INTRODUCTION

Shortly before concealed handguns were legally allowed at The University of Texas at Austin in 2016, Rosa A. Eberly wrote a counterpoint piece for Rhetoric Society Quarterly on the intertwined nature of public expression and gun violence in relation to the world of higher education, concluding that the questions of “how publics are characterized and how they function” have empirical and all-too-real consequences.Footnote 1 Noting that those in academia not only are affected by gun violence but have a responsibility to respond to the epidemic, Eberly appealed to professors – and their students – to “discuss, deliberate, and make rhetoric.” As vague as this may sound, the fact that Eberly's essay explicitly references the imminent arrival of Campus Carry at UT Austin may have served as a call to action, for that is indeed what professors and students did there: first discussing the new law, then organizing into activist groups (e.g. Gun-Free UT, Cocks Not Glocks, and Students Against Campus Carry), and finally creating rhetoric that gained their protests international attention.

This essay examines the use of rhetoric surrounding Campus Carry at UT Austin, exposing how competing frames of fear were strategically used by UT's academic community in the debate on the new policy. Attending to Eberly's question of how publics are characterized, which then bears on how they function, it demonstrates that such strategies were interwoven with the identities of the various factions, either for or against the law.Footnote 2 In multimodal forms of expression ranging from signs to online memes to teaching in class, fear appeared as a prominent trope by means of which the sides defined and defended their own positions while simultaneously delegitimizing their opponents. This mirrored similar dynamics at the national level, such as the success of grassroots gun-control organizations in building collective identity through such names as Everytown for Gun Safety and Moms Demand Action, or the framing of the “Other” in the National Rifle Association's construction of US gun culture.Footnote 3

The groups at UT Austin used fear-based rhetoric in very different ways. On one hand, activists attached special significance to their fear of guns in the classroom; it allowed them to find common cause and even served as the basis of their legal argument against Campus Carry. On the other, supporters of the law stigmatized the emotion, claiming it to be an invalid form of dialectic, while simultaneously (and contradictorily) leveraging it in their own messaging as a reason to be armed. In addition, fear was intentionally weaponized against students and professors. Accordingly, the fear-related rhetoric used by supporters of Campus Carry can be divided into two types: the “party line” used by local student groups connected to national pro-gun organizations and toxic polemics advanced by individuals.

In my discussion, I follow Lloyd Bitzer's pragmatic understanding of rhetoric as a means to provoke change, “a mode of altering reality … through the mediation of thought and action.”Footnote 4 An example is the traditionally pejorative interpretation of fear-based rhetoric as appealing to an audience's emotions to achieve a specific agenda, either by causing a perlocutionary effect (producing that emotion in the audience) or through an argumentum in terrorem with the promise of a negative consequence (e.g. “do this or else”). Certainly there is an established history of political and private organizations exploiting fear to rally support for their hawkish causes; examples in recent decades range from populist governments to the National Rifle Association.Footnote 5 In the situational context of UT Austin, however, a broader definition of the term is required: fear-based rhetoric also includes speech or acts that explicitly invoke or employ fear in characterizations of oneself or others. Employment of the emotion in a self-referential manner was intended to serve a strategic end, but it was also based on personal experiences. It is therefore important to note that in this case, fear was prevalent in the rhetoric because of the strength of the actual emotion, not merely political expediency.

THE “CHILLING EFFECT” AS RHETORICAL STRATEGY

A few weeks before the implementation of Campus Carry, three UT Austin professors filed a lawsuit against the university and Texas state to abrogate it. Central to their claims was that allowing “students to carry concealed guns in their classrooms chills their First Amendment rights to academic freedom.”Footnote 6 Mainstream media across the United States picked up the story, running with the expression “chilling effect” to describe the professors’ fear,Footnote 7 and the sound bite was adopted in scholarly parlance.Footnote 8 In turn, its definition was extended beyond the original scope of free speech to refer to the overall “feeling” of the larger campus environment. For instance, a UT graduate student argued, “I think that there is definitely a chilling effect to some extent, just having guns around here, and I think that it's helpful for people to know that they are not the only ones who feel that way.”Footnote 9 By identifying fear as something that could be experienced by anybody, the phrase “chilling effect” helped to empower individuals who perceived themselves as alone, indexing affect but also leveraging a mimetic force for their emotion to be shared. Adopted widely and easily reproduced (as seen in our interviews), the phrase also served as an affordance used to build community – and an activist movement. The Campus Carry opponents’ rhetorical adoption of fear, rather than dissociation from it, thus seemingly reflected an inversion of its negative connotation. As a strategy of appropriation, this rhetorical act rejected the passive-victim narrative, providing activists and opponents of Campus Carry with common ground and a means of agency in the lawsuit and interviews with the media.

Even so, there were signs that fear carried little, if any, import for the administration. A professor who interfaced with members of the Implementation Task Force, which had been appointed to form the procedures around the university's policy, felt that their attitude was patronizing. Their response was described as follows: “Well, I know there's a lot of fear right now, but you are going to find out it's all fine. Nothing terrible is going to happen. You'll calm down, don't worry. You are a little hysterical right now, but you'll be okay.”Footnote 10 The choice of language is noteworthy here, as the subtext of the word “hysterical” as a gendered insult suggests that women are more prone to excessive fear; this is all the more poignant, given the fact that anti-Campus Carry activists at UT Austin have predominantly been women. Another faculty member remarked on having the same experience, that the professors bringing the suit were “being described as hysterical women,” compared to strong males like Chancellor William McRaven, who also opposed the law but “is no wussy.”Footnote 11

Outside the administration, similar rhetoric was used by supporters of Campus Carry to paint the fear as much ado about nothing. One article published by the national organization Students for Concealed Carry (SCC) compared the “fear-driven hysteria” around guns at the university to the Salem witch trials.Footnote 12 Invoking the sociological concept of “moral panic,” defined as the “process of arousing social concern over an issue – usually the work of moral entrepreneurs … and the mass media,”Footnote 13 another article charged the “well-intentioned but misguided activists” with creating an atmosphere like the “Satanic panic” of the late twentieth century.Footnote 14 Similarly, the Texas branch of SCC referred to the university's faculty as a “cabal of fear-mongering professors.”Footnote 15 Aside from its inflammatory tone, such language is significant for its demonization of fear as an emotion for which people – not guns – are ultimately responsible.

BEYOND FEAR-APPEAL ARGUMENTS

Ironically, such discourse seems to ignore the legacy of fear-based rhetoric employed by pro-gun organizations themselves. The NRA has notoriously used insecurity to increase gun sales, invoking a range of doomsday scenarios for why one needs to be armed.Footnote 16 As a social force, especially when accentuated by alt-right media (e.g. Breitbart, InfoWars), this can be seen as paranoia that unseen forces – insert “liberals” or “globalists” here – are conspiring to take guns away from US citizens, stripping them of their Second Amendment rights. The NRA's CEO Wayne LaPierre argues, however, that the reason to be armed is not based on an emotional response but on the endemic insecurity of the world we live in: “It's not paranoia to buy a gun. It's survival.”Footnote 17 Thus, against charges of argumentum in terrorem rhetoric, which plays on a person's existing fears, the NRA frames its agenda as merely helping individuals to “anticipate confrontations where the government isn't there – or simply doesn't show up in time.”Footnote 18

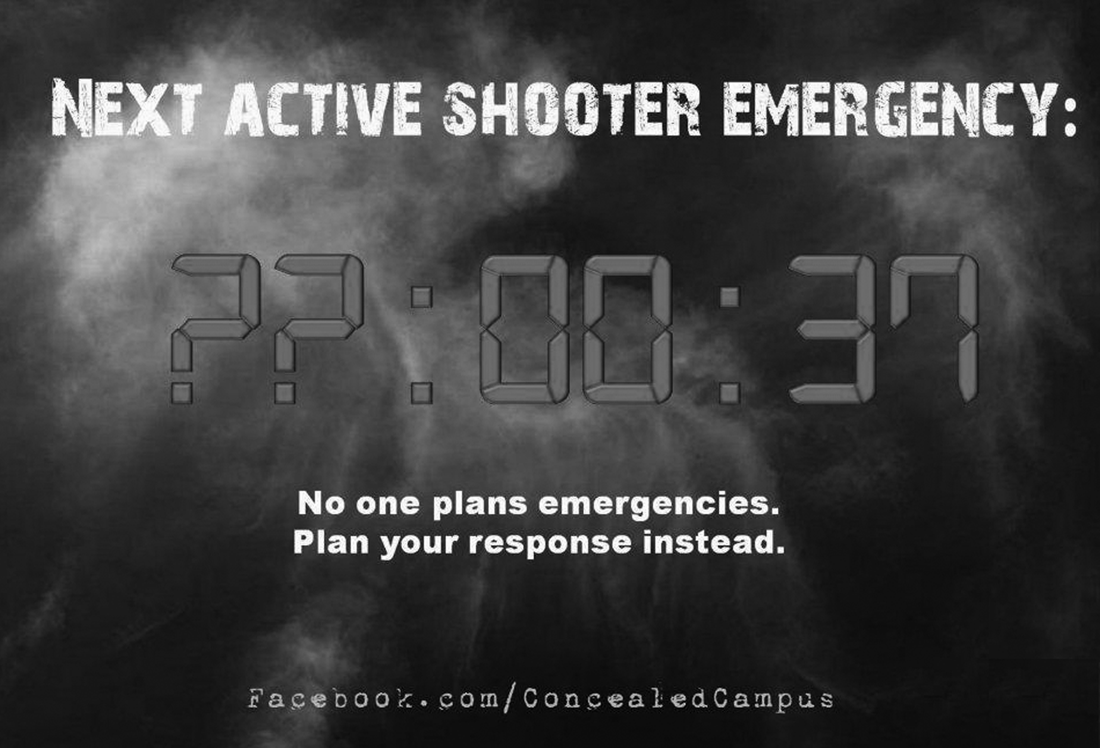

A similar tension was visible in messaging by student groups supporting Campus Carry. For example, a meme on the SCC website that warned of the potentiality of a deadly attack (see Figure 1) could be interpreted either as argumentum in terrorem or as straightforward paraenesis to drive preparedness in the event of a school shooting before the police arrive.Footnote 19

Figure 1. http://concealedcampus.org/images-slider/axiom-008.jpg (accessed 5 May 2019). Use permission granted by Students for Concealed Carry.

Nor should one necessarily correlate the logic of preparedness with fear. As focus shifted after the Cold War from the material world of bomb shelters to the human sphere of behavior, people are expected to be hardened, not sensitive, to shooter events.Footnote 20 Furthermore, while it could be argued that preparedness reflects a growing societal sense of ontological insecurity,Footnote 21 whatever the current bogeyman may be, gun rights groups fundamentally reject the connection between fear and security.

A press release by Texas Students for Concealed Carry provides such an example of the deconstruction of fear-based rhetoric. Its headline “Why Are Professors More Afraid of Guns Carried Legally than Illegally?”Footnote 22 frames licensed handgun carriers as not being a source of worry, but more importantly it entails a logic in which fear is not legitimate, as not based on reality. Together these lead to a conceptual turn in which the epistemological binary of one person's security being another person's insecurity is replaced with a problematization of the ontological veracity of fear itself. The SCC website says this much more simply: “Feeling safe or unsafe is not the same as being safe or unsafe.”Footnote 23 And their meme boils it down even further (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. http://concealedcampus.org/images-slider/axiom-002.jpg (accessed 5 May 2019). Use permission granted by Students for Concealed Carry.

After Campus Carry law passed and was implemented, the messaging by SCC also changed. Active argumentation shifted to occasional responses to opponents and, finally, complete silence. There was no longer any need to campaign or convince. Posts on the Facebook page of Texas Students for Concealed Carry on Campus ceased in early 2017,Footnote 24 and our research team's request to interview a representative of the group was met with a referral to an online archive of articles. The university practiced silence as well. The fact that it was much harder to find supporters of the law who were willing to speak to our research team, compared to vocal activists against it, underlined the sensitivity of the topic – and the importance of using confidential means of data collection (e.g. private interviews, an anonymous survey). Indeed, surrounded by a liberal majority at UT Austin, those who support Campus Carry can be reticent to engage in discussion about it. For example, an undergraduate supporter of the policy described the attitude of professors as “superior” when they spoke out against guns and how this “stifled the atmosphere.”Footnote 25 While this feeling cannot be equated to the chilling effect discussed above, it nonetheless signals the divide between those on opposing sides of the issue, which in turn reflects the impasse in the national discourse on guns.

Silence plays an inherent role in concealed carry. To speak of having a gun on one's person is to risk breaking the law and losing it. And yet guns can be considered a rhetorical tool in their own right. Operating outside formal speech acts, their twofold agency – potential and actualized – lies largely beyond words. A concealed weapon does not need to be drawn to be effective; such is the deterrent power of its potentiality. The inferred presence of the gun, as well as the fear it creates, looms large without anything needing to be spoken. When the gun comes out, the time for talking may well be over.

THE WEAPONIZATION OF FEAR

Taken as fear-based or not, the rhetoric used by national and local gun rights organizations tends to adhere to a certain line, with attention to being on the right side of the law. Yet the power imbalance inherent in carrying a gun can also extend to more toxic and illegal multimodal rhetorical acts by individual supporters of Campus Carry. Emboldened by the passing of the law, rogues acted outside sanctioned and institutional forms of discourse in ways that directly weaponized fear. Many antigun activists at UT Austin received threats – both tacit and explicit – of a disturbing and graphic nature. Instructors and students who belonged to activist groups against Campus Carry were repeatedly threatened and verbally assaulted by the general public, both online and directly. In one case, a Texas resident produced a video (“Never Met Her”) caricaturing a prominent Cocks Not Glocks student activist: victimized during a break-in, armed only with a sex toy and unable to protect herself, she is shot to death.Footnote 26 When this woman saw herself portrayed in this way on YouTube, she panicked. Reading it as a message for people to target her in real life, she “slinked to class the following day with aviators and a baseball cap on.”Footnote 27

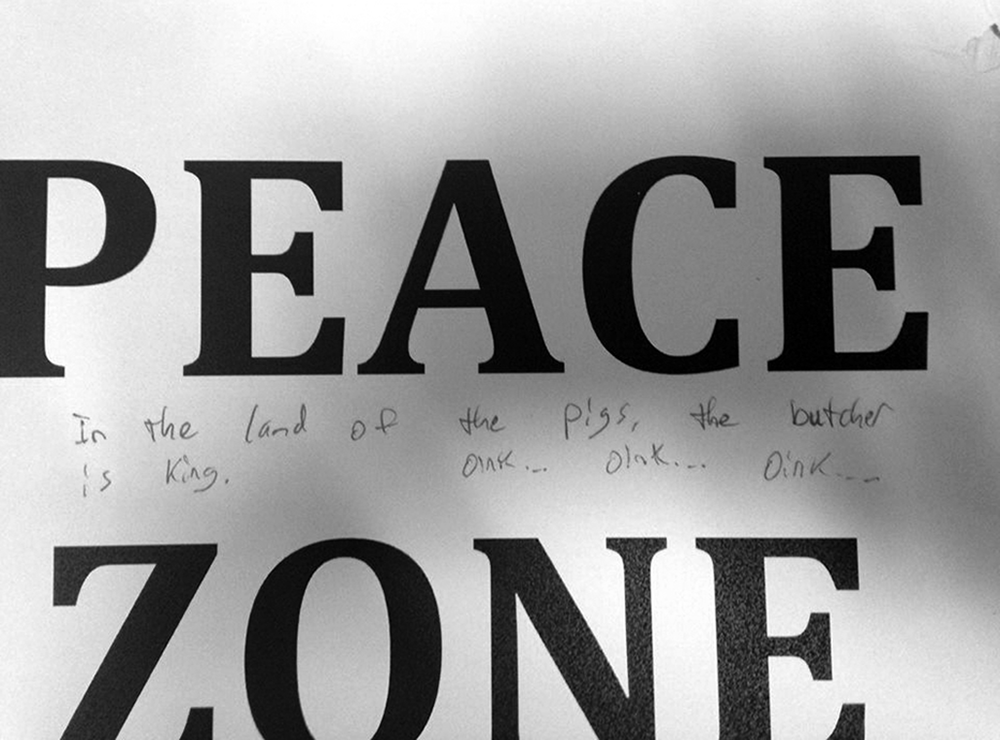

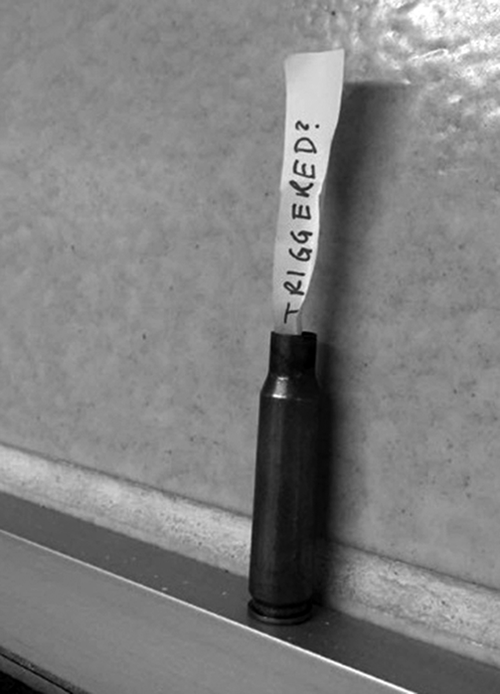

In another incident, in September 2016 a Gun-Free UT sign on a bulletin board outside the Department of Rhetoric and Writing in Parlin Hall was defaced by graffiti: “In the land of the pigs, the butcher is king. Oink … oink … oink …” (Figure 3).Footnote 28 Found nearby was an empty bullet casing, inside which was stuffed a tiny scrap of paper with a single word: “TRIGGERED?”Footnote 29 (see Figure 4).

Figure 3. Peace Zone sign. UT Austin. Photo credits: Casey Boyle.

Figure 4. “Triggered?” UT Austin. Photo credits: Casey Boyle.

Even if the multimodal rhetoric here was mere trolling of Campus Carry opponents, rather than a serious threat, both the physical object (the bullet shell) and the texts accompanying it represent potent signifiers of fear built on collectively understood perceptions of vulnerability by students and instructors. Especially given the mass shootings at schools in the United States, it is impossible to disregard the potential emotional impact of such an act, or the climate it creates. Entering social space, rhetorical actions have power to arouse and intensify very real fears in others. Imagine what effect this graffiti and bullet casing might have had on students who described themselves as already “very scared of guns here,” “terrified,” and experiencing “unmitigated repulsion and fear” around Campus Carry.Footnote 30

The fact that this happened outside the Department of Rhetoric and Writing also calls for a thick interpretation of the event. Kendall Gerdes's work on the rhetoric of sensitivity exposes how the word “TRIGGERED?” plays on a current debate in academia around “trigger warnings,” which are used with course materials to caution students that something they are about to read may be potentially disturbing. For some, trigger warnings are ridiculous, a signal “that ‘the gravest threat’ facing the university today is the sensitivity of students.”Footnote 31 In this view, too much attention is being paid to students’ feelings; in the context of Campus Carry, this extends to fear of guns in the classroom. For Gerdes, however, the incident reflects a type of intimidation which “presents a real threat to academic freedom,”Footnote 32 demonstrating that the classroom is no longer a “safe space” where students feel able to express their thoughts.Footnote 33 To the chilling effect of guns in the classroom, therefore, one can add a secondary impact on the learning environment caused by threats or attacks on one's feelings.

CONCLUSION

To return to Eberly's question of how publics function, the strategies of fear-based rhetoric employed at UT Austin – claiming fear, belittling fear, exploiting fear, deconstructing fear, and weaponizing fear – had varying degrees of success in relation to their goals. In all cases, fear itself carried a negative valence. Even if self-characterizations of being afraid galvanized community activism, there was a wish to move beyond the state of fear and the dysfunctionality it created in the classroom. Ultimately, however, the argument of the so-called “chilling effect” did not yield tangible results in terms of Campus Carry policy. First the district court for Texas and then the US Court of Appeals dismissed the plaintiffs’ claims as too subjective.Footnote 34 This lack of validation of the faculty's experiences underlined a broader dismissal of affect in the debate, as evidenced in the charges of hysteria (defined as an “exaggerated or uncontrollable” emotion). Of these two competing forms of fear-based rhetoric, the latter perhaps held more sway for those in power. Furthermore, the fact that Campus Carry was mandated by law made the rhetorical moves of its supporters largely irrelevant. Accordingly, they assumed a more silent and passive stance, which provided an alternative to the quagmire of argumentum in terrorem versus the logic of preparedness.

All this does not mean that the issue is going away, however. Even several years later, as the focus in the debate over Campus Carry at UT Austin appears to have shifted from fear to education, our interviews reveal that there remains a persistent force of community among its opponents. After gaining international recognition as champions in the gun debate, some students are continuing to protest, appearing in documentaries or speaking at national rallies like March for Our Lives. Rather than being deterred by the threats made against them, they appear empowered. The fear evoked in the student activist featured in the “Never Met Her” video did not prevent her from working on gun control as an intern in the office of a state senator or finishing her thesis on gun culture.Footnote 35 Similarly, professors have continued to discuss Campus Carry in their classes, and a vigil still held regularly by the Gun-Free UT group at the MLK statue on the East Mall serves to raise awareness for incoming students and passersby.

Nor would it be accurate to say that fear of guns at UT Austin has necessarily diminished. Aside from anecdotes shared by faculty, staff, and graduate students, three-quarters of undergraduates (78 percent) report not feeling safe with other students carrying concealed handguns in class.Footnote 36 Add to this the growing body of evidence that the presence of guns is indeed impacting education and the academic environment in multiple ways,Footnote 37 and one is left to conclude that an important direction for future research would be on the significance of fear in the classroom. Indeed, the actual reality of Campus Carry goes beyond mere rhetoric, representing what might instead be understood as a complex rhetorical situation affecting people's lives on a broader level and demanding critical discourse.Footnote 38