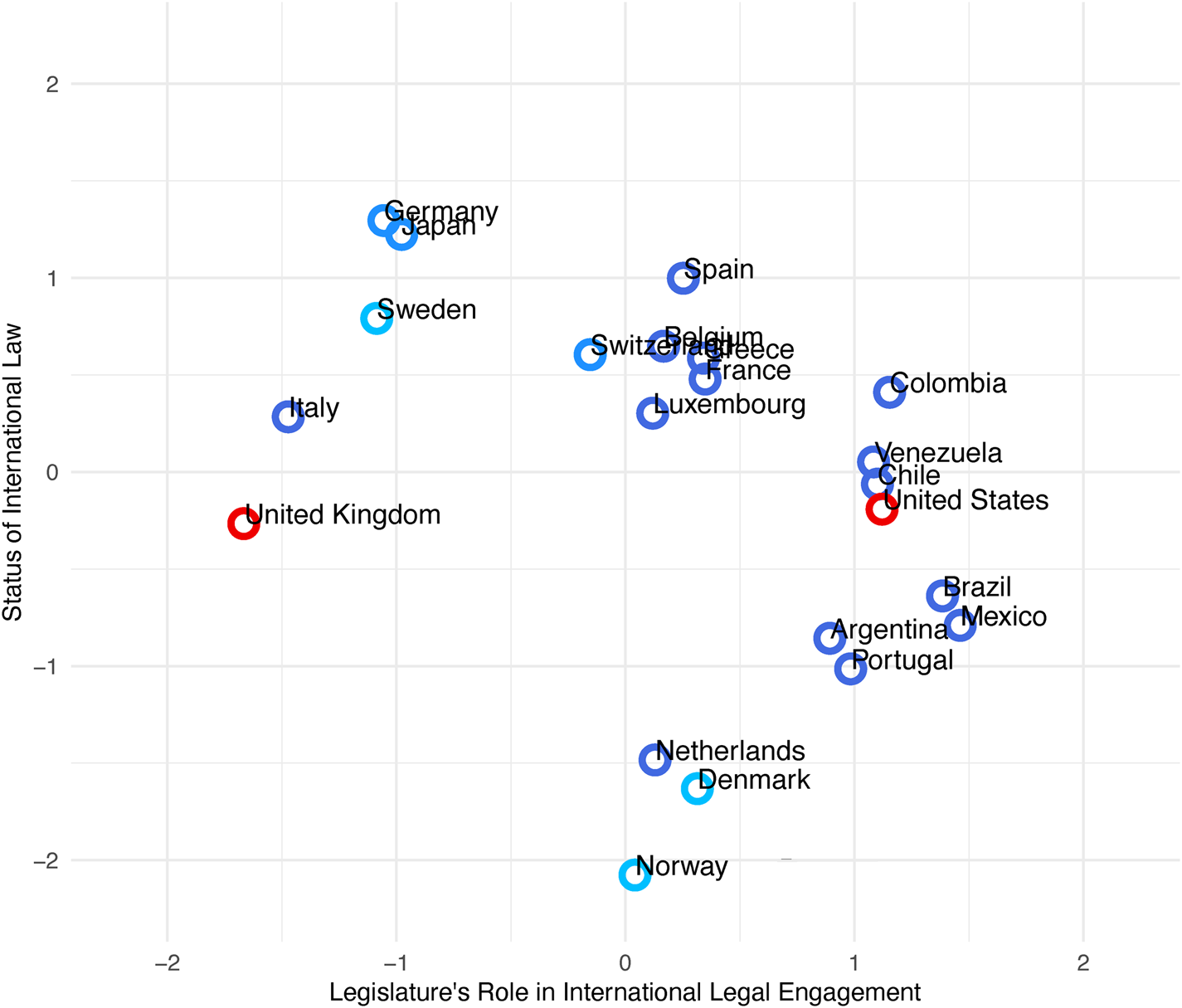

Theories that link countries’ foreign relations law choices to a desire to lock in democracy postulate that democratization goes hand in hand with a growing openness toward international law in the domestic legal system and with increased legislative involvement in treaty-making.Footnote 87 If this is so, we should expect to see countries that seek to pre-commit to democracy cluster in the top right of the spatial map. Figure 4, which highlights new democracies, shows that the data provide little or no support for this theory. Since it is difficult to capture the dynamic process of democratization with a single snapshot of the data, we also separate all democracies from autocracies. Figure 5 shows the same plot with democracies in blue and autocracies in gold.Footnote 88 It reveals that predictions that link foreign relations law choices to democracy also do not bear out for the global sample of countries in 2010: both democracies and autocracies are scattered throughout and, if anything, the bottom left of the plot is disproportionately occupied by democracies.

Figure 5. Policy Points in Two Dimensions, Color-Coded by Democracy (Blue)/Autocracy (Gold), 2010

Exploring our data through ideal-point estimation thus reveals a number of broad features of foreign relations law globally. First, foreign relations law choices are substantially standardized, but not to the point that states have converged upon a single model. Second, the civil law-common law divide largely explains how countries fall on the plot. While theories of democratization and credibility theories may have explanatory power in individual cases, they do not seem to explain the bulk of foreign relations law choices, either historically or today. By contrast, even today, whether a country has civil law or common law legal origins strongly predicts its foreign relations law choices. Third, the plot reveals that while the civil law-common law divide performs well in explaining where countries fall, the clusters are somewhat dispersed, meaning there are also important differences within these traditions. We will explore these, along with the basic divide, below.

V. Mapping and Tracing the Evolution of Foreign Relations Law

How did this small set of foreign relations legal models come to prevail around the world? In other words, what factors led countries to adopt these models and, in many cases, modify them over time? In this Part, we use our original data to trace the historical origins of the principal foreign relations legal models and their migration over four periods: the nineteenth century, the early twentieth century, the Cold War, and the post-Cold War period. By exploring and explaining how the various country clusters have shifted over time, this Part tracks the long-term evolution of global foreign relations law and provides a more detailed account of the times, places, and circumstances in which each of the three theories described above may explain foreign relations law choices.Footnote 89

A. Origins and Development of the Models (1787–1900)

The predecessors of the models that dominate today first emerged in the nineteenth century in the United States, continental Europe, Great Britain and its colonies, and Latin America. We explore each region in turn.

1. The United States and Continental Europe

The American founders debated extensively how the new nation's foreign relations law ought to be structured. As noted above, the new nation's need to demonstrate its ability to redress wrongs committed by its nationals and to secure the credibility of its treaty commitments largely drove its foreign relations law choices.Footnote 90 To accomplish these goals, the new U.S. Constitution contained several novel provisions governing the country's engagement with international law. It assigned an important role to the newly established legislature: the Senate had to approve treaties by a two-thirds majority and Congress was given the power to “define and punish . . . Offenses against the Law of Nations.”Footnote 91 It also included a Supremacy Clause that made ratified treaties part of “the supreme Law of the Land,” thereby allowing treaties to be enforced in federal court.Footnote 92 Over the course of the nineteenth century, U.S. courts further refined these choices: they confirmed that treaties applied directly but limited that application through the self-execution doctrine, and they put treaties and federal statutes on equal footing.Footnote 93

In continental Europe, these questions arose first in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, with the French Revolution and constitution-making waves that followed. Before then, most continental European countries lacked elected legislative assemblies. Likewise, while courts occasionally applied the law of nations before the nineteenth century, it was not until the rise of positivismFootnote 94 in the nineteenth century, and its greater attention to the sources and hierarchy of legal norms, that questions relating to the domestic status of treaties and CIL drew sustained attention. The proliferation of treaties and the development of international law rules in new areas increasingly forced constitution-makers, legislatures, and courts to confront these issues.

Under the old regime, treaty-making was an exclusive prerogative of the monarch. As absolute monarchy came under attack, separation of powers and legislative oversight of the executive became central battlegrounds. However, treaty-making and the status of international law were hardly at the forefront of reformers’ concerns. Influential Enlightenment political theorists, such as Montesquieu and Rousseau, thought of foreign relations as a quintessentially executive function that had little bearing on domestic conditions and which representative assemblies were poorly suited to conduct.Footnote 95 The early years of the French Revolution shattered these premises.

Revolutionary France did not face a credibility crisis, as the early United States did, but a political and military one. Following an incident between Spain—France's ally and fellow Bourbon monarchy—and England, King Louis XVI ordered naval vessels armed in preparation for war with England.Footnote 96 The prospect of war threatened the Revolution's fragile achievements. In May 1790, a heated debate in the Constituent Assembly opposed proponents of the King's traditional prerogative over foreign relations and reformers who, inspired by Enlightenment ideas, believed that unchecked royal power was the source of all wars and wished to abolish it altogether.Footnote 97

On May 22, the Assembly adopted a decree under which war could be declared only by the legislature on the king's proposal. Whereas the king had exclusive power to conduct external political relations and to sign treaties, “treaties of peace, alliance, and commerce may only be executed upon ratification by the legislative body.”Footnote 98 The decree thus classified treaties by subject-matter, with certain treaties requiring prior legislative approval while others could be concluded by the king acting alone.Footnote 99

Although this constitutional regime proved short-lived, numerous European constitutions adopted the same approach.Footnote 100 Thus, Spain's 1812 liberal Cadiz Constitution required the Cortes’ approval for “treaties of offensive alliance, of subsidies, and special treaties of commerce,” as well as for any acts that alienated national property, imposed taxes, or admitted foreign troops into the kingdom.Footnote 101 Portugal's liberal 1822 constitution contained similar provisions.Footnote 102 The Cadiz Constitution also provided that the king “may not alienate, grant, or exchange any province, city, town, or village, however small, of Spanish territory,” implying that any such treaty would require a constitutional amendment.Footnote 103 More conservative early constitutions, like the 1815 Dutch constitution and the 1826 Portuguese constitution, left the monarch free to make most treaties but required legislative approval of territorial cessions.Footnote 104

A major turning point came with the 1831 Belgian constitution, which was the first in Europe to explicitly require legislative approval for treaties that modified domestic law.Footnote 105 Although there was apparently little debate over this provision, its framers chose to depart from a draft based on the 1815 Dutch constitution, apparently in order to protect Parliament's core prerogatives over law-making and the budget.Footnote 106 Many later constitutions followed the Belgian model, often combining similar language with peace treaties, territorial cessions, and other political treaties.Footnote 107

Thus, by the end of the nineteenth century, most Continental European countries—including major colonial powers—had adopted a similar model to regulate the treaty-making power. This model, explicitly enshrined in the constitution, required prior legislative approval for the ratification of a closed list of treaties, which virtually always included peace treaties, territorial cessions, and commercial treaties, and typically included additional items meant to protect the legislature's law-making and budgetary prerogatives.Footnote 108

Although they explicitly addressed treaty-making, nineteenth-century European constitutions did not make provision for the domestic legal status of treaties or CIL. This issue was largely left to courts, which generally considered that ratified treaties were directly applicable. By the end of century, courts in Belgium, France, Germany, Portugal, Spain, and Switzerland had so held.Footnote 109 These decisions were rarely explicit regarding their constitutional basis, though they sometimes reasoned that legislative approval implied that treaties should be treated as laws.Footnote 110 Few courts squarely addressed the question of the hierarchy of treaties and ordinary laws, but courts generally implied that they would give later inconsistent legislation preference over an earlier treaty, thus effectively giving them equal status.Footnote 111

Courts also regularly applied CIL rules without requiring implementing legislation, as evidenced by multiple cases from Belgium, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Portugal, Spain, and Switzerland.Footnote 112 These cases applied custom on sovereign and diplomatic immunities, but also the law of the sea, jurisdiction, the laws of war, extradition, recognition of states, and even the legality of royal marriage contracts.Footnote 113 Again, courts were rarely explicit about the legal basis for applying custom and usually did not discuss its place in the domestic hierarchy of norms. In general, they would not apply a customary norm in the face of a clearly inconsistent statute, regardless of which one was later in time. As a result, most courts effectively treated custom as directly applicable but with a hierarchical status inferior to ordinary domestic laws.Footnote 114

Thus, by the end of the nineteenth century, most European civil law jurisdictions had converged on a model that combined legislative approval of a closed but expanding list of treaties and direct effect of both treaties and CIL, giving the former status equal to statutes while the latter was considered inferior. This model would later diffuse through colonial lines to many civil law systems outside Europe.

2. Latin America

As Latin American countries gained independence in the early nineteenth century, they systematically adopted written republican constitutions. These constitutions, reportedly inspired both by European developments—especially Spain's liberal Cadiz Constitution—and by the U.S. Constitution,Footnote 115 almost invariably included provisions requiring legislative approval of treaties. For example, Peru's 1823 constitution provided that one of Congress's exclusive powers was “[t]o approve Treaties of Peace, and Conventions of every description, respecting foreign relations.”Footnote 116 Despite numerous constitutional changes in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, such provisions generally remained in force except in periods of civil war or dictatorship.

Some constitutions, usually those that later adopted federal systems, incorporated provisions inspired by the U.S. Supremacy Clause that explicitly gave ratified treaties domestic legal effect. Argentina's 1853 constitution, still in force today, explicitly made treaties “the supreme law of the Nation”Footnote 117 and granted the Supreme Court jurisdiction over cases “involving points to be decided by . . . foreign treaties.”Footnote 118 Mexico's 1857 constitution provided Federal tribunals with jurisdiction “to take cognizance of . . . civil or criminal cases that may arise under treaties with foreign powers.”Footnote 119 Colombia's 1858 and 1863 constitutions, as well as Brazil's 1891 constitution, likewise gave their respective Supreme Courts jurisdiction over cases involving treaties.Footnote 120 These provisions appear to have been primarily concerned with protecting the federal government's authority over foreign affairs against interference by states or provinces rather than with credibility.

In any event, Latin American courts generally gave direct effect to treaties regardless of whether such explicit provisions were found in the constitution. Thus, while Chile's early constitutions made no mention of the domestic legal status of treaties, courts applied them directly, as they did in Venezuela. Likewise, courts in Argentina, Colombia, Mexico, and Brazil appear to have considered treaties directly applicable even during periods when the constitution contained no such provisions. Although cases and commentary from that period are sparse, courts appear to have followed prevailing thought in civil law systems, including Spain and Portugal, under which treaties had direct effect on an equal footing with statutes. In some cases, the presence of specific clauses may have made a difference: the Brazilian Supreme Court, based on the 1891 constitution, appears to have been the first national court to explicitly hold treaties superior to domestic statutes.Footnote 121

Latin American constitutions did not typically contain any provisions governing the domestic legal status of CIL. Nevertheless, as in the case of treaties, and like courts in Europe, Latin American courts generally recognized that such norms were directly applicable but would yield to an inconsistent statute.Footnote 122 Late in the century, a handful of constitutional provisions on custom emerged. Colombia's 1863 constitution expressly provided: “The law of nations is part of the national legislation”—the first instance we found of a national constitution's expressly incorporating custom.Footnote 123 Venezuela's 1864 constitution contained a virtually identical provision, which reappeared in several subsequent constitutions but was gradually modified to clarify custom's inferior status relative to national laws.Footnote 124 These provisions, where they existed, do not appear to have modified, but simply confirmed, the domestic status of CIL.

By the end of the century, Latin American republics had thus converged on a model that combined features adopted from the U.S. Constitution with others similar to those prevailing in the civil law world. This model required legislative approval of treaties. Once ratified, treaties were directly applicable by national courts with a legal status equal to that of regular statutes. Unlike most European constitutions, Latin American constitutions generally required legislative approval of all treaties. CIL rules were considered directly applicable but inferior to domestic statutes.

3. The United Kingdom and Its Former Colonies

Unlike its continental European counterparts, the United Kingdom entered the nineteenth century with an established constitutional monarchy and a well-developed set of doctrines on treaty-making and the domestic status of international law. The sovereign, acting on the cabinet's advice, negotiated and concluded treaties without the need for parliamentary approval. Treaties had no domestic legal effect unless and until implemented by legislation; but there was a presumption that legislation should be interpreted to conform to obligations under ratified treaties. CIL rules were considered to form part of the common law. This approach remained constant throughout the century.

Toward the end of the century, several British settler colonies began to gradually acquire independence to conduct their foreign relations. Although their constitutions generally did not regulate treaty-making and the status of international law, they adopted the basic features of the British approach. For example, the preamble of Canada's 1867 constitution provided that it would be “similar in Principle to that of the United Kingdom.”Footnote 125 It vested executive power in a governor-general, the monarch's local representative, to be exercised by a government accountable to the Canadian parliament. It did not explicitly allocate the treaty-making power, and initially, foreign relations were conducted at the imperial level. But as that power was gradually transferred to the colony, it was exercised by the local executive as part of the royal prerogative. Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa adopted similar systems.

Likewise, local courts uniformly followed the British system as to the domestic status of treaties and custom. Treaties had no domestic legal effect unless and until implemented by statute. CIL norms, by contrast, were directly applicable as long as they did not conflict with statutes. The seamless adoption of this system sometimes rested on local laws providing that English statutes and common law rules remained in force unless modified. Even without these provisions, local courts routinely cited to English precedent. The Privy Council, which heard appeals from local courts even after independence, contributed to uniformity in canonical decisions that remain widely cited across the common law world.Footnote 126 Close educational ties with England and a practice of cross-citations may have further supported entrenchment of the British model.Footnote 127

The United States was the major exception to this systematic adoption of the British system by former British colonies that became independent during this period. The framers of the U.S. Constitution charted their own course that departed significantly from the British model. The United States, however, was not immune from British influence: U.S. courts followed English precedent in applying CIL rules directly.Footnote 128 Thus, the United States pioneered a hybrid model close to that being developed in continental Europe but with elements of the British tradition.

4. Conclusions

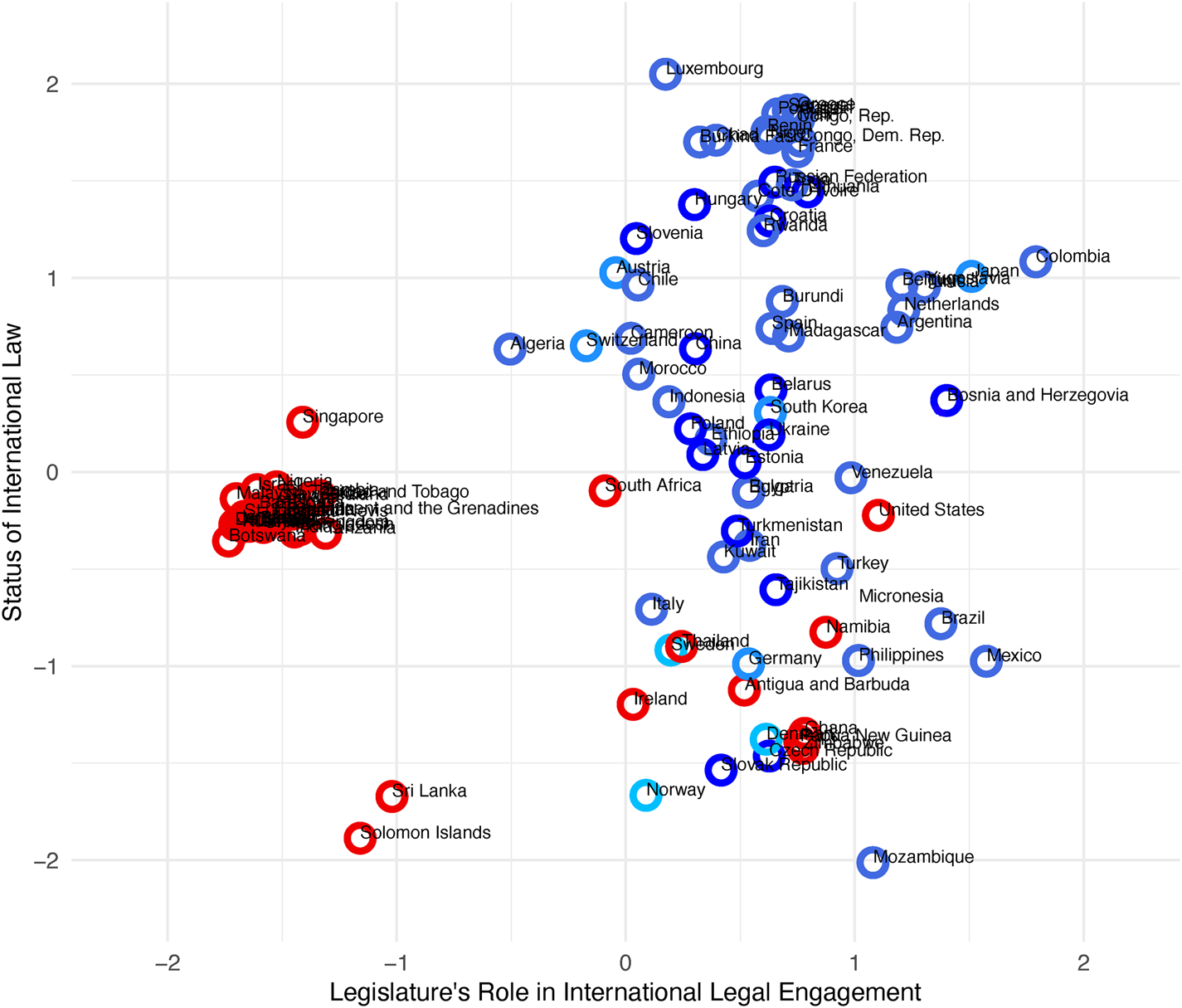

Figure 6 shows the policy point estimates for the countries in our dataset in 1900. It shows a cluster of continental European civil law countries that follow a similar model, with parliamentary approval of most treaties and direct effect of both treaties and CIL. A few countries that lacked parliamentary approval or did not give treaties direct effect appear at the left or below this cluster. Latin American countries tend to cluster to the right of the continental European cluster, reflecting their more comprehensive treaty approval requirements and similar doctrines on the domestic status of international law. Among common law countries, the United Kingdom is far to the left due to its lack of any legislative approval requirement for treaties, while the United States is close to Latin American countries. Portugal and Argentina, despite being monist, rank low on the second (vertical) dimension because, while they gave ratified treaties direct effect, they ranked them inferior to domestic law.

Figure 6. Policy Points in Two Dimensions, Color-Coded by Legal Origin, 1900

In designing rules on treaty-making, nineteenth-century constitutionalists appear to have been primarily concerned with protecting legislative prerogatives against the executive. In Europe, the United States, and Latin America, they achieved this end by requiring legislative approval of treaties, sometimes covering all treaties, sometimes only those that were most likely to impinge on legislative power. The adoption and expansion of constraints on treaty-making generally coincided with other constitutional reforms that limited executive power, expanded the franchise, and protected individual rights. In this respect, the evolution of foreign relations law is associated with the rise of constitutionalism and democracy in this period. In the United Kingdom and its colonies, democracy also progressed, but the well-established lack of direct effect of treaties mitigated separation of powers concerns.

While few nineteenth century constitutions (other than in federal systems) explicitly provided for the domestic status of treaties, their framers appear to have assumed that treaties would be given direct effect. Indeed, outside the British Empire and a few Northern European countries, this was the practice of most courts. Likewise, they applied international custom regardless of the absence of constitutional provisions. It seems likely that direct application of treaties and custom was initially rooted in the natural law tradition, which favored a monistic approach to law and did not insist on clear domestic sources of authority. With the rise of positivism, the status of international law would puzzle courts and scholars, but by then its direct application was well entrenched in practice.

Outside the United States, there is little evidence that credibility concerns influenced the adoption of rules giving direct effect to treaties, although this motivation may have been present in some Latin American countries. Courts, rather than constitution-makers, were the principal actors and appear to have acted based on prevailing legal ideas at the time rather than out of strategic considerations.

B. Wars, Crises, and Constitutional Experimentation (1900–1950)

The aftermath of World War I, the turbulent interwar period, and the post-World War II order brought several important developments. These included the rise of constitutional provisions giving treaties superiority over domestic statutes and providing for constitutional review of treaties. These developments did not fundamentally change pre-existing patterns, but rather set the stage for their worldwide diffusion of increasingly well-established models in the decolonization period.

First, the aftermath of World War I and the interwar period saw significant innovations in constitutional reception of CIL in Europe. Germany's Weimar Constitution Article 4 famously provided that “[t]he universally recognized rules of the Law of Nations are binding component parts of the German Imperial Law.”Footnote 129 Austria's post-war constitution, drafted by the famous legal theorist Hans Kelsen, contained almost identical language.Footnote 130 Other new constitutions referred to CIL but left its domestic legal status uncertain. Thus, Spain's 1931 Republican constitution provided that “[t]he Spanish State shall abide by the universal norms of international law, including them in its positive law.”Footnote 131 These provisions have been hailed as major innovations. Antonio Cassese, discussing Germany's 1919 constitution, enthused: “A new era opened . . . [f]or the first time in history a Constitution proclaimed State observance of customary international law.”Footnote 132

The practical impact of these provisions is open to question. CIL was already directly applicable by courts in Germany and Spain, as well as in Latin America.Footnote 133 It is unclear whether these provisions were meant to elevate its status and if so, if they succeeded.Footnote 134 The German and Austrian provisions triggered endless doctrinal disputes over what it meant for a norm to be “universally accepted.”Footnote 135 Many courts and scholars settled on the notion that, in order to be directly applicable, a CIL rule had to be accepted specifically by the country in question.Footnote 136 Meanwhile, the Spanish provision was read as a mere programmatic commitment.Footnote 137

After World War II, constitutional provisions on CIL reception became more common, appearing notably in the constitutions of Italy, Japan, and France.Footnote 138 Like the interwar provisions, these declarations appear to have had primarily symbolic value, as courts in these countries already applied CIL directly and the provisions did not purport to elevate their domestic legal status. The exception is Germany, whose post-war constitution was the first (and remains one of the few) to explicitly grant CIL norms superiority over domestic laws.Footnote 139

Second, treaty approval and reception rules did not change appreciably before World War II. Contrary to its framers’ proposal, the Weimar Constitution did not provide for treaty supremacy over domestic law; indeed, it did not expressly provide for treaty reception at all.Footnote 140 Neither did the 1920 Austrian constitution. Both appear to have left unchanged the pre-existing practice of giving ratified treaties direct effect, which also continued in other European countries. Spain's 1931 constitution did innovate in several respects, with provisions that appeared not only to confirm the direct effect of treaties but also to give them supralegislative status.Footnote 141 Civil war and the demise of Spain's short-lived republican regime, however, meant that these provisions had little practical impact.

By contrast, the post-World War II period saw several significant and lasting innovations. Provisions incorporating treaties in the domestic legal order appeared in constitutions that formerly were silent on the matter, including those of Japan and France.Footnote 142 The latter's 1946 constitution specifically granted treaties supralegislative status: “Diplomatic treaties duly ratified and published shall have the force of law even when they are contrary to internal French legislation; they shall require for their application no legislative acts other than those necessary to ensure their ratification.”Footnote 143 As discussed below, a similar provision would be incorporated in France's 1958 constitution and prove widely influential. While it would take several years for French courts to give these provisions full effect, they would, unlike Spain's 1931 provision, succeed in generating a consistent and robust domestic judicial practice of applying treaties over domestic legislation.Footnote 144

The 1958 French constitution also established for the first time a specific mechanism for contemporary constitutional review of treaties.Footnote 145 Article 54 provided:

If the Constitutional Council, the matter having been referred to it by the President of the Republic, by the Premier, or by the President of one or the other assembly, shall declare that an international commitment contains a clause contrary to the Constitution, the authorization to ratify or approve this commitment may be given only after amendment of the Constitution.Footnote 146

As a matter of principle, this provision affirmed that although treaties had supralegislative status, they must still yield to the constitution. As a practical level, it provided a mechanism to prevent ratification of unconstitutional treaties. Here too, it would take years for a meaningful practice of treaty review to emerge in France. As will be seen below, however, the provision was transplanted to numerous former French colonies, sowing the seeds for constitutional treaty review to emerge there.Footnote 147

Another innovation of the post-war era was the appearance of constitutional provisions that explicitly contemplated the formation of international organizations to which powers traditionally exercised at the national level could be delegated. The constitutions of France, Italy, and Germany contained such provisions, paving the way for the European communities.Footnote 148